Yes, Napoleon Bonaparte Did Have A Will. Here's What It Said

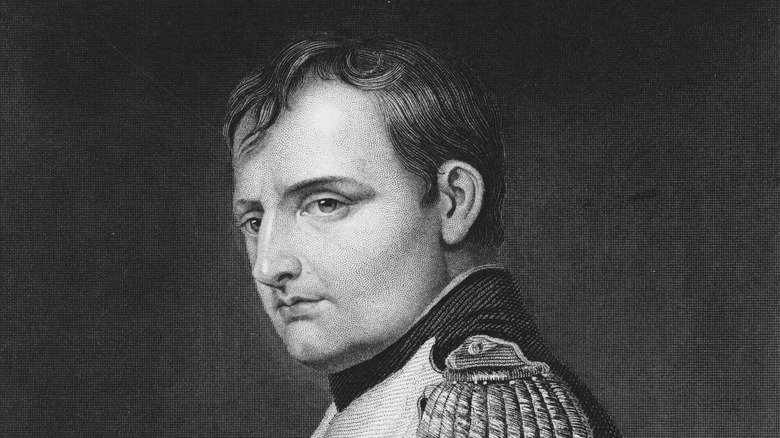

French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte was a man used to imposing his will on the world. Having worked his way through the French military to the role of commander, he established himself as a tactical genius. By 1809, at the age of 40, he had built an empire that overran most of Europe. But it was not to last. By the time it came to writing his last will and testament, he was still just 51, and things had changed dramatically for him. Despite the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe describing Napoleon as a "demi-god" for his dominance during his reign, (via The Economist), in 1815 Napoleon was forced into exile following his defeat to the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo. He spent the final six years of his life in exile on the island of St. Helena, around 4,000 miles from the seat of his former empire in Paris.

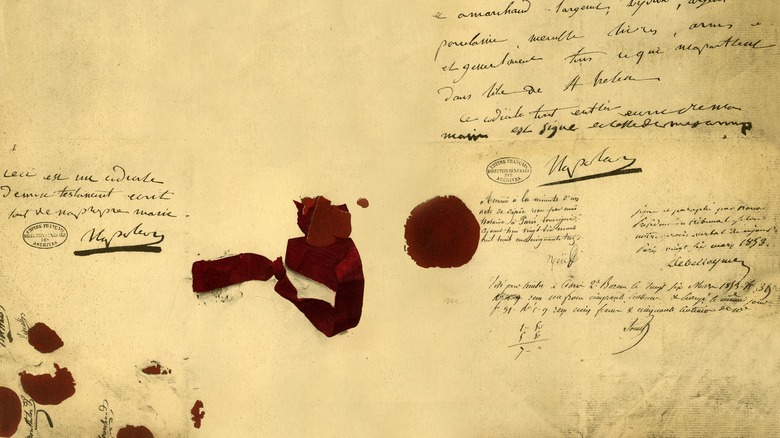

A last will and testament along the lines of Napoleon's is rare today, when such documents are drawn up purely for legal reasons to settle the estate of a deceased family member. The military commender's will is considered unusual due to the huge amount of personal opinion it contains. Indeed, it gives a fascinating insight into his mental state and his view of his achievements, his relationship with France, the actions of his enemies, and his family.

His remains

Outside the academic world of Napoleonic history, few have likely read the entirety of Napoleon Bonaparte's last will and testament. However, many familiar with his death will know his famous opening request regarding his burial, which reads (via napoleon.org): "It is my wish that my ashes may repose on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of the French people, whom I have loved so well."

Napoleon's death in 1821 shook his native France. He retained his popularity as a larger-than-life figure, especially among the hundreds of thousands of veterans of the Napoleonic Wars who were still alive at the time of his passing. And even though he was not universally loved, his loss was keenly felt even among his enemies — particularly the British, who admired him as a military leader. Nevertheless, his request was not immediately fulfilled, with the British governor of St. Helena, Hudson Lowe, refusing the repatriate the former emperor's remains to his homeland. Instead, Lowe had Napoleon buried on the island in the plot pictured above. In 1840, Napoleon's wish was fulfilled when his body was exhumed and returned to Paris.

His family and friends

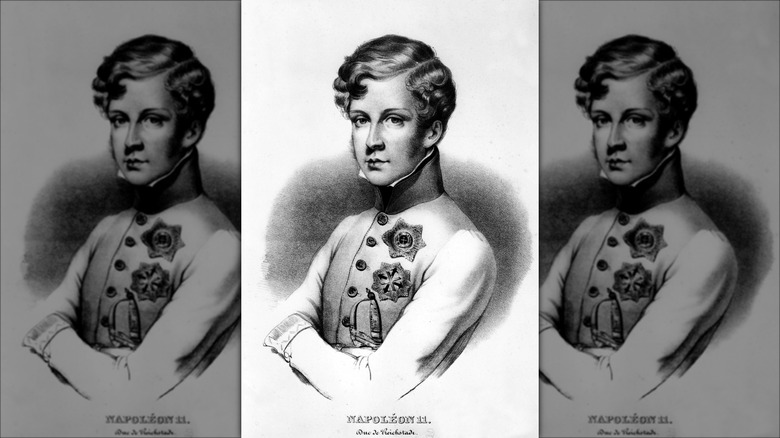

Naturally, Napoleon Bonaparte also used his last will and testament to bequeath his money and possessions to family, friends, and stepchildren. However, he also used the document to share some words with his infant son and heir, the so-called Napoleon II, the Roi of Rome. His son had been estranged from him since his exile.

Napoleon had intended for his son to inherit a vast empire, but after his defeat, all he had left to give him was a collection of boxes and articles such as weapons and clothing. The exiled emperor also had some words of advice (via napoleon.org): "I recommend to my son never to forget that he was born a French prince, and never to allow himself to become an instrument in the hands of the triumvirs who oppress the nations of Europe: he ought never to fight against France, or to injure her in any manner; he ought to adopt my motto: 'Everything for the French people.'"

He entrusted his second wife with enacting his will and the ongoing protection of his son until he was old enough to make his own way in the world. Sadly, Napoleon II son died of tuberculosis in 1832, 11 years after his father, at the age of just 21.

His enemies

Another infamous line of Napoleon Bonaparte's last will and testament concerns his captors, the British, who had exiled him and continued to keep him captive on St. Helena for the final six years of his life. Napoleon had been exiled once before — to the island of Elba following his defeat at the Battle of Leipzig in 1814. But he managed to escape and return to France, where he took power once again. The British, in choosing St. Helena, sought to offer the exiled emperor no chance of making a second comeback.

Napoleon's will reads (via napoleon.org): "I die prematurely, assassinated by the English oligarchy and its assassin. The English nation will not be slow in avenging me." This passage has sometimes been interpreted literally and has reportedly helped give rise to a rumor that the former emperor of France was slowly poisoned with arsenic on St. Helena. However, historians have been keen to point out that Napoleon likely didn't intend to suggest that he was being actively murdered. Rather, the comparatively poor conditions in which he was being kept, severed from his family and nation, led him into a spiral of ill health. The consensus among historians today is that in his final days, Napoleon died of complications of gastric cancer, which would have been impossible to cure even if he had remained in France.

Napoleon also names a number of French military leaders he considered traitors to his beloved country: Marmont, Augereau, Talleyrand, and La Fayette, whom he reportedly blamed for his ultimate defeat.