The Disturbing True Story That Inspired Open Water

Jaws might've broken the mold when it first debuted in the summer of '75, but nowadays shark movies are a dime a dozen. We've since seen L.L. Cool J battle a DNA-enhanced great white in Deep Blue Sea. We saw Blake Lively do her best with a buoy in The Shallows. And who can forget the ridiculous pop culture moment that those so-bad-they're-great Sharknado films enjoyed on the small screen? Chris Kentis' toothy 2003 thriller Open Water was a different kind of entry to the genre, however, as it positioned itself to be based on a true story. And it was! Mostly.

The writer-director was inspired to create the film after hearing the real-life story of Tom and Eileen Lonergan, who disappeared after a scuba diving trip in the Great Barrier Reef of Australia back in 1998. Open Water may have taken some creative liberties with the story because of the unknowns surrounding the Lonergans' fate, but what we do know about their circumstances is even creepier than anything Hollywood could ever come up with. Here's the disturbing true story that inspired Open Water.

Missing in action

Eileen and Tom Lonergan were from Louisiana and had spent time traveling across the world with the Peace Corps. They eventually traveled to Port Douglas, outside Queenstown, and decided to dive among the reefs of St. Crispin on Sunday, January 25, 1998. The two were considered to be "experienced." Their first two dives on the 26-person vessel were without incident, but on the third, they swam away and never came back — at least not before their boat, the Outer Edge, was long gone.

Two heads were missing from the official count before the boat departed from the dive site, but some sources maintain that the number was adjusted up after two people were sighted swimming in the front of the boat, and the crew assumed they'd counted incorrectly. Some reports said the group's bus even alerted the company to the fact that two people hadn't returned, and a boat crew member found some shoes but thought they'd been abandoned unintentionally. It took two full days before anyone truly realized the mistake, once the Lonergans' personal items — including Tom's wallet and glasses — were discovered on the boat by skipper Geoffrey Nairn, who called their hostel and found they hadn't made it back. "I looked in the bag and thought, 'Jesus Christ, it's got a wallet and papers in it,'" Nairn explained to the police. A massive naval manhunt commenced and lasted for five days, but the couple were never discovered in the search.

Washed up

The Lonergans' personal belongings on the boat weren't the only remnants of their fateful trip that would later be discovered. The day after their disappearance, a diver found half a dozen abandoned dive weights at the bottom of the reef, and months later, fishermen found a dive slate with what appeared to be Tom's handwriting and a message containing a date and time shortly after their disappearance — Monday, January 26, 1998, at 8 a.m. — along with a plea for anyone who could help them after being "abandoned" the day before. "Please help to rescue us before we die. Help!!!" it read.

Their scuba vests were later found 100 miles north of where they were last seen and reportedly had no signs of teeth or blood. The items did have tears that were associated with the reefs and barnacle growth, however. A wetsuit much like Eileen's was also discovered with tear marks near the bottom. What was strange, though, was the discovery of their air tanks, which they could have used as floatation devices. Some suspected this meant they abandoned the items after becoming exhausted, but those last items would later become the center of controversy, as folks debated the Lonergans' disappearance.

Dark days

While some people may be inclined to take the Lonergans' disappearance at face value, there were others who believed the two may have staged their own deaths or even committed suicide the day they disappeared, since their bodies were never found. One reason for these conspiracy theories stemmed from Eileen Lonergans' own diary entries, in which she reportedly wrote that her husband had a "death wish."

In one diary entry, Eileen allegedly revealed her fear that her husband might find the "right place at the right time” to take his own life and added, ”I may get caught in that, too. It's a risk I take.” Meanwhile, Tom's own writings seemed to echo her suspicions, as he wrote, "Like a student who has finished an exam I feel that my life is complete and I am ready to die. As far as I can tell, from here my life can only get worse. It has peaked and it's all downhill from here until my funeral." Those texts were only part of the puzzle that surrounded the Lonergans' true fate.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

False witness?

Police also fielded many reports of public sightings of the couple in locations across Australia, and some reported even seeing an unidentified boat in the immediate area on the afternoon of their disappearance. One bookstore owner claimed to have seen them in her shop two days after their disappearance, and another report placed them in a hotel in the nearby town of Darwin.

Diving expert Col McKenzie also thought that they may have faked their disappearance, saying, "Tom was on the pontoon thinking: 'I don't want to go home. We can disappear and start a new life.' I think it's far more likely they're still alive than that they were taken by sharks.” Additionally, a fellow passenger was quoted to overhear the couple tell a crewmember they would "go off and do their own thing." Of course, McKenzie and others may have had a personal financial interest in maintaining the image of the industry, and the owner of the boat, Tom Colrain, was even credited with purposefully fueling these rumors.

