The Tragic History Of Mormonism

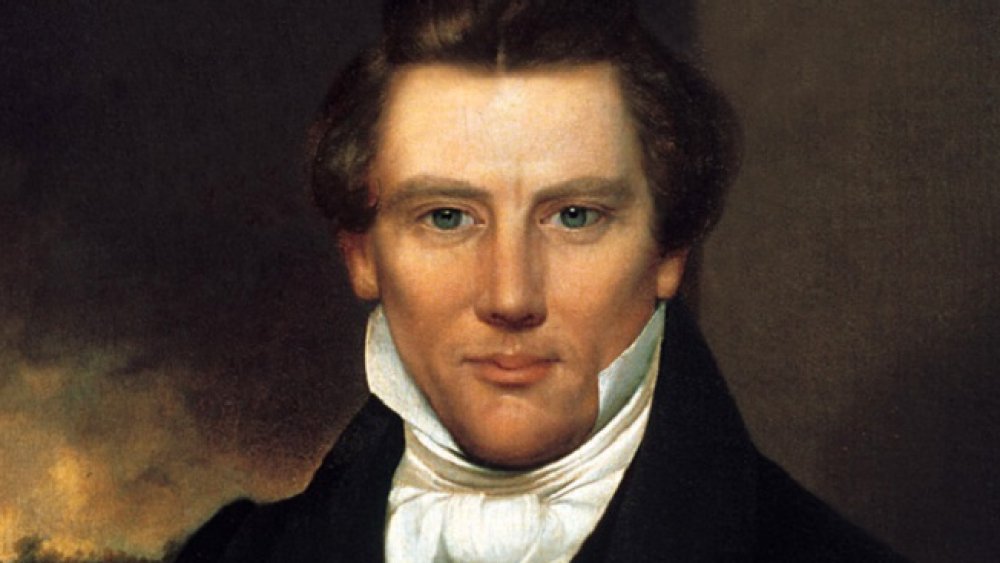

Joseph Smith was born in New York state in 1805, a time and place that was just lousy with religious fervor. Smith embraced this spiritual frenzy, and by 14, he was having visions of God, Jesus, and angels. God supposedly told him no church had nailed the whole religion thing yet, and that he needed to start a new one. So Smith found some golden plates, translated them into the Book of Mormon, and started converting people.

All religions have to begin somewhere, and usually, they face persecution at first. But the early Latter-day Saints, more colloquially known as Mormons, saw a crazy amount of suffering and violence in a very short time. Sometimes, this wasn't their fault, as it was brought on by outsiders. Other times, it was policies within the church that hurt its own members. And then there were the atrocities Mormons committed on others. Whatever the reason, the LDS church would go through a hell of a lot before becoming mainstream enough for Mitt Romney to run for president. This is the tragic history of Mormonism.

Mormon women weren't thrilled about polygamy

The early Latter-day Saints are most famous for practicing polygamy, a form of marriage that was just as weird and controversial then as it is now. (Yeah, we're looking at you, Warren Jeffs.) According to PBS, Joseph Smith started thinking about plural marriage as early as 1831, but he lied about it. Publicly, he told everyone who would listen how bad a man marrying more than one woman was. Meanwhile, he was taking part in so many weddings it's amazing he found time to do anything else. Big Think says it's estimated Joseph took anywhere between 29-48 wives during his lifetime.

Joseph Smith wasn't just worried about the reaction of other people. He first had to deal with the anger of his wife, Emma. True West magazine describes Emma (pictured), who married Joseph in 1827, as "the first woman to 'despise' polygamy." She read his revelation, allegedly from God, that he needed to marry more women in 1843, and she wasn't having it. He went ahead with his plans anyway, which was "an excruciating ordeal" for her.

Nor was it necessarily great for those other women. Joseph would basically tell a woman that God had ordered him to take her as another wife, and she didn't have much choice in the matter. A woman named Eliza found the idea of marrying the prophet "repugnant," and other women probably felt similarly, especially when he also married their sisters or mothers. Sometimes those women were already married to other men. And they weren't all grown women, either. At least one of Joseph's wives was a girl of just 14.

