The Most Disturbing Part Of Pompeii's Destruction Isn't What You Think

You might think the most disturbing part of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii, Herculaneum, and other towns was that the people living there had no warning. If they had better technology, or even saw a bit of smoke or a stream of lava, they might have realized what was going on and been able to escape in time. It's the inevitability of the deaths of thousands of people that seems so tragic; like it's ridiculously unfair they weren't given a fighting chance.

But that is nowhere near the worst part about Pompeii's destruction in A.D. 79. While written records of the event are virtually nonexistent, we've learned a lot about it through archaeology, and almost all of it is tragic. Whether it's the terrified faces of the dead staring back at us, exploding heads, or modern-day grave robbing, there are plenty of disturbing things that happened at Pompeii.

The residents had warnings, they just didn't heed them

Two concurrent festivals meant the tragedy at Pompeii was so much worse than it should have been. According to the book Pompeii: An Archaeological Guide, residents were in the middle of a multi-day celebration for Augustus. The emperor had died 65 years earlier and was made a god, as well as having the month of August named after him. This meant there were public celebrations including street musicians, fortune tellers, plays, and athletic events. Obviously, performers and athletes who wouldn't normally be in the town were there, as well as plenty of visitors who came to see them. We can't know how many extra people were there, but it is certain a lot more lives were suddenly in the path of the volcano than would have been in a different month.

It gets even worse, though. The day before the eruption, August 23, was Vulcanalia, the festival of the god Vulcan. He was the god of fire and volcanoes, which is where he was supposed to keep his forge. It wasn't that the people in Pompeii didn't get a warning Mount Vesuvius was going to erupt because there definitely would have been smoke, small earthquakes, and loud rumblings at the very least. It was that because of Vulcanalia, they would have interpreted these signs as good omens from the god rather than warnings to get out. Any disruptions would have just been a sign Vulcan was busy at his forge in Mount Vesuvius, happy everyone was celebrating his special day.

Weird weather sealed everyone's fate

It wasn't just the timing of the festivals that screwed everyone over — it was also the weather. Perspecta Weather says normally in that part of Italy in August, the wind blows in a southwesterly direction. If this had been the case during the eruption, the cloud of ash and gas from the volcano would have blown away from Pompeii. Sure, there was still the issue of heat and lava, but that wasn't what killed most people in the city. If the ash and gas had gone in the usual direction, a lot more people probably would have survived.

But for some weird reason, that day the wind was blowing to the northwest, straight toward Pompeii. This meant clouds of ash and gas that smothered people, but it also meant that many of them couldn't escape. Pompeii is on a bay, and some people would have tried to escape by ship. But our only eyewitness account of the tragedy, by Pliny the Younger, says the wind was blowing "dead in-shore" and stopped terrified residents, including his uncle, from leaving that way. Their most effective escape route was blocked off because of the bizarre weather.

And it was totally bizarre. So strange, in fact, that some historians think we have the date of the eruption wrong. According to the Australian National Maritime Museum, the unexpected wind pattern, along with some fruit and the weight of the clothing some people were wearing, could mean the eruption was actually later in the autumn.

We can see how scared everyone was as they died

It's easy not to feel too sad over the deaths of people who lived 2,000 years ago. After all, it's not like they would be alive now. But with Pompeii, we don't just have skeletal remains of those who died, we can actually see in great detail the unbelievable fear on their faces at the moment of death. These images take it from a historical event to something incredibly disturbing.

When Pompeii was being excavated in the early 1800s, the archaeologists realized that when they found a skeleton, it was always surrounded by a void in the compacted ash. Atlas Obscura says the diggers started pouring plaster of Paris into the spaces. What emerged were emotionally moving casts of people in their last moments of life. They could see the positions they took as the ash rained down. Many huddled together in groups, with some couples embracing. There are even animal casts, including one of a dog writhing on its back, twisted as if in great pain.

But modern technology can take this information even further. Seeker reports that in 2015, many casts were CAT-scanned. This means we now know the victims' ages, sexes, and details about how healthy they were. We can see even more detailed images of their faces, like a 4-year-old boy frozen in terror or a baby asleep on its mother's lap. The head radiologist said, "Working with these casts was extremely moving; it felt like I was dealing with real patients."

