What Would Life Be Like If 9/11 Never Happened?

What if the 9/11 attacks never happened? Pundits have struggled with this question. Although the attacks had relatively little impact on most Americans' daily lives, they radically changed geopolitics and governance, birthing the never-ending Global War on Terror, the TSA and modern airport security, and the curtailing of civil liberties in the name of security. These precedents established after 9/11 are still used today to intrude into Americans' lives.

Without 9/11, would life really be different? Perhaps. One can be forgiven for thinking, given the ubiquity of global terrorism, that things would be the same. But terrorism wasn't new. It just struck so close to home that it became real to Americans. In the absence of 9/11, Americans might have responded differently to elections and attempts to pass the policies the attacks birthed.

No Authorization for Use of Military Force

The aftermath of 9/11 saw the global escalation of American military activity, especially in the Middle East and South Asia. This expansion, which has to date resulted in military actions in at least 14 countries, was possible thanks to the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force. The legislation, also known as Public Law 107-40 or the War Powers Resolution, allowed President George W. Bush to use all necessary and appropriate force against any country, organization, or individual who may have aided and abetted the 9/11 attacks. It passed with near-unanimous bipartisan approval in the Senate and served as a declaration of war against Taliban-ruled Afghanistan for sheltering Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden — the 9/11 mastermind.

The resolution has been criticized as a blank check on presidentially directed foreign military activity. In addition to allowing the pursuit of 9/11-connected individuals, it also allows the president to pursue anyone who might harbor individuals or organizations involved in terror activities against the United States in the future –- even if no hostile activities have occurred yet. In practice, this has meant that presidents from Bush to Joe Biden have been able to justify American-led military activity abroad against groups that had nothing to do with 9/11 (or did not exist) without congressional approval -– something the 1973 War Powers Resolution explicitly banned.

Wall Street might have held out longer

New York City is considered the world's financial capital, but post-9/11, that title more accurately goes to the New York Metro Area, due to the post-9/11 exodus of financial firms from Lower Manhattan's Wall Street. The 9/11 attacks hit financial firms quite hard -– many had offices or even headquarters inside the World Trade Center or near it. According to Fortune, 40% of all deaths were among finance employees –- Cantor Fitzgerald lost nearly 700. Other companies included American Express, Morgan Stanley, and the Bank of New York. After the attacks, many of these companies packed up and left for the surrounding suburbs, particularly New Jersey and Connecticut, or other parts of Manhattan. It was not worth putting all their assets in a single place only where a 9/11-style attack could decimate them again. The Nasdaq exchange, meanwhile, ditched Lower Manhattan for Times Square.

Although the transformation of the Financial District to a more economically diversified, residential neighborhood was already underway, 9/11 accelerated it considerably. After the attacks, NYC officials and developers quickly met to redevelop the area and prevent it from decaying as firms left. The result was a high-end residential shopping district, complete with luxury boutiques, apartment complexes, and eateries. So while pre-9/11 Wall Street usually went quiet after business hours, the destruction of the World Trade Center and financial exodus turned the area into one of the city's hottest commercial and nightlife spots.

No Patriot Act

Following the terrorist attacks, Congress passed the Patriot Act with near-unanimous congressional approval, buoyed by Gallup polling that found a steady increase in support for the law from 2002. Without 9/11, Congress probably would not have risked alienating Americans with the massive expansion of federal surveillance.

The legislation expanded the federal government's ability to surveil and track Americans in the name of fighting terrorism abroad, allowing agents to use warrantless wiretapping and collect internet search histories, credit card histories, bank account information, and even library records without the knowledge of the suspect(s). The Department of Justice argued agencies could more easily identify and charge terror suspects and trace their activities with such records, which would provide proof or probable cause of criminal activity.

Opponents accused the act of violating First Amendment speech protections and Fourth Amendment guarantees against warrantless searches. The DOJ, in a back-and-forth with the ACLU, said critics had nothing to fear because it only targeted terrorists. The ACLU, however, contended the law's language was so vague that it could be used to surveil and harass anyone who ran afoul of the U.S. government –- even individuals reading or purchasing certain books. The ACLU's predictions came true when the FBI demanded patron records from a consortium of Connecticut libraries, although the case went mostly unnoticed in the public eye. Once Edward Snowden revealed the full extent of Patriot Act spying in 2013, support for the act fell.