The Mormons faced an extermination order in Missouri

Because the Mormons were a new, slightly weird religious group, people didn't trust them. This led to serious problems in their early history. According to PBS, after the Book of Mormon was published in 1830, Smith was arrested for "being a disorderly person." Even though he was acquitted, life in New York probably didn't seem that great anymore. Missionaries of the LDS church had already made inroads in Ohio and Missouri, so Smith made tracks.

But trouble followed him. Locals were never happy when the Mormons showed up. In 1832, a mob in Kirtland, Ohio, tarred and feathered Smith in front of his own house. A year later, non-Mormon residents of Missouri destroyed an LDS printing press and drove some Mormons out using mob violence. The Saints responded by forming paramilitary groups. When a Missouri election in 1838 resulted in a riot after locals tried to keep Mormons from voting, it led to even more violent encounters between the two groups.

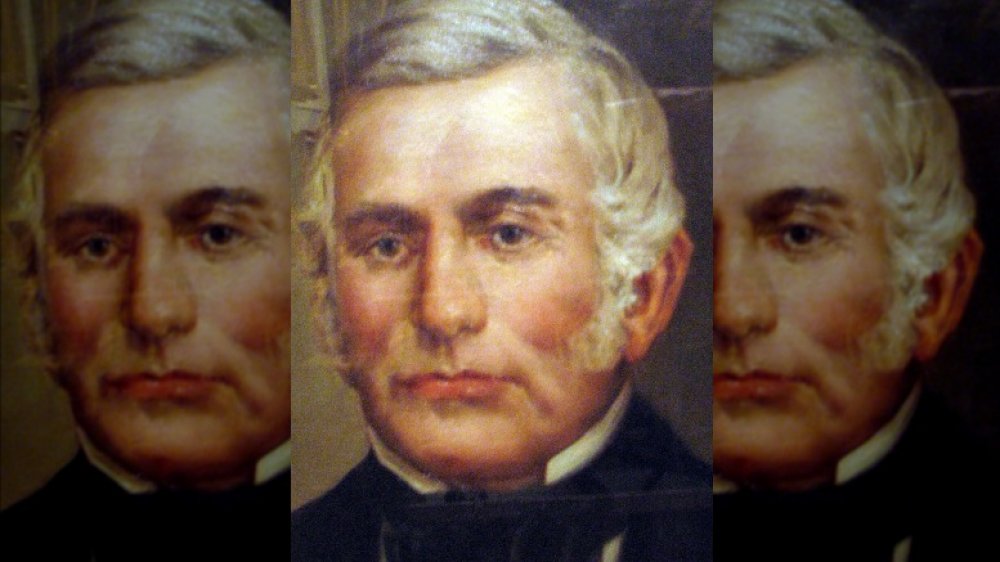

Governor Lilburn W. Boggs (pictured) heard rumors about all the issues with the Mormons, and he went nuclear, issuing Missouri Executive Order 44. The order stated, "The Mormons must be treated as enemies and must be exterminated or driven from the state, if necessary for the public good. Their outrages are beyond all description." The Chicago Tribune reports that what became known as the "extermination order" was technically in place until 1976, when it was finally rescinded by the then-governor of Missouri.

