11 Things Police Look For At Crime Scenes

For many people, crime scenes must seem like supremely chaotic settings. Though the details vary, it's rarely a calm or ordered setting. Often, objects are stolen, homes are broken into, and a human being may have lost their life — perhaps with their remains left behind in the middle of all the destruction. Police investigators are typically the ones who have to start the formal process of making sense of it all.

For those investigators, that all starts with a careful examination not just of the overall crime scene, but of minute details. Those can become evidence that, if it is all collected and analyzed carefully, might be able to help solve a case and bring perpetrators to justice. So, while an untrained observer might dismiss an out of place hair or decline to really examine the state of a deceased victim, investigators must pay close attention to many things at a crime scene. Those shoe prints outside? The discarded shell casing on the floor? The fingerprints that took hours of work to recover and identify? All could be vital clues that make the difference between a cold case and a case solved. Here are some of the large and small things police look for at a crime scene.

The first step is scene recognition

The very first thing an investigator will look at when they arrive at the scene is the scene itself. This broad process, often referred to as scene recognition, allows them to take stock and plan how they will move through the space and collect evidence while disturbing as little as possible. This will likely include sketching and measuring the scene to help everyone gain a clearer understanding of the overall space and what may have happened.

The first move is to establish the boundaries. What counts as part of the scene and what doesn't depends on many factors, from the size of a property to the location of a body. Investigators will establish the core of the scene where they expect most of the crime occurred and where they're likely to find the most relevant evidence. Then, they'll block access to a larger area around that core to help keep the scene secure and evidence as pristine as possible. At this point, they'll also have begun planning the path they will take to collect as much evidence as possible with the lowest impact.

With all of that planning hopefully in place, next comes paperwork in the form of contacting a judge, who will then issue a search warrant where necessary. Without a proper search warrant, all of an investigator's hard work to establish and secure the crime scene could go to waste when it's put in front of a defense attorney at trial.

Bodies

If police come across human remains at a crime scene, these will swiftly become the focus of evidence collection. In situations where a body has been around for a long time, a medical examiner or similar professional may need to confirm that the remains are human. After that (or when it's more obvious the remains belonged to a member of our species), investigators then have to consider the state of the body.

There's a lot to look at, too. A body may show obvious or not-so-obvious signs of struggle or death, from wounds to torn clothing to pools of blood. Investigators will also want to consider the positioning of the body, which not only offers vital clues about how that person died, but whether or not they fought off an attacker or were moved during or after their death. Clothing on the remains can also hold clues, such as bunched or torn clothes that might indicate someone moved the individual. Investigators will also look for evidence of anything that's been removed from the body, such as a suspiciously light band of skin on a finger where a ring might have been.

Other marks on clothing or the body itself could also be evidence, whether it's dirt from another location (hinting that the body was moved or the deceased had recently been somewhere else) or fluids that could be from advanced decomposition.

Ballistic evidence

When it comes to gun evidence, investigators may see an obvious gunshot wound on a victim, note discarded shell casings, or even smell the scent of recently fired gunpowder in the air. Even seemingly inconsequential pieces of evidence could solve a case. For example, ballistics experts might be able to match a bullet fragment to the uniquely rifled interior of a particular gun. So, the crime scene will be combed for projectiles, which could be lying in the open or embedded in surfaces such as a wall (where they can illuminate a bullet's trajectory). To preserve evidence, investigators on the scene may remove whole sections of that wall and send it to a lab, where an expert will carefully remove the projectile.

If weapons are found at the scene, investigators will take note of the ammunition caliber or gauge, manufacturer information, and the presence of gunshot residue from a fired weapon. Testing for gunpowder residue left behind on a person's hands can determine if they've fired a weapon recently.

Testing gunpowder residues that are left behind on a victim or other surface can be more definitive, as nailing down the amount of gunpowder there can indicate how close a person or object was to the gun as it was fired. However, for that evidence to be of any use, investigators have to be supremely careful when they collect evidence, lest it get contaminated by anything between the crime scene and the lab.

DNA evidence

Practically every person has a unique genetic code that distinguishes them from the billions of other humans on the planet (apart from identical twins). The chances of two unrelated people of Caucasian descent having the same genetic profile is approximately 1 in 575 trillion (via Nature Reviews Genetics). This all means that DNA can make a very strong case that someone was at a crime scene.

At a crime scene, DNA-minded police investigators will begin by looking for biological material. This includes blood, hair, teeth, bodily fluids, and just about anything else that could come from a human body, living or otherwise. They will also look for objects that could have come in contact with a person and might still hold traces of their DNA, like toothbrushes, cups, clothing, and even material gathered from beneath a person's fingernails. This may be referred to as touch DNA, as it's a small amount of material often left behind by someone literally touching an object or another person. Investigators will have to be extra careful not to contaminate samples before they're sent to a lab for analysis, so precise collection and good record-keeping is just as important here as with any other piece of evidence.

