The Untold Truth Of Brigham Young

Latter-day Saints leader Brigham Young was a quintessential 19th-century American, enamored with the ideals of personal and political liberty, religious freedom, and the potential to forge his own destiny – which he claimed the federal government was infringing upon. He loved America, her Constitution, and her system. True to his Puritan New England roots, he sought to create a new Zion, a "city upon a hill" in Utah – recalling early American settlers.

Many of his opinions are, of course, completely odious by modern standards, but they were the products of his time, and, in some cases, reflect a nuance that was so often missing in the emotionally charged debates of the 19th century.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (colloquially known as Mormonism) reveres him as a leader, prophet, and visionary. Outsiders have reviled him as a racist charlatan, adulterer, and anti-American theocrat. Here is the fascinating, untold story of Brigham Young that made him such a divisive yet monumental figure in American lore.

His leadership led to America's Mormon kingdom

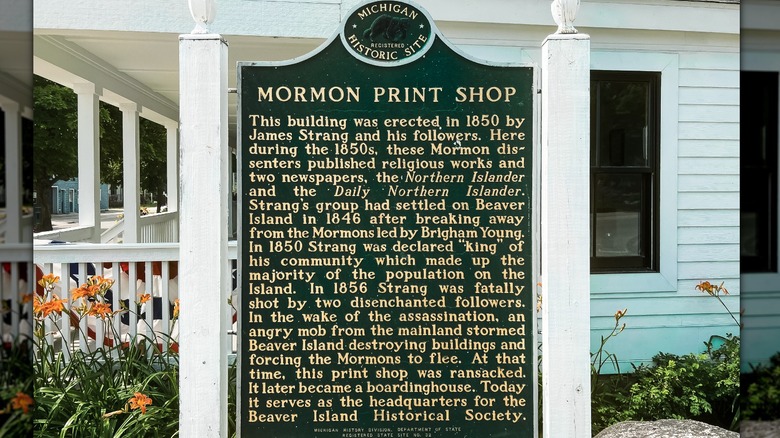

After Joseph Smith, the founder of the Latter-day Saints, was killed in 1844, Brigham Young, as head of the religion's Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, succeeded him as leader. But Young faced opposition from Wisconsin lawyer James Strang, who claimed Smith and an angel had both tapped him to lead the church over Young. Strang was a strange man with delusions of royal grandeur, as evidenced by his diary. In one telling entry, he wrote: "I have spent the day in trying to contrive some plan of obtaining in marriage the heir to the English Crown. It is a difficult business for me, but I shall try if there is the least chance. My mind has always been filled with dreams of royalty and power."

When Young became head of the church, Strang took his followers to Beaver Island, located off the northwest coast of Michigan's Lower Peninsula, to make his regal dreams a reality. There, he established a timber community that also engaged in piracy and robbery against Beaver Island's non-LDS and mainland coastal settlements. According to an account in "A Child of the Sea," by their Beaver Island neighbor Elizabeth Whitney, divine revelation permitted Strang and his followers to rob non-LDS locals and whip their co-religionists who tattled to the authorities.

In 1850, Strang was invested as "king" in a farcical ceremony with a cardboard crown. This declaration of sovereignty, and his other illegal activities, landed him in federal court on treason charges. He was acquitted, elected twice to the Michigan legislature, and eventually shot dead by his own men in 1856. His "kingdom" died with him.

He helped establish Catholicism in Utah

Although the Latter-day Saints' Church was stereotyped as unable to live alongside other faiths, Brigham Young had a cordial relationship with Catholicism, according to the Utah Historical Society. Young's admiration for Catholicism was pretty shocking, especially when American anti-Catholicism was at its height.

There are two stories of how Young helped establish Catholicism in Utah. The first tells that Fr. Edward Kelly, tasked with establishing a permanent Catholic presence in Utah, wanted to build a school on disputed land. Brigham Young, who ran Utah behind the scenes, engineered a court ruling in Kelly's favor and reportedly donated $500 to the Catholic school.

The other account, per the Catholic Quarterly Review, recounts that nuns visited Young's house to lobby for a Catholic church in Salt Lake City. The LDS leader received them warmly and with great curiosity, and asked one of the sisters where she was from. After she said she was Irish, Young replied, "[I] know what your people have suffered for their faith for centuries. I do not find such a spirit of unity, stability, and endurance as I find within the Catholic Church." Young likely respected Catholicism, particularly the Irish church, for its resoluteness in the face of English persecution, as it reminded him of the persecution the LDS Church had faced east of the Mississippi.

