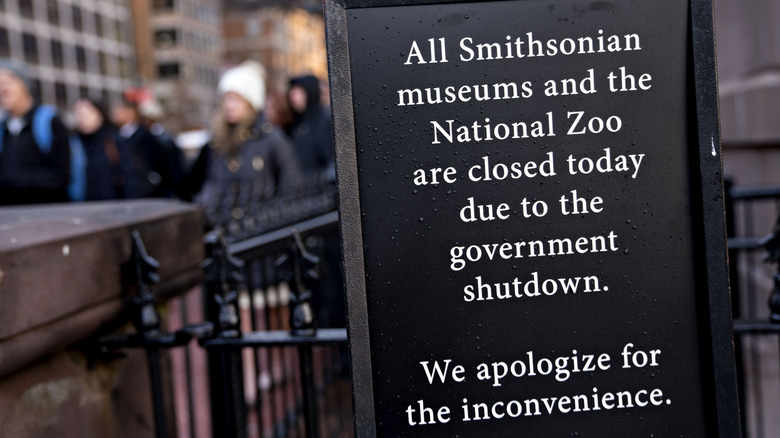

The History Of U.S. Government Shutdowns Explained

In late 2023, headlines were filled with news of an impending government shutdown... again. At the time, the most recent shutdown had also been the longest: In 2018/2019, the government stopped working for 35 days under then-President Donald Trump. The next longest was the Clinton-era, 21-day shutdown, and here's the thing — they're talked about more and more, but that doesn't mean they're less confusing.

Max Stier is the CEO of the Partnership for Public Service, and explained to CNN that "shutdown" is a bit of a misnomer. Essential services remain in place, and that accounts for about three-quarters of what the government does. He goes as far as to suggest that the term is damaging and desensitizing, because the impacts aren't immediately clear to most people. In a nutshell, he says "A short shutdown is better than a long shutdown, but it's still a terrible way to run the most important institution we have in our country."

Consequences are staggering, and could end up impacting around $5 billion in wages per week. That's just a small part of it, and Stier told ABC News, "... it is incredibly stupid. I mean, it is the equivalent of burning down your own house." Shutdowns, however, are really nothing new, so let's take a look at why they're a thing, why they're getting more severe, and just how they've changed over the past decades.

Groundwork for shutdowns was laid in 1884, and reinforced in 1974

While it seems like there should be contingency plans put in place to keep the government running in case of budget disputes, it's kind of the opposite that's true — and it's been that way for a long time. Back in 1884, the government passed a piece of legislation called the Anti-Deficiency Act. In a nutshell, it says that if Congress doesn't approve the details of how various government agencies spend their funding, they can't spend it. It sounds like they're just asking for trouble, but for almost 200 years, it worked just fine.

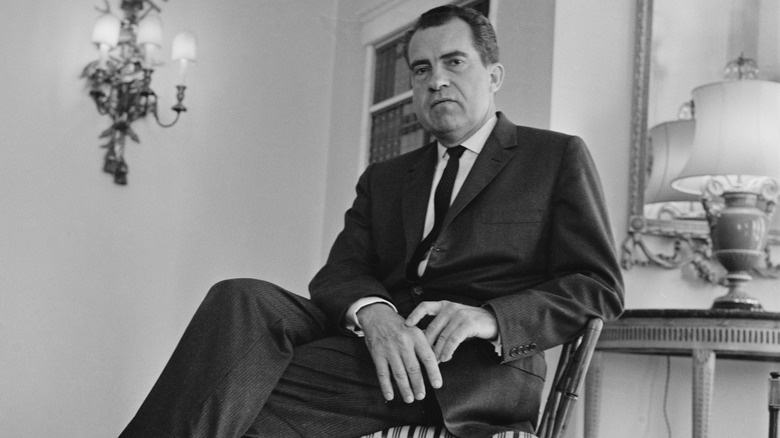

Fast forward to 1974, when Congress found itself at a budgetary impasse with then-President Richard Nixon. In order to try to avoid what earlier legislation had laid the groundwork for, Congress gave themselves some wiggle room and moved the deadline for budgetary approval from July 1 to October 1.

It made sense to move the complicated debates to the other side of the summer recess, but there was a massive catch explained by the University of California, Santa Barbara professor emeritus of economic history, W. Elliot Brownlee (via The New York Times): "We have Congress now with more leverage over the budget, but unfortunately ill-equipped politically and intellectually to handle the responsibility." Then, in 1980, the attorney general under President Carter went one step further and enacted a ruling that said any time there's a gap in funding approvals, everything needed to just stop.