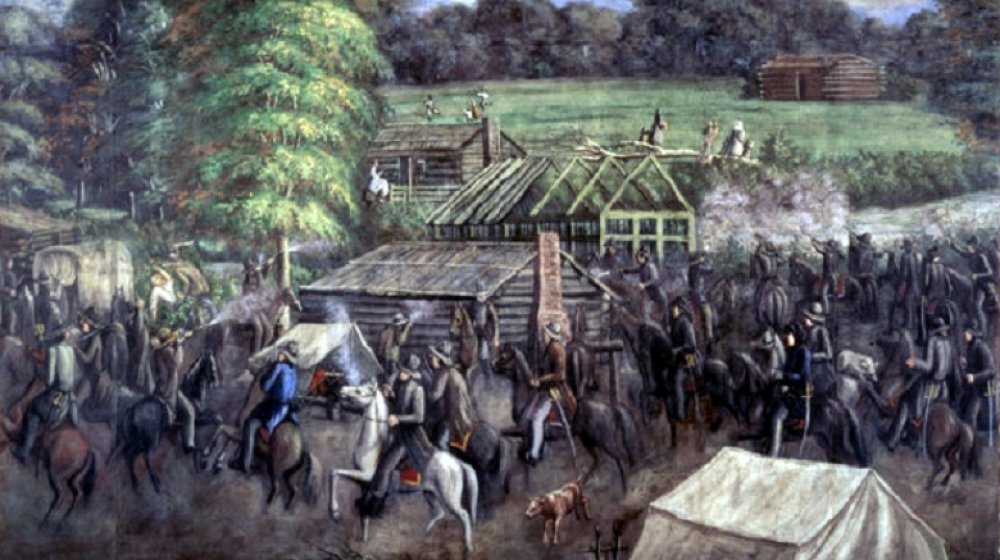

The Haun's Mill Massacre was a tragedy

The 1838 extermination order issued by Governor Lilburn Boggs was exactly the permission that hostile locals needed to go after the Latter-day Saints in a big way. And that year saw the start of what would become known as the Missouri Mormon War. Three days after the order was signed, on October 30, a slaughter occurred which BYU Professor Alexander L. Baugh called the "singular most tragic event in terms of loss of life and injury enacted by an anti-Mormon element against the Latter-day Saints in our entire church's history."

According to PBS, that afternoon, a group of 240 non-Mormon men rode into the small Mormon village of Haun's Mill (sometimes spelled Hawn's Mill). Despite a "flag of truce," and with no warning, they started shooting. Residents fled to the blacksmith's shop, but the mob just stuck their guns through the cracks in the logs and kept firing until "most in the building [were] dead." Around 1,600 rounds of ammo were spent on 40 people. A shocking 18 or 19 were killed, and around 15 were wounded, including a woman, a seven-year-old boy, and men in their 70s. After it was over, survivors dumped the dead in the town's well and fled.

It was, pretty much by definition, overkill. The Mormons were seriously outnumbered, had no advanced warning an attack was coming, and weren't even involved in any kind of direct conflict with the men who killed them. It was the darkest moment in the Missouri War, and within the next year, 8,000 Mormons fled the state.

Joseph Smith becomes a martyr

By 1844, Joseph Smith was the head of a growing religion, and he was presiding over the all-Mormon town of Nauvoo, Illinois, where he was mayor, lieutenant general of the Nauvoo Legion, and in charge of the local liquor monopoly, according to The Washington Post. He was feeling so sure about himself that he ran for president of the United States. But then a newspaper run by former Mormons published allegations of Smith's polygamy. Smith ordered the paper's printing press destroyed. In response, he was charged with treason and conspiracy, and a warrant was put out for the prophet's arrest. Smith thought about fleeing, but he'd gotten out of worse legal scrapes before, so he turned himself in to law enforcement and was held in jail.

But local men had no intention of letting Smith get off with a trial. Nor did they drive him out of the state, as opponents of Mormons usually did. Instead, on June 27, 1844, a mob of "respectable" men, including "a prominent newspaper editor, a state senator, a justice of the peace, two regimental military commanders, and men who just a few months before were faithful members of Joseph's church" stormed the jail and murdered both Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum. One historian, who isn't Mormon himself, calls this martyrdom "without parallel" in American history.

There was no retaliation from the Latter-day Saints. Instead, led by Brigham Young, they fled again, this time all the way to what is now Utah, founding Salt Lake City.

