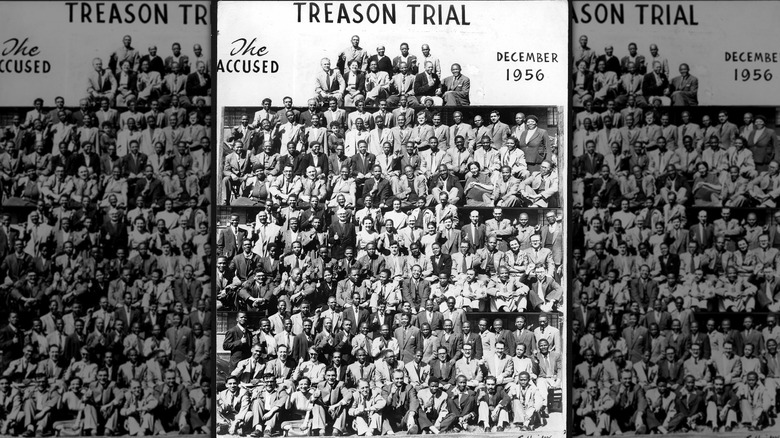

The 1956 South African Treason Trial Explained

During South Africa's apartheid regime, the government's association with apartheid was so strong that advocating for equality was considered to be an act of treason. This was made abundantly clear when over 100 anti-apartheid activists were arrested in 1956, simply for advocating for an end to the apartheid regime.

The South African government did everything in its power to try to show that advocating for equality and an end to the apartheid regime was a violent and communist endeavor. But although the court ultimately disagreed with the state, the anti-apartheid activists were stuck in the crosshairs of the state.

Despite the fact that the anti-apartheid activists were found not guilty, the fact that the trial dragged on for five years severely affected and hindered the anti-apartheid movement. Ultimately, it would take almost another 40 years for apartheid to be ended in South Africa. And the Treason Trial was just the first of many instances where the South African government showed that they were unwilling to detach their identity from that of the apartheid regime. This is the 1956 South African Treason Trial explained.

Congress of the People

In 1955, several anti-apartheid, leftist, and labor organizations in South Africa got together to create the Congress Alliance. Made up of groups like the African National Congress, the South African Congress of Trade Unions, and the South African Indian Congress, the Congress Alliance was a political coalition that pushed for anti-apartheid in South Africa.

On June 25th, 1955, the Congress Alliance put together a meeting known as the Congress of the People in Kliptown, South Africa, during which over 3,000 people from the various organizations came together to discuss the future of South Africa without apartheid. During this meeting, the Freedom Charter was created, which established the principles of a free and anti-apartheid South Africa and was adopted by all the organizations of the Congress Alliance. Unfortunately, the meeting was shut down by police after just two days on June 26th.

Three months later, many of the people who had attended the Congress of the People were targeted by police and had their apartments raided. In September 1955, hundreds of people were investigated for charges of treason, sedition, and offenses. The raids were so widespread that it was compared to a military operation, according to "The Final Prize" by Norman Levy (via South African History Online), and is known as the biggest mass raid in South African history. Although there were no arrests immediately after the raids, all the documents and recordings seized were later used as evidence for the 1956 indictments.

Over 150 arrests

Although there were no arrests directly after the Congress of the People, the South African government seemed committed to charging anyone in the opposition with treason. And although it took a little over a year, the arrests finally came in December 1956.

In the early hours of December 5, 1956, 156 people were arrested after their apartments were once again searched. But this time, they were charged with plotting to overthrow the government and replace it with a communist government, in violation of the Suppression of Communism Act. While both the Afrikaans and English-language presses reported on the mass arrests, none of them questioned or even really remarked upon the government's claims that it was about to be overthrown by communists.

After being arrested, they were taken to Fort Prison in Johannesburg, where they were forced to stand naked for hours before being taken to their cell, Peter Limb writes in "Nelson Mandela." There, they were held for 16 days. However, there was one silver lining in the mass arrests. Because the Congress Alliance had been suppressed and persecuted by the government, the fact that numerous members were all imprisoned together made it "the largest and longest unbanned meeting of the Congress Alliance in years," according to "Long Walk to Freedom" by Nelson Mandela.

[Featured image by ConstHill via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Who was arrested?

The backgrounds of those arrested varied, but all were active in left-wing and anti-apartheid struggles. Over 100 of those arrested were African, but the group included people who were white, Indian, Jewish, and mixed race, known at the time as Colored. Nelson Mandela was one of the first people arrested and was later followed by other African anti-apartheid activist leaders, including Nontsikelelo Albertina Sisulu, Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu, and Oliver Reginald Kaizana Tambo. Prominent members of the African National Congress, like Albert Luthuli, were also arrested, as were members of the Indian Congress, including Dr. G. M. Naicker and Methodist minister Reverend Douglas Thompson. And despite the fact that all were accused of plotting a communist uprising, few of them were actually communists.

