This Was The First Military Burial In Arlington National Cemetery

In the spring of 1864, William Henry Christman lay in a bed in a hospital in Washington, D.C. He'd been in the Union Army for all of six weeks, according to the Historical Association of Tobyhanna Township. Christman was a member of Company G, 67th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers. Even though by this point in the Civil War, the Union had begun a draft, Christman had enlisted as a way to help his struggling family. His older brother had been killed in battle, and their father wasn't well. The money William sent home was going to be used to buy land so they could start their own farm.

Unfortunately, on May 11, 1864, Christman died not from battle wounds, but from measles and peritonitis. The 20-year-old was just one of 224,580 Union soldiers to die of disease. Even with the horrible bloodshed of the war, twice as many soldiers died of disease than from battle wounds. But unlike these others, Christman would be the first to be buried in what would become Arlington National Cemetery on the grounds of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's plantation just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C.

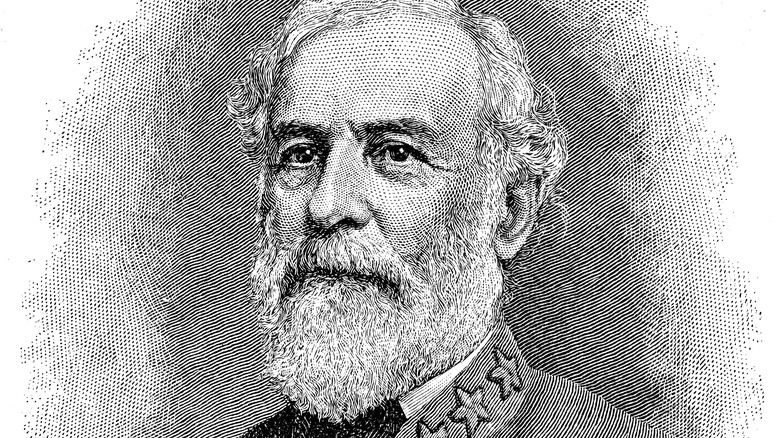

General Robert E. Lee's estate

After Robert E. Lee resigned from the U.S. Army to join the Confederacy in April 1861, he left Arlington House and headed to Richmond, Virginia. The working plantation, which Lee's wife, Mary Custis Lee, had inherited, included the use of enslaved African Americans. Mary and her children abandoned the estate a month later and eventually joined Lee in Richmond just as the Union Army prepared to seize the property.

The military used the plantation's 1,100 acres for a variety of uses, including building three separate forts there because of its strategic value as it was located on a bluff overlooking Washington. In 1863, part of the land was turned into a Freedman's Village, where formerly enslaved people lived. The U.S. Army used the mansion to house Union officers who also worked there, per "On Hallowed Ground: The Story of Arlington National Cemetery." But by 1864, Arlington became a cemetery amid the need for more space to bury the mounting Union dead.

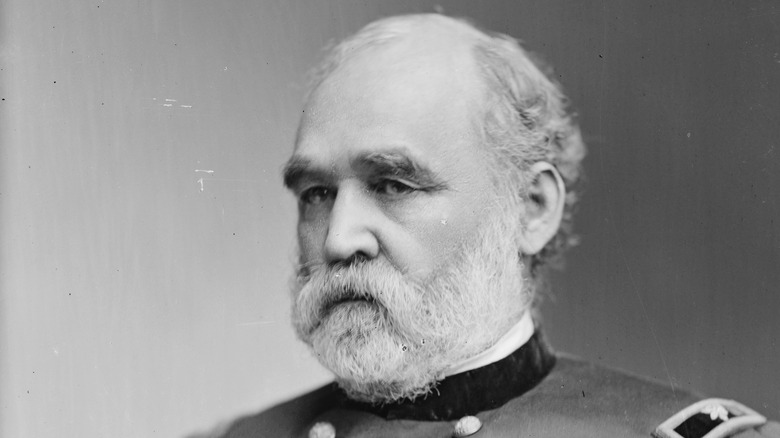

A Union general's idea

Among the many duties of Union Brig. General Montgomery C. Meigs, the quartermaster for the U.S. Army, was finding a place to bury their dead. Two military cemeteries in D.C. were at capacity so Meigs, in an act of revenge for Lee's betrayal of the Union, suggested to U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton they use Arlington as a new cemetery, according to Smithsonian Magazine and Main LIne Today. Stanton agreed to the idea.

On May 13, 1864, without pomp or circumstance, Pvt. William Henry Christman was laid to rest at Arlington, more than a month before it would be officially designated as a national cemetery. Soon thousands of other dead soldiers joined him there, their coffins stacked like "cordwood," James Parks, a former enslaved person on the plantation recalled (per "On Hallowed Ground"). Christman's sacrifice saved his family, who bought a farm and prospered thanks to the money William had sent home while serving. Today, Christman is one of more than 400,000 U.S. military personnel buried there.