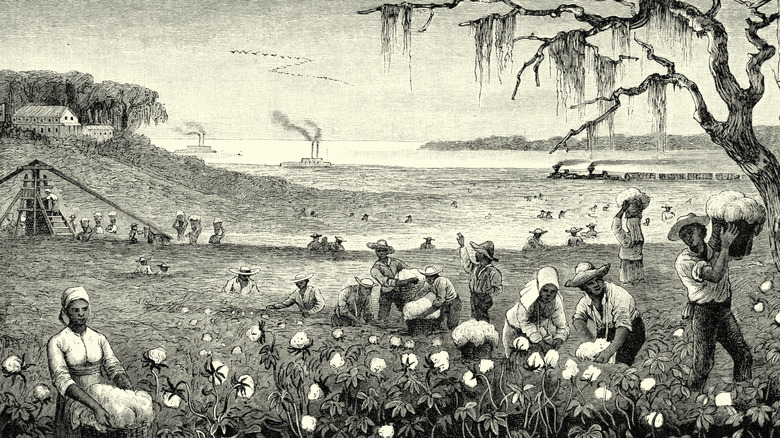

He supported enslavement, but not its supporters

Brigham Young was no crusader for racial equality – he banned anyone of African descent from the LDS priesthood in 1852 and supported enslavement as a divine institution. In his 1852 Discourse, he wrote that Africans would suffer enslavement until God lifted the curse he had placed upon them and ended the practice. Consistent with his beliefs, Young disliked abolitionists and the Republican Party, whom he accused of ripping the country apart with abolitionist rhetoric in his Discourse from 1863. But he hated pro-enslavement Southerners even more. After all, it was enslavers and supporters of the practice who had attempted to kill him and his followers in Missouri. The only thing separating the two sides, he said, was their respective attitudes toward enslaved Black people – otherwise, their conduct was indistinguishable.

Young also had a second, more humanitarian reason for opposing the pro-enslavement faction. He stressed in both discourses that enslavers must treat the people they enslaved like human beings, warning that God would curse the white race if they did not repent of their abuse. For the time, it was a relatively nuanced position, especially since many white people viewed Black people as subhuman.

When the Civil War broke out, Young, consistent with his anti-Southern position, kept Utah loyal to the United States. In 1861, he telegraphed President Abraham Lincoln that Utah would defend the American Constitution and its laws – presumably even if abolition, which he argued was legally within Congress' purview, came to Lincoln's desk.

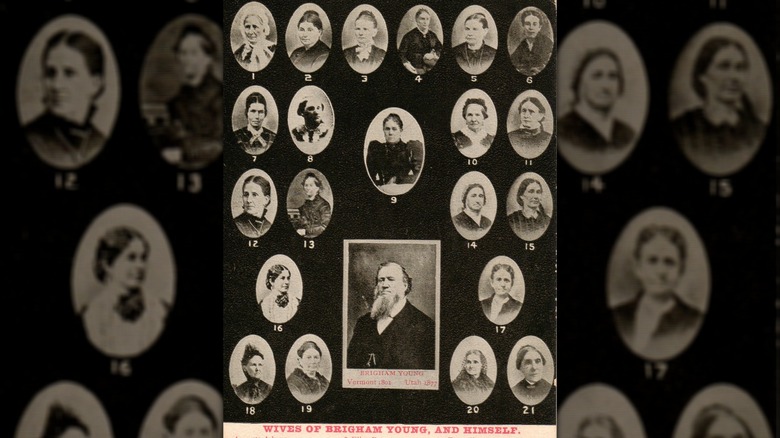

Not all his wives were wives

The Latter-day Saints permitted polygamy – a practice that drew ire from its adherents' non-LDS neighbors – and Brigham Young was no exception. Official LDS records list 55 wives, 49 of whom he had married by 1859. But that same year, he told New York Tribune journalist Horace Greeley (via the Salt Lake Tribune) that he only had 15 wives – a discrepancy that, on the surface, appears problematic.

LDS marriage practices are key to understanding Young's apparent contradiction. LDS marriage, properly called "sealing," has two forms. Today, the standard temple sealing is the equivalent of what many would consider marriage. It creates a husband-wife marriage bond, except the bond survives into the afterlife. Because the marital bond is eternal, widows who remarried could be proxy-sealed to another man on earth, who would provide for her material needs, while she would resume her role as her first husband's wife in the afterlife.

