Mafia Stories That Seem Too Wild To Be True

The various Italian mafias generally make the news for their adventures in extortion, racketeering, drug trafficking, murder, and every other type of criminal activity under the sun. Sometimes, however, the stories have gone way beyond the usual criminality into the realm of the wild and sometimes straight-up unbelievable.

Because of the constant police heat and need to maintain members' respect and loyalty, mafia men have gone to crazy lengths to keep their operations running smoothly. Some of them are wild in the sense of "what were they thinking" –- think Paul Castellano's public affair with his Colombian maid or a Neapolitan boss in hiding getting caught because he celebrated his soccer team. On the other end, there are those that crossed the red line, such as bombing Rome's archbasilica or (allegedly) killing Pope John Paul I. And of course there is everything in between. But one thing is for certain — you probably would not believe the stories after first reading them.

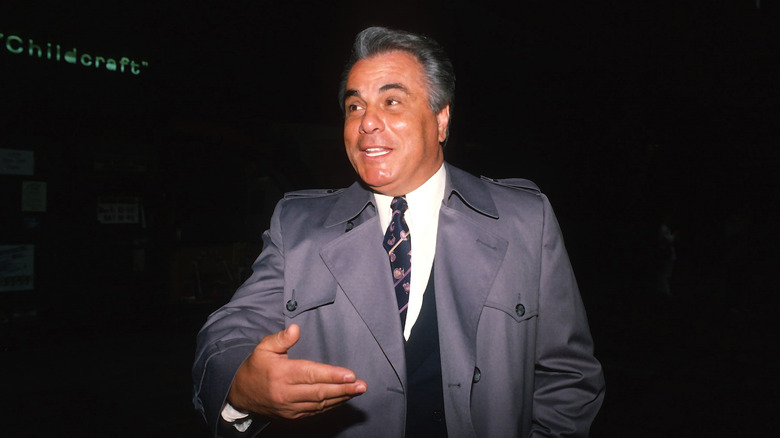

Paul Castellano loses respect over affair

Paul Castellano inherited the Gambino Family from his cousin Carlo Gambino, who died in 1976. As head of what was considered the most powerful crime family, his organization committed murder, extortion, and prostitution, among other crimes. But he equally engaged in legitimate business in industries like construction or meat. He also disliked gratuitous violence and attempted to keep a low profile in his private life. Even so, as with any mafia boss, there was always a target on his back.

Gambino underboss Salvatore Gravano told Valuetainment that Castellano's affair with his Colombian maid, Gloria Olarte, was the final straw that lost him his remaining loyalists. Now, extramarital affairs were the norm among mafiosi. But, dons were expected to maintain a level of decorum and respect for their wives, who were viewed as mother figures, just as bosses were father figures. He was supposed to keep the affair discreet, outside of his own house, and certainly not in full view of his wife and children. Gravano said many of the Gambino men viewed Castellano's humiliation of his wife by his public affair with Olarte as akin to insulting their own mothers.

Gambino family rival John Gotti had Paul Castellano killed in 1985 over disagreements with Castellano's ban on drugs and opposition to street activity in general. But given Castellano's behavior at home, most of New York's other gangsters were happy to sit by and watch.

