The Demon Cult Isn't The Scariest Thing About Hereditary

Writer-director Ari Aster's 2018 debut feature film Hereditary is the horror movie equivalent of a haymaker punch to the gut. Following a debut at Sundance, Hereditary's trailer was heavily buzzed about (in no small part because one theater accidentally played it before Peter Rabbit), and soon critics were dusting off the old "scariest movie since The Exorcist" chestnut that anyone that doesn't know how to write about horror trots out whenever they see a good horror movie. Setting aside the completely subjective nature of what's scary and what isn't, Hereditary's acclaim didn't end with comparisons to one of the most beloved spook flicks of all time: It ultimately earned the highest score on Metacritic of any horror movie of 2018, indicating universal acclaim from critics. It's only the somewhat abysmal D+ rating from CinemaScore (garnered from puzzled movie viewers) that kept Hereditary from being unambiguously the best horror movie of 2018.

A lot of elements contribute to that acclaim: stunning performances (especially from Toni Collette and Alex Wolff), beautiful cinematography, and a whip-smart script that demands attention and rewards repeat viewing. Oh yeah — and it's scary as all get out. What starts as a taut family drama quickly descends into a shocking series of tragedies that seem to come at the hands of an insidious cult devoted to a King of Hell. But what is it about this story that frightens us, the viewer? Is it Paimon and his followers, or is it something else?

Spoilers follow, so if you haven't seen Hereditary, maybe move on. It's not worth losing your head over.

Cultists, cultists everywhere

For better or for worse, one of the most memorable scenes (but not, like, the most memorable; everyone knows what that one is) in Hereditary is the closing scene in the treehouse, in which Peter, now housing Charlie/Paimon's soul, is crowned the King of Hell on Earth and a bunch of old people with their ding-dangs out bow down to him. For the kinds of viewers who contributed to that D+ CinemaScore, this ending might seem to have come from nowhere, a weird conclusion to a movie whose trailer seemed to promise that it would be about a weird little girl. But to viewers who paid close attention — who read the literal writing on the walls — this scene was the culmination of every single frame of the film up to that point, a testament to the secret machinations of the cult of Paimon.

Throughout the whole film, the cult has their fingers in every pie: from the funeral to Charlie's death to Annie's desperate spiral into spiritualism to Peter's utter mental and physical collapse, and — as we learn — stretching back even generations before the events of the film, leading to the deaths of Annie's father and brother and even the births of her children. From the shadows, they almost infallibly manipulate everything that befalls the Graham family until all that's left is Peter's broken shell with a demon filling. But why should we be afraid, apart from the film's shocking imagery? What's to fear? Demons aren't real, right?

Wait ... is Paimon real?

It turns out Paimon is real

Well, Paimon is as real as any demon is real, which depending on your personal worldview could range anywhere from incredibly, palpably real to not even remotely real at all. But he's as real as, say, Belial or Astaroth or any of those demons formerly tamed by King Solomon and currently punched by Hellboy, and he's got the credentials to prove it: As Den of Geek lays out, Paimon appears in the 16th-century grimoire known as The Lesser Key of Solomon, arguably the most influential work of demonology of all time, as well as several other notable works on summoning demonic aid.

According to the Lesser Key, Paimon is a King of Hell who wears a crown and rides a dromedary camel, preceded by the sound of trumpets. If you invoke him, he can grant you knowledge of all arts and sciences and secret knowledge of the Earth, wind, and waters. Furthermore, he can grant you good familiars (mentioned specifically in Hereditary) and dignities and lordships, as well as revealing hidden treasures (conveyed as great wealth in the movie).

