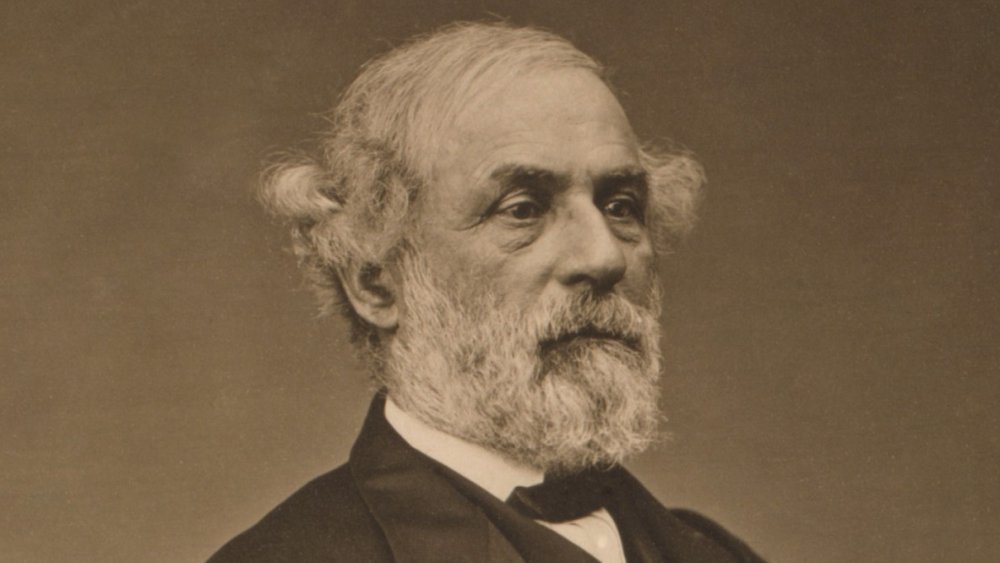

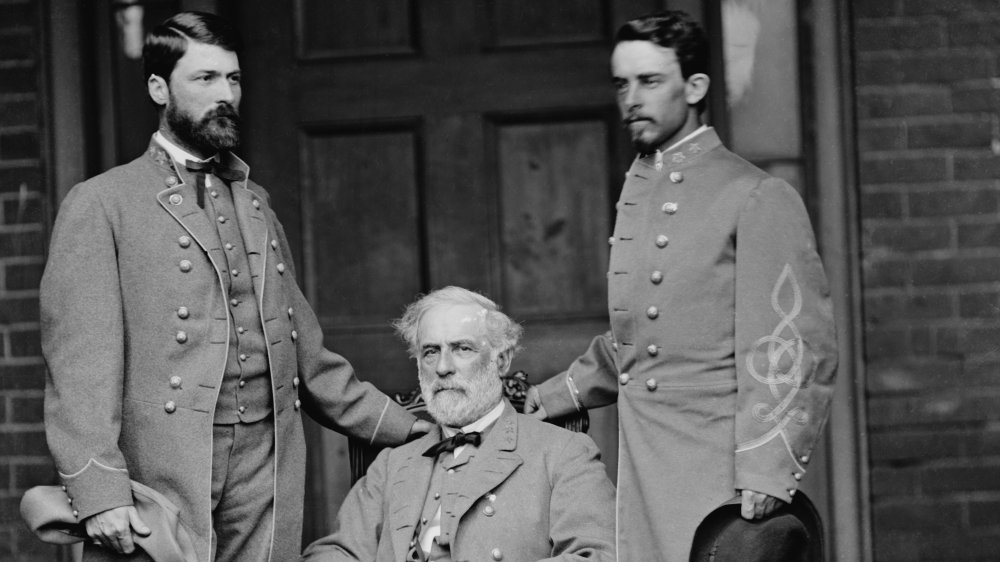

The Untold Truth Of Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee is one of the most revered, beloved generals in modern history. Many are taught that this son of a Revolutionary War hero helped lead a revolution of his own, and although it was ultimately unsuccessful, his legacy and defiant spirit have inspired millions. For a few short years during the American Civil War, Lee thwarted Union armies twice his size with bold attacks and brilliant strategy. He took the fight to the enemy and very nearly won the war for the South, all by himself. After the war, he pushed peace and humble reconciliation, earning the respect of his former foes.