Unless someone's DNA is already in a database — a distinct possibility for a missing person or someone who's already been convicted of a crime — investigators may also take reference samples from people associated with the crime to compare and clear individuals or mark others for further investigation.

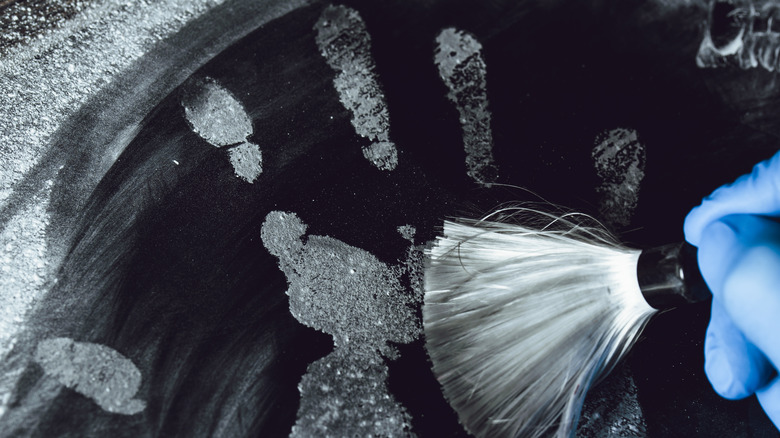

Fingerprints

Finger and palm prints are made when the oils created by a person's skin make contact with a surface or when a person touches soft materials such as wax or clay. If they're visible, those prints are called patent prints. If it takes more work to see them, they're deemed to be latent.

The fine swirls, loops, and arches on prints are highly individual (even identical twins have unique prints), and if compared to prints from the right people, can indicate who was involved. One of the earliest cases that hinged on latent prints took place in 1905, when English shop owner Thomas Farrow and his wife, Ann Farrow, were murdered. A thumbprint on a cash box was recovered, analyzed by Scotland Yard, and linked to Alfred Stratton, who was accused of the murder alongside his brother Albert.

In modern investigations, visible patent prints are usually photographed. Latent prints may be recovered by dusting. However, while this will make them visible, dusting can ruin other evidence, so an investigator may try other methods first. These include using lights such as lasers or LEDs with special filters to more easily view prints. They can also apply fumes of cyanoacrylate — otherwise known as super glue — to a hard surface. The cyanoacrylate bonds to oils and make them more visible. Other chemicals can do much the same on different materials. For example, when ninhydrin is applied to a porous surface with a little steam, it can turn prints a dramatic purple.

Human behavior

Sometimes, investigators need to look for something far more subtle than bullets: human behavior. Research published in a 2022 edition of Forensic Science International: Synergy found that investigators tasked with examining a virtual crime scene were more likely to pick up on important behavioral information if they had psychology training. Training is especially important, as police shouldn't rely on assumptions or misconceptions. As the authors of the study argued, even seasoned investigators can fall prey to these cognitive traps and miss vital clues.

So, what exactly should they be looking for? Few researchers seem to agree. Some have suggested establishing a set of criteria that can help investigators take a regimented look at behavioral cues and patterns, but others argue that this can cause tunnel vision and restrict the mental flexibility necessary to see this form of evidence in the first place.

Criminal profiling at crime scenes may focus on a person's past criminal behavior, personality traits that may push them to commit a crime (like impulsivity or aggression), or underlying mental or behavioral health issues that could do much the same. However, as the authors of a 2021 review published in the International Journal of Law and Psychiatry note, even after decades of practice, there's little concrete evidence that supports the behavioral conclusions often made by criminal profilers. So, while police investigators may try this technique at a crime scene, they should be doing so with an open mind and plenty of caution.

Blood patterns

It's not just the presence of blood at a crime scene that's of interest to investigators, but how that blood landed on a given surface. Often known as bloodstain pattern analysis, this investigative niche can help investigators examine the size, shape, and pattern of blood stains to figure out what was injured by whom, where everyone was, and what weapons were involved. Blood that falls directly into a surface often forms a round mark, for instance, whereas drops or spatters falling at an angle can indicate a weapon's swing. Gunshots often produce many small droplets, while handheld impact weapons tend to form larger drops.

Meanwhile, the overall pattern may help investigators zero in on where an injury was incurred. They may also be able to determine if a victim moved or was moved. Analysts will also often use their geometry skills and even computer programs to write equations, calculate angles, and make their conclusions on bloodstain patterns all the more solid.