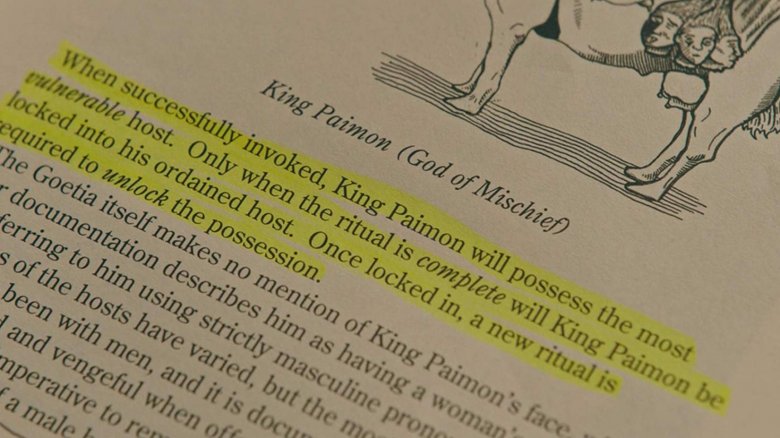

Writer-director Aster goes to some pains to be accurate in his depiction of Paimon, though he embellishes in a few places. For example, the idea that Paimon requires a male host seems to be an original idea, though Paimon is sometimes described as having a woman's face, so gender issues are not out of nowhere. But is Paimon out of nowhere in the movie? What are signs of his presence?

Sign of the demon

Fortunately, Bloody Disgusting has prepared for you a list of the signs of Paimon present throughout the film, in addition to numerous other elements of foreshadowing and signs pointing toward Hereditary's inevitable conclusion. One of the biggest clues to Paimon's presence is his symbol — which, incidentally, is an authentic symbol of Paimon from demonology, not made up for the movie — which can be found lurking in many crucial scenes. Annie and her mother are both seen wearing necklaces with the seal of Paimon at the (first) funeral, with Annie's no doubt a gift from her mother. Once Joan is revealed as a cult member, you can see Paimon's seal on her wall. It's on the cover of some of Ellen's books, and so on. Most significantly, though, you can see Paimon's seal carved on the utility pole where Charlie will later be decapitated, showing how even this seemingly senseless tragedy was in fact orchestrated by the cult of Paimon.

Then there are the necromantic formulas written on the walls throughout the Grahams' house: satony, zazas, liftoach Pandemonium. It definitely helps to be in a dark theater to be able to see these invocations, but just in case, Joan yells them at Peter near the end of the movie. The most literal sign of Paimon's presence, however, is the glimmering blue light that indicates he is manipulating events: Besides the obvious moments of possession, close viewing will catch this light knocking over Annie's paint bottle and popping up during key events at Peter and Charlie's school.

The invisible hand

Despite Paimon's finger being in every pie (or chocolate cake) and the cult's soft, fleshy, nude bodies lurking around every corner, there's one character in Hereditary whose presence is the most pervasive in the film despite being literally defined by her absence: Ellen Leigh, Annie's mother and Peter and Charlie's grandmother.

Ellen is the catalyst for everything in the movie, from any angle. As a leader in the cult of Paimon, her desire to provide a host for her demon king is the driving force behind the shadow conspiracy that wrecks the Graham family. Likewise, her death and the complicated feelings this stirs up in Annie lead to a lot of the emotional conflict in the film. But going back even further, it was her treatment of Annie as a child — the keeping of secrets, the contention between them caused partially by Ellen's involvement in the cult and maybe partially by untreated mental illness — that teaches Annie how to deal with her own children, a lineage of abuse and poor communication that culminates with Annie's explosion at the dinner table.

More than any demon or cultist, it's Ellen's toxic presence that leads to the ruin of three generations of a family. Her lifetime machinations lead to the film's most tragic events in a practical sense, but it is her emotional abuse of her family that creates the emotional environment that makes the family's total dissolution possible. But what is it that makes a grandma a scarier proposition than a King of Hell?

