Famous Mobsters Who Served In The Military

In the intro speech to the 1996 movie "Gotti," John Gotti laments the decline of the Italian mafia Cosa Nostra and then accuses a "global crime syndicate" made up of various other nationalities of "[desecrating] the nation" with "no feelings for this country." For many mobsters, such a sentiment might have hit very close to home — even though the mobsters of Cosa Nostra were no angels themselves. This pride in their country had a solid foundation since, had it not been for their criminal histories, a few of the mob would be considered war heroes today.

Men such as Gennaro Angiulo, Matthew Ianniello, Edward Eastman, and Dominick Montiglio — men who also committed murder, drug trafficking, and much more — all served the United States with distinction during both World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam. Sammy Gravano was a draftee right before Vietnam. But not all of them were in it for patriotism. Some, like Lucky Luciano and Albert Anastasia, were in it for pure self-interest, whether getting a shorter prison sentence or obtaining U.S. citizenship to avoid deportation. Here are some of the more famous mobsters who served in the military.

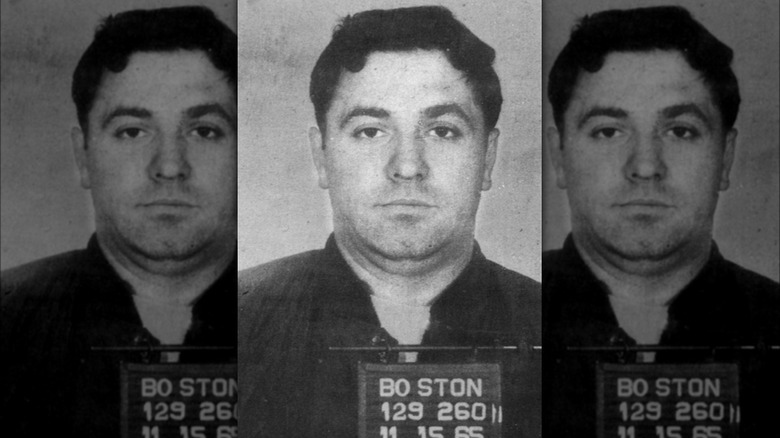

Stephen Flemmi

Stephen Flemmi was not just an associate, but the right-hand man of infamous South Boston Irish mobster Whitey Bulger and his White Hill Gang. Among his mobmates, he was known as "the Rifleman," according to a 2018 exposé from The New York Times. The two were so close that the Times called Flemmi: "in essence, the Italian-American twin of Mr. Bulger, an Irish-American." In fact, when the FBI was looking for informants, it recruited them as a pair.

Flemmi was not called "the Rifleman" for nothing. He had earned that nickname during a period of his life when it seemed he might avoid a life of crime. At age 17, Flemmi escaped the rough streets of Boston by enlisting in the army in 1951, per Boston journalist Beverly Ford's book "The Boston Mob Guide." Flemmi was sent into the thick of the action, where he earned his nickname and skills that would serve him well in organized crime.

Flemmi was assigned to the 187th Infantry and shipped out to Korea, where he thrived, spending some time as a paratrooper. He was considered a deadly sniper, racking up a Bronze and Silver Star — both awards for acts of valor. During a 2021 plea for compassionate release from prison, it was revealed that Flemmi was entitled to a monthly payment of $1,334, per The Boston Globe, due to "service-related disability," suggesting he was also wounded during his service. He received an honorable discharge in 1955, but went into a life of crime upon returning home to Boston.

