What 19th-Century Circus Life Was Really Like

The arrival of the circus in a small town was among the most exciting events in the lives of rural Americans. The chance to see wild animals and trained performers doing amazing stunts in colorful tents, covering enough ground to be its own village, was a once-in-a-lifetime experience for the massive crowds that flocked to the circus. For the hundreds of people who lived, worked, and performed in circuses, though, these incredible sights were a part of everyday life.

The 19th century was a time of real change in the United States, and the circus was changing with it. The massive technological advances of the 1800s allowed the shows to grow larger than ever and travel widely. This era gave rise to some of history's most famous circuses, such as Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, and provided rare opportunities for people to find their place in the show, travel the country, and possibly achieve fame and fortune. However, life could also be extremely difficult and even dangerous for those who made their living in the 19th-century circus.

You might start out as an apprentice

One way to begin a career in the circus was to learn from other performers as an apprentice. This could be an extremely hard life, as many apprentices began working as children or teenagers. As described in "The American Circus," there were many reasons why a child might find themselves apprenticed in the circus, but a common one was that they had no family to take care of them. These vulnerable children and teens were welcome additions to many shows, because they were expected to work for their place in the circus. Depending on what kind of labor they were required to do, this could be a highly dangerous position, and apprentices had very little control over their own lives or how they were treated. Many left before their apprenticeships were complete.

However, for apprentices who did manage to secure a good position and receive valuable training, there were great opportunities. Many performed in the show while they were still apprentices, and some of the 19th century's greatest performers began their careers this way. And it wasn't just performers who started as apprentices; even William C. Coup — who, along with partner Dan Castello, would pioneer the circus train and join forces with P.T. Barnum — began his life in the circus with an apprenticeship.