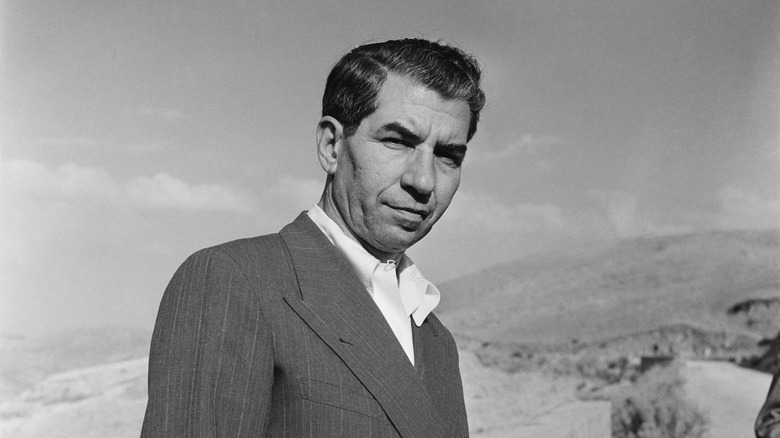

Neil Dellacroce carried out murders dressed as a priest

Aniello "Neil" Dellacroce's name literally means "little lamb of the cross." His parents undoubtedly chose the name in honor of their Catholic beliefs and to provide a template for Dellacroce's conduct. Instead of living up to that name, Dellacroce became Carlo Gambino's underboss and one of the most feared gangsters of 1970s and '80s New York.

Dellacroce's exact criminal record is unclear. Like any good gangster, he avoided the spotlight, but he reportedly carried out numerous murders on behalf Albert Anastasia. In a sick twist, he dressed as a Catholic priest named Father Timothy O'Neill while carrying out hits. When a rival attempted to shoot up the Ravenite Social Club in Little Italy, per Sal Polisi's "The Sinatra Club," Dellacroce's men found the killer by "[sticking] the barrel of a gun down a witness's throat and [listening] to him sing." When the shooter was found, he was dispatched without mercy.

These stories about Dellacroce, crazy as they seem, agree with law enforcement testimonies. One FBI agent quoted in a 1985 Time Magazine article said, "He likes to peer into a victim's face, like some kind of dark angel, at the moment of death." NYPD detective Ralph Salerno agreed, calling Dellacroce a cold-blooded killer and one of only two mobsters who ever frightened him, as per Selwyn Raab's "The Five Families."

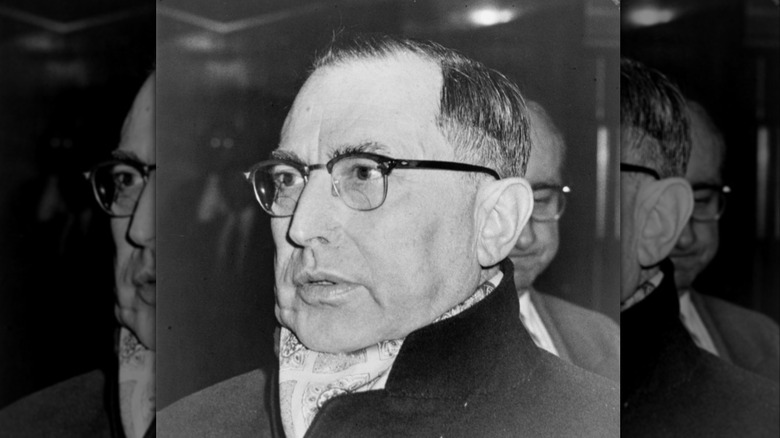

Lucky Luciano meets Meyer Lansky while trying to rob him

Muggings don't usually yield partnerships or friendships, but that's how Meyer Lansky and Lucky Luciano hit it off. According to Robert Lacey's bio of Lansky, "Little Man," the two met when the Jewish Lansky set foot in the wrong neighborhood –- presumably Little Italy –- while walking on New York's Lower East Side. There, Luciano, who led an extortion gang, tried to mug him, figuring that Lansky, like most Jews he had mugged before, would not resist.

Instead, Lansky told Luciano off and refused to give him money. Luciano and his gang, however, respected Lansky' for standing up for himself and let him go. Later, they offered him a deal. Italians and Jews had a common enemy in Lower Manhattan's Irish gangs. The Irish looked down on Jews and Italians, since the former had been in New York longer and had connections with the police, which always took their side. Gangs of Irish teens beat up Jews daily, so Luciano figured they could face them together. Lansky agreed, and a partnership was born.

The partnership survived well into their adult years. Lansky aided Luciano's takeover of the New York mafia in the 1930s with hits on top bosses and cooperated with him on rackets such as bootlegging and gambling.

The Brooklyn Miracle

Brooklyn's Regina Pacis Catholic Church contains a statue of the Virgin Mary with jewel-studded gold crowns blessed by Pope Pius XII in 1952. That same year in May, however, the crowns were stolen. But eight days later, they reappeared in the church mail, without any police involvement.

