The Complete Vietnam War Timeline Explained

Within the annals of United States history, the Vietnam War stands out as one of the most controversial armed conflicts ever. On one side, stood the United States and their allies in South Vietnam, while their enemies were the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) in the north. Just over 2.5 million U.S. personnel served in-country, with more than 58,000 dying during the fighting — over 47,000 of which were combat deaths. Yet, that pales in comparison to the millions upon millions of Vietnamese who lost their lives, the vast majority of them innocent civilians whose only crime was their place of birth.

It's difficult to put an exact start date on the Vietnam War, and the United States' involvement in Vietnam stretches back to the end of the Second World War. The first official personnel came over in the 1940s, while combat troops and heavy bombers arrived in the 1960s. After nearly a decade of inconclusive fighting, the U.S. left the country, withdrawing under a flawed and ultimately useless peace treaty with the DRV in 1973.

It wasn't until the 1990s, under President Bill Clinton, that the U.S. and the now-unified Socialist Republic of Vietnam reopened diplomatic ties in an attempt to begin the healing. However, nothing will ever undo the pain and turmoil the war caused, both domestically at home and abroad in Southeast Asia. From World War II until the Fall of Saigon, this is the complete Vietnam War timeline, explained.

The OSS and Ho Chi Minh

Most people probably don't realize it, but the United States' involvement in Vietnam actually dates back to the end of World War II. Since the late-19th century, Vietnam had been a part of a French colony called French Indochina. However, when the war broke out, the Japanese swiftly took over Vietnam in 1940, and in March 1945 they ousted the French authorities for good.

By 1944, the U.S. was involved in reconnaissance missions over northern Vietnam as part of their war efforts in southern China. Unfortunately, this resulted in at least a few downed aircraft in the area, leaving the pilots vulnerable to hostile Japanese forces. Yet, there was also another faction in the area besides the French and the Japanese: the Viet Minh. The Viet Minh was an indigenous revolutionary group led by none other than the future leader of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam: Ho Chi Minh (pictured above, white shirt). They wanted the removal of both French and Japanese occupations, and Ho saw potential allyship with the U.S. as a way to make that happen.

After Ho and the Viet Minh helped rescue downed allied pilots, they got assistance from the U.S. covert intelligence unit known as the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and Ho even became an OSS member codenamed "Lucius." The OSS trained the Viet Minh in guerilla warfare and even air-dropped them various explosive weapons and communication devices. Regrettably, the partnership would not last.

The First Indochina War

As the Second World War ended in the summer of 1945, a large power vacuum consumed Vietnam. The French had been ousted by the Japanese in March but were trying to re-exert control over the country. In September, Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), even citing the U.S. Declaration of Independence during the ceremony. Though the U.S. had allied with the Viet Minh and Ho in the waning months of the war, they fully supported the French aims to reimpose colonial control, ignoring Ho's appeals to support their independence.

While the U.S. was willing to ally with the Viet Minh during the war against the Japanese, the postwar years were a completely different story. Correctly fearing that the Viet Minh and Ho Chi Minh were communists, the U.S. refused to work with them and support their goals after defeating the Japanese.

By the final year of the war, the U.S. was paying for nearly 80% of its costs, even though it was the French who were doing all the fighting. However, the French were unable to defeat the inexperienced and under-equipped Viet Minh, leading to a disastrous defeat at the battle of Dien Bien Phu in the Spring of 1954. The First Indochina War was all but over, but the Second was soon to begin.

Geneva and Dominos

Even though the Viet Minh had beaten the French on the battlefield in the First Indochina War, they were not able to capitalize on their successes to take over the entire country following the end of the fighting. The 1954 Geneva Conference began in May just as the war was ending, with the U.S. attending as an observer.

While the accords did recognize the independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), it was anything but a complete political victory. As stipulated by Geneva, the country was to be split in half at the 17th parallel, with the communist DRV taking over the north and the non-communist State of Vietnam taking over the south. Elections to reunify the country were to be held in two years, and all troops were supposed to return to their half of the country within 300 days.

However, the accords were incredibly flawed from the beginning, starting with the fact that the State of Vietnam never even signed them. The U.S. was only an observer of the conference but nevertheless made it clear they were not in support of the agreement. The U.S. did, however, make it known they were going to be supporting South Vietnam. This was due to the belief that if Vietnam fell to communism the entirety of Southeast Asia would too, an idea widely known as "Domino Theory." The U.S. supported South Vietnam to stop communism, which they feared would consume and destroy the world if left unchecked.

