20 Worst Generals Of World War II

By 1939, warfare had experienced dramatic and exponential changes since the end of the First World War. Gone were the days of stationary enemy lines; thanks to technological advancements, World War II ushered in a rapid form of mobile combat never before seen. And grappling with this new-fangled warfare was a generation of military leaders that didn't always get it right.

Indeed, World War II was a completely different mammoth than its predecessor. The global and catastrophic conflict required new and bolder strategies. The rise of tanks and superior aircraft meant armies could cover far greater distances in record time. This meant innovative leadership was needed; generals would need to maintain extended supply lines while committing to swift offensive movements. World War II saw commanders like Dwight D. Eisenhower masterfully balance these categories. However, not all generals could handle this new era of war. Some, while performing well in certain phases of the historic conflict, faltered significantly when pulled out of their element. Others, well, probably should not have been given a position of high command in the first place.

Bernard Montgomery

Historians have often cited Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery's command style as cautious. However, this wary nature was seemingly absent when the British commander crafted Operation Market Garden. In the fall of 1944, after the colossal success of the D-Day landings in June, the German army was on the back foot. To capitalize on this momentum, Montgomery concocted a plan that, according to historians John Buckley and Peter Preston-Hough: "represented an opportunity to deliver the decisive knockout blow to an already reeling Third Reich, and conceivably force a surrender in 1944."

Essentially, the chief objective of Operation Market Garden, which commenced in mid-September, was for Allied forces to take important territory in the Netherlands, such as key bridges. This would allow them direct access across the River Rhine into northern German territory. While Allied troops did take Dutch holdings such as Eindhoven from the Germans, the operation failed in its main objective after ultimately losing the Battle of Arnhem, a city close to the German border and the Rhine.

Overall, Montgomery's plan was too optimistic and doomed to fail. The level of potential German resistance was not given the proper respect and the element of surprise was minimized, as Allied troops were forced to make multiple landings over consecutive days due to the limited availability of aircraft transport. To reinforce British fighting at Arnhem, the Allied troops had to rely on moving up on one narrow road . The wooded terrain surrounding the area also cut Allied radio capabilities. As famed military historian Sir Antony Beevor declared, "Operation Market Garden should never have been launched."

Erwin Rommel

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and his Afrika Korps are frequently lauded to a near-mythical degree for their military prowess, particularly in North Africa. While Rommel's victories, which earned him the moniker of "the Desert Fox," certainly stunned and shocked his Allied foes, historians like Larry H. Addington (via Military Affairs) concluded after the war that even Rommel's greatest achievements in North Africa didn't amount to much in the grand scheme of Axis strategy. In fact, Addington alluded to Rommel's initial North African triumphs as a marvelous success only in the superficial sense. Even at the height of Rommel's success in North Africa, he and his forces were never in the most optimal position, often reliant on captured British supplies and vehicles. Overall, Rommel never showed a true appreciation for the science of logistics.

In his book, "Field Marshal: The Life and Death of Erwin Rommel," Daniel Allen Butler writes that, during his early career fighting in Belgium and France: "Rommel was also too prone to leave his staff and sometimes even his radio vehicle behind while personally directing the actions of a single company or battalion, making effective coordination of the division's armor, infantry, and artillery problematic at best."

A commander of Rommel's caliber should have recognized that communication, or lack thereof, can spell doom for any operation. Even Butler, who frequently defends the German commander against accusations targeting his alleged logistical shortcomings, admits that Rommel could needlessly impede his own momentum by keeping his staff in the dark.

Sebastiano Visconti Prasca

Sebastiano Visconti Prasca is not one of the most well-known World War II generals. However, he should be — if not for any stunning military victory, at least for his incredible incompetence.

In hindsight, Prasca, a commander who was more into working out at the gym than leading his men, was a huge gift to the Allies, as his ineptness helped crumble the Italian invasion of Greece. The Italian general believed the campaign in Greece would be an easy one and urged Benito Mussolini to swiftly act. Prior to the invasion, Prasca made frequent boasts about the state of his men, while completely shrugging off any chances the Greeks had, stating, "the Greek air force does not exist," and "They are not people who like fighting" (via Ian Kershaw's "Fateful Choices: Ten Decisions That Changed The World, 1940-1941").