Four days before the crowns' return, police discovered the body of one Ralph Emmino on a Brooklyn sidewalk with bullets in his head and chest. Emmino was a thief and stickup man, having helped steal $35,000 in gold and platinum in 1947, per mafia historian Thomas Hunt. Police quickly realized, given Emmino's previous reputation, that he had probably been killed for stealing the crowns.

The hunch was confirmed in 1962, when FBI informant Gregory Scarpa said mafia boss Joe Profaci, whom contemporaries described as a devout Catholic (he even had a private chapel in his home) and financial patron of Regina Pacis, was furious at the shrine's desecration. Churches were sacred and off limits, so Profaci sent his men to recover the crowns and kill Emmino in revenge. One of his men then mailed them back to the church in an anonymous package from a Manhattan post office. Monsignor Angelo Cioffi, the pastor of the shrine, announced the crowns' return as a miracle, and Catholic Brooklyn celebrated. Profaci's successors would later arrange the return of the crowns after a second theft in 1973.

American Cosa Nostra puts out a hit on nun's rapist

In 1981, two men assaulted a nun inside the Convent of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel in East Harlem, New York. According to Nicholas Pileggi's biography of New York City cop Bo Dietl, "One Tough Cop," the perpetrators left the gruesome reminder of 27 crosses etched into the nun's breasts and buttocks. The city offered a $10,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of the perpetrators, Harold Wells and Max Lindeman. The attack shocked New Yorkers, who viewed the assault as a sign of New York's degeneration, in which nothing was off-limits anymore.

American Cosa Nostra was also interested in finding the nun's rapist, reportedly putting out a $25,000 hit on both perpetrators. "These were local Mafia chiefs with long Catholic memories who were still capable of being scandalized," Pileggi wrote. Our Lady of Mt. Carmel was an Italian church that served East Harlem's dwindling Italian population. The rape was a violation of sacred space and a sacred person, a big no-go in American mafia culture. After all, Joe Profaci had a guy killed for simply robbing a church.

Regardless of the hit's veracity, just the fear that the hit might be real was enough to scare Wells into compliance. Police arrested him in Chicago, where he confessed to the crime. He and Lindeman were found guilty and sentenced to upwards of 15 and 20 years, respectively.

Vincenzo LaPorta busted by his love of soccer

When mobsters go into hiding in the modern world, avoiding social media, public events, and the cameras is key to not getting caught. Vincenzo LaPorta, however, let his love of soccer get the better of him when he gave away his hiding place on the Greek island of Corfu, after being on the run for 11 years. LaPorta was a member of the Neapolitan Camorra, where he worked as a money launderer. For his activities, Italian authorities hit him with 14 years on tax evasion and fraud charges. At the time, his whereabouts were officially unknown, so he was sentenced in absentia.

LaPorta was not just a mobster –- he was also a megafan of Naples' soccer team, SSC Napoli, which won its first Italian Serie A championship since 1990 in 2023. As pictures and videos of celebrations among Napoli fans from around the world made the rounds on social media, police noticed LaPorta waving a Napoli scarf from the balcony of a Corfu restaurant. "[He] couldn't resist celebrating," Italian authorities told the Associated Press in a statement.

LaPorta was promptly arrested in Corfu after he attempted to escape on a motorscooter –- not the best getaway plan since Corfu is an island. His lawyers told the AP they are fighting extradition to Italy on humanitarian grounds, since LaPorta has established a second family in Corfu, where he has a 9-year-old son.

The Ndrangheta and the Virgin Mary

The Calabrian Ndrangheta is among Europe's most powerful syndicates, raking in billions primarily from drug trafficking. It also engaged in kidnapping for ransom, most famously of John Paul Getty III in 1973. The Ndrangheta maintains close links to the Madonna of Polsi, a Calabrian apparition of the Virgin Mary, carrying out its most important business -– meetings, certain initiations, and resolution of disputes –- near the virgin's mountain sanctuary.