The escalation of the southern war

Leading the State of Vietnam in the south following the Geneva Accords was a man named Ngo Dinh Diem. Diem was an indigenous Vietnamese politician who had served in the pre-war French government before resigning. In 1954, he became the new Prime Minister and in 1955 the President of the Republic of Vietnam, but he refused to hold the reunifying 1956 elections as mandated by the Geneva Accords.

Diem was an ardent anti-communist, and his regime was dead set on eliminating the Viet Minh — now called the Viet Cong for Vietnamese Communist — and communist threat at all costs. To this end, Diem's government was incredibly repressive, executing and detaining tens of thousands of suspected communists. Many of those killed were innocent civilians, but some were also former Viet Minh soldiers or sympathizers who had stayed behind following the Geneva Accords to sow destruction and discord in the south. Yet, by 1959 the Viet Cong's numbers were thinned out considerably.

In the north, powerful Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) politician Le Duan noted this and pushed hard for the escalation of southern violence. In May 1959, he got his wish, and the southern resistance was allowed to start limited uprisings. This led to the first official American deaths in Vietnam following a Viet Cong attack at the Bien Hoa base, as well as a massive uprising in the Ben Tre province the following January. The Second Indochina War had begun in earnest.

Counterinsurgency and the ARVN

When John F. Kennedy became the new President of the United States in 1961, it had big implications for the future of the fighting in Vietnam. During the administration of Dwight D. Eisenhower, the U.S. defense strategy can be broadly characterized as "Massive Retaliation." Massive retaliation, as you might expect, meant using massive amounts of force, including potentially even nuclear weapons, to deter communist aggression. When JFK took over in 1961, he switched the U.S. defense strategy to a new doctrine known as "Flexible Response."

Flexible response meant using only proportionate force to quell communism, which in Vietnam meant developing and using counterinsurgency tactics. Counterinsurgency focused on defeating the unconventional threat posed by the Viet Cong insurgency, which was starting to grow considerably in the south. In addition, JFK also authorized the expansion of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) from 150,000 to 200,000 men in just a few months.

However, even with expanded resources, the ARVN failed to deliver enough victories, and many were questioning their abilities as a legitimate fighting force. Still, that did not deter U.S. officials from portraying the fiction that they were successful to the American public. In the particularly noteworthy Battle of Ap Bac in 1963, the ARVN suffered an embarrassing defeat, only for officials to claim it was actually a victory.

Assassinations

November 1963 was one of the most consequential months of the entire war. In the first week, the President of the Republic of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, was brutally murdered by his generals. Then, barely three weeks later, the President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, met his own fate on the wrong side of an assassin's bullet. With both of the leaders on the U.S. side now dead, the war would never be the same.

As the Viet Cong insurgency had been heating up in the south, social and political tensions were reaching their all-time high. As part of Diem's war against the communists, thousands of innocent civilians found themselves either imprisoned or executed. This led to much discontent among the population with the government, and even an attempt on Diem's life in 1957. In the Summer of 1963, things exploded with the Buddhist Crisis and uprising, which Diem and his brother had violently put down, further enraging the citizenry.

On November 2, 1963, with the CIA's backing, dissident generals in the South Vietnamese army murdered Diem and his brother in the backseat of a van. Yet, instead of stabilizing the political situation, it only kicked off a series of coups, and the government became a revolving door for years until 1967. Kennedy died three weeks later on November 22. In his place, former Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson took over, just as the war was truly beginning to heat up.

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident

For many people, one reason the Vietnam War was so controversial was the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. It's widely accepted that the Incident played a major factor in the U.S. eventually installing ground troops and going to war, yet it was also largely based on a lie.

The incident occurred in early August 1964, less than a year after President Lyndon B. Johnson had taken over, and was actually two different episodes a few days apart. On August 2, North Vietnamese patrol boats opened fire on a U.S. destroyer, causing light damage. The U.S. considered the destroyer, the USS Maddox, to have been in international waters, but the North Vietnamese would later argue that it was within their 12-mile territorial limit. Regardless, two days later on August 4, both Maddox and the USS C. Turner Joy reported another attack from North Vietnamese boats in the same area.

However, the existence of the second attack has always been highly scrutinized. Most now believe it never even happened, but was actually the result of incorrect sonar readings. Either way, after the second attack the U.S. responded by bombing the North for the first time during Operation Pierce Arrow. In addition, the attack also led to the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, which passed on August 7 with overwhelming support. The Tonkin Gulf Resolution essentially gave President Lyndon B. Johnson the authority to introduce troops into Vietnam, a step he would soon feel the need to take.