The reality is a lot more confusing than it sounds

The process itself sounds pretty straightforward: There are 12 appropriations bills that Congress has to approve before October 1 in order to keep things running as planned, but as anyone who's ever had to do a group project knows, things rarely go according to plan. When the Pew Research Center put together a summary of just how often Congress managed to meet those deadlines put in place in 1974, the answer was, "Not often."

In fact, there have only been four years that they've managed to work together to pass all 12 bills by the deadline: 1977, 1989, 1995, and 1997. Mostly. Their record for passing just a few of the required bills is much higher, hitting 25% or less in 1980 through 1983, 1990 through 1994, and then pretty much going forward from there. (In 2019, they almost hit the halfway point.)

Before Congress can even start passing those 12 bills, they need to pass a budget resolution, first. That, too, had been chronically late: In spite of the fact that it's supposed to be set by April 15, data shows that in the past 49 years, it's only been resolved by the deadline 19 times. There are some instances where it's been almost shockingly late. In 2021, the budget resolution wasn't passed until just two months before the resolution for 2022 was due.

They've been getting progressively longer

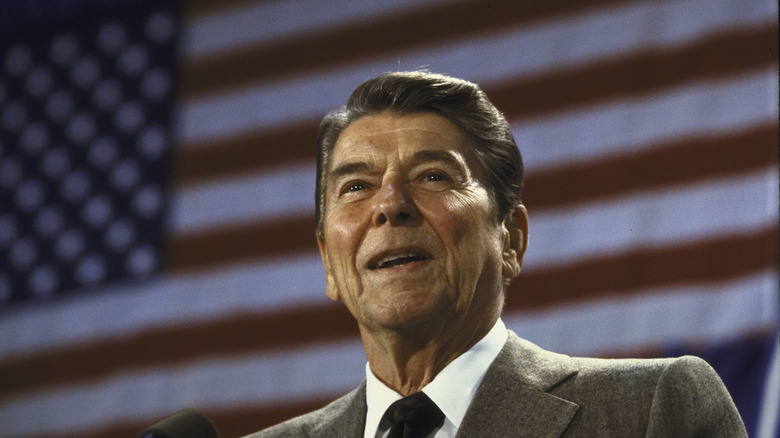

The first government shutdown happened way back in 1981 when there was a massive disagreement over domestic spending. The shutdown was triggered when then-President Ronald Reagan vetoed the bill Congress had passed, saying they needed to cut more spending off the bottom line. Things were resolved pretty quickly, and the shutdown only lasted from November 20 to the 23.

There were seven more shutdowns in the Reagan era, which sounds like a lot. Those only lasted for a few days, though, and that pattern held when there was a single shutdown under George H.W. Bush in 1990. Fast forward just a bit and things started to change.

Under Bill Clinton, there were two shutdowns, including a five-day shutdown in November of 1995, and then one of the longest in American history. That kicked off just about a month later, starting on December 15 and lasting for 21 days. After that, it seemed as though all bets were off: Future shutdowns included ones that lasted 16 days and 34 days.

The shutdowns of the 1980s were closely linked to questionable decisions by Reagan

Here's the thing about government shutdowns: While they're definitely about the country's budget, there's historically been more at stake than just how much money was going to get funneled into various departments. Back in the 1980s, there were a lot of shutdowns — although they didn't last long, they impacted hundreds of thousands of people. At the heart of the problem was the much-maligned "Reaganomics," which is ridiculously complicated and has had entire books dedicated to it.

For the purposes of talking about shutdowns, let's talk about the big reasons for those disagreements. In 1982, for example, Reagan and Congress were at odds over which was more important, putting money toward the creation of jobs, or funding weapons. (In the end, neither got the funding.)

Fast forward a bit and history saw a series of shutdowns stemming from issues that would play out over the course of the following decades and come to be seen as pretty questionable: Star Wars, support for the rebel forces in El Salvador, stricter penalties for marijuana arrests, and finally, the funding of Nicaragua's Contras. In each of those cases, Reagan wanted funding, Congress didn't want to give it, and the government came to a halt. (The exception was 1986, when Reagan and his Republicans argued against expanding the welfare system.)

