14 Unsolved Murders From 1940s America

Unsolved murders generate a morbid fascination — and the more gruesome they are, the more attention they get. Although crime was generally low in the 1940s, America still witnessed a handful of unsolved murders, particularly after World War II. Almost all the cases fell into one of two categories: post-war murders of mostly younger women — when crime spiked following the return of soldiers from World War II — or gangland hits involving organized crime.

To put the murder statistics in context, according to data from the American Historical Association, homicides dropped steadily from the 1930s, except for a 0.2% increase from 1940 to 1941. After 1941, many young men, who generally commit the most violent crime, were shipped off to fight in World War II. Like clockwork, crime ticked up again in 1946, when millions of deployed men returned to the U.S. Thus, many of the unsolved murders of the '40s hit the news because they were such anomalies, not just in their occurrence and seeming randomness, but in their brutality and the widespread fright they generated. Here are some of the better-known cases.

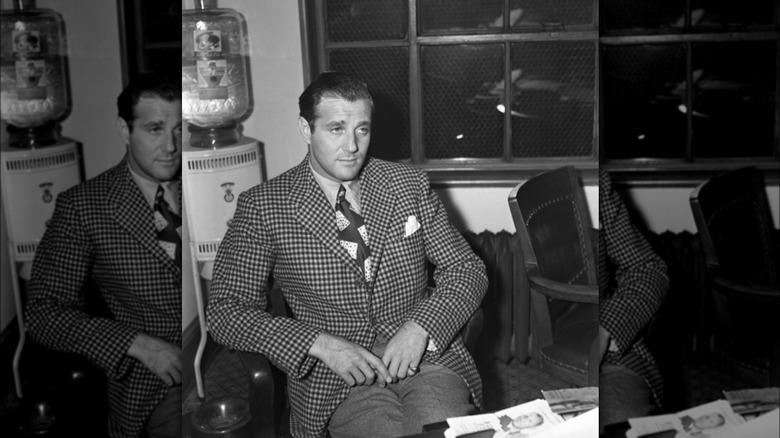

Killing of Bugsy Siegel

Murder, Inc., gangster Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel made his fortune off the usual rackets of bootlegging, prostitution, and murder-for-hire. In a more bizarre venture, he also tried to sell an explosive known as atomite to Benito Mussolini's Italian military. But for all his fame, no one knows for sure who gunned him down in Beverly Hills, California, in 1947.

Siegel was in California to conduct business and enjoy a vacation with his daughters, who lived with his ex-wife Esta. After dinner with a handful of friends and business partners, Siegel returned to the house of his mistress Virginia Hill, who had left for Paris after an acrimonious fight. There, a gunman shot him twice in the face and twice in the chest. Police struggled to narrow down the suspect list due to Siegel's many enemies. He had construction debts related to his casino and East Coast kingpins like Salvatore "Lucky Luciano" Lucania hated him, as did Virginia Hill's family for mistreating her.

The hit's lead suspect was Murder, Inc., honcho Meyer Lansky. In 1947, an FBI informant claimed Lansky had identified the killer as Virginia's brother Chick. Robbie Sedway, son of Siegel's bookkeeper Moe Sedway and his wife Bee, told LA Magazine in 2014 that his mother's lover, Mathew Pandza, killed Siegel before Siegel could kill Moe. Moe had reportedly put Siegel in a bad position by telling Lansky about Siegel's financial issues. It seems Lansky was happy to see Siegel go — one way or another.

The strange death of Vera West

Fashion designer Vera West, who worked on now-classic Universal productions such as "The Bride of Frankenstein" and "The Killers," was found dead in her pool by photographer Robert Landry in 1947. Police also found two notes addressed to one "Jack Chandler," reading, "This is the only way. I am tired of being blackmailed," and "The fortune teller told me there was only one way to duck the blackmail I've paid for 23 years — death," according to The Vintage Woman Magazine. A medical examiner determined that she had probably drowned, but the Los Angeles County coroner refused to sign the death report.

The "blackmail" was likely a reference to an unknown scandal that triggered West's move to California from New York in 1924. Suspicion fell upon her husband, Jack C. West, who gave differing accounts regarding his whereabouts on the night of her death. He also claimed there was no blackmail, but said her behaviour had been erratic. Vera's friends, however, suspected that her death was a murder dressed as a suicide.

