How The Real Osage Murders Changed The Reputation Of The FBI

J. Edgar Hoover's administration of the FBI has acquired a grim reputation in the years since his death. A steady drip of revelations about illegal surveillance, racism, blackmail, Cold War hysteria, and astonishing neglect over the dangers posed by the American mafia will tend to do that to a man's image. Yet if Hoover had unsavory traits and could favor dangerous tactics, he also had a pragmatic side and a dedication to law and order (per The Atlantic). Appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation (later the FBI) in 1924 while still in his 20s, Hoover maintained his grip on the agency for decades through careful politicking and genuine law enforcement. An upright, nonpartisan reputation that only gradually eroded through the decades got an early boost through the bureau's work investigating the Osage murders.

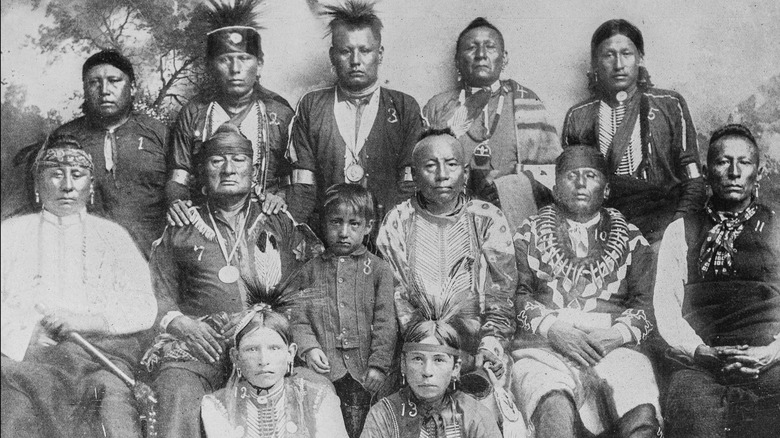

Per History, the Osage, a Native American Tribe, were originally from Kansas before they were forcibly relocated in the 19th century. They made their new home in a part of northeastern Oklahoma. When the Osage bought the land, they also bought the mineral rights, which paid off handsomely when oil was discovered. The fees paid by oil barons made the Osage, who each received royalties, very wealthy people by the 1920s. In 1923 the tribe took a payout out of $30 million, equivalent to 540 million in 2023. With success, however, came jealousy from white neighbors — jealousy that culminated in murder. The Osage killings became the FBI's first large-scale case, and it helped salvage the bureau's reputation — though not without cost.

The FBI saw the Osage case as a chance to clean up their image

The scale of crimes inflicted upon the Osage nation is difficult to quantify. Per History, Government-imposed "guardians" facilitated swindles and inflated prices designed to bilk the Osage out of their oil money, and sometimes permitted or engaged in outright theft. Others embarked on an elaborate plan that took advantage of inheritance restrictions that only let Osage will their shares of oil profits to their kin. People married into Osage families, killed their spouses, and came into the money the oil shares represented. There were at least 24 murders in Osage county between 1921 and 1926 according to the Financial Times – murders local and state authorities turned a blind eye to.

As the Osage suffered injustice from local law enforcement, J. Edgar Hoover was trying to clean up the image of the Bureau of Investigation. It had first been formed in 1908 under Theodore Roosevelt and had quickly devolved into an underhanded department with a penchant for political surveillance (per The Atlantic). Hoover played his part in such intrigues when first appointed to the bureau, but when Attorney General Harlan Stone made Hoover acting director, it was with a clear mandate to turn the agency into a professional law enforcement group, trained in new investigative techniques.

The Osage approached the bureau for help just as Hoover's rehabilitation efforts (which included dressing agents in conspicuous suits) were underway. He saw his chance to demonstrate what the bureau could do and took it.

The investigation brought (some) justice to the Osage

The Bureau of Investigation's initial efforts to solve the Osage murders did not go well. Per History, an attempt to make an undercover agent out of outlaw Blackie Thompson didn't achieve anything except letting a violent bank robber out to commit more crimes, including murder. J. Edgar Hoover was tempted to pull out of the case altogether. But his agency needed a demonstration of professionalism and competence; besides its earlier uncouth tactics against politicians, it had been tainted by the Teapot Dome scandal of the Harding administration.

Things turned around through the efforts of agent Tom White, a former Texas Ranger dispatched to Osage County. White and his team of operatives zeroed in on the murders of the family of Mollie Burkhart, who lost her three sisters, her mother, and a cousin within a five-year time span under suspicious circumstances. Burkhart had inherited her family's oil shares and became the target of murderers and poisoners herself (per Tulsa World). The investigation uncovered a sordid plan by Burkhart's uncle-by-marriage, community leader William Hale, to snatch up oil shares from the Osage by deceit and murder. Burkhart's husband was also implicated in the crimes.

White's efforts helped clean up the bureau's reputation and brought some justice to the Osage, though Hale wasn't convicted until 1929 (per the University of Arkansas). And the justice won was limited; Hoover prematurely ended the investigation, leaving many murders unconnected to Burkhart unsolved. He also charged the Osage $20,000 for his agency's efforts.