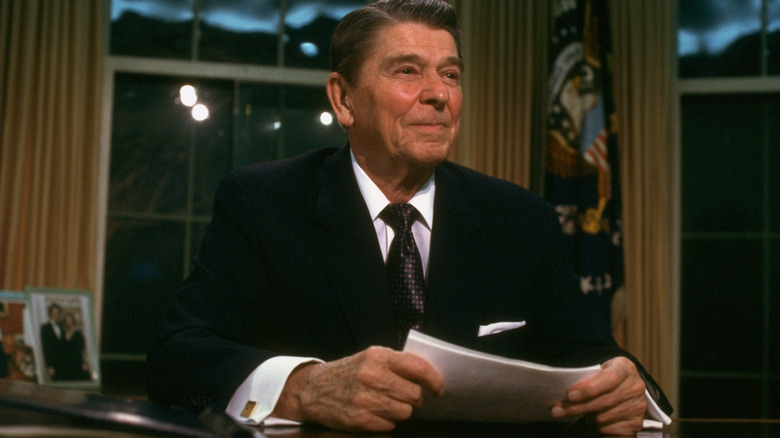

One shutdown happened because of social engagements

In 1982, the government shut down from September 30 to October 2, and here's the thing: Congress had already agreed on the appropriations bills and what they were going to contain. So, what was the problem? There was still some general housekeeping sort of things that needed to be done, but both Republicans and Democrats had social engagements scheduled and didn't want to miss them. So, they just sort of packed up and went home, leaving mass confusion in their wake and the closure of some — but not all — federal agencies.

Although they had the option to call for a late-night session and get everything buttoned up, they opted not to. Democrats were headed off to a fundraising dinner that cost $1,000 a plate (which is about $3,100, adjusted for inflation), while all of Congress had also been invited to a White House barbecue by then-President Ronald Reagan.

Edwin L. Dale Jr. was the spokesperson for the Office of Management and Budget, and assured The New York Times that it was all fine: "Everybody goes to work tomorrow," which was fine... but then, he added, "All nonessential workers may have to go into a shutdown mode ... but we do not anticipate any furloughs." That might be the most governmental thing that ever happened.

Congress continues to get paid

Perhaps most importantly, a government shutdown means that government employees aren't going to be getting paid. That includes even those deemed essential workers, who are required to report to work but who shouldn't expect to be seeing a paycheck. And that hurts: Everett Kelley, president of the American Federation of Government Employees, confirmed to CNN that many "live paycheck to paycheck, and couldn't afford to miss one payday, let alone more." But who's still getting their checks? The people responsible for the shutdown: Congress.

That's because of the legislature that governs their pay. Government shutdowns are triggered when Congress can't agree on the 12 appropriation bills, which include funding proposals put forward by subcommittees that oversee entities like the USDA and the FDA, the Department of Energy, the Department of Education, and the Department of Veterans Affairs, just to name a few. Since 1983, though, the salaries of those in Congress have fallen under a permanent appropriations bill that doesn't need to be approved.

Will that change? That's up to Congress. In 2023, Representative John Curtis (pictured) introduced a bill that would halt Congress's pay if there's a shutdown, and some members of Congress — including Virginia's Abigail Spanberger and Florida's Matt Gaetz — have requested that their pay be put on hold as a show of solidarity with other government employees.

Shutdowns about nothing have a precedent

Some shutdowns have happened because there's a lot at stake. In 2013, for example, the debate over the Affordable Care Act put everything on hold from September 30 to October 17. At other times? Michael Strain is the director of economic policy studies at a think tank called the American Enterprise Institute, and as a government shutdown loomed in late 2023, he told The Washington Post, "We are truly heading for the first-ever shutdown about nothing."

There is, however, a precedent for shutting things down over, well, not much at all... sort of. Back in 1995, the government shut down from November 13 to the 19. On the surface, the shutdown was caused because Congress and President Bill Clinton couldn't get together on Medicare, but journalist Becky Little suggests (via History) that there was a little more to it.

She says that Newt Gingrich submitted a bill to Clinton knowing perfectly well that he wasn't going to approve it, and hoped that by not approving it, he'd be blamed for the resulting shutdown. Why on earth would he do that? He told The Washington Post that he was annoyed with the president for two reasons: Clinton hadn't spoken to him when they flew to the funeral of Israel's Prime Minister, and he'd been told to leave Air Force One by the back. He admitted it was "part of why you ended up with us sending down a tougher [bill.] ... It's petty... but I think it's human."

Shutdowns ended for a while... until Ted Cruz

In 2023, U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy said (via Reuters), "Nobody wins in a government shutdown." It makes sense, then, that it would be a last-ditch effort to resolve budget debates, and for a while, it was. NPR's Washington correspondent and editor Ron Elving explained that over the years, most people have learned that "Shutdown wars, it turns out, are like some other kinds of wars that eventually end without a clear winner. ... If shutdowns do accomplish anything, it's the energizing of political parties. Shutdowns have not been popular with the public, but they can be highly stimulating for donors and activists."

Enter Ted Cruz. In 2018, he sort of mind-bogglingly denied being a supporter of government shutdowns, in spite of the fact that he spearheaded the movement behind the 2013 shutdown. The Washington Post called it "a defining moment" in his career, and then-senator Tom Coburn explained that it actually wasn't about Obamacare or the budget at all, not really: "It wasn't about the shutdown. It wasn't about the Affordable Care Act. It was about launching Ted Cruz."