The investigation was full of holes and unanswered questions. Police never established whether Jack Chandler and Jack West were the same person and never identified the blackmailer or the fortune teller. Suicide also did not explain how the hydrophobic Vera ended up in the pool — she was afraid of even being near it alone. And then the big question: Why did Jack West demolish their house and disappear without a trace? The case is widely considered "cold" due to these inconsistencies.

Elizabeth Short, aka the Black Dahlia

The body of Elizabeth Short, dubbed the "Black Dahlia," was found in Los Angeles in 1947 by a mother walking with her child on the street. Short had been brutally murdered — according to an LA Times report from that year (via the FBI), she had suffered blunt-force head trauma, had her mouth slit, and been cut up.

The troubled Short had left Massachusetts for California as a minor, where she was arrested for underage drinking in 1943. By 1947, she was a regular at Hollywood nightclubs and other fancy joints. According to local resident Vera French, who had taken Short in at one point, she had amassed a laundry list of suitors and boyfriends.

French said one of Elizabeth's exes had reportedly threatened to kill her for moving on to other men. Los Angeles Police Department officer Myrtle McBride gave an account that agreed with French's, adding that a girl resembling Short had approached her on the street for help with a violent ex, although McBride was not able to identify her with certainty. The case is still cold, complicated by bizarre false confessions and no FBI fingerprint matches to the suspect. However, observers noted that whoever cut up her body likely had medical training. In 2016, retired Los Angeles police detective Steve Hodel told The Guardian that his father, Dr. George Hodel, had done it, although it is impossible to say for sure, since much of the original evidence is gone.

The Van Camp farm murders

In 1940, farm worker John Verkuilen made a grisly discovery when he found the bodies of his boss William Van Camp and Van Camp's 77-year-old mother Annie dead in their farmhouse in Little Chute, Wisconsin, per the Appleton Post-Crescent. According to the report, it appeared the mother of seven and her youngest son, who ran the farm, were preparing for bed when William heard an intruder on their porch. He went to investigate and was shot in the face with a 12-gauge shotgun. The killer then made their way to Annie's room and shot her in the face too, so soon after killing William that it seems she did not even have a chance to react to her son's murder — assuming she was aware of it.

Authorities reported finding an empty leather sack on Annie's dresser, suggesting robbery was the killer's motive. Unfortunately, police investigations came up empty after interrogations of a handful of suspects failed to link anyone to the available evidence. Part of the reason may have been that Van Camp relatives disturbed the crime scene, according to a 2013 Post-Crescent interview with family members, leaving little intact evidence that the authorities could definitively link to the crime outside of the bodies and the purse. After 1945, the original case file was lost, making it difficult to reopen the investigation, barring someone coming forward with a confession. That is unlikely, since the murderer is probably dead.

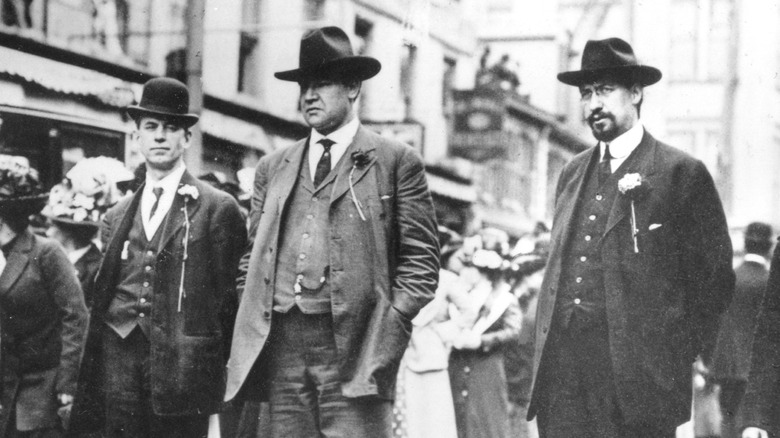

Carlo Tresca

Italian socialist and journalist Carlo Tresca (above left), an acquaintance and fierce critic of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, was gunned down in New York City in 1943. At the time of his death, people suspected everyone from Mussolini and Italian fascists, who had a warrant out for him, to American communists — he had that many enemies. But in mid-20th-century New York, where there was murder, there was often Cosa Nostra. True to form, future Bonanno Family boss Carmine Galante was believed to be the shooter (he was but an ex-con at the time), per Dorothy Gallagher's "All the Right Enemies."