Pay attention in class

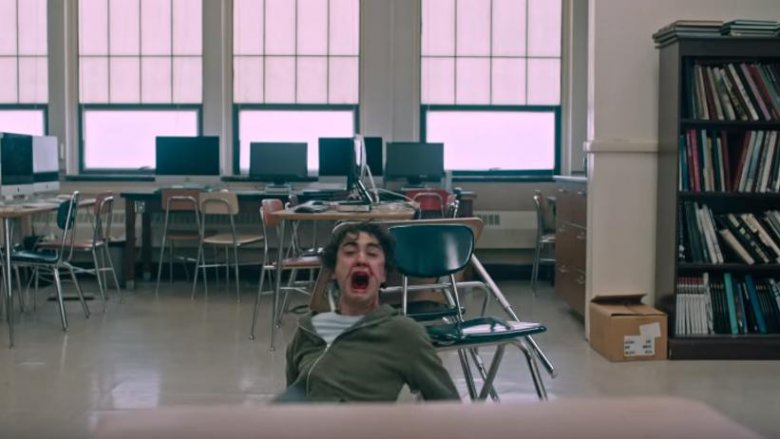

As you hopefully learned from It Follows, if a scene takes place in a classroom, you should pay attention to the lecture because there's a good chance the teacher will say something thematically relevant. In It Follows Jay hears a recitation of T.S. Eliot's "Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock" while discovering the terror of her own inevitable mortality, and Hereditary's Peter sits in on no fewer than three classes where the movie's theme is, in some cases, literally written on a chalkboard.

The final classroom scene has only a snippet of discussion of Aeschylus' Oresteia (a trilogy of plays about the cycle of intergenerational violence) with the words "Punishment brings wisdom" somewhat ominously written on the board, and a history class discusses the Great Depression, which is, seemingly, reflective of the, you know, great depression Peter suffers after Charlie's accident. Sometimes things are just that straightforward. (Is the decapitation motif meant to echo the fear of a loss of self due to succumbing to violent mental illness, i.e. losing your head? Man, maybe.) However, the first scene is the most telling. Peter's English teacher is discussing Sophocles' tragedy Trachiniae, aka Women of Trachis, while Peter texts his friend about weed. The discussion centers on how the tragedy of the play is heightened by Heracles' futile attempts to escape his unconditional fate and how his attempt to control his destiny is an arrogance that is his fatal flaw. Unfortunately, this was an English class Peter and his mom probably should have paid attention to.

A doll's house

One of the most striking elements of the movie is Annie's miniatures. Annie is a fine artist whose chosen medium is miniature replicas of moments in her life. As the film goes on, it becomes clear that these tableaux are representations of emotional and even traumatic moments in Annie's life that she uses to try to process her feelings toward these moments: her mother's funeral, her mother's bizarre behavior in her final days, Charlie's death, and so on. In one of the movie's blackest, most absurdly comic moments, Annie defends her choice to make a miniature of Charlie's death scene to her husband Stephen by telling him, "It's a neutral view of the accident!" Clearly creating an objective third-person view of these terrible moments is Annie's attempt at exerting some control over these things that made her feel powerless; by stripping the scenes of subtext, she can hope to finally understand the text of them.

But as Aster tells Variety, this is at best an illusion of control. The constant framing of the Graham house in such a way that it often becomes impossible to distinguish real house from miniature house is no coincidence; the Grahams themselves are merely dolls living in a dollhouse, puppets whose strings are held by Ellen, by Paimon, by the cult, by fate itself. Like Heracles in Sophocles' play, as Aster says, "any control they try to seize is hopeless." This, or at least Peter's classmates would so assert, makes the fall of the house of Graham all the more tragic.

Lamb to the slaughter

Aster describes the story of Hereditary as "a story about a long-lived possession ritual told from the perspective of the sacrificial lamb." From the very first frame of this movie, Peter is manipulated by others toward his fate, by his grandmother's machinations, by his mother's emotional abuse, by a literal demon, and even by his teachers, kinda (pay attention to the cult members in the final scenes; if you can look away from their pasty dad bods, see if you can see any familiar faces), led like an unwitting lamb to slaughter, until he is physically and emotionally broken down enough to be receptive to Paimon's possession. In another sense, we the audience are lambs as well, ignorant as the Grahams are, thinking we are watching a simple family drama unfold unless we catch on to the clues that they themselves overlook. We are led along ourselves until it's too late to turn back.