We have a horrible account of the people screaming for their lives

Pliny the Younger is our only eyewitness to what happened, and he didn't write about it until more than two decades later. But his account shows that watching the city's destruction had a profound effect on him.

According to Eyewitness to History, Pliny was 18 and living across the bay in Misenum when the eruption started. Pliny's uncle, who was an important guy, decided to go to Pompeii and try to rescue people. Pliny and his mother were left to escape their city on their own. They left their house because the earthquakes made staying inside dangerous, and they had to keep shaking off ash so they wouldn't be crushed by the weight of it. People were panicking, and some spread false rumors about Misenum being on fire.

But the noise was the worst: "You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men; some were calling their parents, others their children or their wives, trying to recognize them by their voices. People bewailed their own fate or that of their relatives, and there were some who prayed for death in their terror of dying. Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore."

Obviously, Pliny might not remember exactly after 25 years, but hearing something like that probably sticks with you. His uncle died at Pompeii, unable to save anyone, even himself.

People in neighboring towns died straight out of a horror movie

Historians are surprisingly still not 100 percent sure how people in Pompeii died. It's mostly accepted that, in general, they were smothered by ash and gas, crushed when buildings collapsed, or hit and killed by falling debris. This is why the bodies archaeologists have found (or the cavities they left behind) show people were intact when they died. But this might not have been the case for victims in other cities affected by the eruptions.

According to National Geographic, in the cities of Herculaneum and Oplontis, things were more disturbing because they were probably hit by pyroclastic surges. These are mixtures of ash, lava blobs, and noxious gases. But their key features are heat and speed. They can move 50 miles an hour and reach temperatures of 1,300 degrees Fahrenheit.

That kind of heat, not there one second then all-consuming the next, can effectively "immediately flash-fry a person to death." In more scientific terms, it causes a person's bodily fluids to boil instantaneously, including those inside their brain. That means their head explodes. Within 10 minutes, all the soft tissue on their body would vaporize. There's a lot of evidence that this happened to many victims in Herculaneum and Oplontis.

This was the accepted hypothesis for how people in those places died for a long time. And a major study in 2018 seemed to settle the matter. While there are at least a couple academics who still think such horrors were unlikely, the scientific evidence is pretty overwhelming.

Many people have tried to censor Pompeii's art

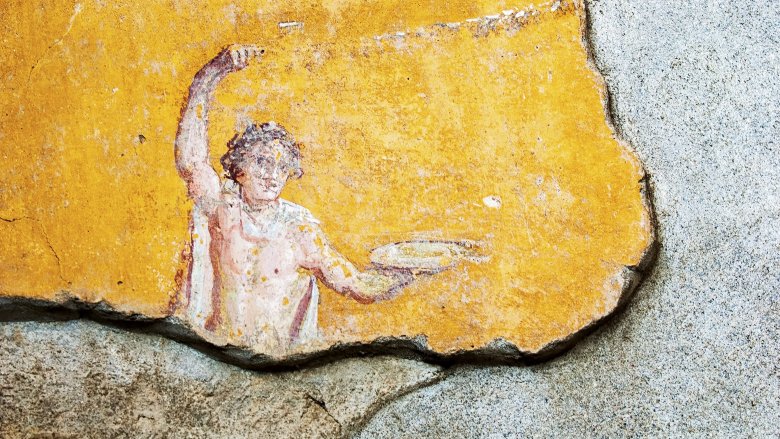

One of the only good things about Pompeii's destruction and the way it happened was that the art was preserved in unbelievable condition. Two millennia under airtight compressed ash meant there was nothing to destroy it. So it's a great way to learn about what life was like in the city at that time. What we've mostly learned was that the citizens of Pompeii had extremely dirty minds.