Up to 14 people arrested were Jewish with Eastern European heritage. And according to "Religion and Politics in South Africa" by Abdulkader Tayob and Wolfram Weisse, Jewish people who joined the anti-apartheid struggle were severely antagonized and shunned by their communities, and told not to associate themselves with the Jewish identity.

Although those arrested were let out on bail, the subsequent trials would last almost five full years, during which the accused were forced to attend hearings every day. This served to remove the anti-apartheid activists from public life and make it impossible for them to work and support themselves, according to "Winnie & Nelson" by Jonny Steinberg.

Charged with treason

Even though the only thing those arrested were doing was opposing apartheid, they were all charged with high treason and accused of breaching the Suppression of Communism Act.

The Suppression of Communism Act was passed in South Africa in July 1950. With it, the South African government banned the Communist Party of South Africa, banned any associated publications, restricted the movements and political activities of anyone associated with communism, and justified the punishment of anyone accused of subversive communist behavior. Effectively, anyone associated with the anti-apartheid struggle was labeled a communist and oppressed, thus equating the fight for equal rights with subversive and treasonous intentions.

According to "The Courtroom as a Space of Resistance" by Awol Allo, by charging those associated with the Congress Alliance with high treason, the white supremacist South African government sought to discredit the activities of the anti-apartheid activists. Through these charges, the government also tried to insinuate that the anti-apartheid struggle was necessarily violent, in addition to being unconstitutional.

Shooting the crowd

On December 19, 1956, the 156 people accused of high treason had their first court appearance, but because there were so many of them, the court session was held in an old army drill hall in Johannesburg. Over the course of the first few days of the trial, the defendants were held in a literal wire cage in the makeshift courtroom. Only after the defense lawyers complained and threatened to walk out was the wire cage eventually dismantled, according to "Walter & Albertina Sisulu" by Elinor Sisulu.

The preliminary examination was also on the same day as the factory holidays, and, as a result, thousands of African workers showed up outside of the drill hall to show their support for the defendants. In response to the crowd of supporters, police officers were brought to suppress the crowd and subsequently fired into the crowd. During this attack by the police, between 14 to 22 people were injured by the police.

The indictment totaled over 10,000 documents and the preliminary examinations ended up taking months, before the charges against 61 people were adjourned in December 1957. In November 1958, the indictments were split into two groups of 30 and 61, whose trials would begin in 1959. Although the indictment against the group of 61 was dismissed, the trial finally started against the remaining 30 people in August 1959.

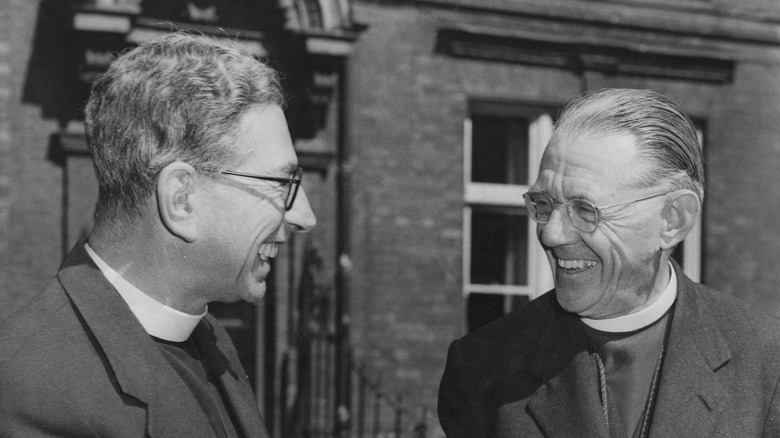

The Treason Trial Defence Fund

In order to help the defendants with bail funds, paying for the defense, legal aid, and support for the defendants' families, Anglican priest John Collins and Bishop of Johannesburg Ambrose Reeves created the South African Treason Trial Defence Fund. The Trial Defence Fund developed out of Collins' predecessor organization, Christian Action. The Treason Trial Defence Fund would later evolve into the Defence and Aid Fund for South Africa, and expand its focus and support towards all anti-apartheid and opposition movements.

On December 21. 1956, bail was granted to those who had been arrested. But because of apartheid segregation, the bail amount varied depending on peoples' ethnicity. Those who were white had to pay £250 for bail, those who were Indian had to pay £100, and those who were African or mixed had to pay £50.

Over the course of the trial, the Treason Trial Defence Fund raised at least $260,000, with more than half spent on legal defense for the defendants, writes The Atlantic. The American Committee on Africa also contributed to raising funds for the legal defense from the United States, as did organizations in the United Kingdom and Canada. In total, over $150,000 was raised by these groups.

Longest treason trial in S.A. history

Although the Treason Trial initially began in Johannesburg, South Africa, it was moved to Pretoria to avoid the crowd of African people who would show up outside the courtroom to show their support. According to "Side by Side" by Helen Joseph (via South African History Online), the Congress Alliance also had fewer members in Pretoria, which made it more difficult to organize support for the defendants.

