The True Story About Oskar Schindler From Schindler's List

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In 1993, the world was captivated by Schindler's List. It would become one of the defining films of Steven Spielberg's career, and the process of making it alongside another blockbuster — Jurassic Park — was so draining that The Guardian says he had a weekly conference call with Robin Williams, who spent 15 minutes on the phone with him just to make him laugh.

Few films have had such a lasting impact on the way the world thinks of a piece of history, and this one took the overwhelming enormity of the Holocaust down to a microcosm centered on the profiteer-turned-savior Oskar Schindler, the sadistic SS officer Amon Göth, and a little girl in a red coat.

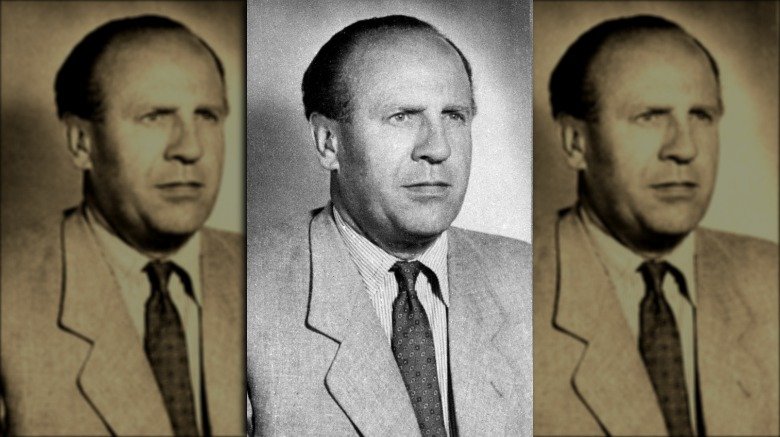

Schindler's List took home a slew of Oscars, but there are things more important than awards and accolades. More important is the true story. It was first told to author Thomas Keneally, recounted by one of men Schindler had saved. Keneally novelized the story into the book that would ultimately inspire Schindler's List, and Schindler himself? He was very real, was born in 1908 (via Biography), and died in 1974 — long before his story unfolded on the big screen. How much of his on-screen portrayal was accurate?

In Emilie's words

One of the people who knew him best was his long-time wife, Emilie Schindler. She's portrayed in the movie by Caroline Goodall, but before her death in 2001 (via The Telegraph), the real Emilie was incredibly outspoken about the history behind the Hollywood.

Born Emilie Pelzl in 1907, she was 20 when she met her future husband. He was working alongside his father, and they had stopped by the Pelzl household to sell motors that would harness the power of electricity for them. They were married not long afterwards, but she was very vocal about how it was never an easy relationship. Even Thomas Keneally, the author of Schindler's Ark, later admitted that if he had met her before writing his book, he would have written it very differently.

During interviews (via the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum), Emilie gave some candid insights into the man she met before the war, saying, "Herr Schindler was very sympathetic. He knew very well how to talk. He talked a lot, even if it was not the truth... he knew how to influence people."

She painted a picture of polar opposites within the same person, saying his actions began out of a definite self-interest and a desire for cheap labor to run his factory. She called him a coward fond only of liquor and women, while also asserting he was never, ever anti-Semitic and truly counted Jewish workers among his friends... and mistresses.

Espionage, arms-smuggling, and aiding in the Nazi invasions

The real Oskar Schindler was definitely no saint, and long before he headed up a factory filled with souls he would save, he was a spy for the Nazis.

Between 1936 and 1940, Schindler was an active member of the Abwehr, Germany's military intelligence. Stories vary as to how this came to be. According to Leger, Schindler joined up after meeting Abwehr chief Admiral Wilhelm Canaris while mingling at a party, while The Independent says he was recruited into the intelligence agency by one of his many mistresses.

Either way, by 1938 he had gathered maps and information on military defenses in Czechoslovakia, amid the Nazi's annexation of a section of the country. He was arrested for espionage and was sentenced to death in 1939, but his release was secured amid the Munich Agreement. His role in the relentless march of the Nazis into Poland was even greater, and he not only smuggled weapons across the border, but played a key role in securing crucial railway lines. While that invasion was ultimately scrubbed, JewishGen says he worked under the names Zeiler, Osi, Otto, and Schofer, and that he took his work very seriously.