Or, so goes the story, anyway. The reality is, as usual, a bit more complex than the popular version. And in Lee's case, it's uglier, too. What were Lee's actual thoughts on slavery? What about racial equality after the war? How good a general was he really? This is the real, complex, often ugly, untold truth of Robert E. Lee.

Robert E. Lee owned multiple slaves

There's no shortage of misconceptions floating around regarding what, exactly, Robert E. Lee's personal feelings towards the institution of slavery actually were. Proponents of the myth that the war was fought over "state's rights" often claim that Lee himself was opposed to the practice of owning human beings. They might even cite a letter to his wife in which he calls slavery a "moral and political evil." Later in the same letter, though, Lee goes on to support the subjugation of slaves at length and claims that only God can free them.

Lee, it turns out, owned several slaves himself. In the pre-war years, he oversaw his father-in-law's plantation and its 200 slaves, keeping them working in order to pay off long-standing legacies associated with the estate. When the operation was threatened, Lee went to court to defend it. Wesley Norris, one of Lee's slaves, claimed in that trial that Lee beat him when he was caught attempting to escape. John Reeves, author of The Lost Indictment of Robert E. Lee: The Forgotten Case Against an American Icon, noted that "every one of the facts in Wesley Norris' account has been shown to be true." According to AP News, University of Southern California law professor Ariela Gross wrote, "If you judge him by his actions, he separated families through sale, he beat slaves who ran away. He was completely engaged in the work of slave holding and supporting slavery."

Robert E. Lee strongly opposed secession

History says Abraham Lincoln's election as the 16th president of the United States in 1860 sent shock waves throughout the South, since he'd carried the contest without winning a single Southern state. Fearing domination by the increasingly powerful and industrialized North, and seeing Lincoln as an existential threat to the institution of slavery, upon which the Southern economy was built, the Southern states began to speak openly about seceding from the Union. Lincoln himself tried and failed to calm them down, saying in his 1861 inaugural address, "I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the United States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so."

The South, however, was unconvinced. Ultimately, 11 states seceded and formed the Confederate States of America. Robert E. Lee himself, a member of the US Army at the time with plans to retire, strongly opposed this. In a letter to his eldest son, Lee claimed to sympathize with the aggrieved states, but went on to write, "I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union ... Secession is nothing but revolution. The framers of our Constitution never exhausted so much labor, wisdom, and forbearance in its formation, and surrounded it with so many guards and securities, if it was intended to be broken by every member of the Confederacy at will."

Robert E. Lee turned down an offer to lead the Union Army

On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces bombarded Fort Sumter in South Carolina (the first state to secede), and accepted its surrender the following day. It was only the latest in a series of Confederate takeovers of federal property in the South, but the first time violent force had been used. Lincoln, and the North at large, had had enough. Recognizing calmer heads would not prevail and flimsy attempts by both sides to maintain peace would ultimately fail, he called for tens of thousands of volunteers to put down the insurrection by force. Both sides were galvanized, and both underestimated the resolve of the other.

During this escalation of the secession crisis, HistoryNet says Robert E. Lee was approached by Francis Blair, an advisor to Lincoln, and offered command of Union forces on behalf of fellow Virginian and army chief Winfield Scott. Lee was opposed to secession, but sympathetic to many of the grievances expressed by the new Confederate states. In the end, it was his loyalty to his native state that won out. According to Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, Lee rejected the offer and ultimately resigned from the US Army, shocking its higher ups. He said, "Mr. Blair, I look upon secession as anarchy. If I owned the four millions of slaves in the South I would sacrifice them all to the Union; but how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native state?"