There were many different specialities to choose from

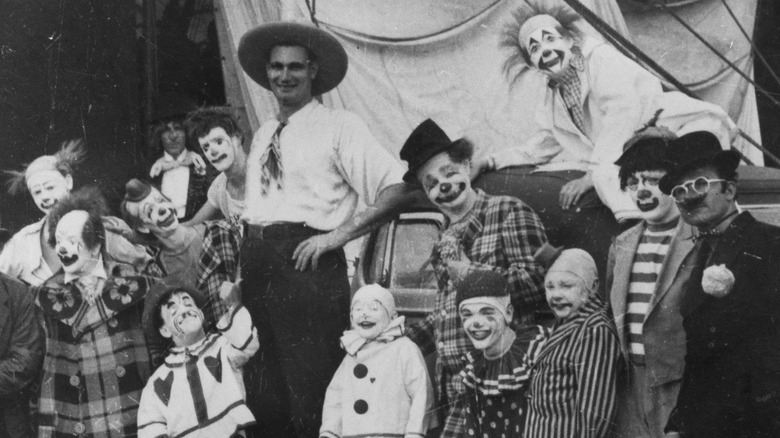

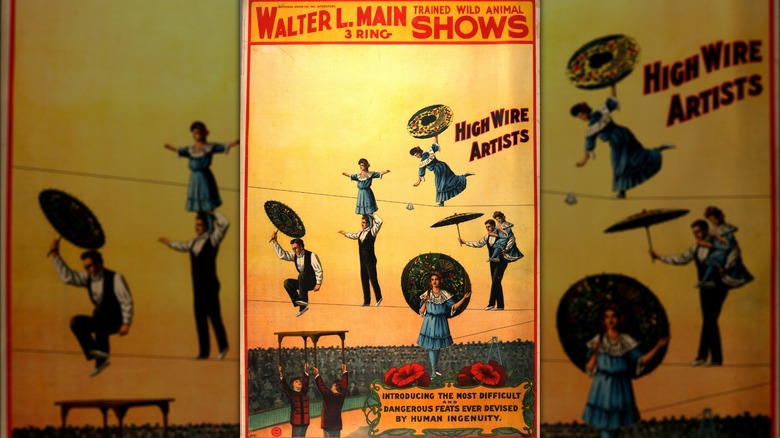

As a performer, there were many different acts that one could specialize in. Many took extensive training and skill to perform safely while entertaining the crowd. In many circuses, the most popular were equestrian acts where performers did stunts on horseback, such as one that saw Patty Astley circle around the ring incredibly fast while holding a swarm of bees. Also tremendously popular were acrobats of all kinds. In the 1860s, Jules Leotard pioneered trapeze acts, inspiring hundreds of similar acrobatic stunts in circuses around the world. Some acrobats pushed the limits, like Charles Blondin, who walked across Niagara Falls on a rope, on stilts, carrying another man on his back, pushing a wheelbarrow, and with a bag over his head (though not all at once). Clowns were also among the most beloved circus performers. Some clown acts also involved stunts, just performed in a way that was designed to make the audience laugh as well as give them chills.

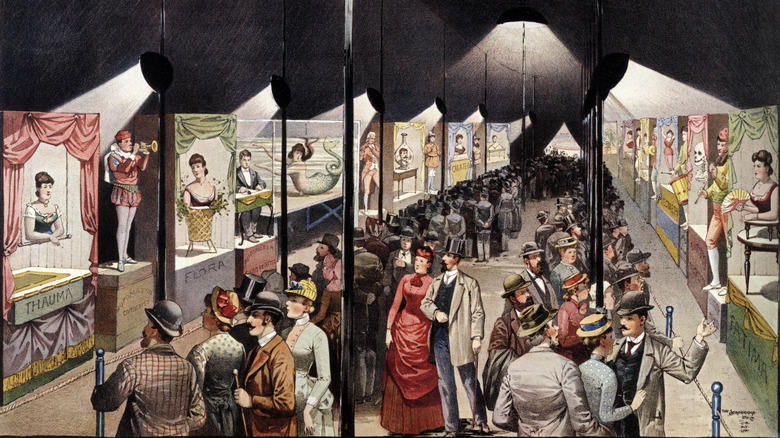

Some of the acts were as much about how the performer looked as what they could do. Acts known as "freak shows" put people with genetic abnormalities and disabilities on display. These included people with missing limbs, bearded ladies, conjoined twins, and countless others. Many of these performers weren't just passively being observed by crowds, however, and injected their senses of humor, physical strength, and skills into their acts. Some performers even intentionally altered their appearance through body modification or clever costuming so that they could join the freak show.

You didn't have to be a performer

At the height of their popularity, circuses employed thousands of people, and not all of them performed in the ring. Circuses, with their performers, animals, tents, sets, and costumes, had to be set up, broken down, and moved around the country all the time. It took a lot of people to keep the show up and running smoothly. For people who wanted to travel with the show but didn't have any skill as a performer, there were plenty of opportunities. Many of these jobs were manual labor, but the circus also needed people to care for their animals and cook and serve food for all of their employees. For major shows, like Barnum and Bailey's "Greatest Show on Earth," there would be a team of workers who traveled ahead of the circus to put up posters and promote the various acts that people could see if they came.

Non-performers could be vital members of the circus. In fact, as noted by Stuart Thayer and William L. Slout's "Grand Entrée," many of the most successful circuses had two managers — one performer who knew what the crowd wanted to see, and one non-performer who had a head for business and kept the circus running.

