Did Jesus Really Teach His Disciples To Hate Their Families?

Jesus was supposedly all about getting us to love each other — yet in one particularly confusing passage in the New Testament, he tells us to do the exact opposite. In the New International Version of the Bible, the curious line reads "If anyone comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters — yes, even their own life — such a person cannot be my disciple" (NIV 14: 26).

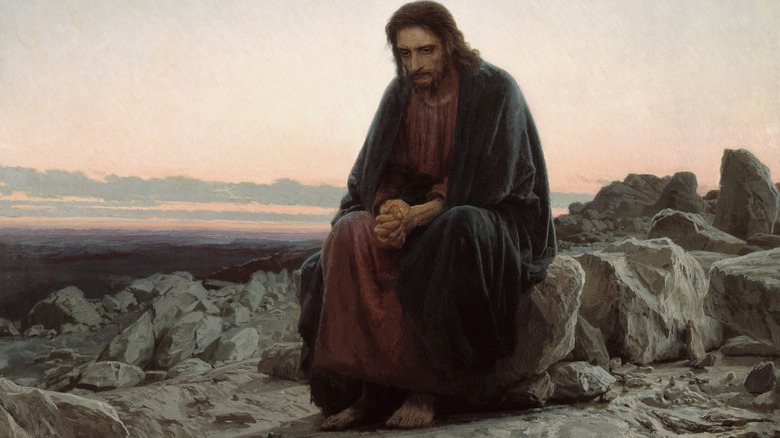

So what gives? The command makes more sense in context, but even then there are multiple ways of interpreting it depending on what you believe. The offending line is part of a much longer passage about the cost of being a disciple in which Christ warns his followers that a life lived with him involves great sacrifices they may not be willing to make — he was arrested and killed after all.

A bit further along in the passage, he underlines his point by saying " ... those of you who do not give up everything you have cannot be my disciples. Still, "hate" is a strong word. Are we supposed to take him literally? Or is it simply a rhetorical device?

The he didn't mean it argument

Many people argue that Jesus' command to hate others was simply a piece of hyperbole and that taking it literally is acting in bad faith. One early version of this interpretation comes from the church father Cyril of Alexandria. In his Commentary on the Gospel of Luke, Sermon CV, in which he wrote that Jesus didn't really mean it when he told his followers to hate others — he just meant that they should love him above all else.

Cyril wrote, "For He demands for Himself our chief affection; and that very justly: for the love of God in those who are perfect in mind has something in it superior both to the honour due to parents, and to the natural affection felt for children." This line of thought is a popular one and it's easy to see why. Jesus talks about love so many times in the New Testament a command to hate others seems out of place.

Furthermore loving them in that order — with Jesus/God coming first — seems to be reiterated in one of the other Gospels, Matthew 22:37. When Jesus is asked what God's greatest commandment is he responds "'Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.' This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is similar: 'Love your neighbor as yourself.'" God is priority number one — no matter how much you love your mom.

What if he really did mean it?

Christians often say that God is love, but the God of the Old Testament is known for being pretty wrathful. There are several instances in which we are told God hates people and things.

Consider Proverbs 6:16-19, "There are six things the Lord hates, seven that are detestable to him: haughty eyes/a lying tongue/hands that shed innocent blood/a heart that devises wicked schemes/feet that are quick to rush into evil/a false witness who pours out lies/and a person who stirs up conflict in the community." The passage is surprising but it's a pretty reasonable list of bad stuff. Slightly harder to understand is Malachi 1, in which we are told God hates a specific person — Esau, "Yet I have loved Jacob, but Esau I have hated, and I have turned his hill country into a wasteland and left his inheritance to the desert jackals. "Hatred is not for God alone either. Ecclesiastes 3 famously tells us "There is a time for everything ... a time to love and a time to hate."

Passages like these seem to indicate that hatred does have a place in our world after all. Theologian Michael J. Wilkins from the C.S. Lewis Institute is among those who make this argument, pointing out that the Bible is actually pretty keen on us hating stuff, and asks us to despise wickedness quite frequently. He concludes that any family member who keeps us from God may actually be worthy of hatred after all.