Search and Destroy

Just after 8:00 a.m. on March 8, 1965, the first men from the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade splashed ashore just north of Da Nang in Southern Vietnam. Just under a week prior, the United States had begun a sustained bombing campaign in the north known as Operation Rolling Thunder, following the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. After nearly a decade of sitting on the sidelines and watching the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) falter and fail, the U.S. was now taking matters into its own hands. Led by Gen. William Westmoreland, by November there were just over 184,000 men in-country.

That month, an airmobile division — essentially an airborne version of the cavalry — fought North Vietnamese Army (NVA) troops in combat for the first time in the Ia Drang Valley, and it was a rousing success. U.S. forces inflicted roughly six times the amount of casualties as they sustained, and to Westmoreland, it was a complete validation of his "search-and-destroy" concept, which was largely powered through airmobile and armored units.

For Westmoreland, progress was largely measured by body counts, and higher numbers of dead NVA and Viet Cong fighters meant the war was being won. However, the use of armored units in a guerilla war based in the jungle has been subject to much criticism, with many arguing that Westmoreland's approach was flawed and was the equivalent of using a steel hammer in place of a soft mallet.

The Tet Offensive

As the Vietnam War dragged on, so did the search-and-destroy combat operations in the south. U.S. forces in the country kept growing, reaching almost 500,000 by the end of 1967. Operations were up, bombings and air strikes were up, and so were battlefield casualties — which were nearing 16,000 on the U.S. side.

Then, in January 1968, the North Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive. In a series of coordinated and timed attacks across the country, 70,000 soldiers from the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong hit U.S. and South Vietnamese installations with ferocious intensity. There was incredibly intense fighting in the capital city of Saigon, as well as in Hue and Khe Sanh to the north. Public opinion had already been dwindling on the war for years, and Tet only exacerbated the decline.

President Lyndon B. Johnson's approval ratings cratered, and newscaster Walter Cronkite's address on February 27, where he questioned the future of the fighting in Vietnam, seemed to reflect widespread discontent with the prosecution of the war.

Even though the U.S. had been fighting in force for nearly three years, the communists were still capable of launching a massive assault, leaving many to reassess prospects for winning. As a result, in March, LBJ announced he would no longer seek a second full-term in office. He then restricted Operation Rolling Thunder and opened peace talks with the North for the first time.

The tragic atrocities

While most soldiers conducted themselves with dignity and respect during the war, that was not universally true for all soldiers. Tragically, both American and Vietnamese troops committed horrifying atrocities during the war. The most infamous American atrocities were the My Lai Massacre and the infamous exploits of the Tiger Force Unit of the 101st Airborne Division.

At My Lai, it's thought that Americans killed as many as 504 Vietnamese civilians, also sexually assaulting and raping more than a dozen women and children. The only one ever really held responsible for the massacre was released after just three years in prison, while most perpetrators received no punishment. The Tiger Force attacks were widespread and occurred in many areas of the country. They included indiscriminate murder and wanton sexual assault and rape, as well as the mutilation of dead combatants.

On the Vietnamese side, there was also appalling brutality. The most infamous event is probably the massacre at Hue, when the communists killed thousands of civilians and buried them in mass graves. They also tortured American prisoners of war, both physically and mentally. It was a war largely without redemption and brought some of the most evil mankind has ever experienced.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Life for civilians

While much of the attention on the Vietnam War focuses on its political and military dimensions, there is also another vastly important aspect: the civilians. Since the outbreak of World War II and the occupation of Vietnam by the Japanese in 1940, the country was pretty much always on a war footing until the Fall of Saigon in 1975, and even then it did not stop until years later following another war with Cambodia and then China.

In the South, not only did citizens have to contend with atrocities, deadly airstrikes, and firefights happening all around them, but even the environment became unsafe to live in. Beginning in 1962, U.S. forces unloaded huge amounts of chemical herbicides and defoliants, which were aimed at eliminating the Viet Cong's food supply and source of air cover. However, it also destroyed the forest for the civilians too, taking away their farmland and sources of food. In addition, though it was not known at the time, the herbicides and defoliants would later cause huge amounts of birth defects and illnesses, affecting millions in the decades after the war.

American troops often referred to the Vietnamese in derogatory and disparaging terms, even those friendly to them — though it was often hard to tell who was friendly and who was not. The only crime of most Vietnamese was simply being born in the wrong place at the wrong time, and millions perished as a result.