Well, as history proved, Prasca was wrong. The invasion of Greece was a complete disaster that required German intervention in order to save Axis momentum. As Kershaw notes, Italian forces suffered around 150,000 casualties while Greece suffered closer to 90,000. Prasca was relieved of his command only two weeks into the invasion.

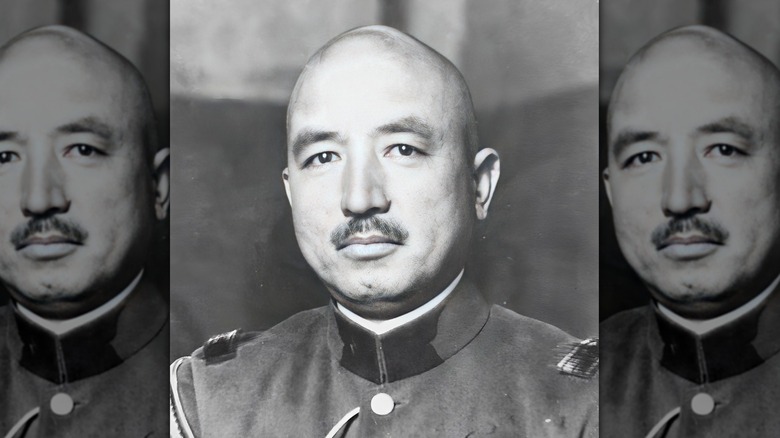

Renya Mutaguchi

Lieutenant General Renya Mutaguchi deserves much more attention from military historians and general World War II buffs, not for his elite-level command but for how incredibly reckless his tactics were.

After securing victory against the British in Singapore in 1942, the Japanese commander Mutaguchi wished to continue his success, this time in India. He believed that if the British could be overcome in Assam — northeastern India — the rest of the subcontinent would soon follow, and even look at his forces as a sort of liberation force from British rule. While Mutaguchi certainly knew how to dream big, he was terrible at planning small. When on the offensive against British opposition in Imphal, he had thousands of his men march great distances while only carrying 20 days' worth of provisions. Mutaguchi believed that if they trekked light, lived off the land, and stole British supplies, speed would be their ultimate ally against the enemy. The Japanese commander also assumed British opposition would immediately crumble at the first sign of pressure and ignored their formidable aircraft capabilities.

These drastic miscalculations proved dire for Japanese forces, who had to contend with invisible foes like starvation and exhaustion before even encountering the enemy. According to Louis Allen's "Burma: The Longest War," in the aftermath of the conflict, Japanese casualties far outweighed those of the British, with the former suffering 54,879 and the latter 12,603. Ultimately, Mutaguchi's leadership proved just as deadly to his men as British bullets. In December 1944, the lieutenant general was called back to Tokyo, relieved of his command, and forced into retirement.

Lloyd Fredendall

The Battle of Kasserine Pass in February 1943 is widely remembered for two things: it was the first clash between American and German forces, and it was the battle where Major General Lloyd Fredendall etched his name in the history books for all the wrong reasons. The American commander, who had a dislike for the British and French, fought alongside his British counterpart Kenneth Anderson when they encountered a very aggressive Erwin Rommel; the two sides met in a devastating clash that saw Allied forces take far greater casualties.

Fredendall, a West Point graduate and veteran of the First World War, completely stunned his superiors with his awful performance. According to multiple accounts, aside from the Allied forces being dispersed too widely from one another in the battle, the multi-national force had no training in fighting as a cohesive unit. Fredendall also botched a prime opportunity to counterattack by delaying the order, giving Rommel's forces time to fall back after already doing heaps of damage. Although Eisenhower couldn't directly place the blame on Fredendall due to the latter's connections, the Allied Supreme Commander still relieved him of command. Fredendall returned to the United States, where he remained for the duration of the war.