Cruz famously spent some time reading "Green Eggs and Ham" on television to make his point, and in the end, the government not only was shut down for 17 days but absolutely nothing came of it. By the time votes went through to restart business as usual, they came with none of the changes to Obamacare that Cruz had been campaigning for in the first place.

Shutdowns have become more likely

Li Zhou is a political reporter for Vox, and in the lead-up to a potential 2023 government shutdown, she described the possibility of shutdowns as getting "more plausible in recent years." She said that after the short-term shutdowns in the 1980s and the few but substantial ones in the 1990s, Congress started seeing it as a last-ditch effort. They can, after all, pass short-term bills to keep things functioning, but adds that what was once a rarity has become — and is likely to continue to be — a regular threat. Why? Simply put, because the left and the right are moving farther and farther apart and compromises are becoming less and less likely.

She explained, "Since these are routine, must-pass measures, they offer a prime opportunity for lawmakers to use what leverage they have to send a political message to their base. Although Republicans were blamed for a shutdown in 2013 ... it still played well with many of their supporters, underscoring how these deadlines could be an opportunity to energize GOP voters."

Control of the House and Senate passes between Republicans and Democrats, and throwing in the massive political divide has created something of a perfect storm. Instead of working together to get things back on track, analysts say being difficult and not compromising has led to an increase in support from the populace, which increases the chances a non-controlling party will rally voters to take over next time.

Here's how impacts have changed

The varying length of time that government shutdowns have lasted — along with things like the cost of living and how many people are living paycheck to paycheck — means that comparing the impacts of government shutdowns is a bit like comparing apples to oranges, but there are some things to consider. Take the number of people who were put on furlough. When the U.S. government shut down in 1981, it impacted 241,000 employees for just a few days. Fast forward to 2018/2019, though, and that involved around 800,000 people who were sent home for a little over a month.

What shuts down and what keeps functioning is anything from straightforward. Essential workers — such as law enforcement, many military personnel, customs agents, and Homeland Security agents — are ordered to report to work, but pay? That's iffy. Lawmakers in Congress, for example, continue to work and get paid, but at the same time, their staff is also required to work... and they don't get paid. Training halts for many places — like the Transportation Security Administration — and organizations that don't rely on the government for funding (like the Post Office), continue as usual.

But what about those people who are deemed essential workers, but don't get to collect a paycheck? It wasn't until 2019 that the Government Employee Fair Treatment Act was signed into law, meaning that workers would eventually get the back pay that they were owed... mostly. The bill didn't cover subcontractors, an oversight that 2023 legislation was hoping to remedy.

Everyone who eats is and has been impacted

It's easy to overlook some of the ways that the government keeps everyone safe, and that extends to the country's food sources. There's plenty that can go wrong, and government organizations like the FDA, the USDA, and the CDC are usually on the front lines of making sure that doesn't happen. When the government shutdown kicks in, though, that's when things can — and have — gone sideways.

In 2013, 52% of employees from the Department of Health and Human Services were furloughed, along with 68% of employees from the CDC. Wired looked at what that meant and found that not only did it mean the end of rapid response teams for outbreaks of illnesses like the flu and measles, but it also meant that they weren't going to be tracking outbreaks of food poisoning that could potentially span states. While food inspections continued, outbreak management was going to be at a low. Did one happen? Yes.

When an 18-state salmonella outbreak sickened hundreds of people, the Food Safety and Inspection Service issued a statement that read (in part), "FSIS is unable to link the illnesses to a specific product and a specific production period. The outbreak is continuing." Wired reported that CDC scientists couldn't even work voluntarily — they were locked out of their offices.

Talk of ending the potential of shutdowns completely hasn't gone as planned

There's a shocking cost to government shutdowns, and that price comes from a wide range of places. Consequences were summed up by Marc Goldwein of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (via The Washington Post): "We pay federal workers their regular salary, in many cases, not to deliver government services." That includes, for example, collecting fees, donations, and processing purchases at national museums and parks, which brings in a ton of money. The financial cost of a government shutdown can easily rise into the billions of dollars, so it makes sense that lawmakers might want to, well, not have a shutdown.

In 2019, that was actually the goal. The New York Times reported on a bipartisan discussion that pitched the idea of walking things back and making it so shutdowns were no longer an option. Tennessee Senator Lamar Alexander explained: "Shutting down the government should be as off-limits in budget negotiations as chemical warfare is in real warfare."

And it wasn't anything new. Former Ohio senator Rob Portman (pictured) had been campaigning for years for the passing of legislation that would essentially mean that if Congress didn't hit its appropriations approval levels, it would trigger a backup plan that would initially keep funding at current levels, then gradually reduce that funding as months rolled on. Fast forward to 2023, and the plan was still being talked about, alongside another shutdown.