According to Italian authorities cited in an OCCRP report, the Ndrangheta's connections to the shrine run deep. The inner core of the Ndrangheta is known as "the saint. " During the crowning of the Madonna ceremony, police report that mafia gatherings often take place in broad daylight under statues of the Virgin Mary. It is unclear why, but it seems the Ndrangheta considers the Madonna as a sort of protector who blesses their criminality.

The Catholic Church has fought the Ndrangheta's appropriation of the Virgin Mary, removing Madonna statues from public places to discourage Ndrangheta meetings in the sacred area. The church has also banned Ndrangheta members from carrying the big statue of the Madonna during the procession. Finally, processions also may not bless Ndrangheta members by stopping near their houses after one procession "blessed" the house of boss Giuseppe Mazzagatti, who was serving a life sentence under house arrest. Such stops are considered a blessing for criminal activity.

John Faraci tries military service as a get-out-of-jail card

The case of Bonanno hitman John Faraci is quite amusing, in the sense of "did he really think that was going to work?" In 2002, the 79-year-old found himself face-to-face with Judge Leo Glasser -– the same judge who sentenced John Gotti to life in prison –- after a conviction for trying to bribe union officials. Glasser castigated Faraci for not quitting organized crime while he was still ahead. "I suggest at your age ... you ought to be thinking about getting out of that life, worrying about who's coming knocking at your door putting handcuffs on you," the judge told Faraci and his co-defendant, per the New York Post.

Faraci's lawyer, Vincent Romano, said his client deserved some mercy due to his military service. Romano told Glasser that Faraci had served America admirably in World War II during the Battle of Normandy, where he earned a Bronze Star for heroism. It is unclear whether he served in D-Day, but regardless, it did not work.

Glasser had little patience for Romano's excuses. He shut down the lawyer with an epic three-word sentence: "So did I." Faraci, meanwhile, was contrite, or at least tried to pretend to be as the judge castigated him. "I'm sorry I wasted the court's time. I'm sorry I aggravated my family," he said.

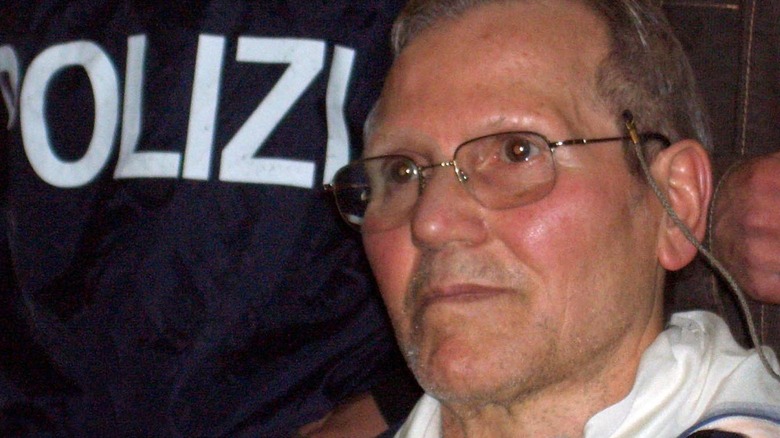

Bernardo Provenzano runs his syndicate with two typewriters and the Bible

Bernardo Provenzano ran Sicilian Cosa Nostra from 1993 until 2006, when he was arrested after four decades on the run. As boss, he eschewed technology, running the organization with two typewriters, a dictionary, and five annotation-packed copies of the Bible.

Upon his arrest, authorities realized Provenzano used a secret code to communicate with his subordinates from his rural Sicilian hideout. He would type notes called "pizzini" and fold them so tiny they fit between people's toes, using a cipher that assigned each letter a number and then added three. Thus, A became 4, B became 5, C was 6, and so on. The role of the Bibles, however, is less clear. Provenzano copied out entire verses in his notes and even seemed to write short treatises on what exactly various keywords meant. He also assigned religiously themed aliases to his subordinates and contacts, per Reuters, referring to one as "the adored Jesus Christ."

