The Legend Of Prester John, King In The East, Explained

For more than two centuries from 1096 to around 1300, the Crusades dominated European history in the Middle Ages. Throughout, Christian forces attempted to overrun the Muslim population of the nations of the Middle East and, ultimately, take control of Jerusalem, a city of immense importance for both religions. During the 11th century, Jerusalem was controlled by a succession of Muslim governments: first, the Egyptians, who lost the city to the Seljuk Turks in 1071. However, the city also had a sizeable Christian population — it is believed that the so-called "Christian Church of the East" was at the time even larger than that in the West — whom the new rulers cracked down upon.

The Crusades were also motivated by the Byzantine Empire, the previous occupiers of Jerusalem who later saw their lands in Asia Minor slowly being overtaken by the Seljuk Turkish forces. The Byzantine Emperor called to Europe for Christian assistance, leading to the First Crusade known as the "People's Crusade" being ultimately defeated in Constantinople — now Istanbul — while another group made up of thousands of knights and foot soldiers managed to break into fortified Jerusalem in June 1099 and hold it for seven weeks before being annihilated. Eight more Crusades would be undertaken, all ultimately defeats for the Christians. And amid this carnage that permeated European consciousness for two centuries came a legendary figure: Prester John, a supposed powerful ally in the East who, it was said, might have tipped the scales of the conflict in Europe's favor.

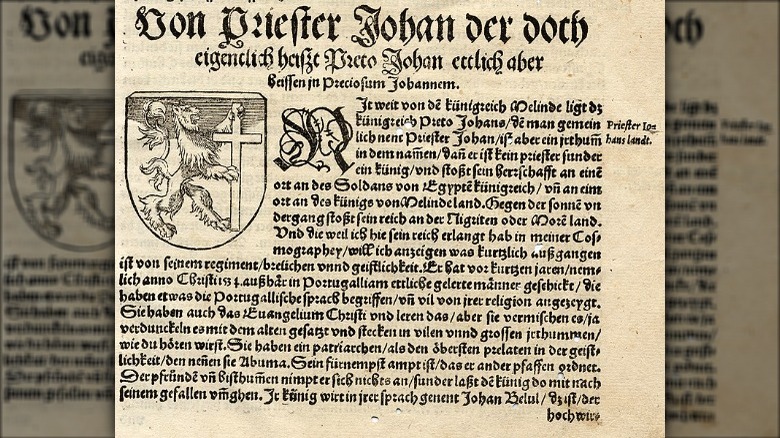

The letter from Prester John

In 1165, more than half a century after the first Crusaders were defeated at Constantinople and Jerusalem, a letter began circulating in Europe that would prove to be decisive in motivating a further campaign into the Middle East. The letter was filled with fantastical details, including the supposed existence of mythical beasts and strange two-headed humans, as well as a fountain of youth located somewhere beyond the reaches of the Western Church. But more importantly, the letter suggested that the Holy Roman Empire had a powerful hereto unknown ally in the letter-writer.

Apparently addressed to the Byzantine Empire, Manuel Comnenus – though other versions addressed to other European rulers also circulated — the letter claimed to be from a Christian King called Prester John, the ruler of a vast empire of 72 kingdoms in the East, which, while populated by monsters such as "vampires and dog-headed people" per Big Think, was a paradise linked to Christian utopia, with pure morals and zero crime. The immense wealth and powerful armies of John's lands offered hope to Europeans looking to return to the Holy Lands and reclaim the seat of Christianity. John offered to supply aid to European forces were they to make headway across the Tigris River against the occupying Muslims, a factor that motivated European leaders to return to the Holy Land thereafter.

[Featured image by tablespace.net via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

Prester John's inspiring victories

But Prester John's letter of 1165 wasn't the first time the legendary Priest-King from the East entered Christian consciousness in medieval Europe. Twenty years earlier, the Syrian bishop Hugo of Jabala made reference to a King John in his address to Pope Eugine III outlining the recent expansion of Muslim territories in the Middle East.

Hugo's report was generally bad news. However, he did suggest there was light at the end of the tunnel. He claimed that he had received reports of a Christian King from the East, specifically in the Mongolian Empire, who had laid to ruin a huge Muslim horde before losing contact with the West once again. The name John was evoked here and remained in the memory of European rulers looking to make a return to the Holy Lands following the defeats of the previous century.

Some historians now believe, however, that the Mongolian John of whom Hugo had spoken was a case of mistaken identity: that "John" was a derivative of "Kahn," specifically Kahn Ouang of the Keraites, whose forces had indeed engaged with Muslim opponents during that time and did count among their ranks a certain proportion of Christian soldiers. Later, reports of the battle would include fanciful details, such as the fact that the great Prester John had repelled the Muslim armies with copper statues that billowed smoke across the battlefield.

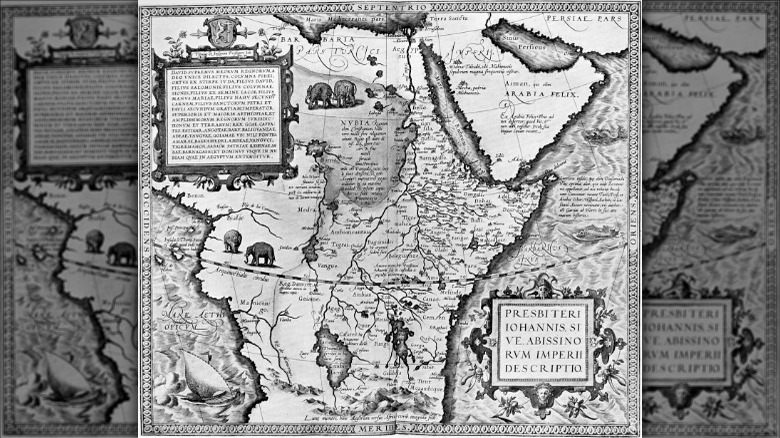

Where was Prester John?