Four Dead in Ohio

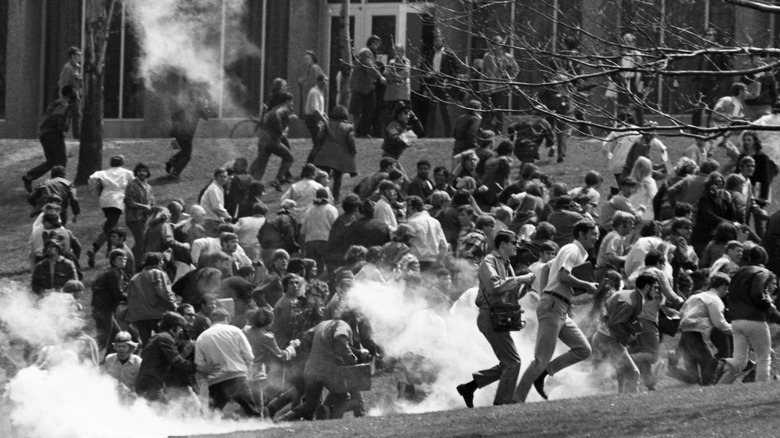

One of the biggest legacies of the Vietnam War is, ironically, the anti-war movement. Opposition to the Vietnam War began almost as soon as the war started, and by 1965 there were already protests happening throughout the country, which were largely spearheaded by college students. As American involvement in the war deepened and the casualties and costs started to skyrocket, the anti-war movement began to grow greater.

In 1967, one protest in Washington, D.C. had 100,000 participants, and soon the Civil Rights movement and anti-war movement began to overlap in places. There was also a huge music scene as part of the anti-war movement, spawning incredibly memorable songs like Jimmy Cliff's "Vietnam," Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's "Four Dead in Ohio," Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Fortunate Son," and John Lennon and Yoko Ono's "Give Peace a Chance." One of the most famous, or infamous, anti-war protestors was Jane Fonda, who later earned the sobriquet "Hanoi Jane" after taking a trip to North Vietnam and getting photographed on a North Vietnamese tank.

Sadly, the anti-war movement could turn deadly for the protestors, as happened during the tragic Kent State shooting in 1970. On May 4, 1970, four Kent State students were killed by National Guardsmen following protests that had escalated into riots against the U.S. invasion of Cambodia. Yet, the anti-war movement never stopped and was made up of both civilians and Vietnam veterans.

The secret bombings of Cambodia

By the end of 1968, the fighting in Vietnam was beginning to reach an apogee. There were still nearly half-a-million U.S. troops in the country, similar to a year prior, except combat deaths had nearly doubled to 30,000 — largely due to the Tet Offensive. In March 1969, the war entered into an entirely new dimension with the bombing of Cambodia. For years, U.S. commanders had complained about the existence of North Vietnamese sanctuaries across the border from South Vietnam in Cambodia, which allowed Northern troops the ability to escape from pursuing U.S. troops by merely crossing the border. U.S. incursions into Cambodia were limited and incredibly covert, to the point where teams wore black pajamas instead of standard Army uniforms.

Following an attack in South Vietnam by the communists, Nixon instituted Operation Menu, which was a large-scale bombing campaign against Cambodia. The bombing was kept secret from both the public and high-ranking military officials, including even the secretary of the air force — whose squads would be doing the bombing. The first public news of the bombings actually emerged just a few months later in May, but nobody took much notice.

A year later, in April 1970, the U.S. formally invaded Cambodia, drawing widespread criticism due to Cambodia's neutrality. The government would not officially acknowledge the bombings until 1973, several years and thousands of civilian deaths later.

The Pentagon Papers

Looking back today, it's hard to understate the effect the Pentagon Papers had on the Vietnam War. The Pentagon Papers are a 47-volume history of the United States' activities in Vietnam through the end of the Lyndon B. Johnson administration in 1968. The files date all the way back to the Second World War, and contain some incredibly damaging information related to the Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations' activities in Vietnam, both before and during the war.

The Pentagon Papers were started in 1967 and completed a year and a half later. They were meant to stay classified and never see the light of day, but in the Summer of 1971, The New York Times began publishing excerpts from them. The very first report referenced failures from each administration that drove the U.S. deeper into the war and was a huge embarrassment to the government. Without the Pentagon Papers, the public knowledge of the government's actions during the war would be greatly reduced.

The Nixon administration tried to stop The Times from continuing to publish parts of the Pentagon Papers but lost after the Supreme Court sided with the newspaper. Many in the public were outraged over the findings, which to them confirmed that the government had been lying publicly about the war for years. It was not until 2011 that the full spectrum of the papers was officially declassified, four decades after their existence was first made public.