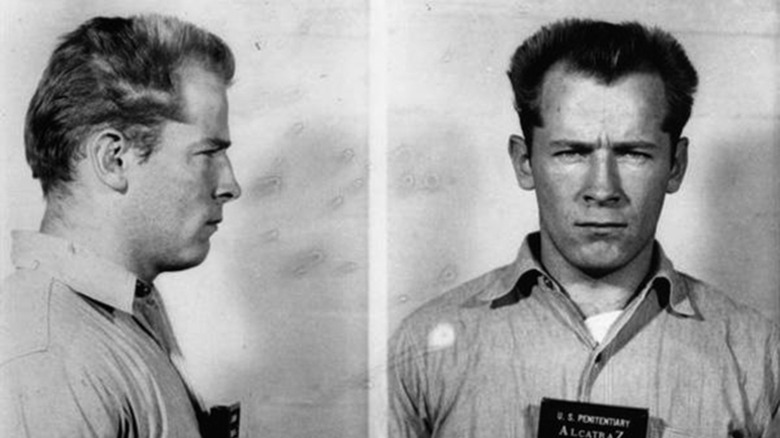

James Whitey Bulger

Head of Boston's violent White Hill Gang, James "Whitey" Bulger was the son of a longshoreman, and grew up one of three in a poor Irish family of the rough-and-tumble Southie area of South Boston. James' two brothers were model students and went on to live fruitful, crime-free lives. William Bulger, in particular, a true example of the American dream, served a quarter-century in the Massachusetts State Senate and then as president of the University of Massachusetts. James, meanwhile, cared not for school, preferring a life of theft, forgery, assault, and gang fights, earning his first arrest at 14.

Nevertheless, James got a chance to follow his brothers' success and turn his life around. After a stint in a reformatory, he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force in 1948, at 18, per the military magazine War History Online. But there would be no raft of awards for Bulger, who not only did not shape up, but continued his life of crime within the service.

Bulger's four years in the Air Force were filled with trouble. Stationed at Kansas' Smoky Hill Air Force Base, he frequently got into fights with his comrades. He went AWOL in 1950, was given a second chance, but finally received an honorable discharge in 1952. Almost as soon as he got out of the service, he was hit with federal charges for hijacking a truck and went to prison in Georgia. With that, the rest of James' criminal career path was history.

Salvatore Sammy the Bull Gravano

Salvatore "Sammy the Bull" Gravano was "Teflon Don" John Gotti's underboss, hitman, and downfall. Speaking on the Jordan Harbinger Show, Gravano explained that although he came from a Brooklyn family of "good hard-working people," he struggled with dyslexia in school, was expelled, and went into a life of street crime.

In 1964, Gravano was drafted into the U.S. Army and assigned to the infantry and communications. He was trained to run orders communications to the front line. But most importantly, he was "taught to kill." He was honorably discharged in 1966 before he could be sent to Vietnam, although he later told Peter Maas he would have been fine with it, since at least the government would have decorated him for killing people.

After the service, Gravano became a Cosa Nostra hitman. He later turned FBI informant against Gotti, partly because of Gotti's comments about Desert Storm in 1991. According to The New York Times, Gravano and Gotti were in custody and would watch news of the war. Gravano complained that "[John was] rooting for Iraq to win the war for our troops to die and this and that ... we hate the Government. But what do these kids got to do with it? I mean, like it or not, we belong to this country." This insult towards American servicemembers influenced his enmity towards Gotti, and in the end, Gravano provided the crucial evidence that finally put the "Teflon Don" behind bars.

Matthew Ianniello

Matthew Ianniello was many things, including businessman, Mafia money manager, and allegedly boss of the Genovese crime family. In his mid-80s, instead of enjoying his waning years, he was still living the life of a mobster through involvement in racketeering in Connecticut — clearly a case of someone who didn't know when to quit while he was ahead.

Before his long climb to the top of the mafia world, however, Ianniello had a sterling resume as a decorated veteran and war hero. Ianniello joined up with the U.S. Army in 1943, and was sent to the Pacific theater to fight against the Japanese. There, he distinguished himself as an artillery gunner, per the Ocala Star Banner,

During his time in the service, Ianniello was wounded and earned himself a Purple Heart, alongside a Bronze Star for valor. He then returned to New York, moving to Long Island, which had large concentrations of veterans thanks to the suburban housing boom of the late 40s and early 50s. When it seemed he had it all — including a wife, five children, and a slew of benefits — he went into the vice industry, although he maintained a respectable CEO-like posture rather than resorting purely to violence.

Edward Monk Eastman

Edward Eastman did not go into the military as a young man, intending to turn his life around. He already had nearly two decades of organized crime experience while running the streets in New York City in the early 20th century, per the Mob Museum. His gang, known as the "Eastman Gang," was involved in larceny, sex work, and some narcotics dealing. By the time he joined the service in 1917, he had at least three stints in prison before volunteering for the battlefields of Europe in World War I.