Galante spent some time in jail as a suspect but was released without charges, so the case was never closed. But Tresca was likely the victim of an alliance between fascist Italy and Cosa Nostra kingpin Don Vito Genovese. Tresca had stymied Mussolini's activities in America for years. Despite his anti-mafia campaign during the 1920s, the Italian dictator had become close to Genovese, who functioned sort of like Mussolini's American fixer. So when Tresca hindered Mussolini's designs among Italians in America, he also ran afoul of Genovese. Tresca also allegedly had threatened the don with exposure of a drug ring he ran out of Italy.

Thus, it would seem Genovese had Tresca killed, both out of self-interest and as a favor to Mussolini. Salvatore Lucania, better known as "Lucky Luciano," quipped in 1961 that when Mussolini had a problem, Genovese would "take care of it" for him. One of those problems, Luciano said, was Tresca.

The Texarkana Moonlight Murders

The Texarkana Moonlight Murders were two double murders and one single murder that took place near Texarkana, Texas, between March and May of 1946. Teenagers Richard Griffin and Polly Anne Moore were removed from their car, shot in the head with a .32 revolver, and put back inside the vehicle. A second pair of teens were dragged out of their car and shot with the same caliber weapon the following month. A third murder hit the news in May, when Virgil Starks was shot dead in his home; his wife survived with two bullets to the face. In Starks' case, the killer used a .22 but left similar tire tracks at the scene.

Police concluded the crimes were related. A third couple, Jimmy Hollis and Mary Jeanne Larey, who survived a similar attack in February, reported an assailant wearing a burlap sack and armed with a gun, likely a pistol, which he used to whip Hollis. Like at least one of the murdered women, Larey had also been sexually assaulted — another detail the attacks had in common.

The killings caused panic in Texarkana. Gun sales skyrocketed, while women reportedly took their children to hotels whenever their husbands were out of town. Police never confirmed the killer's identity, but Texarkana native and author James Presley, nephew of the Bowie County sheriff who investigated the murders, told Texas Monthly that the killer was likely a man named Youell Swinney, who was incarcerated on car theft charges in 1947. The case, however, is officially cold.

Oliver Springs murders

Ann and Margaret Richards were two white sisters and granddaughters of local Tennessee hotel mogul Joseph Richards. The sisters, along with Leonard Brown, a Black teenager who worked for them, were inexplicably murdered in their Oliver Springs mansion in a cold-blooded killing in 1940 that brought together crime and race in the Jim Crow South.

Initially, per WBIR-Knoxville, law enforcement suspected Brown of killing the sisters in a murder-suicide. The killer had positioned the gun to make it seem like Brown had killed himself after shooting the women. Witnesses added that Brown had left the house of the family that allegedly owned the murder weapon the same morning, suggesting he had stolen the gun. On this explanation, the sheriff closed the case and declared Brown the killer. Despite the closure, there were doubts. Brown was known as a good kid who was afraid of loud bangs. He had also been shot in the forehead from above — an unlikely place and trajectory for a supposedly self-inflicted gunshot wound.

In 2000, a man reported seeing two other men leaving the mansion on the day of the killing. After the men threatened him, the witness skipped town. With his testimony, law enforcement exonerated Brown and tied the killing to a property dispute the women had with their cousin, Mary Sienknecht, who had lost a property case against the pair in court years earlier. But all the suspects are dead, including one suspect who was shot to death by another, reportedly to prevent him from talking to police.

Georgette Bauerdorf

Oil heiress Georgette Bauerdorf was found dead in her bathtub in 1944, wearing only her pajama top. The Tuscaloosa News reported the Los Angeles Police Department initially suspected an accident because her valuables were untouched, apart from a missing $100. However, they realized she had been murdered after finding a medical bandage stuffed down her throat. The Los Angeles Times reported on further examination that her body was bruised, her skull punched in, and her knuckle bones shattered — she had put up a fight.

Police searched Bauerdorf's personal life and diary for clues. The journal contained the names of different soldiers she had been involved with, so suspicion fell on them. Police suspected Cpl. Cosmo Volpe, who was witnessed aggressively pursuing Bauerdorf and getting in between her and other men on the dance floor at the club where she worked, but released him after his alibi — that he had returned to barracks before the murder occurred — checked out. Sgt. Gordon Aadland, the last person to see her alive after he hitchhiked a ride with her, was also exonerated after questioning, according to his own account in The Centralia Daily Chronicle.

The biggest clue to determining her killer may be the medical bandage found lodged in her throat, which, according to author Steve Hodel, citing contemporary newspaper reports, had not been available to anyone except for doctors since the 1920s. Hodel has suggested that the killer must have been a medical professional, similar to whoever had murdered and dismembered Elizabeth Short — perhaps his own father, George.