Lam Son 719 and the Easter Offensive

In April 1969, there were more than 540,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam, the all-time high water mark for the war. A month later, U.S. forces participated in the now-famous Battle of Hamburger Hill in the A Shau Valley. It was a 10-day engagement that resulted in almost 450 U.S. casualties for a tactically insignificant mountain, which was quickly abandoned and subsequently reoccupied by the Vietnamese. Hamburger Hill was the last major American-led offensive of the war, as a month later in June the first large-scale troop withdrawals began.

That September, Ho Chi Minh died at the age of 79. Though no longer a political force in Vietnam, many still considered "Uncle Ho" to be the country's spiritual leader up until his death. In 1971, with the U.S. forces even further reduced, the South Vietnamese army launched the Lam Son 719 operation, which was aimed at severing the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The communists had been using the Ho Chi Minh trail since the late-'50s to push supplies south, but Lam Son 719 was a complete failure and the trail remained open.

In March 1972, the North Vietnamese launched their Easter Offensive, which captured territory in the north and further demoralized the fledgling South Vietnamese government. With most troops now withdrawn, the only U.S. response was another bombing campaign, Operation Linebacker, which was intended to pulverize the North into submission.

Bombs for Christmas

Negotiations for peace with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) had begun with President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968 and continued under his successor Richard Nixon once he took office. However, the negotiations were anything but swift and easy and dragged on for several years. In order to hasten the peace process, Nixon wanted to intimidate the DRV through his "Madman Theory." This consisted of Nixon trying to convince the DRV that he was reckless and uncontrollable and that he might even resort to using nuclear weapons to end the war.

Needless to say, the DRV did not simply melt away under the threat of Nixon being a "madman," and instead drove a hard bargain at the negotiating table. In addition, disagreements between the U.S. and South Vietnam also complicated the peace talks. Following the Easter Offensive in 1972, Nixon bombed the north and mined the harbor at Haiphong. Secret peace talks, which had begun in 1969 and went on alongside the public ones, finally began to bore fruit towards the end of 1972 after the mining.

However, the two sides were still apart on their terms, leading to what is now termed the "Christmas Bombings." Officially called Operation Linebacker II, the bombings occurred in late December 1972 and consisted of 20,000 tons of B-52-dropped bombs over Hanoi. It's thought more than 1,500 Vietnamese died in what would turn out to be the last major American bombing run of the war.

The Paris Peace Accords

On January 27, 1973, the United States and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) formally ended the Vietnam War upon the signing of the Paris Peace Accords. The treaty was supposed to conclude what had been more than three decades of war in Vietnam stretching back to World War II, but it failed conclusively. However, it did result in the repatriation of roughly 2,000 American prisoners of war, who were finally released in February following the signing of the treaty.

Yet, the accords were deeply flawed from the very beginning, and Vietnam stood no chance of remaining half-communist and half-capitalist. From a South Vietnamese perspective, the two biggest flaws in the agreement were the recognition of the National Liberation Front (NLF), and that the North Vietnamese were allowed to keep their troops stationed in the south. The NLF was the political wing of the Viet Cong and had been subverting the South Vietnamese government for the duration of the war. For them to now be a recognized and legitimate force was psychologically devastating.

As for the North Vietnamese troops being allowed to remain in the South, it was a clear recipe for disaster. The only reason the South Vietnamese president Nguyen Van Thieu even signed the accords was due to duress from the Nixon administration, who essentially gave him the ultimatum to sign it or else.

The Fall of Saigon

On April 30, 1975, the Vietnam War finally came to an end. Though the United States and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) had signed a peace treaty two years prior, the fighting still continued between the DRV and South Vietnam. Yet, by the end of 1974, South Vietnam was falling apart politically, economically, and militarily, and the end was seemingly nigh.

On March 1, the DRV began its final 1975 Spring Offensive, which portended the end of an independent South Vietnam. In a stunningly brutal display of efficiency, the DRV's troops easily pushed their way south through the South Vietnam defenses, reaching the capital in barely two months. On April 30, the last choppers flew out of Saigon, which was soon renamed Ho Chi Minh City, carrying the last American personnel. No more aid flowed from American coffers to Vietnamese purses, and the war was finally over, an incredible American defeat.

More than five decades later, questions surrounding the U.S. involvement in Vietnam still abound widely. As for Vietnam, on July 2, 1976, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam officially came into existence and is still around today.