In his interview, Young appeared to allude to this when he told Greeley, "Some of those sealed to me were old ladies whom I regard[ed] rather as mothers than wives, but whom [I had] taken home to cherish and support." Thus, many of Young's wives were not wives in the traditional sense, but poor widows proxy-sealed to him for financial purposes.

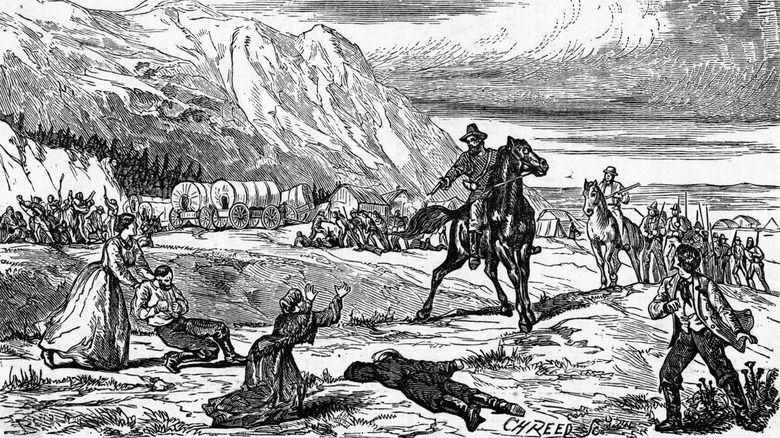

His adopted son was executed for treason

In 1857, the Utah War broke out after President James Buchanan replaced Brigham Young as Utah's territorial governor with a non-LDS appointee. In the ensuing conflict, a Utah militia and their Native American allies massacred a California-bound wagon train of Arkansas settlers – including women and children – at Mountain Meadows, despite promising them safety for turning back. The leader of the massacre was Young's adopted son, John D. Lee, who was tried for treason against the United States in 1876 and executed. The Latter-day Saints Church maintains the massacre was solely Lee's decision – Young just wanted to expel the settlers without killing them.

Lee's confession, however, alleged Young had sent one George Smith to plan the massacre. Once Lee's men had the settlers surrounded, his superiors, unbeknownst to him, asked Young for further instructions, who considered this "a sharp play on the part of the [church] authorities to protect themselves." Once the massacre was complete, Young would blame Lee, while arguing he would have stopped it had the messenger arrived in time.

If Lee was being honest (and if the testimony was not posthumously edited), he was sacrificed to protect Young. Lee regretted the massacre, claiming that he tried to save the women and children from the Native Americans, who were supposed to do the dirty work and keep Young and the LDS Church's hands clean. In his last words, he slammed Young, adding, "I have been sacrificed in a cowardly, dastardly manner."

He beat an alimony ruling by arguing polygamy was illegal

Ann Eliza Young was Brigham Young's 19th wife and the only one to divorce him. In her memoir "Wife No. 19: The Story of a Life in Bondage," she alleged that Brigham had abused her, failed to provide for her and her children, and even denied her medication and treatment when her health was failing. At the trial, Ann swore that she was living in penury, while Brigham was worth at least $8 million. Having no income of her own, she demanded alimony from the Latter-day Saint leader.

Brigham argued he owed Ann nothing because their marriage, although religiously valid in the church, was never legal since polygamy was illegal in the United States. This is where things got interesting. The judge warned Brigham that he was admitting to a felony, since he admitted to marrying Ann while he was still married to Mary Ann Angell. Thus, the judge ruled in Ann's favor and urged Brigham to pay the alimony and avoid future prosecution on bigamy charges. Under the terms, he would pay Ann $500 per month, alongside $3,000 in attorney's fees. Brigham refused and was jailed for contempt charges, along with a $25 fine.

The LDS leader, however, won on appeal. Judge David Lowe vacated the alimony order, ruling that both parties needed to admit the marriage's validity before considering alimony. Thus, Brigham walked away without paying Ann a cent.

He opposed temperance pledges as infringements on liberty

Temperance pledges, promises to abstain from drinking, were part of the Temperance Movement of 19th-century America. The Latter-day Saints generally forbade drinking alcohol, in accordance with the 1833 revelation to Joseph Smith called the Word of Wisdom, so one would have expected Brigham Young to support the movement's pledges. In an 1871 Discourse, Young supported Temperance's goal of reducing or eliminating drinking. In fact, he wrote that he wanted it to "go a little further and ... see them leave off, not only all intoxicating drinks, but those narcotic drinks — tea and coffee, and the men their tobacco."