A few factors complicate bloodstain analysis. If a person loses a lot of blood, the volume of fluid may overwhelm any patterns that might form. Too little, and investigators only find a small amount that tells them next to nothing. However, if a sample may have valuable information, an investigator will take high-resolution photographs for in-depth study. They may even remove whole sections of material for much the same reason, as well as for DNA sampling (especially useful if multiple victims left blood behind at a scene).

Drug evidence

When investigators arrive at a crime scene, they may often do so with the expectation that drugs are involved. Whether a person was harmed or even killed by drug use, or if the drug trade was connected to a crime, there's a non-zero chance that even newbie investigators will have to look for drug evidence when they get to a scene.

Sometimes, that evidence is obvious, especially when it comes in the form of the drugs themselves or the paraphernalia used to consume them. At other times, investigators will have to do more digging to confirm the presence of drugs, calling on the principles of forensic chemistry to test for drug residues. This technique can also be used to pinpoint the presence of explosives and poisons at a crime scene.

Objects that investigators suspect hold drug residues will be collected and sent to a lab for testing. These can include clothes, bags, food containers, and vehicles that may have been used to transport substances. Anything that may present a hazard to investigators needs to be handled with serious caution, such as hypodermic needles that must be placed in puncture-resistant containers. Meanwhile, the toxic chemicals used to manufacture drugs like methamphetamines present a serious hazard to people who touch or inhale them, so these are usually collected in small amounts and placed in multiple layers of containers to protect investigators and first responders.

Tracks

One of the major reasons first responders and police investigators have to be very mindful when entering a crime scene lies right beneath their feet. That's sometimes literally true, as tracks in and around a crime scene can tell a very interesting story. These tracks frequently take the form of either shoe prints or tracks left by a vehicle's tires in the surrounding terrain. If these impressions are clear and well-documented, police can match these tracks to databases assembled by fellow investigators and manufacturers.

Prints are broadly considered to be one of three types: visible prints made when material on a shoe or tire transfers to another surface (like a bloody shoe print), plastic prints made when a track is pushed into a soft surface (such as mud or clay), and latent prints that are hard to see without the help of powders, lights, or other techniques.

As for actually collecting this form of evidence, high-resolution photographs once again come in handy here. Investigators might also attempt to lift prints or even remove objects containing a print, like a section of carpet or floor tile. For sufficiently stable plastic prints, investigators can try to make casts of the tracks. Properly identified tracks can do a lot to point police toward the truth. A shoe print, for instance, can indicate a brand, model, and particular shoe size (not to mention a person's movements), making up a collection of data that can considerably narrow a suspect list.

Hair and fibers

Though people may not always want to think about it, the truth is that humans shed a lot. Most healthy people will shed somewhere between 50 to 100 hairs every day, meaning we leave behind little mementos nearly everywhere we go. You may think that's too gross to consider for very long, but that is good news for police who come across hairs during a crime scene investigation. The same sort of interest goes for fiber, too, which can transfer from textiles like clothes, furniture, or carpets onto victims, suspects, and objects involved in a crime. Unique fibers that are found at both a crime scene and, say, on a person's clothes or in the trunk of their car may help link a perpetrator to the scene. In the 1982 trial of Wayne Williams, fiber evidence linked him to 12 potential victims. Furthermore, fibers found in his car and on his remains led to two murder convictions.

At the crime scene, police will first identify areas that will give useful samples, such as carpets, clothing, and weapons, and then carefully collect evidence (being extra cautious to avoid cross-contamination). For hair, analysts can tell investigators if the sample is from a human, and whether or not it was dyed, treated, or otherwise came into contact with certain chemicals. As for fibers, they can typically narrow samples down to a certain type (natural, synthetic, or manufactured fibers) and sometimes even a particular product if fibers are unique enough.

Insect activity

While you may hope to keep any number of insects out of your home, they can be quite helpful in many ways, from eating up pests to pollinating flowers and food crops to keeping the soil in your garden nice and healthy. They can also be surprisingly helpful on a crime scene, though investigators may need a strong stomach to take a good look at the bug-related evidence.

That's because the field known as forensic entomology focuses on insect activity in and around human remains. When a person dies, unless their remains are immediately addressed, chances are that decomposition will start, the body will emit gasses, and flesh-consuming insects known as necrophages will smell the gasses and start to arrive en masse. These can include an array of bugs, with flies being one of the most commonly recognized ones.

Those flies and other insects usually lay eggs in those remains. With the help of an entomologist, investigators can determine how old those larvae are, which can then help them narrow in on when a person died and how long their remains have been at the crime scene. It may also clear some, as in the case of Kirstin Blaise Lobato, who was freed in 2018. She had been accused of a 2001 murder and subsequently spent 16 years in prison. A forensic entomologist noted that the lack of insect activity on the body showed that the victim died while Lobato was clearly elsewhere, and her conviction was overturned.