The Tragic Tale Of Queen Elizabeth II's Cousins, Katherine And Nerissa

Watching television shows — even those that are advertised as being heavily based in reality — with a bit of skepticism is probably a good thing these days. But here's the thing: Sometimes, even the wildest, most unbelievable, and most heartbreaking tales are true. That's the case with one Princess Margaret-centric storyline in "The Crown," and the show only scratched the surface.

While audiences waited impatiently for storylines that involved longtime royal favorite Princess Diana, it was Season 4 that featured one of the strangest stories in recent royal history: That's the tale of Nerissa and Katherine Bowes-Lyon. Who? They're not household names for a good reason, and it turns out that in 1941, the sisters — first cousins of Queen Elizabeth II — were sent to live in a Victorian-era institution that was then called the Royal Earlswood Hospital. Then? They were forgotten about.

The drama that plays out in "The Crown" has Princess Margaret learning about the women, and calling everyone out on the fact that they'd been largely brushed under the rug. And here's where fact and fiction separate a little: Margaret's conversation with the Queen Mother likely didn't happen, but the tragic existence of the sisters isn't just very real, it's shockingly recent. Their story only came to an end with the death of Katherine in 2014, and yes, that's worth saying again: 2014. As is often the case, the truth is actually much, much stranger than fiction.

They were institutionalized in 1941, and declared dead long before they were

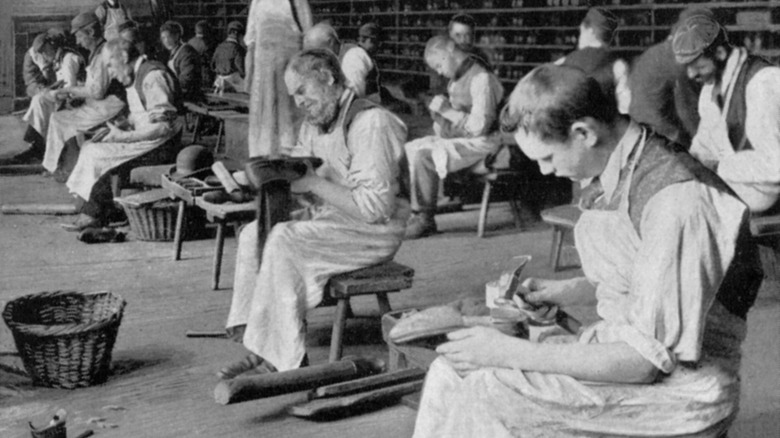

Nerissa and Katherine Bowes-Lyon were born in 1919 and 1926, respectively, to John Herbert Bowes-Lyon. He was the uncle of Queen Elizabeth II, making his two daughters her first cousins. In 1941, the daughters were ousted from their family home in Scotland and sent to Surrey, spending the rest of their lives in the Victorian-era institution (pictured, in 1845). At the time they were committed, they were 15 and 22 years old.

Today, the medical field would term the sisters as developmentally disabled, but that wasn't the case in the 1940s. According to Tatler, their official diagnosis at the time they were committed was to label them "imbeciles," with notes that they were nonverbal and — depending on the source — had an estimated mental age of somewhere between three and six years old.

"Burke's Peerage" prides itself on being the Who's Who of royal families around the world. They've been putting family trees together for a few centuries, but the 1963 edition had what's best described as a whopping mistake: Nerissa, it claimed, had died in 1940, and her sister had died in 1961. When a 1987 investigation by The Sun found that the sisters had been alive all along, editor Harold Brooks-Baker said that they had based their information on what the family said, noting, "If this is what the Bowes-Lyon family told us, then we would have included it in the book. It is not normal to doubt the word of members of the royal family."

No one's sure what happened leading up to their institutionalization

In 2011, Channel 4 ran a documentary called "The Queen's Hidden Cousins," and in their review, The Guardian pointed out that there's some pretty gaping holes in what's known about the cousins — including what prompted Fenella to commit her daughters to a hospital after they had lived at home, with their family, for so many years. It also brought up the question of who had noticed.

A 1987 Thames News report on the sisters and the Royal Earlswood Mental Hospital featured an interview with an administrator, who described Katherine as having difficulty in understanding the world around her, and being "little more than a child." He added that the last family visit she had was in the 1960s, but after that, the only visitors the hospital recorded were volunteers.

Buckingham Palace's response to the story was to issue no real response at all, and according to Vanity Fair, they called the sister's institutionalization and premature death announcements "an issue for the Bowes-Lyon family." The only member of the families associated with Nerissa and Katherine to make a statement was their mother's granddaughter, Lady Elizabeth Anson. She suggested that they had been declared dead by mistake, saying that her grandmother tended to be careless when it came to filling out the paperwork. Those interviewed by the Thames suggested otherwise, saying that those kinds of mistakes just didn't happen... especially considering the information for their siblings had been correct.

