Common Myths About The First World War

World War I is part of the national history of many countries today. The incredible scale of the Great War meant it touched countless lives across the world, from the U.K. to the South Pacific. As a result, plenty of us have our own family stories about the war and view it in a uniquely sentimental light.

The deeply personal nature of the first World War means it still elicits powerful emotional reactions from us today — emotions that sometimes obscure the truth about what the war was really like. The political happenings behind the conflict have often been misunderstood or forgotten, and many oft-repeated details about the war are tired exaggerations.

Our view of the war has also been heavily shaped by mawkish films and TV shows that typically depict only one side of the conflict — the war along the Western Front fought in the trenches. In reality, World War I was more complicated, more varied, and involved far more people from around the world.

Myth: The U.S was completely neutral until 1917

While it is true that America was neutral on paper, in reality, they were always more closely aligned with the Allied Powers (Britain, France, and Russia). Before the U.S. signed up to fight, many Americans joined the French Foreign Legion so they could enter the war regardless of what the nation said or did (via History). Others created a volunteer ambulance service in Paris and sent food aid to bullied Belgium, according to The World War One Centennial Commission. German atrocities got very bad press in the U.S. throughout the war, swinging public opinion toward the Allies (aka the Entente).

President Woodrow Wilson's neutral stance was an important part of his campaign, and he famously proclaimed that the U.S. "must be neutral in fact as well as in name." But America's announcement of neutrality hardly mattered because the U.S. ended up bankrolling the Allies anyway.

The choice to give more money and arms to Britain and France than to the Central Powers (or the Triple Alliance), was not deliberate in the beginning — the British naval blockade made it difficult for America to trade with Germany, and some Americans were even outraged it had compromised their neutrality. Nonetheless, Wall Street bankers like J.P. Morgan ended up furnishing Britain with enormous loans, which unintentionally made the U.S. a crucial ally for Britain. While the blockade continued, a steady stream of American-made goods and guns increasingly made their way into the Allies' hands.

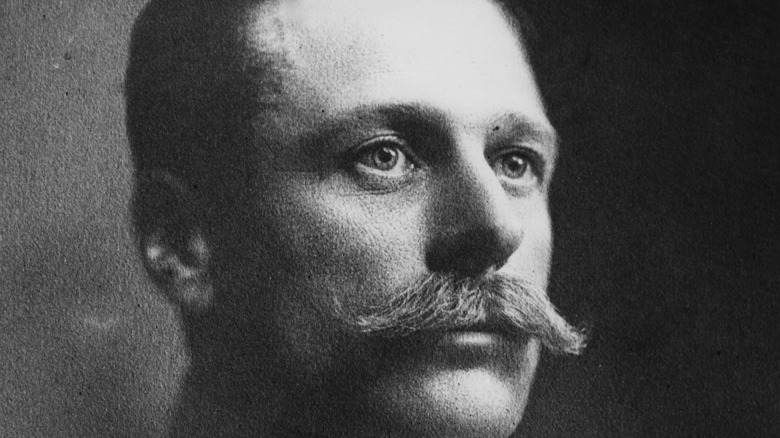

Myth: The Allied generals were incompetent buffoons

Particularly in the U.K., big-name World War I generals are often associated with incompetence, cowardice, and cruelty. People imagine military leaders told soldiers to walk unprotected into machine gun fire without thinking it through (via the BBC). While it's true that some battles were ineptly fought — such as the battles of Somme and Passchendaele — in general, the Allied commanders thought a great deal about how to avoid enormous slaughter.

The speed of changing technology, not stupidity, should be blamed for the horrifyingly high death tolls of World War I. Both sides began using artillery and machine guns on a huge scale for the first time. At the beginning of the war, it wasn't obvious what either side could do about it. The new technology ground the conflict to a bloody halt and made crossing no man's land nigh on impossible. Old-fashioned tactics such as cavalry charges suddenly became obsolete (per the British Library).