Eastman signed on as a volunteer with the 106th Regiment of the 27th Infantry Division. No one knew who he was — and he thrived. He was seen as a "tough older brother" to the younger enlistees and draftees, and had no qualms about throwing himself into the trenches in the face of enemy fire — he already had plenty of experience doing that in the streets.

Eastman saw hard action during the war, particularly during the Second Battle of the Somme in 1918. He was shot, gassed, and even charged with insubordination for leaving a field hospital to return to the fighting, despite having a leg wound. In the end, after finding out who he was, his comrades lobbied New York Governor Al Smith to pardon Eastman, after his battlefield heroics became front-page national news. However, this did not reform Eastman. As soon as he got out of the service, he went into bootlegging and got himself killed. He was given a full military funeral — ironically, with a police escort.

Moe Dalitz

Moe Dalitz was a bootlegger who used his family's laundry trucks to smuggle illegal liquor during the Prohibition Era, according to the Mob Museum. He went into illegal gambling in the '30s, after Prohibition ended. Dalitz, however, said he had always wanted to serve in the military. His brother Louis had seen fighting in Europe, while Moe had been too young by one year.

After Pearl Harbor, he claimed in an interview that he walked into a recruiting office in 1942 and signed on for active duty, wanting to fight overseas. The government, however, had other ideas. Dalitz's experience in the laundry business earned him an assignment to the Quartermasters Corps as a 2nd Lieutenant. Soldiers, the government claimed, had suffered so many privations and diseases in World War I due to filthy living conditions in the trenches and dirty clothing, and Dalitz was the perfect person to fix the army's hygiene problems.

Dalitz, in cooperation with the car industry, succeeded in designing laundry units that soldiers could take into the field, which were rolled out for use in 1943. Meanwhile, from his cushy residence at New York's Hotel Savoy-Plaza, he continued his gambling business. He left the service in 1945 with a service award and moved to Las Vegas, according to the University of Nevada, where he expanded his illegal gambling empire, while publically being a philanthropist for the local Jewish community.

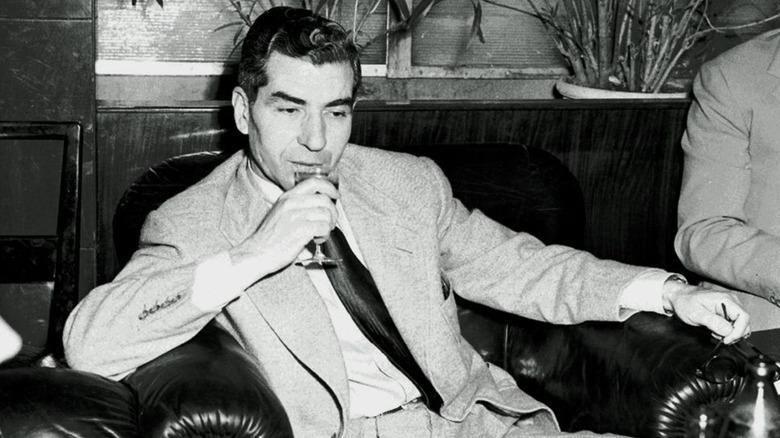

Gennaro Angiulo

In 2007, New England veterans' groups were split when the death of former Boston North End Patriarca family underboss, Gennaro Angiulo (above left), was announced. According to the Boston Herald, Angiulo was entitled to a full military funeral, complete with six Navy pallbearers, a flag-draped coffin, a bugle, and a gun salute from active service members.

As it turned out, Angiulo had earned a funeral with at least some honors. Before making a career in organized crime, which ended when violent White Hill Gang bosses and FBI informants James Bulger and Stephen Flemmi got him locked up, Angiulo had distinguished himself in the Pacific theater during the Second World War. His job was steering landing craft — a dangerous job that involved piloting boats filled with soldiers onto mined beaches, while under enemy fire. He achieved the rank of chief bosun's mate, which gave him the right to private accommodation and better food.

Angiulo's funeral raised some mixed feelings among area veterans. One said he should have "got the firing squad years ago" — military service notwithstanding — thanks to his racketeering activities and two decades in prison. However, another interviewed said that while a full funeral was probably too much given his criminal past, he had served his country valiantly before entering organized crime, while a third simply said that if he had risen so high in the military, he at minimum deserved his flag. In the end, it seems the funeral went along as planned.