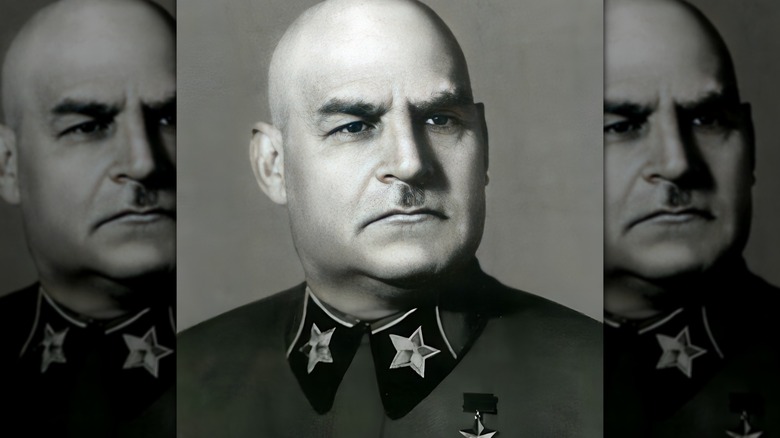

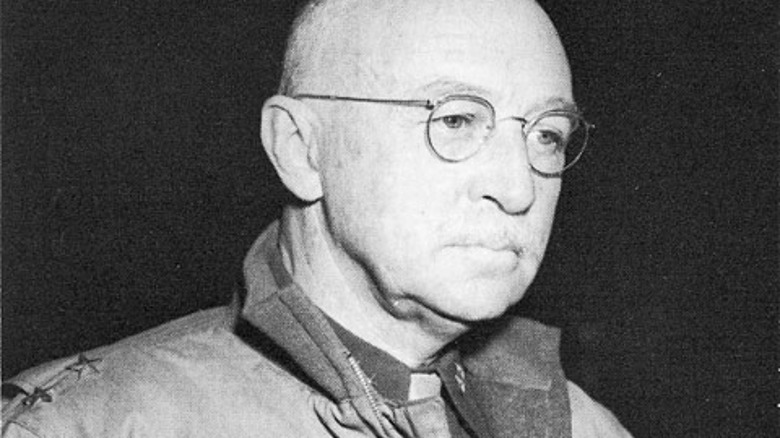

Grigory Kulik

Grigory Ivanovich Kulik's gross arrogance and incompetence were given a historic spotlight when he attempted to lead the initial stages of the Leningrad Front in 1941. Historians agree that his inept command gave way to dire setbacks and serious defeats, and he was swiftly relieved of his command.

Kulik, marshal of the Soviet Union, appears to have been a commander more interested in currying favor with Joseph Stalin than focusing on pragmatic military command and technological innovation. Post-war historians have frequently noted that Kulik spent an absurd amount of energy and time opposing certain mechanized advancements. John Keegan, author of "The Second World War," wrote of the Soviet commander: "[He was a] technological reactionary who opposed the distribution of automatic weapons to soldiers on the grounds that they were incapable of handling them and halted the production of anti-tank and anti-craft guns."

In a period when the Soviet Union would need every advantage they could muster against Nazi Germany, Kulik's actions were detrimental to the Soviet cause. By multiple accounts, he consistently acted as an obstacle against certain technological advancements regarding tanks throughout his military tenure. This is laced with tragic irony, as Soviet armor such as the T-34 proved to be more than capable of giving invading German forces a hellacious time.

[Featured image by Mil.ru via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Rod Keller

Major General Rodney Frederick Leopold Keller, who led the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, may not be one of the most prominent Allied commanders from World War II, but he did take part in D-Day. Sadly, whatever contributions he made were overshadowed by a propensity for drinking and a lack of respect for standard security protocol regarding intel. While Keller's colorful language and gregarious nature made him popular among everyday soldiers, it drove his senior officers up the wall. In his book, "The Generals: The Canadian Army's Senior Commanders in the Second World War," J.L. Granatstein writes of some of the senior officers: "[They] felt he was absent so often visiting his married mistress that the GSO [General Staff Officer] 1 was running the division."

Keller led his forces, around 14,500 Canadian soldiers, during the Normandy landings and fought on Juno Beach. By all accounts, throughout Keller's tenure in France, he failed to impress. He was reportedly always jumpy and appeared only to be interested in his own safety — this led to his senior officers famously claiming that "Keller was yeller" (per "The Generals").

Shortly after D-Day, on August 8, Keller was wounded by friendly fire and replaced. He received no further commands for the duration of the war.