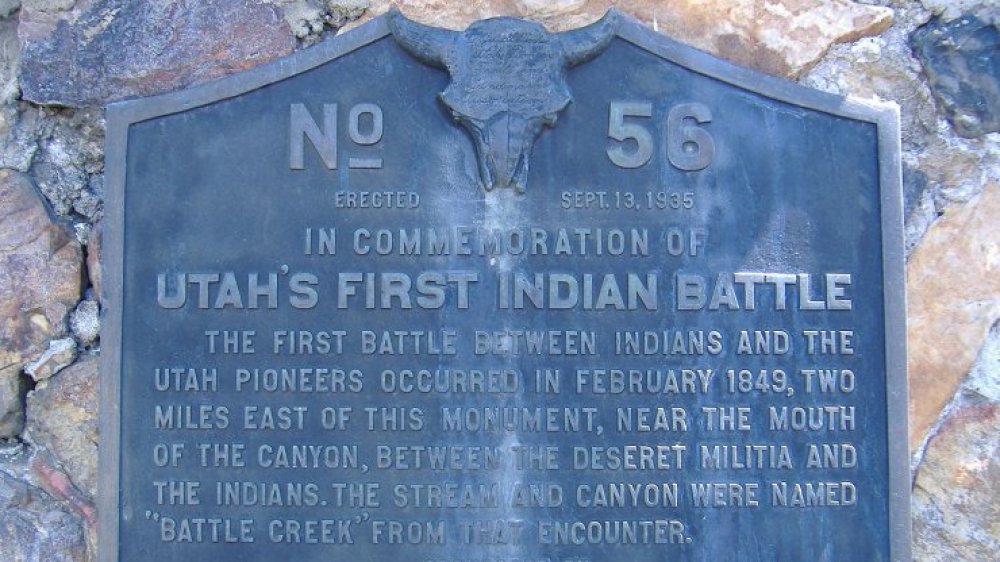

The Mormons vs. Native Americans

The trek to now-Utah, which wasn't part of the US at that time and essentially at the ends of the earth, was difficult for the Mormons. But once they got there, things got worse. Just like everywhere white people showed up and claimed land, it turned out not-so-white people were already living there and were kind of using that land, thank you very much.

In 1849, Brigham Young blamed a "renegade band of Indians" for stealing some of his horses and cattle, so he sent a militia of 44 Mormons to get them back, according to The Black Hawk War: Utah's Forgotten History. Captain John Scott attacked a group of Native Americans at Battle Creek, killing at least four men and taking 12 women and children captive. This event became known as the Battle Creek Massacre and the "first battle with the Indians." It wouldn't be the last.