[Featured image by Roger W Haworth via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED]

Researchers for The Crown have guessed at how much Elizabeth II and Margaret knew

Annie Sulzberger is the lead researcher for "The Crown," and on the show's official podcast, she spoke about the work that went into the episode with the queen's apparently often-overlooked cousins. She said that one of the first questions that occurred to her was one of the first ones that probably occurred to viewers when they learned about Katherine and Nerissa Bowes-Lyon: How much did the real Elizabeth and Margaret know?

"So we know that they're, I mean, very close in age to Margaret and Elizabeth...," she explained. "It made you think instantly there must've been some understanding of each other that they existed in the world." There were a couple of other big flags, too, including the fact that until they were committed, they lived at Glamis Castle, which she explains was very important to the Queen Mother. That's a bit of an understatement: Glamis is the Queen Mother's ancestral seat, and she was born Lady Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (pictured), to the Lord and Lady Glamis.

Sulzberger also says that she found records of the girls being sent to a school in Hemel Hempstead at some point in the 1930s, and for anyone not familiar with English geography, that's a town that was initially established to relieve pressure from the crowded London. And finally? One of Nerissa and Katherine's sisters joined Margaret in being a bridesmaid for Elizabeth's wedding to Philip.

There's a lot of information that's missing and contradictory

There's a massive problem with researching Queen Elizabeth II's oft-overlooked cousins, and "The Crown" head researcher Annie Sulzberger talked about it on the show's official podcast. She says that although they knew it was something they wanted to touch on (and did, in the episode pictured), there just wasn't that much information out there — even for a team with their access. Although they had the files that had belonged to Nerissa Bowes-Lyon, her sister's files were missing — and what they found in them didn't really clarify things.

"Nerissa is diagnosed 'imbecile,'" Sulzberger explained. "That's the official term. Now, that doesn't kind of equate to anything today. So we had to try to read through records to understand how they described any symptoms of this illness, or physical aspects to it, or was it just mental?"

Sulzberger says that they finally came to the conclusion that neither sister had physical disabilities, but determining exactly what they would be diagnosed with today proved next to impossible. They do say that there was some contradictory information in files, too, that made matters even more complicated when it came time to portray the sisters and cast them respectfully. For example, at the same time it was recorded that they recognized the royal family when they appeared on television, it was also claimed that they only recognized each other as family. and were uncomfortable around others.

The sisters' nurses remembered their one-sided love for the family

A 1987 Thames News report says that the last record they have of a family member coming to visit the sisters was in the 1960s: Still, those who cared for them have shared some heartbreaking stories about their continued devotion to the family that forgot about them. For a 2011 documentary, nurses described the recognition that came when they saw the royal family on television, with one nurse, Onelle Braithwaite, saying (via The Daily Mail), "If the Queen or Queen Mum were ever on television, they'd curtsey — very regal, very low. Obviously, there was some sort of memory. It was so sad. Just think of the life they might have had. They were two lovely sisters."

Another nurse, Dot Penfold, said (via The Sydney Morning Herald), "All the time they were there so far as I was concerned, I didn't ever see anybody visit them — never had birthday cards, never had Christmas cards, not when I was there."

Around the time that the documentary aired, Express claimed to have spoken rather off-the-record to sources close to those in Buckingham Palace. They said that Queen Elizabeth was upset at the idea her cousins had been ignored. It was further claimed that the sisters simply didn't understand who visited them, got upset at the presence of strangers, and regularly received Christmas presents. That was the exact opposite of what former nurse Bridie Tingley had to say: "At Christmas time, they never got a sausage..."

The institution was a groundbreaking but imperfect place

Fast forward to the 21st century, and the world's treatment of mental health concerns and learning disabilities is still far from perfect. Go back a few centuries, and things were downright dire. The hospital that Nerissa and Katherine Bowes-Lyon were sent to was meant to start down the path of rectifying that, and the circa 1855 institution was the first one built specifically for housing those diagnosed with learning disabilities.

Still, good intentions only go so far, and in a 2011 documentary that talked about the sisters' nearly-forgotten lives, some of the nurses who worked there explained that they had been woefully understaffed and overcrowded. They estimated that there were around two nurses to care for about 40 patients, leaving little time for one-on-one care. One explained (via The Telegraph), "You gave them a bath, cut their nails, fed them if they needed help."