Isamu Cho

The Battle of Okinawa is frequently cited as World War II's bloodiest Pacific engagement, as the Allied victory over the small island led to over 75,000 American casualties. One of the leading commanders who fiercely opposed the Allied landings was Lieutenant General Isamu Chō, a hardline nationalist whose offensive tactics at Okinawa failed drastically.

American forces attacked Okinawa on April 1, 1945. Chō organized the island's defense alongside Colonel Yahara Hiromichi, with the latter preferring a defensive-oriented strategy. However, Chō thought otherwise. Believing the American offensive was vulnerable, the lieutenant general launched a massive attack on May 4 against the American troops against Yahara's warnings. According to Richard Fuller's book, "Shokan: Hirohito's Samurai": "[The offensive was a] complete failure with very losses." By the next day, Chō and his forces were retreating to a different part of the island, but the writing was on the wall. On June 19, knowing the American victory was a certainty, the lieutenant general died by ritual suicide.

What makes Chō's actions so peculiar is that, upon first arriving in Okinawa in 1944, he and Yahara worked together in setting up fortifications and tunnels that could be relied on in a sort of attrition-type strategy. However, just a little over a month after the battle began, Chō completely shifted gears by sending the majority of his forces in a disastrous charge. In hindsight, this makes sense, as one of the first words Fuller uses to describe the commander's personality is "short-tempered" (via "Shokan: Hirohito's Samurai"). Short-tempered indeed.

General MacArthur

General Douglas MacArthur is arguably the most famous U.S. World War II general next to Dwight Eisenhower. However, unlike the latter, MacArthur was not known for being mild-mannered and level-headed. Quite the opposite, by all accounts, MacArthur could be quite the blowhard. For his achievements, the general would boast loudly and proud. But while he never admitted it, he also made mistakes, and they cost many, many lives.

In 1941, MacArthur was given command of the U.S. Army in the Far East. On December 8, several hours after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, they went after another airfield — Clark Field — in the Philippines. Despite having received word of what transpired at Pearl Harbor, MacArthur severely delayed in mobilizing Clark Field's aircraft for a potential offensive. And when the Japanese attacked, the American bombers were still grounded. This was another total victory for the Japanese. The Philippines would eventually be overrun early in the war, with President Franklin Roosevelt ordering MacArthur to leave for Australia. The general left thousands of American and Filipino troops; these troops would then be forced to endure what is now notoriously known as the Bataan Death March.

MacArthur's follies continued throughout the war. In 1944, to support his campaign to take the Philippines back, the Marines were sent to engage the Japanese at Peleliu. The prolonged and bloody engagement lasted months, and saw over 1,000 Americans killed and several thousand wounded. To this day, the battle remains shrouded in tragic controversy as, in the end, Peleliu didn't really factor into MacArthur's grand plans for the Philippines.

Maxime Weygand

In May of 1940, France was not in the greatest position. The German Blitzkrieg had launched its tanks and heavy armor through the Ardennes Forest and were closing in on Paris. To shore up the defenses of a quickly deteriorating situation, the French government brought in World War I veteran and military commander Maxime Weygand. Unfortunately for the Allies, this turned out to be oil on an already raging inferno.

As if the situation in France wasn't bad enough, with Hitler's forces rapidly nearing the capital, Weygand managed to find ways to make everything worse. On the morning of May 19, the French command ordered troops fighting in Belgium to come down to meet the attacking Germans. That evening, Weygand was given command, and one of the first things he did was to cancel that counterattack. After conferring with other Allied commanders for three days, Weygand committed to the same exact plan that was made before. This gave German infantry a tremendous opportunity to catch up with its rapidly moving heavy armor and close any gaps in its offensive.

Paris fell on June 14, 1940 and an official armistice was signed with Germany on June 22. In July 1939, Weygand had declared, "The French army is stronger than ever before in its history; its equipment is the best, its fortifications are first-rate; its morale excellent, and it has an outstanding High Command. Nobody wants war but if we are forced to win a new victory then we will win it" (per "Blitzkrieg: Myth, Reality, and Hitler's Lightning War: France 1940").

Maurice Gamelin

Less than a year after invading Poland, Germany launched a campaign against France and the Low Countries (Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Belgium). The offensive was fierce, rapid, well-coordinated, and succeeded in just over six weeks. General Maurice Gustave Gamelin, France's commander-in-chief, took little action to stop it. Or rather, every action he did take worked in the enemy's favor.

