The Untold Truth Of Thanksgiving

At its best, Thanksgiving is a reminder of how often people take life for granted. Families congregate to clog their arteries with entirely too much food and reflect on how lucky they are to do so. At its most awkward, the holiday is a reminder of why people feel grateful not to see their relatives every day. But behind the cavalcade of calories and potential shouting matches is a rich and sometimes heart-wrenching history. There are moments of privation, excess, and oddness that many people might not have heard of, let alone contemplated while cleaning their plates.

Below you'll find cannibals, animals, presidents, and a pirate. You'll find laughter, sorrow, and false beliefs in need of myth-busting –- because a day devoted to overeating should be seasoned by food for thought. Not everything you find will make you smile, but hopefully you'll be thankful that you read it. Here's the untold truth of Thanksgiving.

America's cannibal Thanksgiving

It doesn't take a rocket scientist to tell you the Pilgrims didn't invent Thanksgiving because that's a historian's job. Plus, according to the Library of Congress, Native Americans had ceremonies for giving thanks long before the fabled 1621 feast in Plymouth that is often heralded as the basis for Thanksgiving. But even if we focus exclusively on the roots of the U.S. tradition, Plymouth seems like an arbitrary starting point because settlers in Jamestown, Virginia, had a food-related thanksgiving prayer service in 1610. So why does that earlier event get overlooked?

Jamestown curator Merry Outlaw blamed the omission of the 1610 ceremony on its ghastly backstory. Jamestown's colonists -– well, what was left of them –- had just survived the Starving Time by the skin of their teeth. Amid a bitter winter in which 80 percent of Jamestown's 300 settlers perished, the increasingly desperate colonists resorted to eating rats, horses, shoe leather, and ultimately human flesh. The famished few who lived were saved by British ships bearing food.

In 1619 Virginia had another thanksgiving service when Starving Time survivor Captain John Woodlief journeyed to the Berkley settlement on business. This second, less people-flavored celebration is the one Virginians tend to recognize as the "first" American Thanksgiving. Interestingly, JFK seemed to acknowledge this fact in a 1963 speech. But almost nobody credits poor, ignored Jamestown because some parts of history are hard to stomach, especially when those parts belong to people.

The beheading of 1623

Historical events are like faces: They sometimes get made up to conceal blemishes. America's Thanksgiving narrative is caked with makeup. The typical depiction, as summarized by Time, is a chummy three-day feast attended by at least 50 Pilgrims and 90 Native Americans in 1621 to commemorate a successful harvest made possible by helpful Natives. Peace between the groups allegedly lasted 10 years before an influx of European settlers brought a devastating plague and sowed the seeds of all-out war. In reality, there was more to the harmony than a harvest, and the violence erupted after two years.

Dr. Jack Dempsey, an expert in early American and Native American history, explained that the Pilgrims and Native Americans made a Thanksgiving treaty against a backdrop of dire conditions. In 1616 an epidemic annihilated tens of thousands of Native Americans along the Northeast coast, and a previously established peace with Europeans was plagued by conflict. The Pilgrims, meanwhile, were unprepared to brave the bitter winters of Plymouth. So the two groups agreed to get along out of desperation.

The Pilgrims soon grew paranoid and suspected the Native Americans planned to attack them. Captain Myles Standish preempted the suspected plot in 1623 by inviting the Massachusett tribe leader Wituwamat and several other Native men to a feast. It was a trap. Standish and his companions slaughtered their guests, beheaded Wituwamat, and mounted his head on the fort/church at Plymouth.

Thanksgiving used to be considered an abolitionist holiday

Thanksgiving forces families to confront the reality that sharing DNA doesn't mean sharing beliefs. Eventually holiday pleasantries will give way to squabbling over politics, religion, or which relative is a doody head. In such moments it might feel as if your family will split in two. But just remember: Your Uncle Sam got through worse. All it took was a bunch of cannons and bayonets.

Long before your hypothetical relatives were around to fling insults, Thanksgiving became a divisive issue in the lead-up to the Civil War. Not yet a national holiday, it was primarily celebrated in New England. This was essentially a geographical accident. New England was affiliated with the Pilgrims, and as detailed by Atlas Obscura, Thanksgiving staples like pumpkin pie were easier to prepare there because the ingredients were easier to grow there. However, the region's abolitionist leanings rubbed Southerners the wrong way.