The Telegraph reports that it wasn't unusual for Pompeian households to have schlong-shaped oil lamps and statues of the fertility god Priapus, whose giant boner was supposed to be a threat to potential thieves. Walls of brothels and even normal houses would have mosaics of couples mid-coitus. And when the British Museum put on Pompeii exhibition, they included a parental guidance warning because of a statue of Pan graphically getting it on with a goat.

But this was far from the first time someone thought it best to censor the city's treasures. In fact, their filthy artwork might be what saved Pompeii on an architectural level. According to Casa Scola, Pompeii was lost to history until workmen digging an underground channel in 1599 unearthed some of it. They called in an architect who was so shocked by what he found that he covered it all back up again. Then when excavations started in earnest in the 1800s, the most salacious stuff was moved to the "Secret Museum" in Naples, and only men of "mature age and respected morals" were allowed to see it.

The eruption saved art, but it was a tragic lie

One of the problems with all the lovely adult art is that what it showed was totally inaccurate, especially in brothels (or places that had a side business as brothels, like inns, lunch counters, and taverns). The eruption of Mount Vesuvius saved a false narrative of history that made these women look a lot happier than they were.

According to the Conversation, the images of couples in the act on brothel walls were supposed to get customers in the mood, while also serving as a kind of menu for the options available. The positions shown might also have acted as instructions for some of the less experienced customers. The pictures show fair-skinned women, naked except for the occasional jewelry, with perfectly styled hair, coupling with young, tanned, athletic men. They are doing it on ornate beds with fancy quilts.

In reality, prostitutes met with clients in unbelievably tiny cells. Very few had windows, so they were dark and damp. Many didn't have doors, just a curtain for minimal privacy. The beds, and indeed the rest of the cells, were made of stone. Since free women could only sleep with their husbands, the prostitutes were all slaves.

Because most marriages were arranged and men were not supposed to expect anything but the most vanilla experience in bed with their wives, and only in order to conceive, it was considered vital to society that they seek pleasure elsewhere. But the women (and sometimes men) that they got it from lived horribly.

Grave robbing is rife, and sticky-fingered tourists don't help

If Egypt has taught us anything, it's that people really do not give a toss about the sanctity of the dead, with tombs being ransacked as soon as they were sealed. The same is true in Pompeii. Despite it being the final resting place for thousands of victims, all grave robbers think about is how much shiny stuff is buried with them. And the residents who fled their homes in terror did make it easy for these thieves, since many of them grabbed all their valuables to bring with them.

Since Pompeii wasn't even really rediscovered until the 1700s, these grave robbers are modern and active up to the present day. Pompeii's official website mentions archaeologists unearthing one room and finding tunnels dug in the ash and the skeletal remains of six individuals thrown around; damage done by humans, not a volcano. A shop was discovered in 2016 with evidence that looters had been there first, but they managed to miss a lot of gold coins, thankfully. In 2017, there was so much tomb raiding that for the archaeologists it became a race to dig out new areas before they were found by crooks.

Some people who steal aren't digging tunnels, though. They just pick stuff up when they visit as tourists. And a lot of them come to regret that decision. According to the Telegraph, in recent years, authorities have been sent a hundred packages returning things pilfered as souvenirs. Apparently, many people think they bring bad luck.

A massive disaster could totally happen again

To this day, the volcano that destroyed Pompeii is considered the most dangerous in the world. Mount Vesuvius made it pretty clear it wasn't messing around when it buried numerous towns and killed thousands of people. The eruption in A.D. 79 wasn't even the most destructive in terms of damage — that happened in 1631. But for some reason the area at its base is still prime real estate.

Six million people currently live close to Vesuvius (including in the city of Naples, which is about 12 miles away), and according to Volcano Discovery, 3 million of them are at serious risk if it ever blows its top again. The problem is that Vesuvius tends to get very angry, very quickly. Unlike some volcanoes, there aren't lots of small warning eruptions before a giant one. Vesuvius has a pattern of sitting perfectly quietly for a while and then suddenly letting off a massive explosion. It also has a much faster timescale for eruptions than other volcanoes, so even though it last blew in 1944 it couldn't go again any time now. Even some supervolcanoes aren't considered as dangerous as Vesuvius.