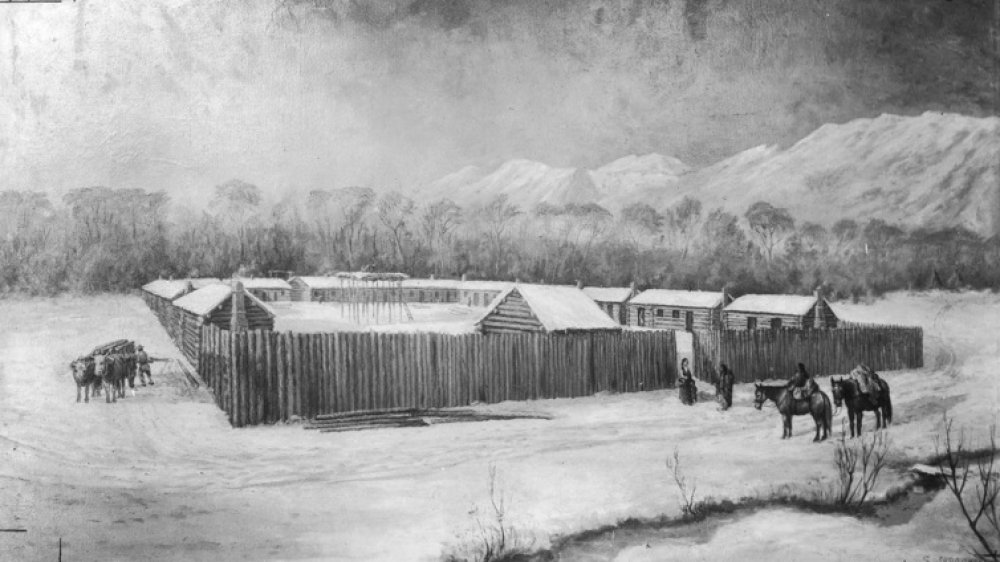

Just a few days later, a group of about 150 Mormons left Salt Lake City for what would become Provo, with orders to settle there and "remove the Indian people from their land." The Saints built Fort Utah and started competing for resources and food with the Native Americans, causing tensions. The local tribe, the Timpanogos, ended up starving and dying of measles, with the Mormons refusing to help. Then three Mormon men murdered an Indian named Old Bishop in cold blood and boasted about it. Problems between the two groups were coming to a head.

The horrific Battle at Fort Utah

The Native Americans were obviously furious over the way they were being treated by the Mormons, especially when one of their own was murdered in cold blood. Their entreaties for some kind of justice were ignored. Instead, the Mormons decided to go to war. According to The Black Hawk War: Utah's Forgotten History, Brigham Young supplied Fort Utah with arms and ammunition, saying he thought the settlers should kill the Native Americans, that there would be "no peace until the men [are] killed off," but that they could "let the women and children live if they behave themselves." Lieutenant General Daniel H. Wells gave the official order to "exterminate the Timpanogos."

On February 29, 1850, a group of 50 Mormon troops surrounded a camp of sleeping, unsuspecting Timpanogos and opened fire. For two days they battled, and then the Mormons tracked those Native Americans who'd managed to flee. Utah Humanities says once they found them, the men were slaughtered. Others may have died from exposure. An estimated 102 Timpanogos were killed, as well as 11 Utes, compared to one Mormon militiaman.

But the Mormons weren't done with their atrocities. They looted the corpses of valuables. Then the bodies of the Native Americans were mutilated, with militiamen cutting off the heads of up to 50 bodies and taking the skulls as trophies. They brought them back to Fort Utah, where one, belonging to a man named Big Elk, was proudly hung "by its long hair from the willows of the roof of one of the houses."

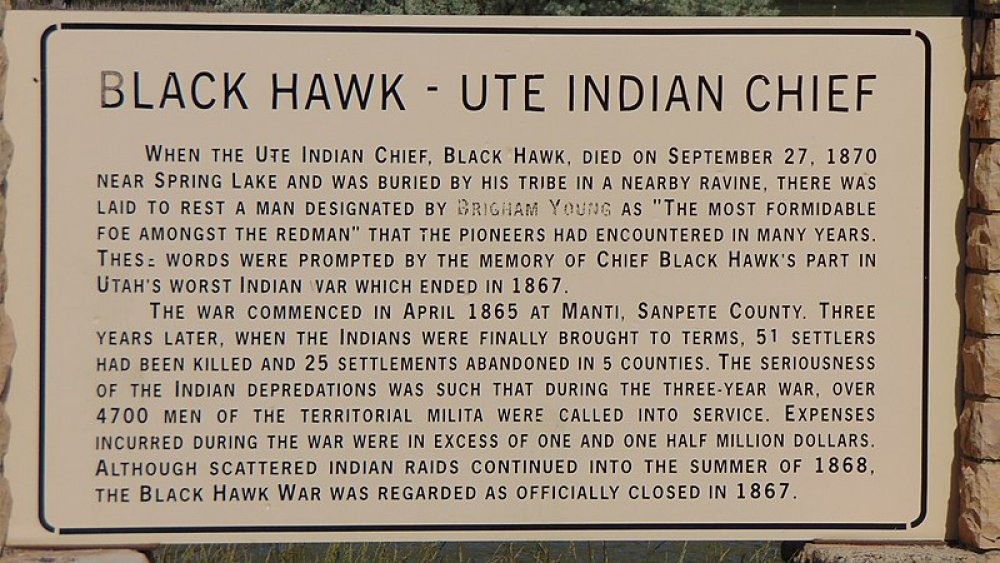

The Mormons fight the Black Hawk War

After slaughtering the Timpanogos and Utes in 1850, things didn't exactly get better between the Native peoples and the Mormon settlers. The Indians continued starving while the interlopers hoarded food and resources. There were skirmishes between the two sides, until finally on April 9, 1865, representatives of the Utes and the Mormons met to try and resolve their differences. However, according to Utah History Encyclopedia, an angry (and probably drunk) Latter-day Saint yanked a young chief off his horse. The Natives stormed off, vowing retaliation for the insult. And they meant it.