Shooting of Prof. Lewis Allyn

Professor Lewis Allyn was a "pure food" activist and college professor who was murdered at his house in Westfield, Massachusetts, in 1940. He lived in a respectable home with his wife, ran a lab, and taught classes at what is today Westfield State University. One night in May, after an argument with an unidentified person at his door, Allyn was shot twice in the face and twice in the body. His killer was never caught.

Sensational theories surfaced to explain Allyn's killing, accusing everyone from Nazis who wanted his patents for food preservatives to the food industry for his promotion of "pure food" standards, and even the mafia, which had supposedly targeted Allyn for being a government informant, per Westfield historian Bob Brown. However, according to Brown, none of these had any basis in fact. They were grand conspiracies that sprang up amid intense national coverage after law enforcement failed to solve the crime.

Brown hints at two alternative possibilities. Allyn appeared to have a reputation as a womanizer, potentially even having relationships with his female students. Given that the murder began with an argument, it is possible Allyn ran afoul of a father, husband, or boyfriend of one of these women, and was killed in a crime of passion. Alternatively, he may have been killed in relation to his finances, perhaps by someone who was owed money or had lost money investing in a company Allyn had promoted. Either way, the killing remains unsolved 83 years later.

Margaret Treese

Margaret Treese was a war widow and divorcee who appeared to have moved to Iowa after divorcing her second husband in West Virginia. In 1947, two workers found her dead one morning in a Davenport, Iowa, park. According to the Estherville Daily News (via Iowa Cold Cases), she was found naked, badly disfigured, and covered with tattoos, leading her case to be dubbed "the Tattoo Murder Case." Her killers had shown no mercy, stabbing her at least 10 times and even running her over with a car.

Police quickly turned their attention to Treese's social circles, which included a handful of men with whom she appeared to have been romantically involved, per a Spokane Daily Chronicle report on the case from 1947 (via ICC). Treese was also known as a regular at the taverns on Davenport's skid row.

Witnesses said she was last seen outside a bar on skid row getting into a car with three men. In 1956, however, the Cedar Rapids Gazette (via ICC) reported that an unidentified woman, who described herself as Treese's acquaintance, had seen her just a few hours before her death in a car with two men. According to the news report, both men were "known police figures." Police never ascertained a motive and no one was ever charged. The perpetrators are likely dead.

Pete Panto

The Brooklyn waterfront of 1930s New York was a haven of mob activity. According to Tom Folsom's "The Mad Ones," mobsters like Larry Gallo got their starts there, enforcing kickback schemes, roping workers into rigged numbers games, and directing them to mafia loan sharks to pay for the above. Tired of their tactics, Italian longshoreman Pete Panto eventually led a 1,000-man strike against Cosa Nostra in July 1939. He disappeared a week later.

Panto's fate was confirmed in 1941 when his body was found in a New Jersey lime grave. According to a Time Magazine story from 1952, Panto had run afoul of none other than Umberto Anastasio, better known in mafia lore as "High Lord Executioner" Albert Anastasia, who ruthlessly ran the New York waterfront. According to the outlet, New York Mayor Bill O'Dwyer, at the time a Brooklyn prosecutor, had promised to bring the killers to justice. Unfortunately Murder, Inc., hitman Abe Reles, the city's star witness, conveniently took a fatal fall out of a window before trial.

This was, of course, O'Dwyer's account. Time, however, revealed that O'Dwyer had buried a conversation between two of Anastasia's men discussing Panto's killing and directly implicating the capo. Furthermore, Anastasia was never questioned – the first thing any good detective would have done. So although Panto's murder is technically unsolved, everyone knew then and now exactly who was behind it. Corruption and threats likely won the day, and Anastasia lived to contribute his waterfront management style to the U.S. Army during World War II.

Disappearance of Virginia Carpenter

Twenty-one-year-old Texarkana native Virginia Carpenter was supposed to start school at the Texas State College for Women (pictured) in Denton. Instead, she disappeared after a taxi dropped her off in front of her dorm on the night of June 1, 1948.

After Carpenter vanished, police immediately went to the last person to see her: taxi driver Edgar Zachary. He told police Carpenter had met two men in a car at 9:30 p.m. in front of her dorm when he dropped her off. She reportedly knew them and said they were going to help her with her luggage, so he went home. Zachary's wife, however, testified years later that he had not come home until 2 or 3 a.m. If true, there is the question of why he lied. The driver passed all polygraphs, however, and was released without charges.