Pledges, however, were not the answer. Young said that when he was young, his father wanted him to sign a temperance pledge. But in a very American response, he said, "Am I not a free man, have not I the power to choose [to do right or wrong], is not my volition as free as the air I breathe?"

Young's underlying logic was that free people should do good (in this case, live cleanly) for the sake of doing good – not by being bound to pledges that forfeited their free will. His position echoed Founding Father and President John Adams' argument that the "Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People." Young loved the Constitution, so it is unsurprising that he also embraced the idea that the liberty it provided went hand-in-hand with proper morality and self-restraint.

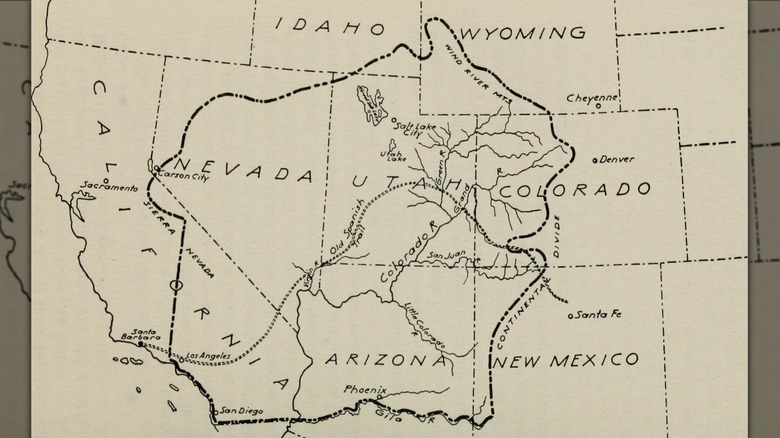

He envisioned a Latter-day Saint superstate called Deseret

Brigham Young and the LDS Church were accused of having secessionist sympathies contrary to American values. In reality, Young was no secessionist. Per BYU, he believed "the Constitution and laws of the United States combine[d] the best form of Government in force upon the earth." He just wanted Utah to join the U.S. as a state on its own terms.

In 1849, Young petitioned Congress to admit the soon-to-be Utah Territory – a massive entity stretching from Southern California to Colorado (pictured) – as the State of Deseret. The state's proponents even had the necessary institutions ready, including a legislature, constitution, and justice system. Congress, however, rebuffed him, instead appointing Young as governor of the Utah Territory. The provisional State of Deseret was then dissolved. Statehood proponents applied thrice more, while Congress worried about the potential influence and power of a large, strategically-positioned LDS superstate. Public opinion opposed the state over fears of an LDS theocracy that opposed the Constitution's principles and provided Congress the excuse to cut Utah down to size.

Congress gradually stripped Utah's territory. The precious metal-rich territories around Comstock were transferred to Nevada in 1861 due to secession fears. The northeastern part of the territory was transferred to Wyoming, the eastern portion to Colorado, and the remaining western part to Nevada. With that, the dream of the superstate of Deseret died.

He founded two rival universities

Brigham Young is perhaps best remembered for his namesake institution – Brigham Young University (BYU). But first, he helped found the University of Utah. As the Utah Territory grew, Young formed a board of regents to expand higher education and train teachers for the growing population of children. Thus, in 1850, the University of Deseret was born.

The university was initially a bit underwhelming. It had one professor, who taught all courses at a local woman's home. By 1851, it opened a small campus at the 13th Ward Schoolhouse with three professors, but an economic downturn forced it to close in 1852. When it reopened in 1868, demographic, political, and religious changes in Utah cut the Latter-day Saints Church out of any say in school affairs.

Young got his chance to create an explicitly LDS university when financial problems at the University of Deseret – Timpanogos in Provo nearly led to professors, who "had grown tired of seeking payment in 'turnips, molasses, and pumpkins,'" to quit. Young offered a generous trust to fund the new, explicitly LDS Brigham Young Academy in 1876, per BYU. This school eventually became Brigham Young University. Thanks to his role in creating both universities, Brigham Young can be considered the progenitor of Utah's greatest sports rivalry, between heavyweights the Utah Utes and the BYU Cougars – a national rivalry, too, as of 2024, thanks to BYU's entry into the Big 12.