Over the next few days, Utes killed five Mormons and stole thousands of heads of cattle, led by a man known to the whites as Black Hawk. By the end of the year, thousands of more cows had been stolen, and 25 more settlers were dead. Eventually, that number would rise to 70 Mormon casualties.

The Latter-day Saints "considered themselves in a state of open warfare" with Black Hawk's followers and started killing Native Americans indiscriminately, even if they were from friendly tribes. The United States government, still suspicious of the Mormons, ignored their pleas for help, but it didn't tell them to stop killing Natives either, and hundreds died. The war raged for two years, until things started chilling out a bit in 1867, and a year later, Black Hawk signed a peace treaty, although hostilities between the two groups continued on and off until federal troops finally showed up in 1872. Even now, the Black Hawk War remains the "longest, costliest, and bloodiest" conflict in Utah's history.

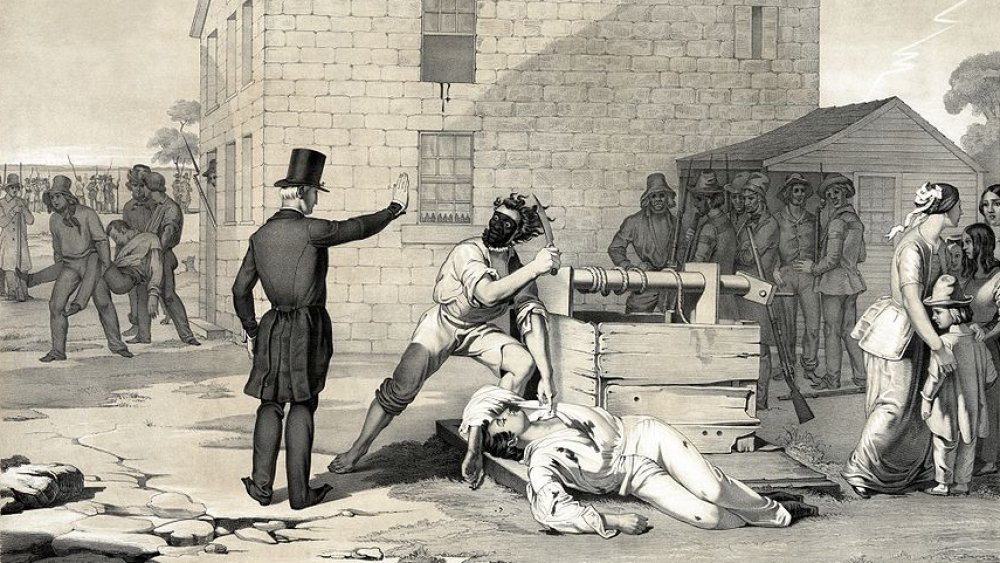

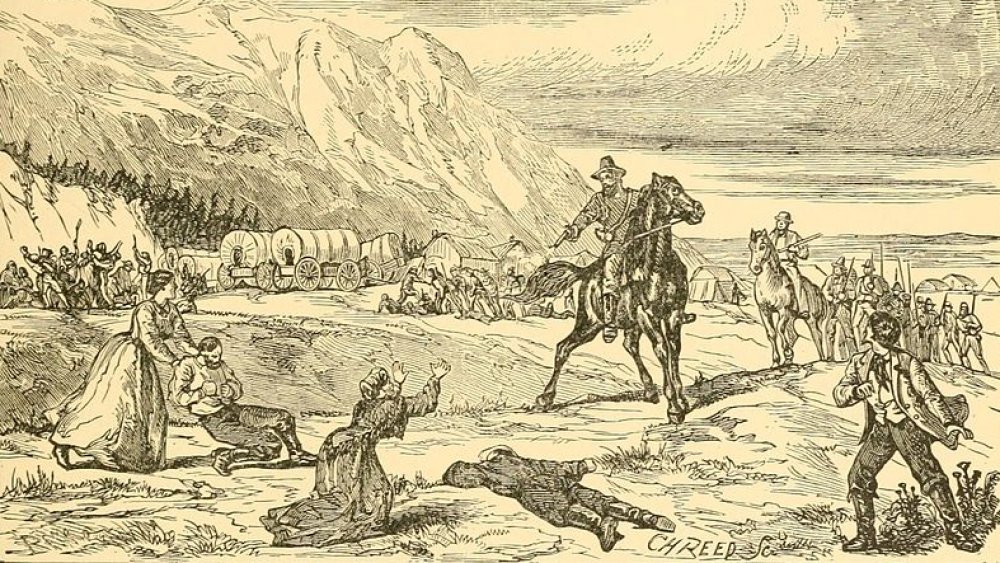

The other September 11: the Mountain Meadows Massacre