Safe harbor

Amid the media frenzy that followed the Lonergans' disappearance, there were many who suggested that the two could have swum to safety. The day of their dive, the sea was described as "glassy and warm," and there may have been places of respite within swimming distance of their drop site, considering their young age, as Tom was 34 and Eileen was just 28 years old. Some speculated that there may have even been other boats to cross the same path at the time.

Others pointed to the placement of a nearby buoy in the area that the couple may have used to stay afloat until rescue could come for them. Although Tom Lonergan may suffered visibility issues and had poor eyesight, Eileen Lonergan wasn't known to have any nearsightedness and would have theoretically been able to see such a buoy if it indeed existed in the area, these claims maintained. A local diver explained, "There was a Quicksilver dive site — a brightly lit permanent platform in the ocean used by divers — that is 2.7 nautical miles from the dive site. It was in the area, if they wanted to go there. There were three or four boats in the area and a dive platform, and they had five hours of light available. There is no doubt that they could have reached one of those. Conditions were excellent." Not everyone was sold on those claims, however.

Proving a point

Understandably, family members who had survived the Lonergans were deeply offended by the spreading suggestion that the two were responsible for their own deaths or had faked them. Tom's mother, Elizabeth, insisted, "I will tell you what the story is: they were left behind. All this talk about them wanting to disappear is just a bunch of garbage — somebody left them in the water and they did not report it for two and a half days."

Meanwhile, Eileen's father, John Hains, took matters into his own hands and went for a snorkeling trip in the same region to confirm that escaping the waters wouldn't be as simple as it may sound. "It's easy to ask, 'Why didn't they swim to safety?' But at water level you can't see anything, and the current wears you out,” he said. He later concluded that it was in the industry's interest to promote these narratives, declaring, "The Australian dive industry wanted to prove that Tom and Eileen faked their deaths. But the survival rate of being in the ocean with no place to go is nil." And he wasn't the only one who had doubts about the alternative explanations.

Official dismissal

The coroner assigned to investigate the Lonergans' disappearance, Noel Nunan, put all those conspiracy theories to rest by officially determining that the two died at sea. "From available evidence it is not possible to say how the couple died but probably by drowning or shark in two or three days after accidentally being left behind," said Nunan. Meanwhile, the case's police investigator, Detective Sergeant Paul Priest, also issued a chilling opinion about the circumstances of their demise by saying, "Being abandoned at sea, being circled by sharks, dehydrating and slowly drowning is not a quick and painless death."

Aside from the fact that it's just the simplest explanation for what happened, the idea that the Lonergans had indeed perished was backed up by other circumstantial evidence, including the fact that their bank accounts were untouched after their disappearance and there were no claims on their insurance policies (which had been a major factor in a previous faked death incident). Priest said he considered the words on the dive tablet to be a "dying declaration," and Nunan dismissed the conspiracy theories surrounding the case as simply "really far-fetched."

Final judgment

Skipper Geoffrey "Jack" Nairn was officially charged with the deaths of the Lonergans in October 1998. The coroner, Nunan, contended that Nairn failed to properly carry out his duty to provide passengers by neglecting to complete the headcount that would have alerted himself to the Lonergans' absence from the boat. If convicted, Nairn faced a sentence of up to life in prison.

Nairn pleaded innocent to the charges and was eventually acquitted in 1999, after offering a defense that included some of the conspiracy theories about the Lonergans potentially faking their deaths. Nairn's extrajudicial punishment was still severe. His career and personal life were ruined by the incident, and he shut down his company after it pleaded guilty to negligence charges. Despite his legal posturing, Nairn seemed to personally take responsibility for the Lonergans' apparent deaths, saying, "It was a tragedy, and I'll never get over it. The highest probability is that Tom and Eileen are dead." Indeed, after his death at the age of 59 in 2016, Nairn's friend Col Mackenzie told the press, "The last time I spoke to him, about a year ago, still at that point he was kicking his own ass. He always, always blamed himself. ... He lost his wife, his business, his money, he lost everything as a result."

Familial fallout

Although Nairn was not completely off the hook for his part in the Lonergans' fate, family members were still disappointed by the result in court — particularly when it came to the defense's decision to parrot those conspiracy theories and use the Lonergans' personal memoirs as proof. John Hains told the Guardian, "The defense attorney used these diaries to absolutely slander, to absolutely destroy these two people's reputations," adding that he felt that swayed the jury because they "didn't believe that they were dead [which was] the essence of the trial."