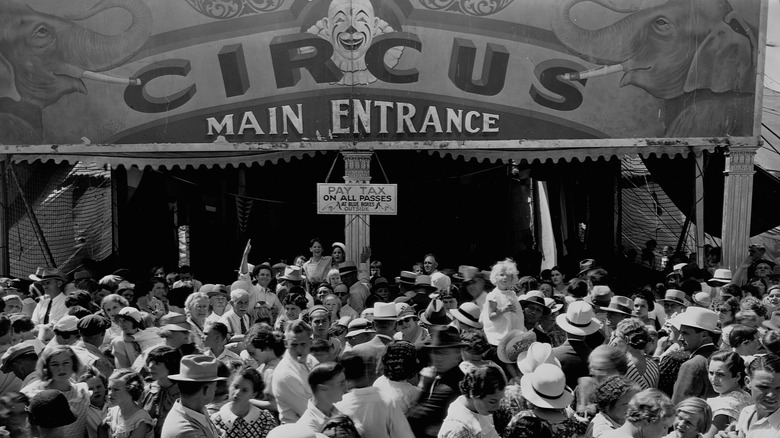

You would have to love crowds

The circus coming to town was the highlight of the year for many people around the United States. As described by Smithsonian, the arrival of the show was the only chance most small-town Americans would have to see exotic animals or performers like the ones who worked at the circus, and throughout the century, they attracted millions of people to the show. For the big shows, promoters went ahead of the circus to let everyone know where they would be, so the crowd was already waiting when the show arrived and would watch the tents go up. Even the earliest, small circuses in the United States around the turn of the century attracted hundreds of fans.

Even at times when there were no spectators present, there were enough people working for the show to keep things crowded. At Barnum and Bailey's "Greatest Show on Earth," when the circus was set up, it took up a space nearly the size of seven football fields. Everyone lived, worked, and traveled together.

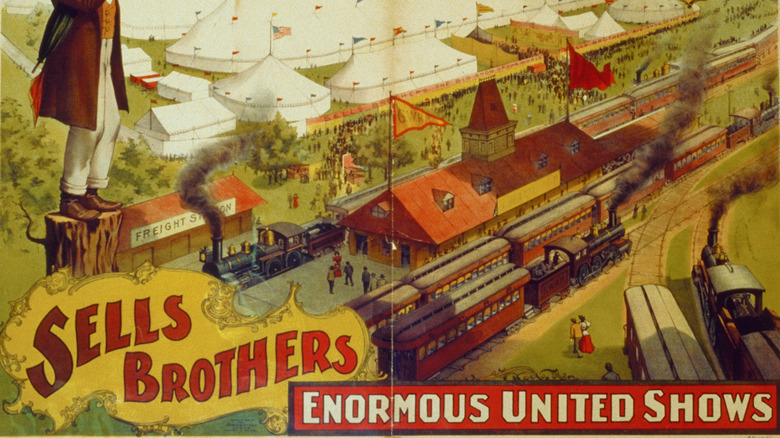

You might travel by train

In 1872, circus manager W.C. Coup hit on a way of transporting circuses and their many employees around the United States: railroads. Coup convinced P.T. Barnum to let their circus travel by train in 1871, and in 1872 the show made over $1 million for the first time ever — the modern equivalent of more than $25 million.

As described in a 1945 issue of Trains Magazine, rail transport allowed the shows to grow and travel, transforming the circus forever. It was significantly cheaper than traveling by truck, and train travel became incredibly efficient. At each location, circus workers would load and unload the train cars in the exact same way so that it was always easy to know where things were. Some train cars were dedicated to storage, with separate ones for costumes, props, and tent pieces. Animals had their own train cars, as did the human performers and workers. Some cars were essentially dorm rooms, while others were offices. The doors at the end of the cars were usually locked, so employees couldn't walk from car to car — everyone had to board or deboard via their own assigned car.

You could be injured or killed

The stunts that circus performers did delighted and shocked audiences because they were often thrillingly dangerous. Although the acrobats were trained professionals, their acts were genuinely risky and no matter how advanced they were, there was always a chance of injury or death. One beloved circus performer was a woman called Zazel, who was promoted as a human cannonball because she was launched out of a giant barrel by a spring-loaded platform. Horrifically, after more than a decade performing her groundbreaking act, Zazel missed the safety net. She survived but broke her back, and was forced to leave the circus.

One of the main attractions at the circus was always the wild animals. These often-mistreated creatures could become violent with their trainers, as happened when the famous "lion-tamer" Massarti first lost an arm to a lion during a show, and then later was ripped apart by lions in front of an audience in 1872.

Even the train travel that revolutionized the circus in the 19th century could be dangerous. An interview with a former carnival worker called W.E. "Doc" Van Alstine (via the Library of Congress) describes just how common minor train accidents were. Sometimes, the wrecks were more serious, killing or injuring many people and animals onboard. In 1889, Barnum and Bailey's famous circus train crashed, injuring or killing many animals. As noted by ncpr, even this tragedy was fascinating to the public, who arrived by the thousands to ogle the destruction.