Warrantless spot checks might not be a thing

After the 2004 Madrid train bombings and fears that something similar would occur in the U.S., urban police departments and the Transport Security Administration (TSA) began random, warrantless bag searches on subways, at sports stadiums, and even of drivers. Under the Fourth Amendment, such searches normally require a warrant and/or probable cause that a crime has been or will be committed. The searches, unsurprisingly, caused problems, most notably when police denied boarding to those who exercised their right to refuse the search. The ACLU and other critics said it did not improve safety, and they had a point — a terrorist could theoretically refuse the search, go to a different station on the same line, and carry out an attack there. Meanwhile, law-abiding citizens had their commutes thrown off.

The New York City spot-check program went to court in the case McWade v. Kelly. Judge Richard Berman ruled that preventing terror attacks on American trains overrode constitutional concerns because the searches were not intrusive. As noted in the Drake Law Review, however, it is unlikely Americans would have ever accepted these searches without 9/11. Opponents argued the courts were redefining the strict constitutional parameters against warrantless searches by exploiting the fear 9/11 generated. Other courts that heard separate challenges sided with critics, noting that the increased security, touted as a measure to protect Americans' liberty, was actually destroying it.

Flying would be much easier

While the glamorous days of jetsetting and Pan Am were long-gone before 9/11, flying was still tolerable. The response to the attacks, however, turned it into a nightmare with the gauntlet of modern airport security. Before 9/11, passengers could go to the gate without a boarding pass or ID, keep their shoes and coats on, and generally security was a simple pass through a metal detector. As Jeff Price, an aviation security expert at Metropolitan State University of Denver, noted to NPR, "Before 9/11, security was almost invisible, and it was really designed to be that way."

That all changed when President George W. Bush signed the 2001 Aviation Security and Transportation Act, which created the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and introduced new anti-terror measures on travelers. A battery of security procedures followed. Travelers had to remove outerwear and shoes, assent to pat-downs and body scans, and deal with far longer security lines and wait times.

It is unclear whether the agency is actually effective in preventing terror attacks — 9/11 style or otherwise. ABC News learned exclusively from the Department of Homeland Security in 2015 that TSA agents missed objects like fake explosives and weapons up to 95% of the time -– even a fake explosive strapped to a DHS agent's back.

Cockpits might still be open

Along with changes to airport security, the Bush administration and Congress introduced a battery of new rules for pilots and cabin crew. Because 9/11 was deemed a hijacking in which terrorists broke into the cockpits and took control of the airplanes, these new measures were meant to turn commercial airline cockpits into mini-fortresses safe from unauthorized access.

With the Aviation Transportation Security Act, airlines were required to reinforce cockpit doors so they could not be easily broken down. In most cases, this has meant bullet-proof, steel-reinforced doors that only the pilot or co-pilot can open from the inside. The 2002 Arming Pilots Against Terrorism Act further bolstered onboard security by allowing pilots to carry guns in case the cockpit was stormed. Cockpits effectively became no-go zones, meaning passengers (especially children) could no longer visit them in flight and see pilots in action.

While the cockpit restrictions seemed like common sense, they created the possibility of a nightmare scenario if the pilots were incapacitated -– or worse, had malicious intent. The concerns were validated in the 2015 Germanwings tragedy, wherein co-pilot Andreas Lubitz intentionally crashed his airliner, killing himself and all 149 on board. The pilot was unable to stop him because he could not break down the reinforced door Lubitz had locked from the inside. Even the emergency override systems in place allow the pilot inside the cockpit to lock the door, thus preventing the override system from working — which is also what happened in the case of the Germanwings flight.

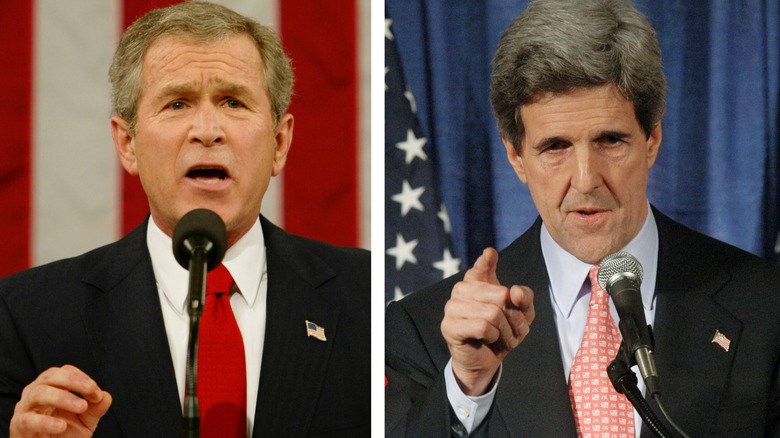

The 2004 election would not have been a national security referendum

The 2004 election, which pitted Democrat John Kerry against Republican incumbent George W. Bush, was a referendum on Bush's response to the 9/11 attacks. Pre-election Gallup polling certainly supported this view, with 49% of Americans ranking terrorism and national security as their chief concerns.