No intentions of grandeur or selflessness

According to David M. Crowe's extensive research into the real Schindler (via the London Evening Standard) there are two different people: the historical Schindler, and the one plucked from the pages of Thomas Keneally's novel. The real Schindler, they say, originally had no aspirations to save lives or become a hero to thousands. At first, he only came into contact with Jewish laborers because they were cheap workers.

Schindler's original crew included six Jewish workers and 250 Polish ones. He found that not only were the Jewish workers cheaper to buy from the SS, but because they were so terrified they would find their lives forfeit if they were thought to be useless workers, they made sure they were very, very good workers. Crowe says (via Forbes) that when Schindler first set up his factory in Krakow, his goal was simple: make money. The Jewish workers were simply a way to minimize costs and maximize profits, and it was similar to the way most other Nazi entrepreneurs viewed the slave labor they bought.

Enamel and munitions

According to the Jewish Virtual Library, Schindler headed into Poland with the rest of the Nazi Party, and once he got there, he turned to black market dealings to make a hefty sum of money. After getting in good with the higher-ups, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum says he used his contacts and the Nazi desire to "Aryanize" businesses to buy the Jewish-owned Rekord Ltd. in October 1939. Within the month, he converted it to an enamelware factory called the Deutsche Emalwarenfabrik Oskar Schindler, or Emalia.

Schindler repeatedly bribed officials to help keep his workers safe, and when Nazis "liquidated" the Krakow ghetto, Schindler kept his workers in the factory overnight, thus keeping them alive. It wasn't until 1944 that Schindler opened an armaments plant in Brünnlitz, and went to the SS with a list of Jewish workers who were, he said, essential to his efforts. It almost didn't work.

According to The Telegraph, Schindler got some major pushback from the mayor of Brünnlitz when plans to open the factory went public. The problem? Those factories were high-priority targets for Allied bombers, and it would put Brünnlitz on the map. That's when the most unlikely thing happened. Emilie Schindler stepped in, and said she would take care of it. She met with the mayor — who was her old swimming teacher — and after a bit of reminiscing about better days gone by, she got her husband his permit.

Schindler didn't write the list

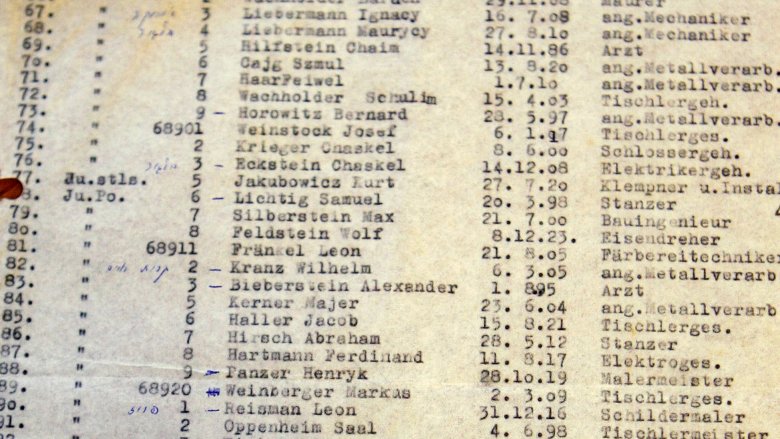

It's called Schindler's List. It's what he's most famous for, and it's what defines him. But there's more to the story than that, says David M. Crowe (via The New York Times).

There were actually multiple lists (sources vary between seven and nine), including one that went up for sale in 2017. That one, says The Guardian, was typed up by Itzhak Stern (who was played by Ben Kingsley in the film) and was said to contain names compiled by Schindler, Stern, and Mietek Pemper, a concentration camp inmate and secretary of Amon Göth.

There's a huge but here, says Crowe. According to documents he found in his research, Schindler was actually in jail at the time he was supposed to have been writing up his list. Instead, Crowe says the author of at least four of the lists was Marcel Goldberg, described as "a corrupt Jewish security police officer and assistant to an SS officer." Crowe says it's not clear who wrote the others, but suggests Schindler was so closely associated with the idea of the lists because he stepped in to take credit for that particular part of the story.