In his book, "Servir," which was published after the war, Gamelin expressed that, should Poland be swiftly defeated: "[France] could not hope for victory except in a long war. It had always been my opinion that we should not be able to assume the offensive in less than about two years ... that is, in 1941-42" (per William Shirer's "The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich"). This passivity allowed the Germans to take the initiative at too many critical junctures.

Dr. Richard J. Shuster, historian and professor at the U.S. Naval War College, notes (via Marine Corps University) that Gamelin's planning — and the planning of Allied command overall — for the initial stages of the Western Front were grossly inadequate. Gamelin put too much emphasis on defense and lacked contingencies should his first plans fail; he and his Allied contemporaries prepared for a prolonged and cagey engagement reminiscent of World War I's stationary nature. The French commander predicted that Belgium would be the enemy's initial focus and placed his best troops there, but left the Ardennes Forest undefended. The Germans unleashed a motorized offensive through the forest, outflanking Gamlin's prized Maginot Line, catching the Allies, and the world, off guard.

Arthur Percival

In February 1942, the Japanese military scored a massive victory in the Malay peninsula when they defeated Commonwealth troops stationed in Singapore, capturing the city and delivering a tremendous blow to the Allied Pacific war effort in the process. Despite boasting a significant numerical advantage (85,000 men) against the Japanese offensive (35,000), British forces were overwhelmed and surrendered within days. At the helm of this historic defeat was Lieutenant-General Arthur Ernest Percival.

As Japan continued to expand its reach during the onset of the war, there was a contemporary belief in Great Britain that Singapore was an impregnable stronghold. However, this conviction was severely misplaced. For starters, Singapore had long gone without proper defense funding. And, while equipped with more troops, the British forces were not nearly as experienced as their enemy, nor had as many tanks and superior aircraft. While Percival demanded more resources be brought to Singapore before the Japanese attack, and showed the tactical acumen that the British standing in Singapore was not as secure as initially believed, the Lieutenant-General's overall leadership proved to do more harm than good.

Under Percival's leadership, bitter relationships between subordinate commanders ran rampant, leading to poor communication between the Commonwealth's multi-ethnic army. Furthermore, the Lieutenant-General also placed his soldiers throughout the entire Malayan Peninsula. This decision nullified Percival's main advantage — number superiority — as it allowed Japanese troops to outnumber their enemy at various landing zones. This error was replicated again when Japanese forces reached Singapore Island itself. The disastrous defeat at Singapore led to terrible Allied casualties and thousands of Commonwealth soldiers being taken as prisoners, with many not surviving Japanese captivity.

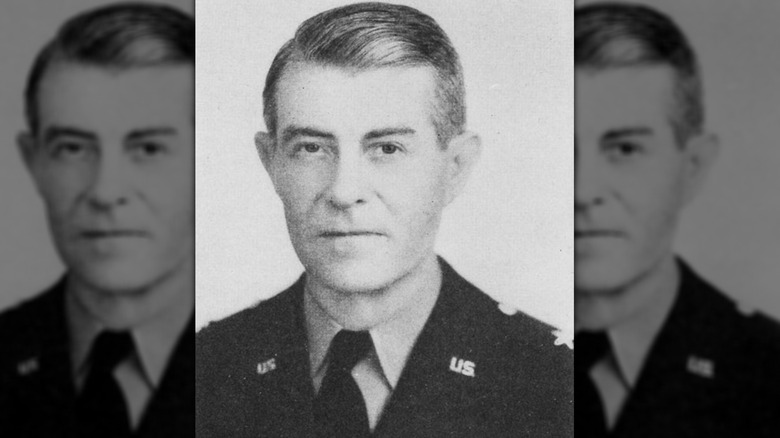

Jay MacKelvie

There are few stranger instances when it comes to World War II generals performing poorly in the field than the curious case of Brigadier General Jay MacKelvie. A veteran of the First World War, MacKelvie rose to prominence shortly before D-Day, when he was put in command of the 90th Infantry Division. However, by all accounts, he quickly proved to be unfit for such a position. MacKelvie became known for being a little too much of a statistics-obsessed protocol purist upon receiving his promotion, while neglecting his troops' combat readiness.