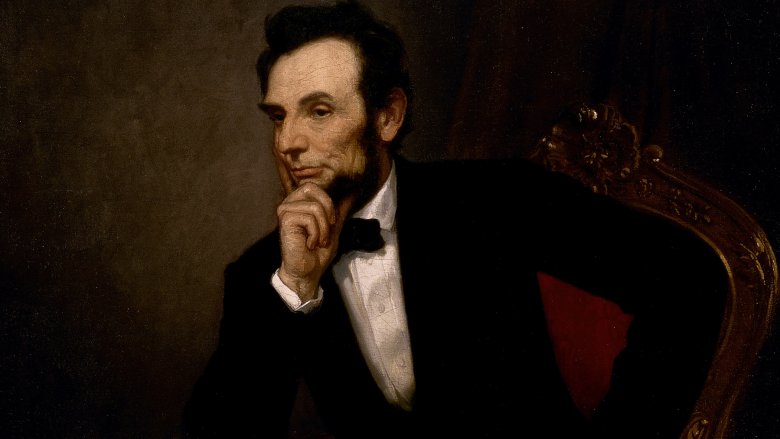

Several pro-slavery states embraced Thanksgiving during the 1840s, per the LA Times, but by the 1850s tensions over slavery had intensified and Thanksgiving had grown in popularity across Northern states. As a result places like Virginia refused to celebrate it. Multiple newspapers slammed the so-called "abolitionist" holiday, with one calling it "little more than an occasion for indulgence in dissipation at the cost of character, health and slenderly provided purses." In 1863 President Lincoln called for an end to the quarreling and war and declared Thanksgiving a national celebration.

Canadians have an English pirate to thank for their Thanksgiving

Our northern neighbor, Canada, has its own national day of gratitude. Like the Yankee version, it includes family get-togethers and scrumptious turkey corpses, so it might seem like a copycat, or as the Canadians might call it, a mimic-moose. But according to Time, one reason Canadians wanted their own Thanksgiving was that they were grateful for not being Americans, who had ripped themselves asunder during the Civil War. A much cooler distinction is that Canada's holiday is tied to an English pirate.

That sea plunderer was Martin Frobisher, who became known for "preying on French trading vessels" in Guinea and searching for treasure, per PBS. Frobisher also made a name for himself as an explorer. In 1578, 43 years before the Pilgrims became famous for eating, he and his crew dropped anchor Newfoundland. Relieved that they didn't die, the men commemorated the moment with a Thanksgiving ceremony. It marked the first known European Thanksgiving in North America, per the Canadian Encyclopedia. Frobisher eventually died fighting the Spanish, but his journey lived on in Canadian lore. The country officially adopted Thanksgiving as an annual celebration in 1879.

The tragic sports disaster that time forgot

Regardless of whether you eat ham on Turkey Day, you can still feast your eyes on pigskin, thanks to football. Watching people get tackle-happy on thankful Thursday is a time-honored U.S. tradition that's almost as old as the holiday itself. According to History, people started getting thankful on the gridiron a few years after Thanksgiving became a national holiday in 1863. Unfortunately, when you do anything for that long, something's bound to go wrong.

In the 1890s Stanford University and UC Berkeley developed a spirited gridiron rivalry that the schools revisited every Thanksgiving. Per Stanford Magazine, the competitions were exclusively held in San Francisco and attracted ginormous crowds. The spectators sometimes outnumbered the seats by a large margin, and some resorted to dangerous tactics to get a view of the game. This led to a partial stadium collapse in 1897 when an estimated 15,000 wedged their bodies into a space made for 10,000, with many watching from atop the roofing. In 1900 things turned deadly.

As in previous years, droves of fans came out to watch the 1900 Thanksgiving scrum between Stanford and Berkeley. Not everyone could afford the $1 tickets, so hundreds of fans mounted the ramshackle roof of a nearby glassworks. The structure shattered under the weight, and more than 20 spectators -– primarily children –- perished. It was the worst disaster in American sports history.

For two years the U.S. had two Thanksgivings

Humans are creatures of habit. Sometimes those habits are bad, but other times they're things like celebrating Thanksgiving on the fourth Thursday of November in the U.S. or the second Monday of October in Canada. However, people weren't always picky about when they overdosed on pie and poultry. AL.com explained that the U.S. and Canada inherited the practice of giving thanks on designated days from England, which usually didn't reserve specific dates for such occasions. And according to the U.S. National Archives, commanders-in-chief used to issue Thanksgiving Proclamations for different days and months of the year.

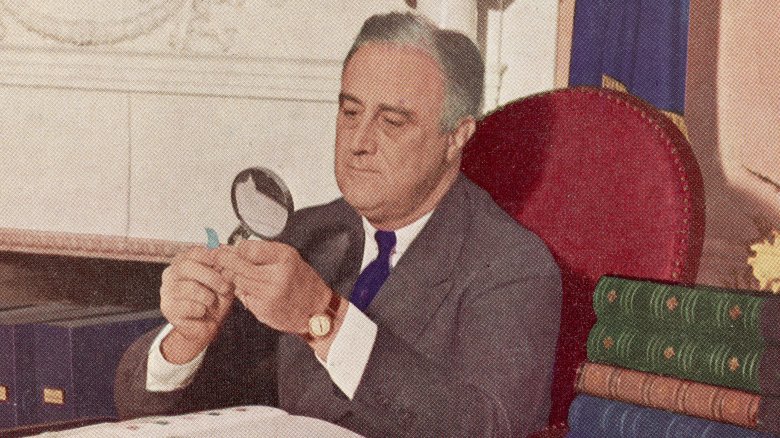

When Abe Lincoln finally made an honest holiday out of Thanksgiving, he declared that America would celebrate it on the last Thursday of November. Citizens got used to this and became set in their ways. So when FDR moved Turkey Day to different week, numerous U.S. states flipped the bird.