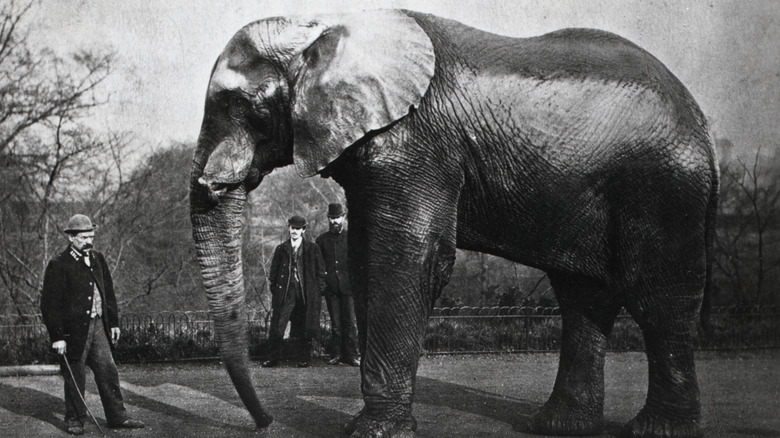

You would have to travel with animals

For many workers, being a part of the circus meant working directly with a menagerie of animals. One of the main attractions for fans of the circus was the opportunity to see wild animals from faraway places that they likely would have never seen anywhere else in their lifetime. Nineteenth-century circuses often included familiar trained animals like horses or cows, but they also might have lions, tigers, gorillas, reptiles, or elephants. Some of these animals, such as the elephant Jumbo, were celebrities known around the globe, which meant bigger crowds and more money for the show. For the workers, this meant that they had to live, work, and travel the country with wild animals.

Tragically, most workers were not equipped to care for the kind of exotic animals featured in the shows, and many of the animals who won the circus fame and fortune lived short, brutal lives. As noted in a report from CBC, the beloved Jumbo was often chained up, had bad joint issues due to the tricks and rides he was forced to perform, and had a poor diet that caused severe, painful deformities in his teeth.

You might be in it for the food

Life with a 19th-century circus could be hard work with a lot of daily manual labor, but for many workers it was worth it for the travel, place to sleep, and regular meals. As described by Dave SaLoutos, director of the Great Circus Parade, in an interview with Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, this was no accident. By the late 1850s, most circuses had a designated dining tent for their workers. For 19th-century shows that traveled by train, there would be a designated dining car and cook house. According to a 1945 issue of Trains Magazine, the dining car was often referred to as the "pie car."

This is likely because pie was often available to workers at any time. By the early 20th century, accounts describe circus cooks offering food in between meals, including coffee, sandwiches, and pie. They also served three nutritious meals a day made from fresh ingredients, including steak, pies, hamburgers, roasts, and beef and fish stews. On the Fourth of July, large holiday feasts were often served on long tables decked out in stars and stripes.

You might get into fights with locals

While circuses were a beloved source of entertainment in small towns around the United States, sometimes local people would pick fights with the show's employees. In an interview recorded by the Library of Congress, a former carnival worker called W.E. "Doc" Van Alstine explained that these fights were so common that in circus jargon there was a specific name for them: Hey Rubes.

Most of these brawls started because locals thought the circus was ripping them off. In some cases, they believed the promoters had lied to them in order to convince them to spend their money, and that the acts weren't as impressive as they'd been led to believe. Other times, locals had noticed that their wallets were missing and suspected the circus workers and performers of stealing from them. According to Van Alstine, the real culprits were pickpockets who weren't affiliated with the circus but followed the show in order to prey on the large crowds that gathered there.

Lawsuits after these brawls could hit circuses hard because the local courts were inherently suspicious of circuses and their employees, particularly if an uninvolved person got injured in the scuffle. In terms of the fights themselves, however, Van Alstine said the circus people almost always came out on top.

