Rare Things You Probably Can't Do With Your Body

The human body is an absolute wonder of nature, capable of a great many interesting things that most of us take for granted. It possesses a state-of-the-art stereoscopic imaging system (your eyes), an olfactory system that can detect subtle variations in the composition of substances (your nose), and a complex system of organic hydraulics which can be trained to lift and support several times its own weight (your bones and musculature), among other fantastic features. It also has a lot of bells and whistles of the type that are not exactly essential to survival, but are still pretty cool; every time you whistle or snap your fingers, for example, you should probably take a moment to think about the first person to ever spontaneously do those things, then think to themselves, "Whoa."

Some folks, though, are sort of like really expensive luxury cars, in the sense that they come equipped while extra bells and whistles that are in no way necessary, but add a "wow" factor far beyond, say, flipping your eyelids inside out like that one weird kid in elementary school used to do. Most of these things have a genetic component, while some can (maybe) be learned — but all of them are pretty rare, so if you can do any of them, you can consider yourself special.

Spread your toes and bend your feet

Most peoples' feet are, well, pretty boring. Sure, they allow us to walk and all, but they don't really do much else. Roughly one in 13 people, though, have an extra feature added to their feet, as described in a study titled, "Brief communication: A Midtarsal (Midfoot) Break in the Human Foot," by Jeremy M. DeSilva and Simone V. Gill, a pair of Boston University scientists. What is a "midtarsal break," one might ask? Well, it means that the ligaments that support the joint between the heel and ball of your foot are softer and less rigid than normal, a gift from our ancient ancestors that allow some people to have more flexible feet than others. If you're able to spread your toes, or if your feet are otherwise... well, bendy, then you are probably one of those lucky people.

Obviously, for those ancestors, this would have been helpful for doing things like climbing trees — but as far as humans go, the jury is out on whether having bendy feet is beneficial. DeSilva, for instance, thinks that having this trait makes walking less efficient — but others, like UK researcher Robin Crompton, expressed a different view, opining that flexible feet could actually add stability in certain circumstances (via New Scientist). Until this is settled, you bendy-foot people can simply enjoy your ability to climb trees better than the rest of us with your weird, grippy toes.

Wiggle your ears

One could make the case that there is absolutely no benefit to being able to wiggle one's ears; one could make an equally strong case that this is malarkey, because somebody making a funny face while wiggling their ears is objectively hilarious. In any event, this appears to be an ability that is purely vestigial, being left over from the common ancestor of humans and primates, both of which can still display this ability. The rub: according to a study titled "Evidence for a vestigial pinna-orienting system in humans," it doesn't seem like the ability served any purpose in those ancestors, either. (With, of course, the possible exception of hilarity.)

Whether this ability is purely genetic or can be learned is somewhat unclear. While the study's authors seem to regard the ability as being purely genetic in nature, others are not so sure — like Dr. Kristin Woodward, an anesthesiologist who has independently researched quirky body phenomena, and who is probably a huge hit at parties. Speaking with Glamour, Dr. Woodward said, "The ability to wiggle the ears may be inherited, however it can also be learned with practice. It is thought that about 10-20 percent of the population has the ability." So, if you can't wiggle your ears but want to learn, just spend a little while every day trying really hard. Even if you fail, you'll probably look just as hilarious as if you had succeeded.

Bend your thumb backwards

The ability to bend your thumb way, way back is commonly referred to as "hitchhiker's thumb," although frequently hitching rides will not make your thumb any more bendy. The trait has been the subject of multiple scientific studies; one, published in 2012 under the impressively scholarly title "The Prevalence and Comparison of Bent Little Finger and Hitchhiker's Thumb in South-South Nigeria," found that it may be present in about one-third of the population. This, however, may be a slight oversimplification, for it has also been suggested that thumbs fall into more categories than simply "regular" and "extra-bendy."

In a series of papers titled "Myths of Human Genetics" by University of Delaware professor John H. McDonald, the notion that thumb type is binary was picked apart; the author pointed out glaring inconsistencies and the use of arbitrary criteria in previous studies, concluding that "most individuals [have] intermediate values, not the two distinct kinds of thumbs described in the myth." One could be forgiven for reaching their own conclusion: that professor McDonald had a great deal of time on his hands, and also two thumbs of decidedly medium bendiness.

Dislocate your shoulder voluntarily

Here's where things get a little bit wince-inducing. Remember, in the 1987 action-comedy classic "Lethal Weapon," how Mel Gibson's character could pop his arm right out of its socket at will? And then, he could pop it back in by dramatically and painfully slamming it up against the wall? Well, it turns out that some people can actually do that, and while it can certainly be painful, it's nowhere near as badass and dramatic. According to Raleigh Hand to Shoulder Center, these people suffer from a condition succinctly referred to as "shoulder instability" — and some of them, who are just as succinctly called "loose-jointed," can easily pop their shoulders in and out of their sockets with little or no pain at all.