The holiday rift occurred in 1939, a year when Thanksgiving fell on the last day of November. Retailers wanted more time to peddle goods before Christmas, so FDR told people to be grateful on the third Thursday. Thirty-two states followed suit, another 16 said nope, and Texas and Colorado celebrated Thanksgiving two weeks in a row. Some declared the new date an imposter, calling it "Franksgiving," after FDR. This went on for two years, during which obesity rates probably quadrupled in Texas and Colorado.

Thanksgiving used to dress like Halloween

Kids love playing dress-up, which is partly why Halloween is so popular. So it's only fitting that when Thanksgiving was a fledgling national holiday, it dressed up as Halloween. From the late 19th century through the first half of the 20th century, kids went out in costumes on Turkey Day and did something akin to trick-or-treating. An 1897 LA Times piece cited by NPR called it "the busiest time of the year for the manufacturers of and dealers in masks and false faces." (Above is a "masking" photo from a Thanksgiving in the 1910s.)

Much like the fright nights of today, the Thanksgivings of yesteryear saw people masquerade as well-known politicians, animals, and crass stereotypes of foreigners and poor people. In New York, Thanksgiving also went by Ragamuffin Day because so many dressed as beggars and asked people on the street for goodies. Usually they were greeted with apples, candy, or pennies. Pennies sound like the crappiest treat ever, but they were actually worth something back then.

As Thanksgiving matured, adults decided it was time for the holiday to grow up. In 1930 a New York school superintendent argued that "modernity is incompatible" with costumed kids asking adults for stuff on a holiday with "giving" in its name. Thankfully, the movie Miracle on 34th Street came out in 1947, and Thanksgiving started behaving more like Christmas.

Our image of Thanksgiving dinner partly came from wartime propaganda

If a picture says a thousand words, you should probably ignore all of them because pictures are filthy liars. Take Norman Rockwell's 1943 painting Freedom from Want (above), for instance. It shows an unnaturally happy family at a table as the man and woman of the house make love to a succulent turkey with their eyes. That image captures what many modern Americans view as an ideal Thanksgiving dinner, but as Smithsonian Magazine noted, Rockwell's work wasn't art imitating life; it was art trying to sell war bonds.

Freedom from Want was part of the "Four Freedoms" series, which aimed to drum up support for World War II. To that end, Rockwell recruited his neighbors in Vermont to pose for warm depictions of home life that tugged at people's heartstrings and, by extension, their purse strings. But up to that point in U.S. history, families gathering for home-cooked dinners wasn't a widespread Thanksgiving tradition. Instead, those who could afford it dined at posh restaurants or on cruise ships.

Peggy Baker, a librarian at the Pilgrim Hall Museum, described some of the sumptuous scrumptiousness people were thankful to eat. An 1894 menu included a four-course meal with such appetizers as oyster crabs in béarnaise sauce, entrees that included Peking duck with onions and squash, and desserts like almond cake with maple frosting. Eating at home became more common once the Great Depression hit.

For many Native Americans, Thanksgiving is a day of mourning

For many Americans, Thanksgiving is about appreciating the present and honoring a mythical past. Their day of grateful gluttony pays vague homage to bygone figures from a 17th-century feast steeped in wholesome imagery and wholesale revisionism. But others are haunted by the ghost of Thanksgiving past and atrocities that followed. As Smithsonian Magazine recounted, the peaceful Plymouth meal that we often associate with Thanksgiving was the precursor to decades of slavery, sickness, and genocide. Approximately 300,000 Native Americans in New England met violent ends at the hands of Europeans, and even more were displaced.