As the crusades continued through the centuries, numerous European forces who found themselves far away from home did so with the overriding hope of encountering the legendary Prester John or his descendants on their travels, and making the decisive alliance between East and West that would see the crusades end in Europe's favor.

But where was Prester John? As the years passed, versions of the Prester John myth became numerous — prior to the advent of printing, letters were reproduced and circulated by hand, leading to additions and revisions which altered or exaggerated the details of the original letter – with followers speculating his lands could exist anywhere from India to Africa.

One of the most notable occasions in which the Prester John legend influenced the foreign policies of a European power occurred in 1520, when Portuguese explorers made their way to Ethiopia. Ethiopia had long been known as a Christian kingdom, having converted way back in the fourth century. Now, though — and although Prester John's letter was centuries old by this point — the kingdom the Portuguese encountered seemed to fulfill their vision of the legendary king's utopian land. Their encounter led to the Portuguese pursuing an alliance with the seemingly ideal Christians, who for their part were happy to indulge their arrivals' adulation. Though the Portuguese were a useful ally for the Ethiopians in a later territorial conflict, the relationship later broke down, and when Europe came to denounce the Ethiopian church it led to a bloody civil war that isolated the once revered country.

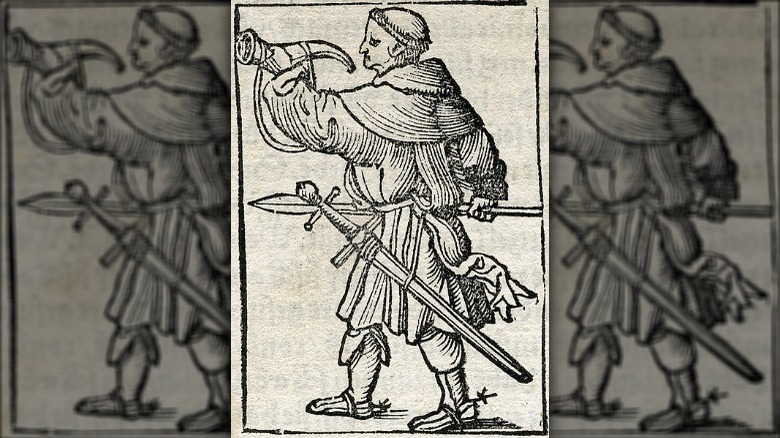

A Warrior Priest in the East

One of the most notable parts of the Prester John legend is that the man was a priest as well as a king. His legend was embellished with details suggesting that a connection with the lost Christian land would essentially neutralize the Middle East as a land of Christian paradise. Indeed, John's letter appeared to be a vision of it, with the supposed Priest-King claiming that his lands also contained such heavenly wonders as lands flowing with milk, an abundance of wealth and precious stones and treasures, and even the fabled Tower of Babel itself.

But the construction of John's empire in the letter and its later variants didn't exactly appeal to the Christian teaching of altruism as described in the New Testament. While John's letter claimed, for example, that there were no liars in his lands, it also details how those that do misspeak are shunned by society and ostracized, suggesting that such approaches also explain the absence of crime in John's lands. John notes also that there is zero tolerance for religious infidels, and while Jews and the Hindu caste of Brahman live on the land, they are "servants" and "ruled over" by John's Christian people respectively.

Prester John was thus a holy king evoking a sense of righteous Christian wrath — as historians have noted, the apparent presence of such a figure, even if his existence was unconfirmed, remained a decisive motivator for Crusaders throughout the centuries who were heading into the unknown.

[Featured image by tablespace.net via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

Did Prester John exist?

It is easy to see how a figure like Prester John could have fired up the imaginations of European Crusaders making the deadly decision to head East in search of a way to take possession of the Holy Land. However, it is almost universally accepted by most modern historians that Prester John was, if not a complete myth, then certainly a legend concocted from various pieces of information that had filtered through to Europe during the turbulent centuries of the Crusades.

In the early days of the Prester John legend, he was often described as the King of India, though the country we know the day was vaguely conceptualized in Europe at the time. As previously noted, it was also believed that Prester John may have been Mongolian, a fantastical rendering of the Nestorian Christian population that existed in the Mongol Empire. The empire in question was outrageously wealthy, and the reported Christian population may have led to the Mongol Empire being recast as Christian by word-of-mouth. In the 20th century, some historians argued that the vision of Prester John was indeed derived from a vision of Ethiopia, a land idealized in medieval Christian Europe, suggesting that the Portuguese explorers' instincts were correct. However, others have argued that John was based on no one figure in particular.

Instead, the main consensus goes that the letter from Prester John that emerged in 1165 was a forgery, and while historians have never definitively identified its author, it was certainly of Western origin. Whether a piece of intentional propaganda or not, it proved to be one of the most pivotal documents in medieval history.

[Featured image by The Bodleian Libraries, Oxford via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]