Robert E. Lee's early Civil War career was pretty unimpressive

In order to defend his home, Robert E. Lee accepted a general's commission for service in the Confederate Army and was quickly put in charge of rebel forces in the western part of the state. It didn't go so well. George B. McClellan, with whom Lee would face off against frequently (and who would try and fail to unseat Lincoln in the 1864 election), had stormed through the Union-friendly region with his troops and was occupying key areas. Lee planned to begin his counteroffensive by enveloping a much smaller Federal garrison at Cheat Mountain, using information from captured enemy soldiers. However, this information proved unreliable, and rebel knowledge of the terrain was sorely lacking. The attack failed, according to CivilWar.com, with the involved brigades failing to coordinate or make contact with each other. Lee was blamed for the loss of the region, which was ultimately annexed by the North and became the state of West Virginia. Not a great start for Lee.

After these setbacks, Lee spent some time putting his engineering background to use by improving coastal fortifications in South Carolina and Georgia. His efforts were mostly successful (Savannah, Georgia, for example, would not fall to the Union until William Sherman seized it from behind in 1864), but that success wouldn't become apparent for several years. In the meantime, Lee's entrenching and fortifying only added to the perception he was overly cautious. During this period, Southern newspapers nicknamed him "Granny Lee."

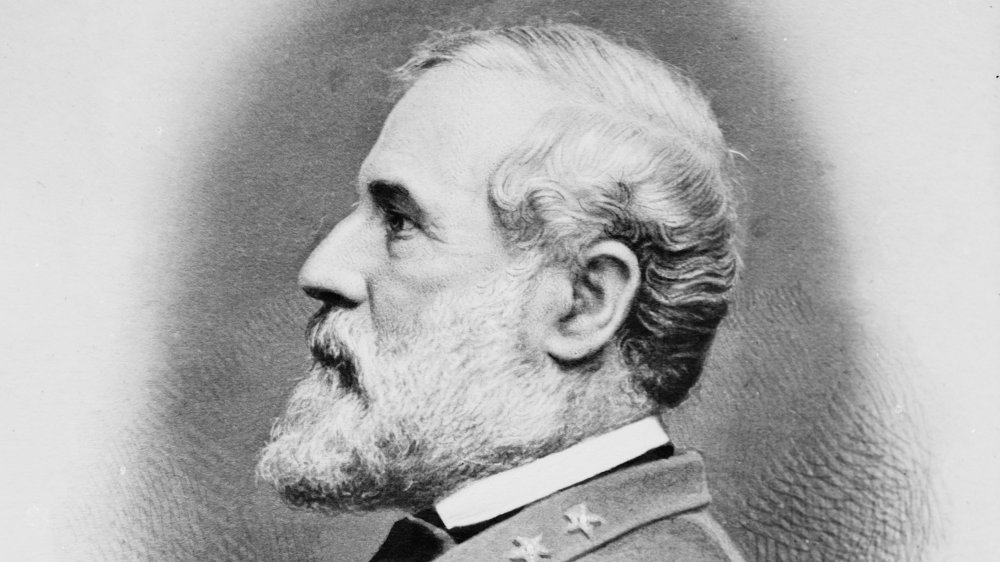

Robert E. Lee never carried out a successful offensive campaign

Robert E. Lee reversed his disappointing fortunes starting in 1862, when he took command of the Army of Northern Virginia and thwarted McClellan's attempt to seize Richmond (the Confederate capital) in the Seven Days' Battles. The American Battlefield Trust says now it was McClellan, not Lee, who looked weak in the face of a smaller enemy. As McClellan fled, Lee struck north and smashed John Pope's army at the Second Battle of Manassas (also known as the Second Battle of Bull Run), before launching his first invasion of the North. Lee believed that a victory on Union soil would scare the enemy into pulling out of the war. However, the National Parks Service says McClellan blunted this attack at the Battle of Antietam, in Maryland, and forced Lee to retreat.