At the same time, Hains also recognized that the skipper wasn't solely to blame. In 2004, he told the New York Times of the verdict, "For the captain to have taken the full load would have been an injustice. But I would have liked to see some way for a group to be held responsible.” Even then, though, he was still upset by the lingering conspiracy theories.

Industry changes

After the Lonergans' story become international news, the Queensland area diving industry came under intense public scrutiny. Col McKenzie told Brisbane Times, "I don't think we ever will recover from it totally. ... What that said to the dive industry is that if you want adventurous diving, go somewhere other than Queensland." Instead of heading down under, he maintained, tourists were taking their business to other areas in Asia.

Subsequent investigations still turned up some troubling irregularities to justify that fear, though. The Guardian reported that in 2002, a safety crackdown revealed that among 59 dive shops in the area, more than six dozen citations were issued for improper procedures on headcounts and related safety issues. More stringent policies regarding headcounts were eventually put into place to ensure their fate wouldn't be repeated. The Lonergans may have prompted this stricter government oversight of diving safety procedures, but they weren't the last people to be left stranded at sea — in 2008, another couple found themselves in a similar situation after being abandoned by their dive boat, but luckily for them, they were rescued by helicopter after an overnight search.

Making a movie

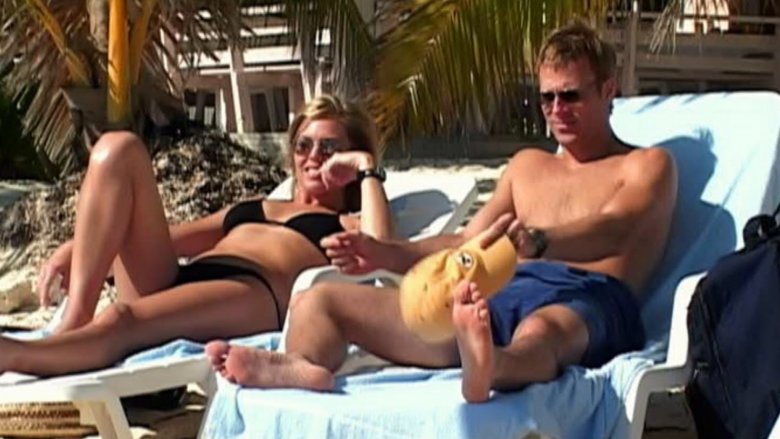

Open Water writer-director Chris Kentis read the story of the Lonergans in a scuba magazine and was inspired to create the film alongside his wife based on the premise of their disappearance. Kentis told National Geographic, "The fear of being left in the open water is an extremely frightening feeling. We were both attracted to the simplicity of that story." However, Kentis didn't want his dramatization of events to be hurtful to the Lonergans' loved ones, so his research about them stopped at the public accounting.

In an interview, he explained, "I did no research on those people, and I didn't want to represent their relationship or their lives. We changed the names, and we invented our own characters because their personal lives had nothing to do with the story I wanted to tell — and also, out of respect for them. We also wanted to leave the exact setting of our movie ambiguous because we didn't want to lay that trip on anybody's tourist trade." The movie was made on a shoestring budget during weekends and holidays but would go on to secure post-Sundance distribution at Lionsgate, earn $54 million worldwide, and spawn two sequels: Open Water 2: Adrift and Open Water 3: Cage Dive. Despite Kentis' efforts to be ambiguous, the film still brought public attention back to the story of the Lonergans.

A rude awakening

The debut of Open Water reopened some still-healing wounds to the diving industry in Australia, so there were some who did not welcome its release. Nairn himself told the Guardian, "The reality of it is that the thing creates emotional turmoil for all of the people involved. It's incredibly unsettling and stressful for myself and my children, and for us it's a terrible thing that [Open Water] has been made. This is really very bad for the industry as a whole." Diving Equipment & Marketing Association exec Tom Ingram echoed those fears by telling E! Online of the movie, "We are concerned that it's going to have an impact on people and families who are going to consider taking up diving this summer."

Eileen Lonergan's father, however, was ultimately glad the movie was made. Although he initially indicated he wouldn't see Open Water, he later screened the film and said it brought him some peace. "For me, this film provides a definite amount of closure," he told E! Online. "It partially fills in a gap which I imagine a body and funeral must normally satisfy. I say partially because, obviously the film is pure speculation, and Eileen and Tom's fate is known only to them."