The Italian government has multiple plans for what to do when there is another eruption. At a minimum, 600,000 people would need to be evacuated from the immediate risk zone on the lower slopes of the volcano. Unfortunately for everyone in the vicinity who doesn't want to be smothered by ash, "it is quite doubtful whether such plans are realistic or could be effective."

The cultural wonder was neglected for decades

Perhaps the worst thing to happen to Pompeii since the eruption was the fact it wasn't properly taken care of. And it wasn't the archaeologists in the 1800s who screwed up, but those in charge in the second half of the 20th century.

In 2008, the Guardian reported that the Italian government declared a state of emergency at Pompeii. Not because the volcano was about to erupt again but because the historic site was in such a state of disrepair. The conditions were described as "squalid," with the amazing wonder swarmed by souvenir hawkers, fake parking attendants, bogus tour guides. It had few signs, not enough security guards, and only three bathrooms. The third of the site that was still buried was being used as an illegal trash dump.

But more dire, according to Reuters, was the "decades of neglect" the UNESCO World Heritage site had suffered. Visitors "expressed shock at the site's decay." Frescoes and stones that had survived almost 2,000 years were deteriorating at an alarming rate, with thousands of pieces lost every year. Restoration work that had started in 1978 was still nowhere near being completed.

"To call the situation intolerable doesn't go far enough," the culture minister said, and he declared a year-long state of emergency. A special commissioner was appointed to try to save the site before human laziness destroyed the place 2,000 people died two millennia ago.

The eruption preserved tons of poop for researchers to study

On the plus side, while it killed an estimated 2,000 people, Mount Vesuvius did the future a solid with all the things it preserved. The artwork is priceless, the bones and teeth of the dead tell us about their life and health, and it even saved archaeologists a giant pile of poop.

While this would seem pretty disturbing, researchers are so excited about this poop. According to National Geographic, by 2011, 10 tons of excrement had been excavated from a cesspit beneath Herculaneum. This is an "unprecedented deposit," and historians can learn all kinds of things by sifting through it. Digging through 2,000-year-old poop probably wasn't what they thought their career would hold when they decided to major in history, but there you go. The research involved sifting the ancient Roman stool through different grades of sieves to remove large and small objects.

Allegedly, it "isn't remotely unpleasant" because there is no gross scent after all this time and it's basically exactly like compost. By analyzing what people left behind in their waste, they can know a lot about the food people in Herculaneum ate. It appears they were all ridiculously healthy, with a diet full of seafood and fruit.

Some lucky people even got to look at the poo under microscopes, looking for evidence of diseases residents might have had. And the scatological fun may never end. One researcher said looking at everything in detail "would take a lifetime." So thanks for that, Mount Vesuvius.

The composition of Mount Vesuvius doomed Pompeii

Sometimes the saddest parts of an already tragic story are the revelations that those who suffered may have been doomed from the start. Take for example the victims of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, which destroyed Pompeii and most everyone in it in A.D. 79. Because of the geography of the city and the shape and makeup of the adjacent volcanic mountain, the people of Pompeii were essentially, tragically, sitting ducks.

According to Oregon State University, Mount Vesuvius is a stratovolcano, which Science Daily says makes it very steep and prone to particularly volatile eruptions that, per Geology, are of the Plinian type, creating columns of gas, ash, and rock that can shoot up miles into the sky. That then will fall right back down onto whatever is on the ground nearby, beyond just the base of the steep mountain that allows for extremely rapid lava currents made from especially explosive andesite. All of that came to pass when Mount Vesuvius erupted nearly 2,000 years ago, killing tens of thousands of people who couldn't outrun the lava or breathe through the ash and gases.

Mount Vesuvius eliminated another civilization before it destroyed Pompeii

While isolated natural disasters are certainly tragic, the volcanic eruption that ended the lives of thousands in Pompeii is even sadder with the caveat that this disaster wasn't singular. In 2006, according to the New York Times, "The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences" published the findings of a two-year study by Italian and American scientists of archeological dig sites in areas north, west, and east of Mount Vesuvius. The team discovered 3-foot deep beds of ash and pumice that dated to 1780 B.C., indicating a volcanic eruption that predates the destruction of Pompeii by nearly 1,900 years.