Back in Virginia, Lee won two more major defensive victories at Fredericksburg in December 1862 and Chancellorsville in May 1863. The North was stunned and demoralized; Lee, despite losing his trusted lieutenant, Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, after a friendly fire incident, was now a rebel hero with fresh plans to invade the North. However, this attempt ended in another failure at Gettysburg (July 1863), and Lee retreated again. At the end of the war, he'd send Jubal Early's corps to attack Washington, but this was little more than a failed diversion. For all intents and purposes, Robert E. Lee would spend the rest of the war on the defensive.

Robert E. Lee's men routinely enslaved free Black Northerners

During its marches north, Robert E. Lee's Army lived off Union land and scared local Northerners half to death. Lee himself never allowed his soldiers to terrorize the people directly, though, with the Lee Family Archive recording he wrote "no greater disgrace could befall the army, than the perpetuation of the barbarous outrages upon the unarmed and defenceless [sic] and the wanton destruction of private property that have marked the course of the enemy in our own country." But it turns out this directive only applied to white Northerners. Black people were another story.

It's widely known Southern slave-holding states would try to recapture and brutally punish escaped slaves, which was evil enough. But Lee's soldiers would, without thinking much of it, arrest completely free Black Americans during their invasions, and send them south in chains. In some cases, according to the Post-Gazette, raids were conducted for the sole, strategically worthless purpose of capturing Black people; those who didn't hand them over would have their homes torched. Bondage for those captured this way was mercifully brief, as advancing Northern troops freed any slaves they came into contact with (as per the terms of January 1863's Emancipation Proclamation), and any who fell through the cracks were freed with the passage of 1865's 13th Amendment. Still, the fact Robert E. Lee was so willing to do this should put any remaining illusion he was a friend of Black Americans, or even a reluctant enemy, to bed.

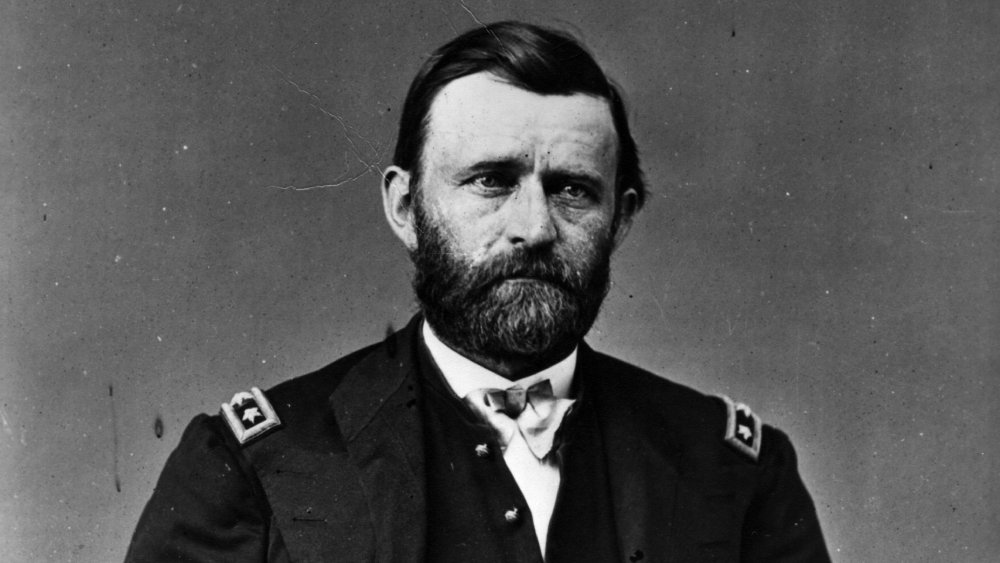

Robert E. Lee simply couldn't scare off Ulysses S. Grant

Robert E. Lee's performance in the East produced a revolving door of Union generals, each of whom either fled after defeats, or failed to destroy him after victories. By 1864, though, Lee's free ride against incompetent enemy leadership was over. Lincoln had spent the whole war searching for a fighter to lead his armies, and had found his man: Ulysses S. Grant, victor at Shiloh and Chattanooga, conqueror of Vicksburg. Grant, now in charge of all Union forces, camped in Virginia with Meade's Army of the Potomac, against which Lee was arrayed. Unlike his predecessors, he wasn't after territory: he was after Lee.