In June 1944, when the Normandy Landings commenced, MacKelvie and his men's own lack of battle preparedness quickly became evident. According to James Holland's book, "Normandy '44: D-Day and the Epic 77-Day Battle for France," the general and his division made such little progress against German opposition that his superior — General J. Lawton Collins — went to the front to investigate. Collins was shocked at the timidity displayed by the men of the 90th and the complete lack of fighting overall. When he pressed MacKelvie for an explanation, he was met with an honest lack of answers.

It's been said that the division's assistant commander – Samuel Tankersley Williams – found MacKelvie hurled up in a ditch instead of fighting. "Goddamn it, General, you can't lead this division hiding in that goddamn hole," Williams reportedly yelled (via The Atlantic). In a time when German resistance was at its zenith, MacKelvie's indecisive leadership was the last thing the Allies needed; he saw combat only for four days, before being relieved of command and transferred.

Rodolfo Graziani

When you combine horrific brutality with simple ineptness in tactics and strategy, one ends up with a general like Rodolfo Graziani. The Italian commander's name forever lives in infamy for the many atrocities he committed against civilians in Libya and Ethiopia. But when engaging other standing armies, Graziani never appeared to show the same aggression he did against non-combatants.

After his campaigns in Libya and Ethiopia, Graziani battled the British in Egypt, where he would suffer his greatest defeats. An initial and firm believer in embracing mechanized warfare during his time in Ethiopia, Graziani strangely moved away from this belief during his time in Egypt. Indeed, Graziani's entry into the region in September 1940 was a slow one. British troops may have been forced into a much more precarious position if the Italian commander had entered the country a little less cautious. Instead, Graziani's wary approach allowed his enemy to gain some more time to prepare and for Allied resources to flow.

Operation Compass was the final nail in the coffin of the Italian general's military career. A British armored offensive, planned by Sir Richard O'Conner, struck at Italian positions on December 9, 1940. (Famously, Graziani's forces did little to protect a 15-mile gap in its defensive line). Graziani's men were quickly overwhelmed; within days, over 30,000 of his men were routed and taken prisoner. Despite boasting a significant numerical advantage of around 150,000 men, Graziani's command failed against the more mobile and smaller British attack by around 30,000 men.

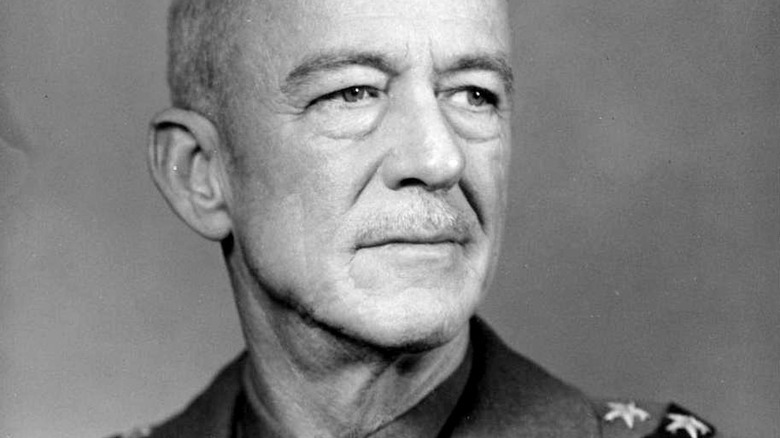

Mark Clark

Mark Clark is one of the most controversial American generals to have served in World War II. In his book, "Marshall and His Generals: U.S. Army Commanders in World War II," Stephen R. Taaffe touches on his reputation as a glory hogger: "He craved the limelight and was a shameless self-promoter, often at the expense of others. His temper, vanity, chauvinism, and aloofness toward subordinates worked against him too, so that more than one officer later called Clark his own worst enemy." This often hampered Clark's relationships with other commanders, especially British ones, whom he served alongside with in Italy.

In January 1944, Clark ordered the crossing of the Rapido River despite immense reservations from his subordinates. German resistance was heavy, and the attempted crossings failed, leading to over 1,000 casualties for the 36th Division. After the war, the men of the 36th would request an official congressional investigation into Clark's folly.