Generals like Britain's Field Marshal Douglas Haig encouraged radical technological and tactical changes to surmount these problems, and over four years, warfare changed forever. Tanks and planes were tested and perfected, and artillery became more accurate and deadly. Toward the end of the war, the Allies began winning scores of battles thanks to their willingness to innovate.

Finally, it should not be forgotten that many generals fought on the front lines, rather than lounging miles away. Roughly 18% of Britain's generals were wounded or killed in battle (via History Hit).

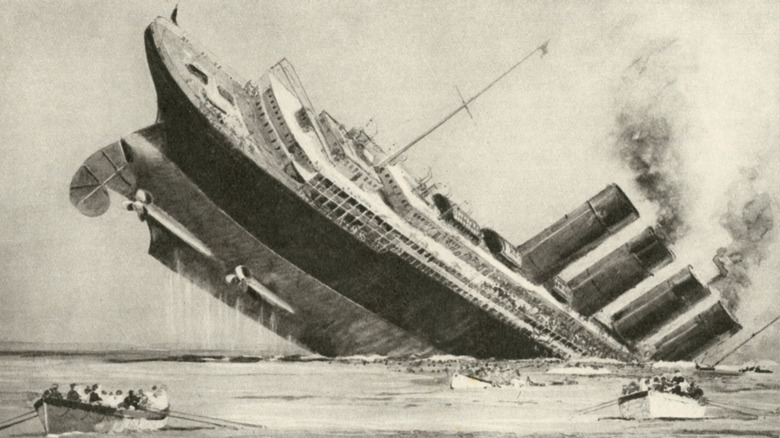

Myth: The sinking of the Lusitania got the US involved

There is a common misconception that the Lusitania disaster was a breaking point for the U.S., causing them to enter the war. In reality, although the attack on the Lusitania caused outrage, it was sunk by the Germans several years before the U.S. joined the conflict and was just one of many events that contributed to the final decision (via History).

A second, less well-known sinking actually brought the U.S. even closer to war. In 1916, the Germans blew up the Sussex ocean liner in the English Channel, killing many on board and causing a temporary crisis, according to the U.S. Department of State. Even then, President Woodrow Wilson managed to negotiate with the Germans to maintain diplomatic relations. Wilson continued to hold off even when Germany began recklessly attacking naval traffic again in 1917.

The final straw arrived in the form of the Zimmerman telegram in February 1917 (via the History Press). This secret communication was intercepted by the British secret service and provided evidence that, despite attempts to maintain the peace, Germany was an existential threat to the U.S. In the letter, Germany offered to back Mexico if they attacked America, urging them to reclaim large swaths of the American South. To the delight of the beleaguered British, the contents of the telegram deeply shocked Americans. The U.S. declared war less than a month after the news reached American papers.

Myth: World War I was the first global war

Although we call it the first world war, it actually wasn't. World War I was originally called the Great War, and there is a good case to be made that at least four world wars have taken place in the last three centuries (via the BBC).

The real first world war was arguably the Seven Years' War (aka, the French and Indian War). Just like in World War I, European colonies were dragged into a monumental showdown between France, Britain, Spain, and a host of other European nations. The war spread across Europe, the Caribbean, North America, and India, laying waste to populations who really had no vested interest in the fighting, according to the National Army Museum.

In the late 18th century, Napoleon also started a world war that involved almost every nation in Europe, and helped spark the North American War of 1812. The conflict spilled over into Ottoman colonies in the Middle East, such as Egypt and Syria, while the great powers chased each other across the globe (via History). Although neither the Seven Years' War nor the Napoleonic Wars beat World War I in terms of scale, their impact on global history should not be underestimated.

Myth: People were enthusiastic about signing up for World War I when it began

This myth exists in many countries and is mainly down to wartime propaganda and censorship. Although everyone was keen to project a united front, there were widespread protests against the war across the globe.