It wasn't only Native Americans who the Mormons killed in cold blood. On September 11, 1857, they did something so atrocious that descendants of those involved are still dealing with the repercussions today, according to NPR. What would become known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre was "horrific" and "the worst event in Latter-day Saint history."

Plenty of non-Mormon pioneers were moving out West. This was a time of rapid expansion, and wagon trains of new settlers were common. HistoryNet records the Baker-Fancher wagon train was made up of people headed from Arkansas to California. They had no issues with the Mormons and were just passing though.

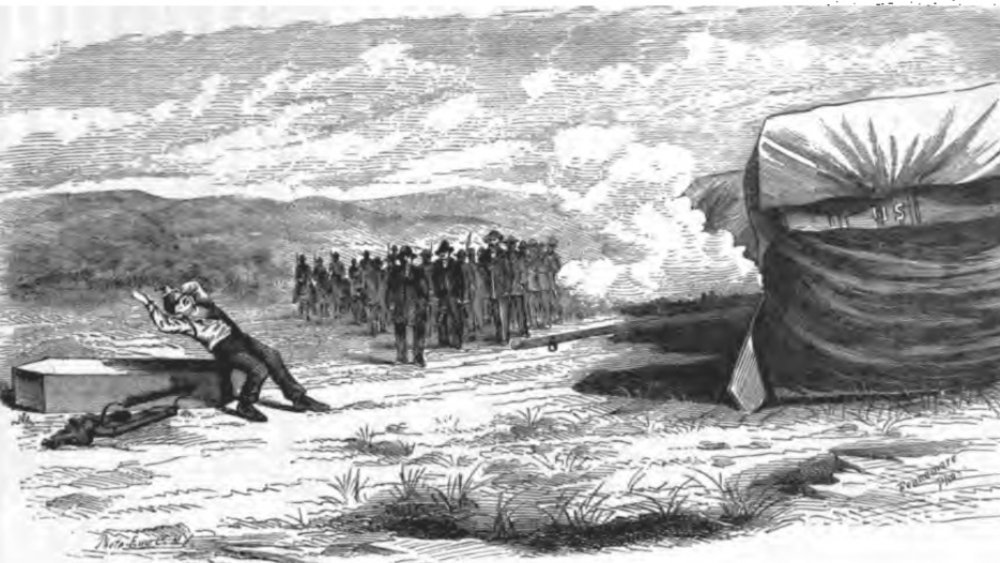

For reasons that remain unclear, on September 7 or 8, a militia made up of Mormons and some Paiute Indians attacked the wagon train. This resulted in a siege, with the travelers running out of food and water within days. On September 11, the Mormons raised a white flag, walked into the camp, convinced the men to put down their arms, and escorted everyone away. They marched for a while, then a sign was given, and the Mormons turned and shot the men pointblank. Women and children were "chased, clubbed, knifed, and shot." As many as 140 people were murdered, with only 17 very young children spared.