The devastation hit as far as 15 miles away from the volcano, much more distant than Pompeii's 5-mile proximity to Vesuvius. Archeologists also found thousands of examples of quick and tragic loss of life in the ensuing but ultimately failed mass exodus of that Bronze Age village. Thousands of footprint tracks leading away from the volcano were preserved, and scientists also found food on tables half-eaten in the haste of fleeing, as well as the remains of livestock left behind and the burned skulls and bones of those who didn't make it out of town in time.

Pompeii didn't only have a volcano to worry about either. According to Smithsonian, a massive earthquake in about A.D. 62 flattened several areas of the city. Pompeii was still in the rebuilding phase when Vesuvius erupted and finished off the city.

The number of people who died in Pompeii is tough to fathom

Breaking down a tragedy into numbers and figures may feel cold and undignified, glossing over the unique humanity of each person who died. But examining a catastrophic event in such a way can also demonstrate the magnitude of a disaster, putting it into numerical terms that while the brain can comprehend, the heart still cannot.

It's common knowledge that a lot of people died Pompeii in A.D. 79 as the result of the eruption of the volcanic Mount Vesuvius. But just how many perished? According to Joseph Jay Deiss' "Herculaneum" (via Time), historians and scientists estimate that of 20,000 residents of Pompeii, around 2,000 of them died, primarily from toxic gases (per History) vented by the eruption (with the rock and ash flows coming along to destroy property and bury everything and everyone). The remains of hundreds of those people have been lost for centuries, possibly forever. Per Atlas Obscura, slightly more than 1,100 bodies have been recovered from various excavations, which has uncovered just three-fourths of the Pompeii city site.

If a volcano didn't mass-kill Pompeii's population, the water may have

About 2,000 Pompeii residents died as a result of the toxic ashes and deadly lava flows that spewed out of the adjacent Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79. However, life in the ancient civilization didn't exactly promise a clean and healthy existence. Had the volcano not killed 2,000 people during that awful August nearly two millennia ago, thousands more may have died from a serious public health issue possibly rampant in Pompeii at the time.

In 2017, according to Live Science, archeologists studying the former site of Pompeii discovered a fragment of a water pipe from a home. Chemical tests turned out a positive result for antimony, a metallic component of which lead is a major element. Lead particles from lead-lined pipes easily and frequently seep into the water. Humans then drink that water and it accumulates in the body, leading to chronic lead poisoning that manifests in kidney damage, neurological issues, strokes, cancer, and developmental delays in babies and children. According to the findings of the study, published in Toxicology Letters, the amount of antimony in the Pompeii pipe contained enough lead that it would have caused immediate effects to those who drank the drinking water, meaning everyone could have suffered from frequent and severe vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration in the short term, and all the other effects of lead poisoning in the long term.

One Pompeii victim's brutal death became dark meme fodder

A man who lived in Pompeii in the first century, and who died in the cataclysmic eruption of Mount Vesuvius, became "internet famous" more than 1,900 years after his horrific demise. According to HuffPost, the remains of an individual who came to be known as "The Unluckiest Man" were found in an excavation of Pompeii in May 2018. Upon first glance at the skeleton in its final state of repose, archeologists surmised that the unknown, unnamed man had successfully escaped the first eruption of Mount Vesuvius only to perish when a giant stone, likely a door jamb (per USA Today), struck him in the head, instantly ending his attempt to flee (as well as his life). Adding to the grisly fascination with the man, which skeletal clues indicate was in his mid-30s and plagued with a bone infection — his head, arms, and upper torso were no longer attached to his body.

Within weeks, according to the New York Times, the rest of the Unluckiest Man was located. More digging uncovered the missing parts about 3 feet below the legs and door jamb. His skull was all there, along with all of his teeth, which indicates the stone did not decapitate or split his body in half. Archeologists came to believe that the Unluckiest Man's death was just like so many others in Pompeii, tragically succumbing to asphyxiation from being overcome by lava.