A life anything but black and white

Schindler's story is fascinating — in part — because he was about as far from the knight in shining armor as anyone can possibly get, but he still showed breathtaking bravery, put his life on the line for those who had no voice, and saved hundreds of lives. According to David M. Crowe's biography (which was written with access to piles of documents unavailable to earlier author Thomas Keneally, says Forbes), Schindler was not always the type who seemed destined to do great things for people.

It was only after he spent time working alongside those he had hired — cheaply — that his sympathy for their plight began to form. Schindler, Crowe says, never agreed with the policies and programs that came from the black heart of Nazi Germany, and adds that the film's depictions of a few major events (the girl in the red coat, witnessing the mass murder in the Krakow ghetto) that changed Schindler forever were simply creative license. "In the end, there was no one, dramatic, transforming moment when Oskar Schindler decided to do everything he could to save his Jewish workers," Crowe wrote. He continued, "During the last two years of the war, he had undergone a dramatic moral transformation, and, in many ways, he came more and more to associate himself with his Jews than with other Germans."

Knocking on the concentration camp's door

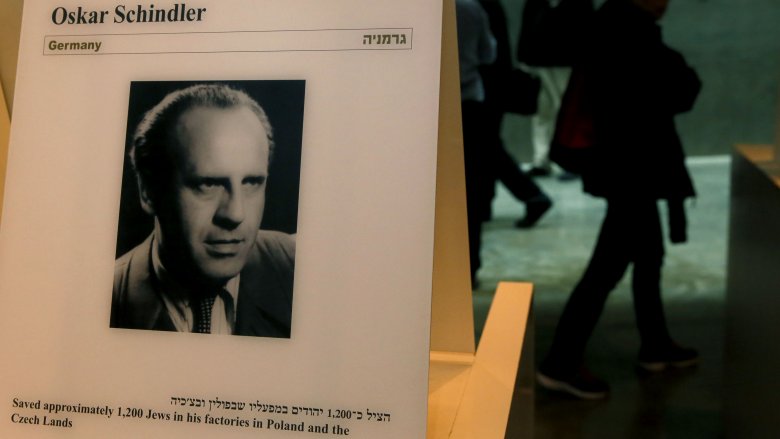

Yad Vashem named Schindler and his wife Righteous Among the Nations in 1993, and they're also the stewards of a series of artifacts that he gave to those he saved in hopes it would help them start new lives after the war. They also say that not only did he falsify records, list women and children as valuable factory workers, and lie to the SS officers who came knocking on his door, but that when push came to shove, he wasn't afraid to go knocking on their doors, either.

In 1944, the camps and sub-camps of Plaszow were evacuated ahead of the Soviet army's arrival. Schindler went through all the appropriate channels to secure camp prisoners for his own labor force, and he was assured they were going to be moved to Brünnlitz. They weren't, though — 800 men (700 of whom were Jewish) were taken to Gross-Rosen, and 300 women were taken to Auschwitz. They were on his list, and he didn't let them go. It took bribery to secure the release of some, and for others, he promised to pay a daily wage for their freedom. Yad Vashem notes that Schindler's push to secure the freedom of those to whom he had promised safety was the only time such a large group of people were allowed to walk away from an extermination camp while it was still functioning.

His factory was a concentration camp

Schindler saved hundreds of lives with his factory in Brünnlitz, but describing it as a factory is only telling part of the story. According to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, it wasn't as simple as presenting a list of workers needed and transferring them to a factory. First, the factory needed to be classified as a concentration camp.

His original factory, Emalia, was a sub-camp of Plaszow. Even though Emalia was technically only employing about 1,000 workers, Schindler took in another 450 workers from nearby factories to live at his factory instead of Plaszow. When the Emalia workers were forcibly transferred to Plaszow, Schindler relocated the plant to Brünnlitz — and submitted specifications to prove it was eligible for becoming a sub-camp of Gross-Rosen.

The Jewish Virtual Library says that while conditions were infinitely better at Schindler's factories, life was still difficult. No one was beaten, killed, or sent to the death camps, but workers labored in near-freezing conditions and still suffered from regular outbreaks of dysentery and typhus.