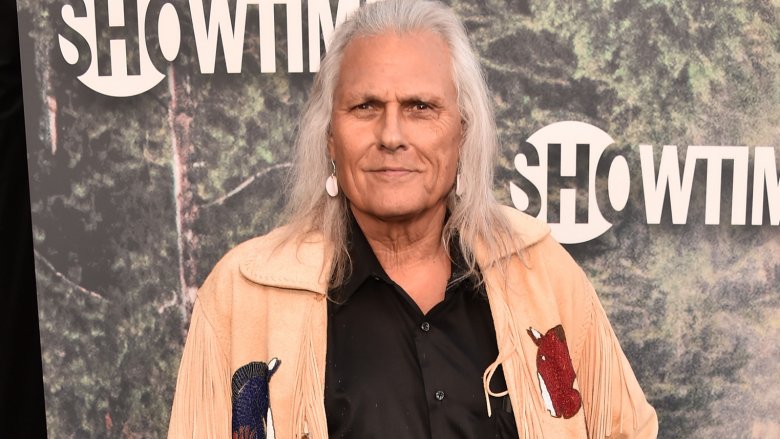

Understandably, many Native Americans know Thanksgiving not as a holiday, but as the Day of Mourning, or Unthanksgiving Day. Native American actor Michael Horse (above) of Twin Peaks fame told Newsweek, "It's about reflecting, remembering, and celebrating that we are still here and our culture still survives." Instead of weighing down their tables with fattening food, Horse and others attend a ceremony in remembrance of a three-year occupation of Alcatraz Island aimed at turning it and its famous prison into a Native American cultural center.

Unthanksgiving Day serves as a stark example of how differently history is experienced across groups. For those who ended up on top, the past is like a frozen image, something we can examine dispassionately. But for those who suffered terribly and still feel the effects, the past never really stopped happening.

A sitting president nailed a live turkey to a table

The White House tradition of pardoning donated turkeys officially started in 1989 with President George H.W. Bush, but the idea predates his administration. In fact, when JFK showed mercy to a turkey in 1963, the Washington Post called it a "pardon." Obviously, that wording is a bit tongue-in-beak, but it makes no sense because turkeys always follow the laws of nature by being delicious, which technically makes them the opposite of criminals. Besides, as NPR pointed out, for a long time Americans felt that turkeys served their country by being served for dinner. According to a 1911 essay, "the patriotic turkey dies for his country on Thanksgiving day." By refusing to eat them, we turn them into traitors.

Pardoned turkeys aren't just un-American; they're morbidly obese. That's because people don't wait until the birds are dead to stuff them. Humans like their Thanksgiving poultry to be extra plump so we can get extra plump eating it. At least two of the butterballs rescued from President Obama's dinner table were eight times bigger than the average wild turkey, so they probably died prematurely.

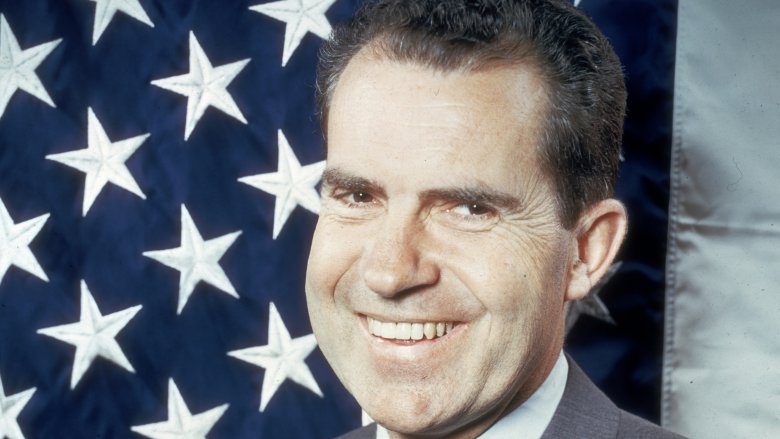

Presenting live turkeys at the White House can also get pretty morbid. Vietnam War villain Richard Nixon (who received an actual presidential pardon after Watergate) lived up to his nickname, "Tricky Dick," when he had a turkey's feet nailed to a table in order to restrain it.

The term 'Black Friday' used to discourage shopping

It seems counterintuitive to go shopping on a day called Black Friday. After all, "black" days in history typically coincide with negative events like economic panics. Granted, you might feel panic on Black Friday when your pants no longer fit because you ate your weight in green bean casserole the night before. But compare that with the Great Depression, which had a Black Thursday, Black Monday, and Black Tuesday that gobbled up America's greenbacks, and a Black Sunday that blotted out the sky. So why is Friday the black sheep?

It all boils down to timing and marketing. Before it meant "the day after we gained 30 pounds," "Black Friday" described a financial catastrophe. Per Business Insider, in 1869 a pair of investors tanked the stock market by manipulating the price of gold. Snopes reports that some employers called it "Black Friday" in the '50s because of how many employees called in sick, while retail scholar Michael Lisicky says Philadelphia police started using "Black Friday" to describe the awful day after Thanksgiving in 1966.

In the City of Brotherly Love, cops despised the annual parade of traffic and shoplifters. In fact, the Black Friday label originally discouraged some shoppers from coming out because it sounded so ominous. However, retail executive Peter Strawbridge is credited with creating an alternative narrative about businesses profits being in the black.