Why Is Washington DC Not A State?

While it's rarely been front-and-center in debates over the future of the United States, the issue of statehood for the nation's capital has been a contentious one for years. A federal district since its creation, Washington D.C. has been able to elect its own mayor and city council since 1973 thanks to the District of Columbia Home Rule Act, but it remains under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Congress. Congress can repeal D.C.'s local government if it wanted to, and it has imposed limits on D.C.'s taxation powers. The district has no voting representation in Congress and is only treated as a state in presidential elections, when it gets three electoral votes.

Modern contention over D.C.'s role wasn't foreseen by the Founding Fathers, who purposely designed the capital as a district rather than a state in 1790. Its location — chosen by George Washington himself — was a compromise between competing sectional powers in the early republic. In "Federalist No. 41," James Madison said the decision was intended to prevent any one state from gaining power by hosting the federal government. Even before D.C. was established, when New York City and Philadelphia each took turns as the nation's capital, the Constitution provided for the establishment of a federal district that would stand apart from any one state.

DC statehood is tied to the civil rights movement

Washington D.C.'s degree of control over its own affairs has varied over the centuries. In 1801, it was divided into two districts — one following Maryland law and the other Virginia law. The following year, Congress granted the city its own council, though the mayor was a presidential appointment until 1812 and then a council appointment until 1820. Popular government was established that year and remained in place for several decades. But in 1871, a new law put D.C.'s affairs in the hands of a territorial governor appointed by the president.

According to The New York Times, this was in response to the District of Columbia Suffrage Bill, which made D.C. the first place in the U.S. to allow freed Black men the right to vote after the Civil War. A large number of those men came north to D.C. The laws that blunted their newfound rights denied D.C. a vote on their mayor and government officials. Efforts to restore some form of home rule were continually stymied until the civil rights movement of the 1960s, by which time D.C. was a majority Black city (per The Washington Post).

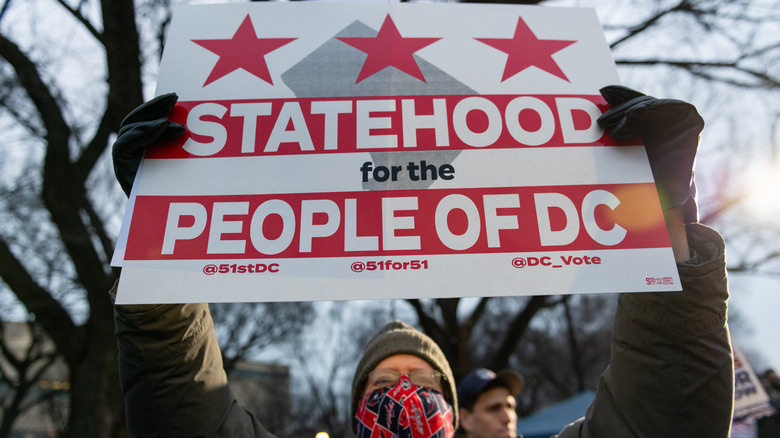

Campaigns for statehood since have invoked the language of civil rights to support their cause. The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights explicitly called it a civil rights issue, lamenting that D.C. residents "have been mere spectators to our democracy" without statehood or voting representation in Congress.

It's the will of the people

The modern campaign for Washington D.C.'s statehood began in 1980. Per The New York Times, 60 percent of voters in the district voted that year in favor of a referendum to draft a state constitution. The finished document was ratified within two years. By 2016, the share of D.C. voters in favor of statehood had risen to an indisputable majority — nearly 80 percent voted in favor of a ballot measure that would make D.C. into the state of New Columbia, with the federal district encompassing the capital shrunk to a small collection of government buildings within the new state (per NPR).

The campaigns for statehood have won D.C. some allies in the fight over the years. The League of Women Voters supports the move, as does the ACLU. The Union of Concerned Scientists has come out in favor of statehood. And lawmakers from existing states have campaigned on D.C.'s behalf. Per the Nebraska Examiner, two legislators in Nebraska introduced a resolution in May 2023 to encourage the state's congressional delegation to champion the cause, though as of September 2023 the state's legislature says no vote has yet been held on the measure.

One place where D.C. statehood doesn't enjoy majority support is in Congress. Per the Brookings Institute, a 1993 vote to consider statehood failed 153-277. Another vote wasn't held until 2021 — this effort passed the House 216-208, but it was doomed in the Senate by Republican opposition and the filibuster.

Constitutional and political obstacles remain

For the Founding Fathers, denying Washington D.C. statehood was a matter of compromise and balance. After the Civil War and Reconstruction, recalcitrant Southerners denied the district any self-government out of prejudice. In the modern era, the chief barriers to D.C. statehood are constitutional and political. Per The Wall Street Journal, the Constitution allows for new states to be created by an act of Congress with almost no restrictions. D.C. is more populous than two existing states and has clearly expressed its desire for statehood. But some, such as The Boston Globe's Jeff Jacoby, have argued that given the Constitution's provision for a federal district as the nation's capital, changing D.C.'s status would require a new constitutional amendment. Others have said that the 23rd Amendment, which granted D.C. its three electoral votes, would need to be repealed to remove floating votes in the Electoral College.

Statehood campaigners and constitutional scholars have made persuasive counterarguments that congressional approval is enough, but their facts haven't beaten back political opposition. While D.C. statehood was once an issue with support on both sides of the aisle, the Republican Party has become almost unanimously opposed to D.C. statehood. The reason? D.C. has long been a majority-Democratic voting bloc, which would likely send Democrats to Congress. Mitch McConnell allegedly used the specter of D.C. statehood and a permanent Democratic majority as reasons to protect GOP control of the Senate by acquitting Donald Trump in 2019 (per The Atlantic).