In Britain, this myth stems from the fact the army was originally populated by enthusiastic volunteers. At the beginning of the war, Britain's enormous empire made it possible to avoid implementing a draft, and the cheerful recruits who signed up became a symbol of gung-ho enthusiasm for the war (via the Open University). However, even before conscription was introduced, large sections of society voiced their objections to a conflict that made little sense to them. London was host to anti-war demonstrations, particularly from left-wing groups and trade unions who used strikes to voice their discontent.

In the U.S., on the other hand, draconian measures were implemented with lightning speed to silence any objections to the war. Around 2,000 Americans were arrested under the Espionage and Sedition acts, which criminalized anything that could be categorized as unpatriotic dissent (via History). Printed materials that criticized U.S. involvement in the war were banned altogether, creating the illusion of a unified nation. As in the U.K., socialist groups were often staunchly against the war, and they were joined by people from all walks of life, including some prominent businessmen such as Andrew Carnegie (via Washington University).

Myth: The war was mostly fought by Europeans and Americans

The protagonists in most blockbuster World War I films, such as "1917", "All Quiet on the Western Front", and "Paths of Glory," are uniformly white, either Europeans or Americans. However, millions of non-Europeans were also enlisted to fight the war to end all wars.

Roughly 100 countries were involved in the war to some degree, largely thanks to colonialism (via Thoughtco). The biggest single contribution from a colony on the Allied side came from British India, which supplied over 1 million Indian soldiers and civilians, according to the British Library. Although they are scarcely remembered today, thousands of soldiers were awarded a warm greeting in France at the time with cheers of "Vivent les Hindous," and quite a few Indian soldiers won Britain's highest honor for valour, the Victoria Cross.

A further 2.5 million soldiers were called up from all over Africa by both sides, and around 10,000 Jamaican soldiers signed up, along with citizens from around the Caribbean (via the National Army Museum). A host of other nations that seemingly had no reason to get involved also showed their support in various forms. Toward the end of the war, Thailand (then Siam) sent 1,300 pilots and mechanics to the Allies and Brazil declared war on Germany.

Myth: The war was fought almost exclusively in Europe

When you think of World War I, you probably think of trench warfare along the Western Front, but many other regions saw pitched battles as well, some of which are more well-known than others.

For example, an incredible amount of fighting took place in Africa (via the British Library). The British and French invaded Togo (a former German colony then known as Togoland), fought pitched battles in Cameroon, and had several standoffs in Mozambique and the Congo. South Africa was heavily involved on the Allied side and did their best to drive out its German neighbors. By the end of the war, almost 45,000 Kenyan soldiers had died fighting for the British, yet their sacrifice is rarely remembered.

Many smaller battlers also occurred in some unlikely places. In late 1914, for example, a major battle took place in China because the city of Tsingtao was under German colonial control, according to the British Library. The ensuing fight ended in an Allied victory after British and Japanese troops assaulted the city. Similarly, to the south and east, Australia and Japan scrambled to pick up German colonies that were scattered across the South Pacific (via the South East Asia Museum). The South Pacific war is known as the "neglected war," though it resulted in a number of momentous invasions, including the Australian occupation of Papua New Guinea.

Myth: Tanks ended the war

The invention of the tank was one of the great military innovations of World War I, but it did not win the war. At times, tanks were used to great effect, able to cross no man's land and roll over barbed wire. However, many early experiments using tanks were also pretty laughable, and they by no means secured the Allies' victory.

The first time the British used tanks in the war was actually at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, one of Britain's most disastrous engagements (via the Canadian War Museum). The Allies won the battle following terrible losses, but the tanks did not provide much help. These early tanks were extremely slow — men could easily outrun them — and they could be dispatched with a well-aimed shot to the fuel tank, according to History Hit.

Tanks were a real work in progress, and many test vehicles came to a grinding halt on the battlefield or were blown up by artillery (via BBC). The tank did rapidly improve during the war, and they helped to win a few battles including the famous Battle of Cambrai in 1917. However, for the most part, the Allies just didn't have that many of them anyway and were forced to win a string of victories totally tankless.