Grant also knew no fancy generalship was required to win. All he needed to do was sink his teeth into Lee and let his manpower and firepower advantages do the ugly work of wearing him down. It worked, too: the 1864 Overland campaign was a bloody, terrifying slog, according to the American Battlefield Trust, and produced few decisive victories for either side. But Grant's army only grew, despite enormous losses, and Lee's slowly withered under the constant blows. Before long, Lee had been maneuvered into the unwinnable Siege of Petersburg. For nine months, Grant slowly wrapped his massive, well-supplied forces around the city, raining shells, forcing Lee to stretch his starving, dwindling army to breaking point. Lee couldn't defeat Grant, and he couldn't allow Richmond to fall by abandoning the rail junction at Petersburg. The days of the Confederacy were numbered.

Robert E. Lee was only placed in charge of all Confederate armies in February 1865

Abraham Lincoln had spent the entire war at least trying to get his various field armies to coordinate their operations, according to US History.org. After all, they had more men and resources than the Confederates, so all they had to do was abandon needlessly complex strategies and attack everywhere at once, so the South couldn't reinforce vulnerable areas at the expense of less threatened sections. In 1864, Grant put exactly such a plan into motion: he and Butler would slam away at Lee in Virginia, Sherman would capture Atlanta and storm through Georgia and the Carolinas, and the Navy would continue to strangle ports and capture cities on the coasts.

Confederate armies tended to operate independently, and didn't develop a coordinated defensive plan until it was far too late. Only in February 1865, with the South on the verge of collapse, did President Davis finally give up control of what was left of his armies to Robert E. Lee. Lee quickly threw a plan into motion: enlist slaves to fill ranks gutted by attrition and desertion, and link up with Joe Johnston's Army of Tennessee (then unsuccessfully trying to slow Sherman in the Carolinas). It never got off the ground: just as Confederate slave soldiers were beginning to train, Grant broke through, quickly trapped Lee at Appomattox in April, and forced him to surrender. As expected, Lee's defeat led to a string of Confederate surrenders, effectively ending the war.