The end of the factory, the war, and the Schindler fortune

The Schindlers used and sold everything they owned to help ensure the continued freedom of those in their charge. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, even Emilie's jewelry was sold to buy food and medicine. A section of their factory was turned into a sanatorium and outfitted with black market medical equipment. Those who died were given a proper Jewish burial in a secret cemetery.

At the end of the war, the Schindlers' application to enter the U.S. was denied. After floating around Europe for a few years, Emilie, Oskar, and his mistress ended up in Argentina, where he spent all the money he had been given (by a Jewish organization called Joint) on what Emilie called "small pleasures and objects for which he had not the slightest need... a large part of it with one of his girlfriends."

After a brief attempt at raising chickens and other animals, Schindler left Argentina and his wife in 1957. He never saw either again. Emilie spent the next four decades living alone, and in later years, The Telegraph says she gained recognition for her role in Schindler's operation. While she met countless world leaders, she once remembered that among the most meaningful encounters she ever had was with a fragile woman who had approached her to thank her... "for the chocolate bar that I had given her almost half a century ago."

He died penniless, supported by his Jewish family

According to the Jewish Virtual Library, Schindler not only left his wife in Argentina, but his farm and his mistress, too. Before he died in 1974, he spent some time living in Israel and (via Time) lived out the last years of his life in a one-room apartment in Frankfurt. He never again achieved the pre-war success that had financed his factory, and for most of his life he relied heavily on Jewish charity and donations from those who remembered what he did — and wanted to thank him for it.

After his death, those he saved — and their descendants — continued to care for him. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum says it was a group of those Schindlerjuden who petitioned for and ultimately financed his burial at Mount Zion in Jerusalem. According to Thomas Keneally, he is the only member of the Nazi party to be honored with a burial there.

Remembered as a Nazi and a spy

Oskar Schindler might seem like a likely candidate for being the embodiment of bravery in the face of tyranny, but that's not actually the case — at least, not for some living in his hometown of Svitavy. Radoslav Fikejz was the historian behind an exhibition on Svitavy's most notorious figure, and told DW that he found there was a portion of the population that remembered Schindler differently. "He was a Nazi, a spy, a Sudeten German and a member of the NSDAP, the party that destroyed the republic."

Proving that a small town never forgets, Schindler's less-than-positive image started long before the war, when he was kicked out of school after he was caught falsifying his report card. When the city moved to put up a monument to him near the house that had belonged to his parents, there was massive pushback from the community. The home's owner refused to even put up a plaque marking the spot. According to The Guardian, the story of his rescue of hundreds of Jewish workers wasn't told in his hometown, where his pre-war reputation was still what defined him.

That reputation is also part of the reason his factories — including the one in Brünnlitz, now Brněnec — fell into disrepair, abandonment, and dilapidation. Fortunately, there have also been movements to preserve this section of history.

The memories of Schindler's youngest survivor

The memory of Oskar and Emilie Schindler's work has lived on, in a way more important than even a Steven Spielberg movie: it's lived on in those they saved. In 2013, Leon Leyson — born Leib Lejzon — wrote a memoir called The Boy on the Wooden Box. It told the story of his childhood, shaped by war and his time in Schindler's factory. He was one of the youngest people on the list, only 13 years old when he became No. 289.

Schindler called him "Little Leyson," and he was, indeed, little, says the Independent. The title of his memoir came from the fact that he had to stand on a wooden box to work at the factory, a chapter in his life that came only after years of hiding from the Nazis. He had lived under the irrational, unpredictable eye of Amon Göth before he and his parents were hired by Schindler, who he remembered as a distant but kindly man, writing that he "acted like he cared about us personally."

He was among those liberated in Czechoslovakia at the end of the war, emigrating to the U.S. in 1949. He met Schindler again 20 years later. Leyson, then 35, was afraid he wouldn't be recognized. Schindler, he says, picked him out of a line at the airport and said, "I know who you are. You're little Leyson." Leyson became a veteran of the United States Army and a schoolteacher. Sadly, he passed away just before his memoir was published.