The acts could be grueling

While not all circus acts required the performers to soar over the heads of the watching crowd, risk being eaten by lions, or be shot out of a cannon, they could still be physically difficult and mentally exhausting. One of these acts was known as the Living Hypnotic Corpse.

As a teenager, before Tod Browning (above center) was the acclaimed director of 1931's "Dracula" and the circus-themed horror film "Freaks," he worked at the circus. As described in David J. Skal's "Dark Carnival," he was best known for an act in which he was buried alive in a coffin. Later in his career, Browning worked in vaudeville, where he learned stage-magic routines that hinged on deceiving the audience with secret compartments, but his first act was essentially real. Unlike an actual burial, it was possible for Browning to breathe (likely through a reed or some other form of ventilation that allowed air into his coffin) but in essence, there was no trick. Browning was really inside the coffin, and the coffin was really buried underground. Contrary to what the title of the act implied, Browning was not hypnotized or in any kind of altered state — he simply had to lie underground in the dark alone for hours at a time.

You could face prejudice

For many who lived and worked with the circus, the show offered opportunities they might never have had otherwise. For people with genetic abnormalities and deformities, performing in a human-curiosity act could give them the chance to earn a living, a community, and the respect of their peers. However, some of these performers had been forced into the circus, and many were exploited by the show.

White women had the opportunity to perform while traveling around the country with or without a husband. Successful women performers could become wealthy on their own terms, but as noted by Jstor Daily, in the 19th century there were many places where women were legally not allowed to perform, which made it harder for women to be hired in the first place.

For Black men, the circus was a form of employment that allowed them to avoid being in service or working on a farm. However, Black men usually found themselves hired as cooks and waiters, and were underpaid compared to white men who held the same jobs. If they were performers, they generally had to portray disturbing caricatures of African people or pretend to be some kind of human-ape hybrid in a freak show. In 1835, P.T. Barnum exhibited a Black woman named Joice Heth, who he claimed was the 161-year-old nurse of first U.S. president George Washington. In reality, Heth was an ordinary woman, likely in her 80s, who had been enslaved and sold to Barnum.

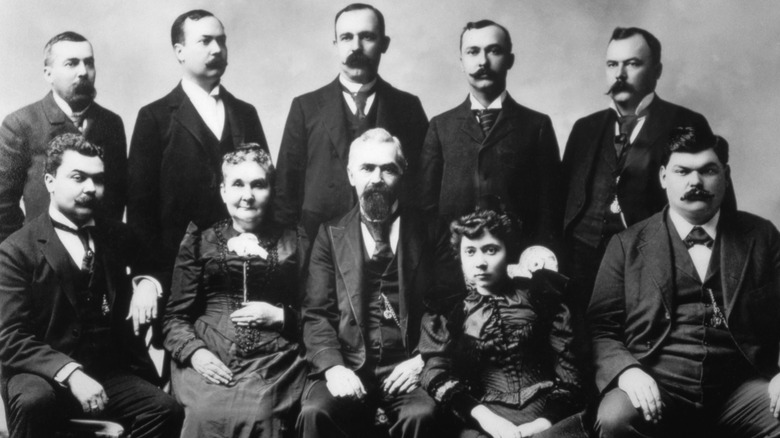

You might perform with your whole family

Many people left their old lives behind to find a new family in the circus, but for some, the circus was always home. Many families traveled together with the circus, and some even performed together in the same act. In the 19th century there were even a few famous circus families where all the members were successful performers, such as the Italian horseback-riding Cristiani family, who were known as the "Royal Family of the Circus."

Some circus families were enormous, like the Cookes of Cooke's Royal Circus, which at one time employed almost 40 members of the family. The most famous circus family in the United States is certainly the Ringling Brothers, who started with a tiny backyard circus and grew into the show that would be known as "The Greatest Show on Earth." The five original Ringling brothers had started out singing, dancing, and playing music together, but soon each would have their own specialty. Albert chose to supervise the acts, Otto managed the show's money, Alfred and Gus were in charge of promotion and advertising, Charles was the producer, and John plotted their route around the country.