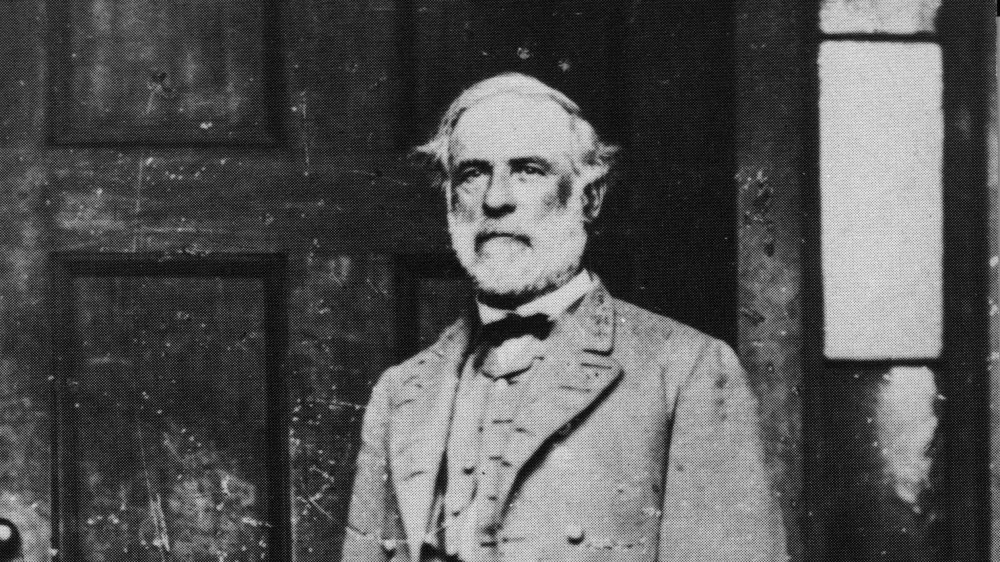

Robert E. Lee opposed racial equality after the war

Ulysses S. Grant earned Robert E. Lee's enduring admiration by feeding his beaten army and allowing it return home without further punishment. Lee himself wasn't arrested or tried for treason, although he did lose his voting rights and his family home was turned into Arlington National Cemetery. He ultimately became president of Washington-Lee University and lived the rest of his life in peace, as a battered nation tried to heal itself in the absence of Abraham Lincoln's guiding hand (the president was assassinated shortly after Lee's surrender).

Along with the question of how exactly to handle defeated rebellious states, the question of how Black Americans should be treated in post-war, post-slavery America dominated the national conversation. Lee had some thoughts, and perhaps unsurprisingly, they weren't all nice ones. He did support Reconstruction and public schooling for Black Americans, but also stated, according to The Atlantic, "My own opinion is that, at this time, they [Black Southerners] cannot vote intelligently, and that giving them the [vote] would lead to a great deal of demagogism, and lead to embarrassments in various ways." To the New York Herald, Lee also commented that "unless some humane course is adopted, based on wisdom and Christian principles, you do a gross wrong and injustice to the whole negro race in setting them free. And it is only this consideration that has led the wisdom, intelligence and Christianity of the South to support and defend the institution up to this time."

Robert E. Lee opposed Confederate monuments

In 2020 the conversation focused, not for the first time, on the celebration of Confederate leaders in military bases and state capitals across the South. Easily the most intense flashpoint for this debate is over the continued existence of Confederate monuments. Business Insider reports "of the nearly 1,800 Confederate symbols in the US... 775 are monuments and statues." The question is, what should be done with these monuments? Should they be allowed to stand, as reminders of our past? Should they be taken down, because the celebration of traitors and slave-owners is unacceptable?

Robert E. Lee himself had thoughts on this, since he was alive when the discussion of whether or not to publicly commemorate Confederate leaders like himself first began. Surprisingly, he wasn't on board with the idea. In a letter on the subject, Lee wrote (as per PBS), "My conviction is, that however grateful it would be to the feelings of the South, the attempt in the present condition of the Country, would have the effect of retarding, instead of accelerating its accomplishment; [and] of continuing, if not adding to, the difficulties under which the Southern people labour." In other words, these symbols would make it harder, not easier, for a bleeding nation to bond its wounds. And that's right from the horse's mouth. Or, at least, the man riding it.

Robert E. Lee has been nearly deified by the Lost Cause

155 years after the American Civil War ended, repeatedly debunked myths about its causes and execution, and the motivations of the men involved, remain frustratingly prevalent. Encyclopedia Virginia says most of these myths can be attributed to the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, an ideology espoused by former Confederates themselves after the war that romanticizes the South's motives and distorts history.

Proponents of the Lost Cause continue to argue the war was about state's rights, not slavery, that the Confederacy outfought the North but ran out of men, that all the good Christians were Southerners, and that Robert E. Lee was a fearless, brilliant, morally blemish-free leader. Historians and educators have debating for over a century to "untangle" myth from fact, constantly being forced to remind us that documents disproving the pillars of the Lost Cause exist in abundance, and the Confederacy wasn't a noble, Christian rebellion fighting for freedom against godless Northern hordes so much as it was a failed state run by and for treasonous, slave owners.

Yet the myths remain. The lies persist. The South lost the war itself, but the North slacked off, failing to properly support Black Americans after the smoke cleared and allowing public discourse to be poisoned with pro-South propaganda for decades. As a result, the battle over the truth and legacy of one of America's defining chapters rages on in schools and dining rooms across the country.