One of Clark's most controversial actions, however, came in June 1944, when he successfully took Rome. While this was certainly a prestigious moment, as the city was the first Axis capital to fall during the war, the actual strategic value of taking Rome at that time has long been scrutinized. This is primarily because Clark's actions directly went against the orders of his superior, General Harold Alexander. The Italian campaign was already long and arduous, and miscommunication among commanders was not an obstacle that Allied forces needed on the peninsula. Alexander's initial plans were for Clark to halt the retreating German 10th Army at Valmontone — nearly 30 miles from Rome. Clark's detractors have long lambasted him for instead going after the more prestigious target.

Lev Mekhlis

Lev Mekhlis was a Soviet commander who proved to be more adept at assisting Stalin with purges than he was at carrying out effective military results. In early 1942, the army commissar was sent to Crimea during the German invasion of the Soviet Union.

According to David M. Glantz, author of "When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler," Mekhlis was a hostile presence toward his own comrades: "Mekhlis openly bullied commanders and reshuffled personnel." John Erickson, author of "Stalin's War with Germany," also notes Mekhlis' constant need "to worry the life out of every commander by his incessant day-and-night queries." During the Battle of the Kerch Peninsula, Mekhlis' involvement indeed proved to be a boon for the Germans. Mekhlis, aspiring for some great majestic offensive, made strange directives such as banning the digging of trenches. Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, leading the German offensive in Kerch, carved through Soviet resistance and proved to be far too much for Mekhlis. Mekhlis, ever the politician, was quick to try to protect his image and deflect blame to other commanders by writing to Stalin. Instead of obtaining support from his old friend, Mekhils instead received sharp and scathing reminders of his responsibilities.

In the end, the five-month Kerch campaign was a Soviet disaster. In May alone, the Soviets lost an estimated 170,000 troops. Mekhlis' leadership, by all accounts, proved to have been nothing more than a dire detriment. After Crimea, he was swiftly demoted and relieved.

Courtney Hodges

The Battle of Hürtgen Forest was a brutal and bloody back-and-forth confrontation between American and German forces. The fighting, which began in September 1944 and lasted nearly five months, was so fierce that American soldiers dubbed the area the "Death Factory. Tragically, the nickname was more than fitting; American forces suffered nearly 34,000 casualties by the end of the battle. To make matters worse, multiple historians have since claimed that the bloody affair should not have even happened, and that the forest itself offered little to no strategic value. At the tactical helm of this calamity was Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges.

By the fall of 1944, Hodges, commander of the First Army, shared in widespread Allied optimism before the battle: "Given ten good days of weather the war might well be over as far as organized resistance was concerned" (per U.S Army CGSC). As history proved, good weather proved rarer than gold, and the war did not end at Christmas. As a commander, Hodges fumbled by delegating much of his duties to his chief of staff; he also had the harsh reputation of too often dismissing subordinate commanders, and rarely visiting troops at the front lines.

During the Battle of Hürtgen Forest, Hodges sent scores of men into an unforgiving terrain, knowing they'd receive little air or armored support. The forest swallowed up valuable American manpower and bogged troops down for almost half a year. Military historian and Hürtgen veteran Charles B. MacDonald summarized the chaotic situation simply: "[A] misconceived and basically fruitless battle that should have been avoided" (per Robin Neillands' "The Battle for the Rhine").

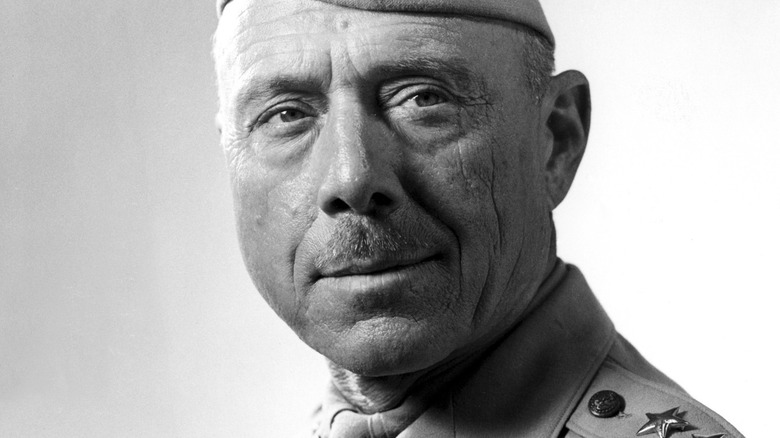

Kliment Voroshilov

Kliment Voroshilov, an old friend of Stalin, was a military commander whose leadership did little to help the Soviet cause during the Second World War. Despite a terrible outing during the Finnish-Soviet War (1939-1940), Stalin gave his comrade one more chance in July 1941, when he assigned Voroshilov to helm the Leningrad defense.