Not to break out the "L" word, but this movie is Lovecraftian in the sense that it examines regular people who find themselves confronted with forces so beyond their everyday comprehension that facing it head on destroys their sanity and ultimately their lives. Paimon's logic is not human logic, and any attempts to impose such logic on the tragedies befalling the Grahams has disastrous consequences. And while Peter is Paimon's main focus, no one suffers the consequences of trying to control fate more than Annie.

The illusion of control

The obvious question to ask over the course of the movie is, "Has Annie lost her mind?" Her psychiatrist husband seems to think so, as we even see him drafting an email to a colleague about Annie's possible breakdown. Mental illness, we hear, runs in her family: her mother suffered dissociative identity disorder, her father starved himself to death, and her brother committed suicide in an apparent schizophrenic episode. But within the literal reality of the movie, it's possible most of these diagnoses were misunderstandings of demonic activity (an ironic reversal from much of history). Annie's brother, the original Charlie, was at least telling the truth. His mother was trying to put someone inside him.

Annie isn't suffering a breakdown; she's reacting to literal reality around her. In fact, the least rational thing she tries to do is impose logic on an illogical world. Her attempts to impose order and save her family only make things worse. She tries to contact Charlie to soothe that pain (unaware the degree to which she had been manipulated by Joan) and summons Paimon's loose spirit into their home. The worst example of this, however, comes when Annie tries to have a grand redemptive moment by sacrificing herself for her family by throwing the notebook into the fire, expecting it to consume her. Of course, her husband is burned to death instead; and why wouldn't he be? Why should Annie catch fire this time just because she did before? Paimon's logic is not human logic.

The things we carry

But while the presence of mental illness within the literal reality of Hereditary is ambiguous at best, it is impossible to deny the looming shadow it casts over the film on a metaphorical level. The mental illness passed down from Ellen to Annie and her brother and then to Peter and Charlie is merely one element that moves from generation to generation. As Bright Lights Films puts it, "Something hereditary is passed down to posterity, all without their foreknowledge or approval; an unborn child has no say in what color eyes it will have, what its allergies may be, or what its baseline personality or predispositions will be." Likewise, Ellen's emotional abuse is passed on from mother to daughter, despite Annie's best attempts to remove herself from it, even trying not to have children at all. The keeping of secrets and issues communicating (consider how often Annie lies to Stephen about "going to the movies" and such) also cross generational lines.

Ultimately Peter bears the brunt of all this pain, the way that mental illness, abuse, and intergenerational trauma ate his family from the inside. As Aster tells Vox, the movie is about "how trauma can utterly transform a person, and not necessarily for the better." While that transformation is literalized for Peter and Charlie, obviously not everyone ends up with a crown on their head and naked high school teachers bowing and hailing them. That, uh, that may actually be a good thing, in retrospect.

There are things we can't escape, and things we can't control

"You can choose your friends, but you can't choose your family," or so the saying goes. You might not believe in fate; you might not believe in demon cults manipulating your life. You might fully believe in the pure existence of free will and that we as humans choose our own destinies. But there are some forces that determine facts about us completely outside our capacity to choose: our DNA and the traits derived therefrom, the traumas we inherit from our families, the scars they put in us. Even if you fully abandon your family, cutting them off entirely, you still carry them with you, in your genes and in your neuroses. Sophocles says you can't escape your fate; as Rappler points out, Hereditary says you can't escape your family, and the difference between those two things may be negligible.

More than the devastating terror of the idea of being responsible for the death of a loved one, more than the fear of the ghost of your grandmother or dead sister lurking in the corner, more than multiple decapitations, the scary thing about Hereditary is that there are things in our lives that, despite our most fervent wishes, we absolutely cannot control. Our loved ones will die. Our loved ones will change. We are destined, in one way or another, to become our parents. It is impossible for any of us to ever truly know someone. And all these things are terrifying. The scariest thing, perhaps, since The Exorcist.