Authorities confiscated all of Provenzano's Bibles, including his bedside copy, but have yet to crack the Bibles' code -– if there is one. Provenzano's hideout was decked out with crucifixes and images of St. Padre Pio and he reportedly watched or listened to mass daily. So it is possible his Bible annotations in his personal copy were really just annotations.

Uncle Sam brings the Mafia back to Sicily

The 1943 American invasion of Sicily succeeded in part thanks to mafia aid. The Office of Naval Intelligence recruited Lucky Luciano from prison to keep the New York waterfront functional so supplies would reach U.S. forces in Europe unimpeded. Luciano also set up American intelligence with Sicilian criminal elements, exiles, and power brokers to ensure the invasion was well-received. In doing so, the Americans ended up bringing the Sicilian mafia out of the shadows, where it had been sidelined after Benito Mussolini and Cesare Mori's anti-mafia campaign of the 1920s and '30s.

After the invasion, the OSS (forerunner of the CIA) began consolidating control of Sicily. According to Italian journalist Ezio Costanzo's book "The Mafia and the Allies," however, mafia elements wanted control of their old turfs and rackets. Since they had aided the American invasion and kept Sicily in line, they expected to be rewarded with some of their old control of the island, and the Americans gave it to them.

The Army's Office of Civil Affairs gave the mafiosi local offices and the right to carry firearms. Don Calogero Vizzini became mayor of Villalba, drug trafficker Max Mugnani was put in charge of pharmaceuticals, and another controlled the island's wheat supplies. Officially, they and their underlings were employees of the U.S. Army, who, in return for their service, were allowed to run their criminal activities undisturbed. As for Luciano, Washington sprung him from prison in 1946 for his trouble.

Sicilian Cosa Nostra bombs the pope's basilica

In 1993, car bombs ripped through the offices of the Diocese of Rome near the papal Archbasilica of St. John Lateran. The attack was particularly symbolic, since St. John Lateran is the seat of the pope as bishop of Rome and the old center of the Catholic Church before it shifted to the Vatican.

The bombing was believed to be Cosa Nostra's response to two events. First, Cosa Nostra boss Salvatore Riina was arrested after 20 years on the run. Second, Pope John Paul II visited Sicily and torched the mafia after a handful of officials were murdered for fighting against people like Riina. The pope's support gave anti-mafia crusaders a major jolt, so Cosa Nostra decided the church needed to be intimidated into silence.

The mafia's attack on the church was somewhat unprecedented, especially due to some mafiosi's religious devotion to certain religious figures. For instance, according to an OCCRP report, mobsters across the board love the Virgin Mary, while Bernardo Provenzano was a devotee of St. Padre Pio. Regardless, the intimidation tactics failed, as Pope Francis upped the ante in 2014 by telling mafiosi to get ready to burn in hell if they did not repent.

Anthony Raimondi claims involvement in killing John Paul I

Pope John Paul I's short papacy ended after 33 days, allegedly of a heart attack. In 2020, however, former mafia hitman Anthony Raimondi claimed on the Jordan Harbinger Show that the pope had been murdered to conceal a massive stock fraud his (alleged) cousins, including Vatican Bank head Paul Marcinkus, orchestrated in 1975. The FBI and Italian government were powerless since the Vatican was a sovereign country, and dropped the case.

When John Paul I was elected in 1978, Raimondi said the pontiff planned to expose the fraud and defrock and excommunicate the perpetrators, placing them at the mercy of U.S. and Italian authorities. So Raimondi's cousins called him to rope him into the plot to kill John Paul I -– peacefully. Raimondi would testify to God that the pope was killed humanely.

Marcinkus allegedly killed the pope with potassium cyanide, while Raimondi refused any direct participation. Naturally, the story is nuts and few believe it, but there is one piece of evidence supporting poisoning: John Paul I had darkened fingernails –- a side effect of cyanide. After John Paul II announced his intention to pursue the matter, they threatened to kill him too. "I'm going to hell, easily," Raimondi said. But apparently, the pontiff relented, to Raimondi's relief.