It's unclear what percentage of the population are able to do this, and while the ability is often associated with trauma to the ligaments or muscles surrounding the shoulder socket, this is not always true. In 2012, a paper titled "Voluntary Anterior Dislocation of the Shoulder in a 10-Year-Old Child Treated Surgically" described such a case; the patient was able to pop the old right arm in and out of the front of the socket at will, with no pain, despite there being no history of injury to the area. The condition was rectified by way of surgery, so if you're able to do this, you can treat it that way, or you can just keep doing your party trick and freaking out your friends.

Be ambidextrous

We all know that the majority of people are right-handed, with a smaller minority being left-handed folks who are usually thought to be more weird and creative, although that is a misconception. Studies, such as one from 2020 titled "Genome-wide association study identifies 48 common genetic variants associated with handedness," have (as the title indicates) identified a strong genetic component associated with one's preference for one hand over the other, although it's not clear what, if any, purpose this preference serves. One interesting finding of that study, though, has to do with those odd outliers: ambidextrous people, who are neither left nor right-handed, but equally adept at using both.

According to ZME Science, about 90% of the general population is right-handed, about 10% are left-handed, and a sliver — less than 1% — are ambidextrous. This raises an interesting question. Some other studies, such as a 2009 examination titled "Genetic influences on handedness," have concluded that genetics are only about 25% responsible for your dominant hand preference, with the rest chalked up to upbringing and environmental factors. If this is true, however, it makes the mere existence of ambidextrous people a mystery — and as for that minute fraction of a fraction of the population that is capable of writing with both hands simultaneously, well, they may just be from another universe.

Touch your tongue to your nose

You have probably, at some point, encountered some wiseacre who says, "Hey, I can stick out my tongue and touch my nose!" They then proceed to stick out their tongue while touching their finger to the tip of their nose, then guffaw like they just totally pulled one over on you, you complete buffoon! Everyone knows that virtually nobody not named Gene Simmons can stick out their tongue that far — except that this is not the case. In fact, roughly ten percent of the general population can perform the maneuver known as "Gorlin's sign," much more than one might think — and if you happen to be afflicted with the condition known as Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a non-general segment of the population, chances are that it's easy.

According to the National LIbrary of Medicine, EDS is a genetic condition that affects the body's production of collagen, as well as the properties of that vital protein. The bodies of those suffering from it can exhibit a number of unusual properties, but it is characterized by a general... well, rubberiness of the joints, organs, and skin, and severe cases can cause serious problems ranging from fatigue and chronic pain to the wanton rupturing of arteries and organs. The ability to touch your tongue to your nose is sometimes indicative of the presence of this disorder — but usually, it just means that you're the lucky one in 10 who can win bar bets for the rest of your life.

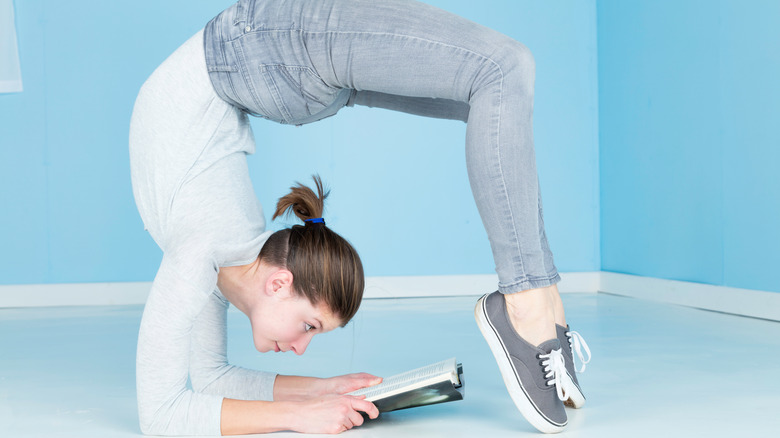

Be double-jointed

The phrase "double-jointed" is a misnomer, but just about everyone has known at least one person that can bend their joints, and often contort their bodies, in ways that must of us cannot. The medical term for this is "hyperflexibility," and those who suffer from Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome are extremely likely to exhibit it to a significant degree. For most hyperflexible folks, though, it's just a weird fact of life; due to genetics, their collagen is just brewed a little bit differently from most peoples', and as a result, they can bend and twist parts of their bodies in kind of freaky ways.

According to Dr. Michael Star of the Cleveland Clinic, hyperflexibility exists on a scale, with one person's hyperextension being another's leisurely stretch. "Everybody has a different level of flexibility. For example, dancers and gymnasts can bend over backward — and then there's me, who can't even touch the floor," he told the Clinic's website. "It's all on the mobility spectrum. Hypermobility is just at one end of it." About 20 percent of the population is considered to be hypermobile, and while the condition can lead to an increased risk of dislocations, that's not generally the case — and extreme cases can be treated with physical therapy, toughening up the muscles and ligaments that stabilize the joints.

Sneeze with your eyes open

Sneezing is one of those bodily functions that most people have a love-slash-hate relationship with. Sure, a good sneeze can feel satisfying — except when it's immediately followed by another one, and another, and another. Also, it sometimes seems like they come along at some pretty inopportune moments — while you're changing lanes in traffic, for example, or when you're about to field a fly ball. This is annoying because, as you might have noticed, it's virtually impossible to sneeze without closing your eyes — and yet, it can be done.