One Surrey native recalled going to the hospital to visit her sister in the 1950s. She remembered it as a scary place, saying (via The Daily Mail), "I'd get that gripping feeling of dread." The documentary also shared how much was paid annually for their care: £125.

When the home closed in 1996, Katherine was just moved to another

Exactly what happened to the Royal Earlswood Hospital isn't clear, but when it closed in 1996, one of the queen's two often-overlooked sisters, Katherine Bowes-Lyon, was still living there. (Pictured are Queen Elizabeth and the Queen Mother in 1996.)

According to Esquire, the royal family was consulted about what was going to happen to her, and hospital administrator Peter Kinsey said that they were given the same considerations as other families of the hospital's patients. But Buckingham Palace never apparently released a statement, and Katherine was transferred to another, unnamed facility where she died, almost two decades later. In spite of the exposure, she continued to live in obscurity.

When Annie Sulzberger was trying to find more information on just what happened to Katherine for "The Crown," she shared something surprising on the show's official podcast. She'd discovered that she had been moved into a place that was more of a community setting instead of a hospital one, "but we couldn't really track it down. I tried reaching out to a couple of the nurses who were on their ward, but understandably, I think that they were just a little reticent to speak. So we, we did the best... we could with the information we had."

They weren't the only royal cousins sent away

Nerissa and Katherine Bowes-Lyon were a secret for a long, long time, and it actually didn't stop there. That same year, it was revealed that there were three other cousins who had been similarly committed on precisely the same day as Nerissa and Katherine.

According to a release from United Press International (via the Los Angeles Times), Edonia Elizabeth, Rosemary Jean, and Etheldreda Flavia Fane were also committed to the Royal Earlswood Hospital on that same day in 1941. (They were also featured in "The Crown," pictured.) They were reportedly given diagnoses similar to the labels assigned to Nerissa and Katherine, and they were the daughters of their mother's sister, Harriet. At the time, two of the five women — Nerissa and Rosemary — had passed away.

In 2000, The Guardian publicly wondered why no one had really heard much from Princess Alice in the lead-up to her 99th birthday, and accused the royal family of having a tendency to hide away those who didn't fit the mold. They'd been doing it — particularly with their children — for a long time. They cited the case of Prince John — who would have been Alice's brother-in-law — who was born in 1905, suffered an epileptic seizure in 1909, and was excluded from formal occasions that included his father's 1911 coronation. By the time he was nearing his teenage years, he was sequestered away in Sandringham, where he died in 1919. He hadn't seen his parents in several years.

A pauper's grave

Nerissa Bowes-Lyon passed away in 1986, a year before The Sun would make headlines with their investigation into the sisters' very existence. When she passed, she apparently got no more recognition than she had in life: She was buried in a pauper's grave in Redhill, Surrey's (pictured) Redstone Cemetery, one that was initially marked with a simple plastic stick.

In a 2011 documentary, some of the nurses who cared for the sisters talked about their experiences with them — and at Nerissa's funeral. Nurse Sheila Ruwell said that she was one of the only people there at Nerissa's graveside, and Bridie Tingley added (via The Sydney Morning Herald), "There was no connection with the royalty. That's no credit to them. They could have given her a very lavish funeral. But they didn't, and she had a pauper's grave."

Katherine died in 2014, and she was also buried in Redstone. Her grave marker was a simple wooden cross, and it didn't go unnoticed: A petition on Change.org has asked for the sisters to be given proper grave markers and to have their final resting places cared for, and Nerissa's grave has since been marked with a headstone.

It hasn't gone unnoticed that the Queen Mother has long been a patron of Mencap

The tragic tale of Nerissa and Katherine Bowes-Lyon got a lot of attention when they were featured in an episode of "The Crown," and although Vanity Fair stresses that the episode comes with a lot of embellishment, there's truth there, too: Evidence points to the fact that — as portrayed in the show — the Queen Mother (pictured, in 1971) knew about the sisters from about 1982. At the time she found out about them, she reportedly sent them money "which was used to buy candy and toys."

What she didn't do was visit them, and with a more recent look at the whole messy, sad situation, it hasn't gone unnoticed that the Queen Mother was also a patron for the Royal Society for Mentally Handicapped Children and Adults, which raised some uncomfortable questions about why she hadn't been bothered to set the record straight about her own family.

Buckingham Palace has always been very mum on the sisters, in spite of still being patrons of the same charity. Now called Mencap, the royal family, Buckingham Palace, and the Countess of Wessex held a massive banquet in 2017, to commemorate 70 years of sponsorship. They said that "Mencap has a long Royal history," and lauded a 1963 event in which "Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother, opened Mencap's new hostel and training workshop in Slough." By that time, the sisters were receiving the final visits from their family.