While multiple accounts do recognize Voroshilov for displaying immense valor during the fighting around Leningrad, his actual tactics left much to be desired. Frankly, it's difficult to discern what Voroshilov's tactics actually were in the first place. Roy Medvedev, author of "All Stalin's Men," highlights Voroshilov's ineptness by pointing out what little he did to halt German forces from encircling Leningrad. "Voroshilov acted bravely but incompetently. He had plenty of nerve and often drove out to the front line of the defense, squarely in the enemy's view. What he lacked was firmness in his command of the troops. At the end of August Leningrad was virtually surrounded." Voroshilov's incompetence ran far and wide to the point that he failed to notify Stalin of a nearby town (Shlisselburg) getting captured; the Soviet leader discovered this news by reading a German communiqué.

Medvedev's account cites a blundering marine offensive led by Voroshilov the day he was being relieved, a desperate act for a desperate cog in the imperious Soviet system. Overall, Voroshilov's counterattack planning earned him ridicule from his peers. The commander found himself swiftly replaced by the far more talented Georgy Zhukov, who made it a point to ignore any attempt at advice from Voroshilov.

John P. Lucas

John P. Lucas was an American general tasked with establishing an Allied beachhead near Rome. Filled with immense reservations from the very start — the commander was uncertain what the endgame goals were on the Italian peninsula, and he was given limited resources and troops to complete his task — Lucas was surprised to find little to no resistance upon the initial landing at Anzio on January 22. The operation — titled "Shingle" – caught the German army with their backs turned. According to Stephen R. Taaffe, author of "Marshall and His Generals: U.S. Army Commanders in World War II": "By the end of the day Lucas had 36,000 troops ashore. There were in fact almost no Germans between Anzio and Rome, presenting Lucas with the opportunity to seize the Italian capital. Instead, Lucas followed his instincts and his interpretation of his ambiguous orders by instructing his men to dig in along a defensive perimeter."

This cautious attitude proved to be a costly one. Had Lucas taken the initiative, he and his men could have marched forward and caught an unorganized and unprepared German force. However, because he lingered and focused his efforts on defense, the Germans had time to regroup and prepare. This turned the Battle of Anzio into a bitter firefight lasting until June, leading to thousands of Allied casualties.

The Anzio stalemate, and Lucas' efforts, have long received derision, with the most famous criticism coming from Winston Churchill. "I had hoped we were hurling a wildcat into the shore, but all we got was a stranded whale" (via "Marshall and His Generals").

William H. Rupertus

The Battle of Peleliu is possibly one of the most tragic military engagements in World War II history for the reason that it may have been completely unnecessary. While blame can certainly be assigned to the top brass, fault at the tactical level must be given to General William H. Rupertus. Rupertus expressed immense confidence before the offensive against Peleliu started, and believed Japanese forces on the island would be defeated in mere days. However, the campaign lasted over two months. Rupertus, a marine through and through, allowed his pride to blind him and balked at the idea of needing army troops, and did little to quell the bitter rivalry between his joint force.

According to Bill D. Ross, author of "Peleliu: Tragic Triumph: The Untold Story of the Pacific War's Forgotten Battle," Rupertus didn't show the greatest interest in the training issues his men encountered during the preparation phases, which became a terrible logistical quagmire. Despite this, Rupertus' misplaced optimism seemed unwavering. J.A. Isley, a military historian and Princeton University professor, later summarized things perfectly regarding the constant mishaps that plagued the operation from the beginning. "Thoughtful observers might well regard these unhappy incidents as harbingers of calamities yet to come" (per "Peleliu: Tragic Triumph").

In the end, the American forces found victory, but not without cost. The Battle of Peleliu proved to be a bloody and lamentable confrontation; according to the Marine Corps University, over 1,300 marines were killed, and 5,400 wounded.