Nobody is exactly sure what the evolutionary purpose is behind your eyelids automatically slamming shut when you sneeze, but according to allergist Dr. Purvi Parikh, sneezing — and the accompanying eye closure — is what's known as an "autonomic reflex." Other things that fall into this category include swallowing and breathing — in other words, these are bodily functions which are very difficult to override. Speaking with Well and Good, Dr. Parikh explained that with practice, one can learn to keep their eyes open while sneezing — it's just really tough to do. If you're prone to allergy attacks and find yourself in heavy traffic often, though, it may not be a bad idea to give it a shot.

Contort your tongue into weird shapes

The ability to fold your tongue lengthwise, while not universal, is a fairly common trait. As described by Dr. John H. McDonald in his "Myths of Human Genetics" series, this ability has in years past been used in classes as sort of a basic introduction to genetics — but, says Dr. McDonald, this is a fallacy. While the trait may have a genetic component, the prevalence of "rolling" children born to "non-rolling" parents, and vice-versa, suggests that it's a bit more complicated than whether or not one has a tongue-rolling gene. Also, upwards of two-thirds of the population can do it — and it has been demonstrated that it's relatively easy to learn.

There are, however, weird tongue maneuvers that are quite a bit less common, according to a 2020 study titled "Five Specific Tongue Movements in a Healthy Population" conducted in the Netherlands. It was found that, while 83 percent of the study's participants could fold their tongue lengthwise, far fewer could fold it width-wise (about 27 percent), twist it to the left or right (around 35 percent), or make that cloverleaf shape with it like your really weird buddy Dave (roughly 15 percent). When it came to the physiological reasons behind these abilities, though, the study drew a big old blank.

Raise one eyebrow

Cocking one eyebrow is a great choice for when you want to look quizzical, express possibly ironic interest in something, express incredulity, or look like Mr. Spock. Some can do it effortlessly, and some don't seem to be able to do it at all — and this is another "skill" for which the genetic component, if any, is not known. There is one study, however, that suggests a correlation between the ability to raise one eyebrow independently of the other and another, completely different useless skill.

The 1995 study, titled "Asymmetries in ear movements and eyebrow raising in men and women and right- and left-handers," examined the relationships between the abilities to raise one eyebrow and wiggle one or more ears, looking for any increased instances of either among right handers, left handers, and ambidextrous people. It found none — but it did conclude that there were "significant contingency correlations" between single-brow-raising and ear wiggling. It stands to reason that this may have something to do with certain qualities of the facial muscles in people that can cock a brow, wiggle an ear, or both — but if that's true, nobody has been able to ascertain what those qualities are. Yet. Don't count science out on this one.

Make your ears rumble

The following sentence will likely strike you as either totally weird or completely obvious. There are people who, upon scrunching the muscles of their face a certain way, produce a dull roaring sound in their ears. (It should be noted that the sound can be heard only by them, not by everyone, because that would definitely be totally weird.) In 2020, a tweet by science guy Massimo describing this effect went stupidly viral, with the comments largely falling into two camps along the lines of either "I had no idea" or "I thought everybody could do this." Those that can, as it turns out, have the unique ability to voluntarily contract a set of muscles that others cannot: the tensor tympani muscle, the largest muscle residing in the middle ear.

A 2013 paper titled "Voluntary contraction of the tensor tympani muscle and its audiometric effects" noted that despite its size and prominence, the exact function of this muscle is unknown — although it does appear to dampen the totally gross sounds of chewing when you're eating. The subject described in the paper reported a form of tinnitus, only instead of ringing, he would hear roaring in his ears when flexing the muscles of his mug a certain way. Upon examination, it was found that he was able to voluntarily contract both tensor tympani muscles at once, resulting in the loss of lower frequencies while doing so. The paper doesn't state whether the doctor simply told him to stop screwing up his face like that, but it's fun to imagine this to be the case.

Gleek

If you don't know what gleeking is, then congratulations on skipping middle school. For those of you who did attend, you'll recall that one weird kid named Tony (it was always Tony for some reason) who had perfected the skill of, seemingly effortlessly, firing tiny balls of spit out of his open mouth, landing them with alarming accuracy wherever he pleased, which was usually around the vicinity of your eye. You never knew what to call it, until you heard that kid Spencer (there was also always a Spencer) protest, "Tony! Stop gleeking on me or I'll tell!" But he never told, and Tony kept gleeking away at him, you, and everyone else.

This ability is, believe it or not, one that can be learned. There are, you see, glands called "sublingual glands" on the underside of your tongue that produce saliva, which builds up in there in tiny amounts. If you learn to contract the muscles around this gland — and you can, anyone can with enough practice — then you, too, can gleek. Dentist Mark S. Wolff gave a few helpful tips to Health: First, try eating something sour, which helps build up the saliva. Stick out your tongue and lift it, then curl the tip behind your front teeth. Then, tense your tongue muscles, and voila! Gleek city. Of course, Tony would have told you all of this years ago, if you'd just asked. All the gleeking was just his weird way of trying to make friends.