Johnny Faraci

Johnny Faraci was a loan shark and soldier for Cosa Nostra's Bonanno Family, and one who could not bring himself to quit the gangster life while he was ahead. In 2002, at the age of 79, instead of golfing and enjoying retirement, Faraci found himself in front of Brooklyn judge Leo Glasser to answer corruption charges relating to bribery of a union official in Connecticut, according to the New York Post.

Judge Glasser spent the sentencing hearing castigating Faraci and his two co-defendants, telling them, "[They] ought to be thinking about getting out of that life, worrying about who's coming knocking at [their] door putting handcuffs on [them]." The judge's tirade stemmed from the defendants' age and attempts to minimize or justify their roles in the scheme. Faraci's lawyer, Vincent Romano, then thought he could pacify the judge by bringing up his client's past military service.

In a bid to win the judge over and no doubt hoping to get his client a reduced sentence, Romano told the court that Faraci had served admirably in World War II — during the Battle of Normandy (which began with D-Day), no less. He had even earned himself a Bronze Star for valor. If Romano had hoped to move the judge with his client's past heroics of charging into German machine-gun fire, he was wrong. An unimpressed Glasser had a short, yet absolutely savage, three-word response: "So did I." All Faraci could do in response was meekly apologize.

George Barone

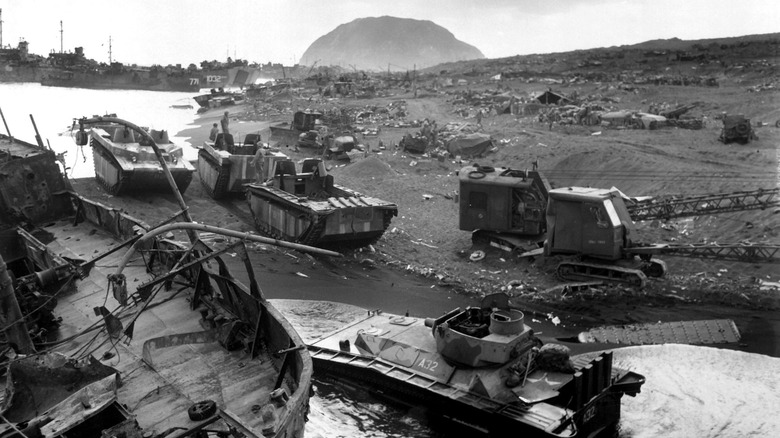

George Barone is best known for his criminal career and as the founder of the Jets street gang — eventually immortalized in Jerome Robbins and Leonard Bernstein's "West Side Story" — per the Village Voice. He later moved on to Cosa Nostra, serving as a Genovese hitman, where he racked up as many as 20 murders (that he could remember) before turning federal informant.

What is less known about Barone is that before his life of crime, he was one of "The Few, The Proud." That's right — during World War II, Barone served in the U.S. Marine Corps during its bloodiest battles against the Japanese in the Pacific Theater. According to military records, and Barone's own words to the New York Post, he participated in a grand total of five major battles, including the invasions of Guam and Saipan, and the bloody Battle of Leyte Gulf during the American invasion of the Philippines.

For Barone, however, it was his service in Iwo Jima that would have made him a hero, had it not been for his later criminal history. Although there are few specifics, Iwo Jima was the Marine Corps' bloodiest day, with over 24,000 casualties. Barone lived it all and likely experienced all the hardships, although it doesn't seem that he ever discussed his experiences in detail. He did come back with a medal for good conduct and plenty of ribbons, though. Despite attempts to make a legitimate living with the Merchant Marines, he eventually fell into organized crime.

Charles Lucky Luciano

When World War II broke out in 1939, Salvatore Lucania, better known in America as Charles "Lucky" Luciano, had been in prison for three years after Thomas Dewey prosecuted him on 62 "compulsory prostitution" charges in 1936. Although he could neither wear the uniform nor obtain an official U.S. Army commission, he found ways to serve the U.S. military from prison, in return for his freedom.

In 1942, as the United States was gearing up to enter the war, there was a concern that German and Italian agents would sabotage U.S. logistics operations around the New York City waterfront. The chief area of concern was strikes and other delays that would have direct operational implications on American forces in Europe, per Robert Kelly's "The Upperworld and the Underworld." So Luciano offered the Navy a deal: if they would cut his sentence short, he would put Cosa Nostra at the government's service to keep order on the docks.