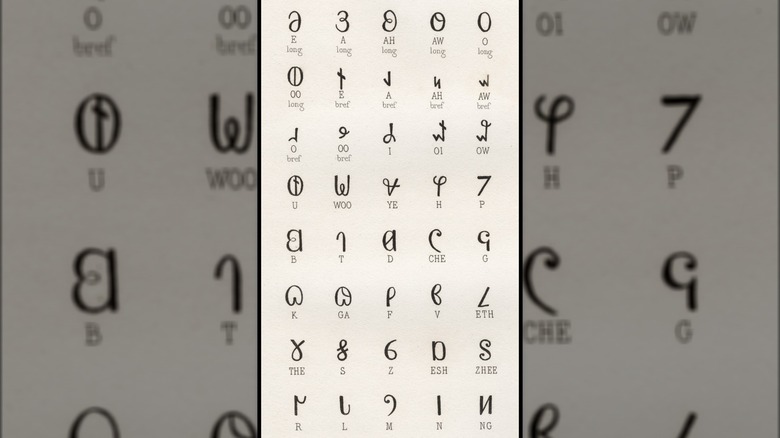

He wanted to reform English and make a new script

Among Brigham Young's more niche endeavors was the reformation of the English language. According to Orem Utah Institute of Religion instructor Richard Moore, Young had mixed feelings on English: "... in its written and printed form, [it was] one of the most prominent now in use for absurdity, yet as a vehicle in which to convey [Latter-day Saint] ideas verbally, it [was] one of the best."

Young hated English orthography, decrying the idea that one letter, like "a," could represent at least five different sounds. He also disliked redundant letters that made achieving literacy more difficult, and the variety of English vocabulary and dialects. They created confusion and ambiguity between different sets of speakers, defeating language's main purpose – communication. In response, Young and the Deseret Board of Regents created a new 38-letter, single-case alphabet on the principle of one letter, one sound.

The Deseret News praised the new alphabet, proposing it replace the Latin script because: "... if they [children] could find no better reading than much of the miserable trash that now obtains extensive circulation, it would be better ... if they never learned to read the present orthography." Children taught the new alphabet, however, would only have access to wholesome LDS literature, the paper argued, cutting out worldly evils that entered into youth's heads through books. In 1877, after over two decades, $20,000, and Young's death, the church shelved the new alphabet — mainly through lack of interest.

He did not place a blanket ban on intoxicants

The Latter-day Saint Word of Wisdom generally proscribes intoxicants. Given Brigham Young's reputation, one might think it was strictly enforced – but it was not. Young's 1861 Discourse on tobacco best summarizes his attitude towards intoxicants: An old lady in New York asked her doctor whether using snuff would cause brain damage. He responded, "It will not hurt the brain: there is no fear of snuff's hurting the brain of anyone, for no person that has brains will take snuff."

In the same discourse, Young noted that tobacco use was widespread among the LDS faithful, and urged young people to curb their passions. But he also admitted that, as humans, they had their weaknesses. Thus, Young refused to make adherence to the Word of Wisdom a litmus test for church membership. Instead, he exhorted his followers to quit their habits of their own volition because it was the right thing to do. In another Discourse, he proposed tobacco-chewers try lobelia for a similar taste, but without the addictiveness. They would prove to themselves that they did not need the substances because "Mankind would not become attached to these unnecessary articles were it not for the poison they contain."

Young admitted to using tobacco in a Discourse from 1867, but made it clear that it had been to treat a toothache. Thus, medicinal use of intoxicating substances was deemed acceptable, and remains the current LDS position.

He owned a distillery

Despite the Latter-day Saints' disdain for alcohol, 19th-century Utah was not a prohibitionist's paradise. In fact, according to the Utah Humanities Project, the territory was one of America's alcohol-producing powerhouses, noted by none other than Mark Twain. LDS and non-LDS alike used it as currency for bartering on the frontier. New converts did not easily give up their old drinking habits, while non-LDS immigrants working in Utah's mining sector wanted their booze. And the LDS Church was happy to oblige them.

Most of Utah's liquor producers – including Brigham Young himself – were LDS. Ever the capitalist, Young admitted in one of his 1863 Discourses that he opened and operated a distillery because, at the time, no one else was. He simply said, "When there was no whisky to be had here, and we needed it for rational purposes, I built a house to make it in." Even though, according to the LDS Church, "rational" in this case referred to medicinal uses, the church's alcohol ban was not yet absolute. Young preferred to focus on temperance rather than prohibition, and not just for religious reasons – there was a lot of money to be made.

Young chose to regulate legal alcohol production in Utah for tax purposes. Liquor licenses were a gold mine for Salt Lake City, which in 1871, charged a hefty $750 per month for a distillery license. He did, however, prefer that seedy establishments like saloons be kept out, or at least out of sight.