Every day, defendants were bussed over 100 miles to Pretoria for their court appearances. But, like in Johannesburg, there was no courtroom to accommodate the numerous defendants and as a result, the trial in Pretoria was held in a building known as the Old Synagogue. From March to August 1960, a state of emergency was declared, and police detained numerous African National Congress officials, including Nelson Mandela. During their time in detention, they continued to be bussed to Pretoria for the trial.

Although the number of defendants kept decreasing, the remaining 30 were forced to face the treason charges all the way to the Supreme Court. And while the indictments for some were dropped, it was implied that the charges would be brought up once again pending the decision of the trial, since they had only been dropped because there was no difference in the two split trials. Ultimately, the five-year trial would become the longest treason trial in South African history, and the most famous.

[Featured image by Janek Szymanowski via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

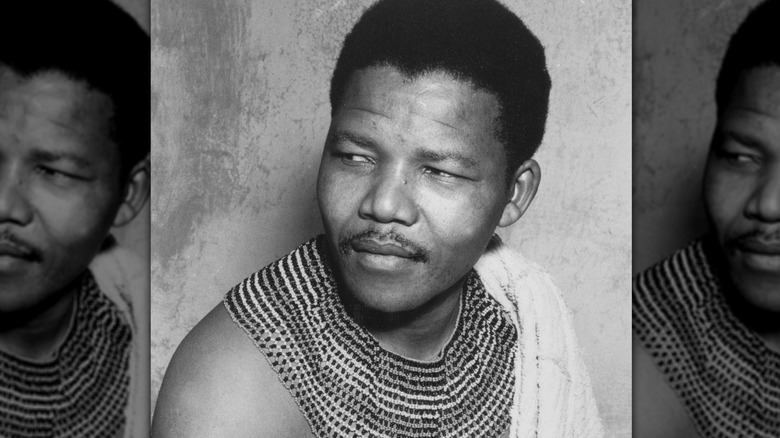

Nelson Mandela's testimony

During the Treason Trial, Nelson Mandela gave his testimony in August 1960. Although he did not initially use his law degree to represent himself or any of the other defendants, by the time he gave his testimony, Mandela was representing himself in the trial.

In his testimony, in response to the charges of violence levied against the Congress Alliance, Mandela stated, "We did expect force to be used, as far as the Government is concerned, but as far as we are concerned we took the precautions to ensure that that violence will not come from our side," per "Nelson Mandela: The Struggle Is My Life" by Nelson Mandela. During his questioning, Mandela was even asked directly if he was a communist, and he maintained that he was neither a member of the Communist party, nor did he believe in the theories of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin.

Mandela's testimony lasted six days, during which he repeatedly underlined that ideas of African nationalism and anti-apartheid struggles didn't necessitate violence. But despite the arguments that the only violence that occurred had been provoked and incited by the South African government, the prosecutors argued that "if it had not been for the restraint and tact of the police you would have succeeded long ago in involving the whole country in bloodshed," according to "The Mandela Brief" by Thomas Grant (via the London Review of Books).

All acquitted

On March 29, 1961, every remaining defendant in the Treason Trial was acquitted of all treason charges (Pictured, one of the defense lawyers, Vernon Berrange). During questioning, even state witnesses admitted that the Freedom Charter didn't advocate overthrowing the government, and that there were no acts of violence that could be attributed to the African National Congress of the Congress Alliance.

In his ruling, Chief Justice of South Africa Frans Lourens Herman Rumpff stated, "... it is impossible for this court to come to the conclusion that the African National Congress has acquired or adopted a policy to overthrow the state by violence, that is, in the sense that the masses had to be prepared or conditioned to commit direct acts of violence against the state," per South African History Online.

After the acquittal, Nelson Mandela started organizing the May Day general strike against the newly created South African Republic. However, because he was repeatedly targeted by the police, Mandela was forced to plan the strike while in hiding. And although the defendants were acquitted, the fact that the trial had dragged on for five long years had severely disrupted the activities of the anti-apartheid struggle. Numerous former defendants, including Mandela, Lilian Ngoyi, and Walter Sisulu, continued to be targeted and had their homes repeatedly raided.

[Featured image by Jevan Berrange via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

The Rivonia Trial in 1964

Unfortunately, the South African state didn't accept the acquittals. Before long, many of the anti-apartheid activists from the Treason Trial found themselves once again being arrested, charged with plotting to commit acts of sabotage in violation of the Suppression of Communism Act and the new General Law Amendment (Sabotage) Act. Known as the Rivonia Trial (after the safehouse in Rivonia, South Africa, where the accused were arrested, pictured above), the defendants included the African National Congress leaders Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Lionel Bernstein, and Andrew Mlangeni.

After a raid led to the arrests of 16 leaders of the African National Congress in July 1963, eight defendants were eventually found guilty on June 11, 1964 and sentenced to life imprisonment. Bernstein was the only one acquitted, but he was soon rearrested and eventually put under house arrest. As a result of this trial, Mandela spent the next 27 years of his life imprisoned.

Although the 1956 Treason Trial is known for being the longest and largest trial in South African history, the Rivonia Trial is considered to be the trial that changed South Africa.