If Zachary was being truthful, then the men were probably the kidnappers. Their identities are unknown, since all suspects named over the years are dead. There is, however, one more chilling detail that might provide a clue. Carpenter knew three of the Texarkana Moonlight Murders victims, according to The Lineup – a statistically near-impossible coincidence considering Texarkana had a population of nearly 25,000 in 1950. One theory is that the Texarkana killer tracked her down and killed her too. But those crimes were never officially solved either, so it is impossible to know. Carpenter was presumed murdered and declared legally dead in 1955, though her body was never found.

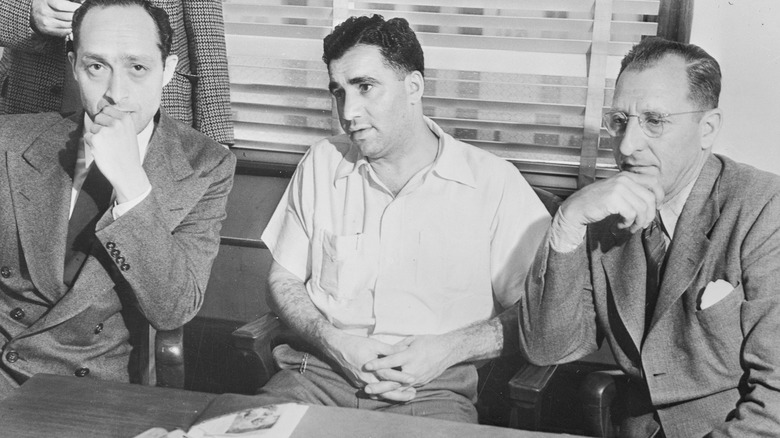

Killing of Whitey Krakow

Walter Krakower, better known as Whitey Krakow, was one of Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel's hitmen who was involved in the 1939 slaying of underworld figure Harry "Big Greenie" Greenberg. According to "Murder, Inc.," by Burton Turkus, a law enforcement officer involved in prosecuting members of the hitman syndicate, Krakow and several other hitmen were involved in ambushing Greenberg as he returned to his California home after an evening drive.

Krakow, however, would not live much longer. Burton writes that the authorities scrambled to get any witnesses and informants into witness protection before Siegel could clip them too. Krakow was one of those people of interest, with Burton suggesting the FBI was willing to offer him a deal if he talked. Unfortunately for investigators, Krakow was gunned down on New York City's Lower East side in August 1940.

Burton writes that Siegel was arrested in relation to all of these killings, especially the Greenberg hit, along with an associate named Frank Carbo, who was also charged with murder. However, Siegel got "lucky." Star government witness Abe Reles (pictured above center), a partner of Krakow, "fell" out a window to his death in 1941, so Siegel's case was dismissed due to lack of evidence. Carbo's case ended in a hung jury, despite multiple witnesses identifying him with certainty as the killer, so he walked too. Thus, although Krakow's murder was probably on Siegel's orders to prevent him from turning informant, officially, his case remains unsolved.

Ferdinand Socha and Joseph Lynch

Detectives Ferdinand Socha and Joseph Lynch were members of the New York City Police Department's bomb squad. They were called to disable a suitcase bomb at the 1939-1940 World's Fair, which blew up and killed them, according to a 1940 Time Magazine report on the incident.

New York City saw a spike in political violence in the 1930s, including bomb attacks, thanks to conflicts between local communists and the German American Bund, a pro-Nazi German American organization. Because the bomb had been found in the British Pavilion (a soon-to-be enemy of Germany), police immediately suspected the Bund, which had also been accused of trying to blow up the Brooklyn Bridge. However, investigations came up empty, despite a $26,000 reward.

Without any clear connection to the Bund, the only suspects left were the British themselves. NYPD officer and historian Bernard Whalen told Atlas Obscura that Hitler was desperate to keep the United States out of Europe to avoid a larger war he could not win. Thus, it was not in the Bund's interest — if they represented the Nazi party's strategy — to carry out attacks against American targets. American public opinion was mostly either pro-German or anti-interventionist, and terrorism risked gutting that. The British, however, wanted American involvement in Europe as soon as possible. According to one theory, it was possible that British intelligence had false-flagged the U.S. with a terror attack on American soil that could be blamed on Hitler's supporters in America. But this remains mere conjecture.