Myth: The two sides played soccer on Christmas day

This story is a half-truth — there is evidence several small soccer games may have occurred, but it was not a massive event. The oft-repeated legend holds that the Germans and the British laid down their guns on Christmas Day to play friendly soccer matches in no man's land. While it would be nice if this inspiring tale was truthful, only two small matches have been confirmed (via History Extra).

The myth that British soldiers left the trenches en masse to play the Germans emerged because rumors about soccer matches spread like wildfire among the ranks in 1914, according to the New Republic. Although these rumors were largely unsubstantiated, many stories were printed in various newspapers secondhand. In fact, there is more evidence that the Brits asked the Germans to play and the Germans said no. One soldier wrote in his letters that his unit "... asked the Germans to send a team to play us; but either they considered the ground too hard, as it was freezing all night, and was a plowed field, or else their officers put the bar up."

On the upside, the truth about the truce is actually slightly more interesting. British and German soldiers really did meet up on Christmas Day to shake hands, exchange souvenirs, and take photographs together (via The Conversation). They just didn't spend a lot of time playing football.

Myth: The war ended at 11 a.m. on November 11, 1918

World War I is often said to have ended on November 11, 1918, at 11 a.m., although the treaty of Versailles was actually signed in June of the following year (via History). While that fateful day in November was indeed the end of the war for many people, not everybody got the message, and some people would not go home for years.

When the armistice was agreed upon, Allied soldiers fighting the East Africa campaign were in search of a German commander, Major General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, and they had no easy way of informing him and his troops that the war was actually over (via Gov). Lettow-Vorbeck kept fighting until he found out about the armistice the following day, November 12, and he only surrendered on November 25.

Smaller wars prompted by the first World War also continued for many years after the main conflict ceased. Foremost among them was the Civil War in Russia that had arisen in 1917 (via the Imperial War Museum). Allied troops stationed in Russia sided with the Tsarist Whites, and sadly they were forced to remain in the country and keep fighting when everyone else went home. Similarly, in the Balkans and Turkey, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire was not quite complete. The peace deal brokered by the Allies proved unacceptable to the Ottomans, who continued to fight the Greeks from 1919 until 1923.

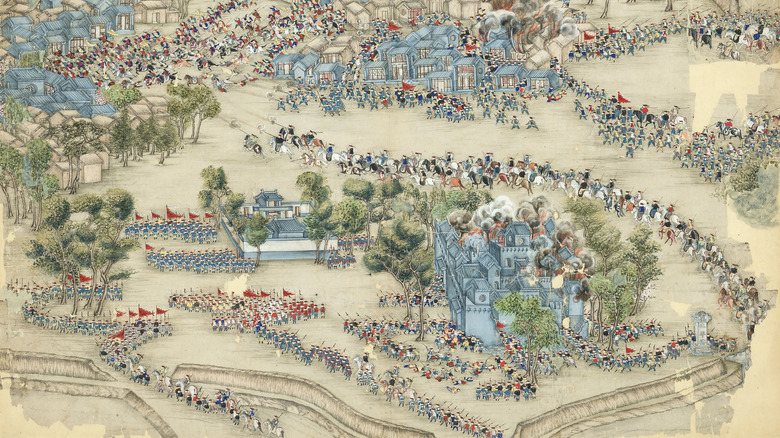

Myth: World War I had the highest death toll of any war at the time

Roughly 20 million people were killed in World War I, a conflict in which new technology was tested against human flesh (via the Robert Schuman European Centre). An additional 21 million were also injured and traumatized. However, despite popular belief to the contrary, it was not the deadliest war in history at that time. Prior to World War II, the deadliest war in world history took place in China.

China's enormous size coupled with its history of civil strife has resulted in some eyewatering death tolls. For example, the Taiping Rebellion, which took place during the 19th century, claimed somewhere between 20 and 70 million souls, depending on which estimates you trust (via History). The conflict split China in half and carried on for 14 agonizing years. On the other hand, the An Lushan Rebellion in 8th-century China took around 36 million lives in just eight years (via WeekinChina). Both wars matched or surpassed World War One's death toll without the use of mechanized weapons.