Through a network of lawyers, racketeers, gangsters, politicians, and naval officers, Luciano kept the longshoremen working smoothly without any strikes or other problems. Under "Operation Underworld," mafia enforcers patrolled the docks, ruthlessly suppressing any word of dissent or signs of sabotage. Luciano also allegedly helped the American invasion of Sicily in 1943, by putting U.S. commanders in contact with anti-Benito Mussolini criminal elements on the island, per The History Reader, although his contribution is disputed. Nevertheless, the man who had originally put Luciano in prison — now as Governor Dewey– reluctantly commuted the mobster's sentence in 1946. Luciano was then deported back to Italy.

Albert Anastasia

Umberto Anastasio, better known as Albert Anastasia, was the capo of Murder Inc. He already had a handful of convictions under his belt by 1939, including a stint on death row for a 1921 murder of a longshoreman and a firearms arrest in 1923, according to a 1957 exposé by The New York Times. Nevertheless, he escaped the electric chair and went on to become one of Cosa Nostra's most feared figures, earning himself the nickname, "the High Lord Executioner," according to Mafia historian Thomas Hunt's site Mafia History.

By 1942, the pressure was on Anastasia, who was under investigation for a series of murders dating back to 1933. So he chose to disappear into the ranks of the U.S. Army. He signed on as a technical sergeant with the U.S. Army at Indiana Gap, Pennsylvania, where he used skills obtained in the underworld to train longshoremen to unload ships quickly and efficiently.

During World War II, foreigners who served in the U.S. military could be fast-tracked to citizenship (Anastasia had first entered the U.S. illegally in 1919). He took full advantage of the program, but omitted his entire criminal past from the application — even though newspapers had reported on his criminal history with headlines such as "Murder, Inc. Ace Now Army Top Sergeant." He got his citizenship and a discharge for being overage in 1944. Unable to ditch life in the mafia, he returned to crime and was assassinated at a barbershop in 1957.

Henry Hill

Henry Hill is known thanks to Nicholas Pileggi's 1990 crime drama "Goodfellas." Growing up in the rough-and-tumble Brownsville-East New York section of Brooklyn, Hill got into crime early on, earning his first arrest at 16 for using a stolen card to buy gas, according to Pileggi's biography "Wiseguy" — the basis for the aforementioned famous movie.

Hill had gotten involved working as a runner and soldier for Cosa Nostra. So when the U.S. Senate began investigating organized crime and published the names of 5,000 members, Hill decided to disappear from the radar. He signed on with the U.S. Army in 1960 at age 17, which took him to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where he prospered.

Hill spoke fondly of his time in the army. For a working-class kid who had never left New York, the army provided a chance to explore the world — for him, it was almost like a summer camp. He loved the physical challenges of boot camp and jumping out of airplanes. But he also honed his business skills. He said that the army frequently bought too much food that ended up getting thrown away. Having learned a thing or two on the streets, he began reselling excess food to local restaurants, putting him well above his comrades financially. After his discharge in 1963, he fell back in with his mafia colleagues, until he became an informant.

Dominick Montiglio

Dominick Montiglio was a Gambino hitman and extortionist, reportedly bringing in up to $250,000 per week in extortion money for his superiors, and according to him, the FBI believed he and his crew had been involved in nearly 200 murders. So where did Montiglio become so good at killing? He honed his skills as a Green Beret on the front lines of Vietnam.

Montiglio described his military service in a later interview, during which he noted the terrifying confusion of being in battle when all he could see were muzzle flashes, as well as his first kill — and the following self-reported 93 he accumulated as a sniper. He also joked about being the "****ing new guy," when no one would talk to him until he proved himself in a firefight. He said that while it was scary, it made him a warrior, and he did not understand why anyone would not want to experience the same.

Montiglio's comrades also remembered him fondly. In a separate interview, Vietnam veteran Benjamin Whipple spoke highly of Montiglio. Whipple said that he, Montiglio, and several other men patrolled, drank, and partied together in Saigon. On the battlefield, Montiglio, according to Whipple, took part in the bloody battle of Dak To, where he was up on the hill in the thickest part of the fighting and was wounded. Whipple did not find out about Montiglio's criminal history until Montiglio called him to tell him he was in the witness protection program.