The Mormons tried to cover up what they did, blaming the Indians and destroying evidence. Only one man was ever convicted for his role in the massacre.

The crazy doctrine of Blood Atonement

If it seems like the Mormons were trigger-happy, that might be because of a controversial doctrine of the early church. According to Joseph Smith himself, (via Famous Trials) some sins were worse than others. Some sins were so super duper bad, there was only one way to get forgiveness for them: The sinner had to bleed. Sure, regular Christian doctrine says that Jesus' blood was spilled to atone for everyone's sins, no matter how serious, but Smith said nuh-uh. For sinners that were "beyond the reach of the atoning blood of Christ" the "only hope" was bleeding all over the darn place, up to and including dying.

Brigham Young took Smith's idea and ran with it. But maybe a sinner disagreed they were that bad. Maybe they wanted their blood to stay on the inside. In that case, Brigham Young asked his followers, "Will you love that man or woman well enough to shed his blood?" In other words, if Mormons killed evil people, whether they were part of the church or not, it was actually a good thing. They were saving souls.

This was such a controversial idea, let alone practice, that the Saints abandoned it in 1889. Since then, church leaders and Mormon historians have tried very hard to deny Blood Atonement was ever a doctrine or anything more than a theoretical idea. Sermons encouraging it were supposedly simply part of the "rhetorical, emotional oratory" style of the time. So take your pick.

Mormon racism runs deep

While plenty of groups in America have a bad history on race relations, the Later-day Saints are especially notable. The foundation of the church's racism is right there in the Book of Mormon, which says the new religion "shall be a white and a delightsome people." Eek.

But it gets worse. According to The Atlantic, one of the big set pieces of the Book of Mormon is the conflict between the "light-skinned population called the Nephites and the dark-skinned population called the Lamanites." Guess who the bad guys are? The Lamanites had actually been white at one point, but then they did terrible stuff, and God got mad at them, so the book says He "cursed" them by turning their skin black.

This kind of bias wasn't limited to Mormon scripture. It affected things in the real world for almost 150 years. One early convert named Jane Manning James (pictured) made the long, dangerous trek to Salt Lake City, and she was close with Joseph Smith's family. But she was also black. Smith's brother assured her this wasn't an issue, since she could "actually overcome [her] lineage and join a pure lineage." Pure lineage being white people, of course. But since she couldn't become white in a literal sense, she was "denied access to important religious rites during her lifetime because of her skin color." Blacks were kept from the priesthood and certain temple rites until the 1970s, and the church "didn't repudiate its past teachings on race until 2013."

The Mormon Trail was a horror show

Traveling from Illinois to now-Utah after Joseph Smith's death was incredibly difficult. It was a 1,300-mile trek, before cars, roads, modern medicine, air conditioning, or heaters. But the Church asked believers to do it, saying, "Let them come on foot, with handcarts or wheelbarrows; let them gird up their loins and walk." While girding one's loins sounds fun and all, walking 1,300 miles while pulling a handcart with all your belongings and children in it does not. A "short" journey to Utah might only take nine weeks, but others would struggle across the trail for up to four months.

But for many, the journey had started long before. These days Mormons are famous for their missionaries, and that's kind of been their thing from the beginning. According to Legends of America, thousands of Mormon converts moved all the way from the UK and Scandinavia, told to come help protect the original group of Mormons now in Utah by increasing its numbers.

The number of convert immigrants would be significantly reduced by the time they got there, though. In 1856, two groups of handcart Mormons started late and hit trouble. The going was so slow they began running out of supplies, and they discarded extra weight, including important items like blankets. When blizzards hit, people started dying. Others had body parts amputated to stop frostbite and gangrene. In the end, over 200 people, more than 20 percent of those who set out in the groups, died before reaching Salt Lake City.