Without 9/11, the 2004 election would have looked very different. The New York Times' Thomas Friedman, French philosopher Bernard Henri-Levy, and Frank Rich (via NY Magazine) all believed Bush would have lost without the ability to present himself as the tough-on-terror president. Kerry would have agreed, as he blamed 9/11 for his defeat. Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, however, noted that without 9/11, Kerry might not even have been the nominee. Democrats picked him to leverage his war service and foreign policy credentials with voters in the aftermath of wars that resulted from 9/11 — like Iraq.

In the absence of the Global War on Terror, the data suggests 2004 would have pitted Bush in a rematch against Al Gore, or another against another Democrat in a campaign centered around the economy and jobs –- top-rated issues for 57% of post-9/11 Democrats and important to 45% of GOP voters as well.

Businesses might not face extra regulations

After 9/11, the FBI concluded the hijackers had managed to fund the attacks using American bank accounts opened without social security numbers and any problems. Their cash transfers, withdrawals, and debit card transactions went unnoticed too. In response to this revelation, businesses and financial institutions were hit with new regulations.

The first set of restrictions came with the Patriot Act, which required businesses to monitor suspicious activities and report them to the federal government. Banks were even expected to flag and close suspicious accounts, sometimes without notification or explanation to account holders. In some instances, banks allegedly targeted customers due to their ethnic or religious background, even without suspicious activity or criminal history. Banks that did not comply could be penalized. All businesses — even car dealerships — were also forced to ramp up background checks on potential customers. For smaller institutions, this meant extra time and employees to conduct the checks, translating into higher operating costs and business closures.

The 9/11 attacks also introduced the regular use of background checks in hiring. According to data from the security company Verified First, only about half of employers bothered to run background checks on potential hires before 9/11. Thanks to employers being more careful with new hires after the attacks, that number is now 95%.

The no-fly list might be a lot smaller

Before 9/11, according to the Immigration and Human Rights Law Review, there were a grand total of 12 people on Washington's dreaded no-fly list. By 2011, it had exploded to 420,000, thanks to the National Terrorist Screening Center database allowing federal agencies to add individuals based on terror suspicions –- not just convictions.

Landing on the list prohibits individuals from flying within U.S. airspace. This is fine for convicted terrorists but causes life-altering problems for those who are unjustly listed. The Ninth Circuit Court has recognized freedom of movement by all legal means as part of the Constitution's guarantee of liberty, meaning that listees with no criminal history lose their rights without due process. Listees have also faced denial of employment and issues with law enforcement on otherwise routine matters.

The list came under scrutiny amid allegations the FBI blacklisted American Muslims to coerce them into becoming informants, but it was not until The Intercept's 2014 investigation that the full picture went public. The criteria for listing people was kept secret for a reason –- they were a gross violation of the American legal standard of "innocent until proven guilty." People have been arbitrarily designated as terrorists without reason or evidence -– sometimes even for social media posts made by others and engaging in constitutionally protected activities, often, without even knowing they were listed. In a final twist, the proof falls on listees to prove their innocence.

Iraq would have been a harder sell

American neoconservatives, including Iraq War architects Douglas Feith and Richard Perle, had been pushing regime change in Iraq since at least 1996. Given the influence such men held with the Bush administration, invading Iraq would likely have been a key Bush priority, 9/11 notwithstanding. But 9/11 certainly made the war an easier sell.

President George W. Bush's case for war alleged Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein had links to Al-Qaeda and was producing weapons of mass destruction. The 9/11 Commission report linked Iraq with 9/11 hijacker Mohammed Atta as a state sponsor of terror. The message was clear: Saddam made America less safe. According to Gallup polling through 1999 (via the Chicago Center for Global Affairs), 74% of Americans supported military action against Iraq. By February 2001, however, another Gallup poll found this number had dropped to 52%.

Immediately after 9/11, support for war spiked to 74% and remained in the high 50s and low 60s, suggesting the Bush administration would have otherwise struggled to convince Americans that Operation Iraqi Freedom was worthwhile –- especially before an election year (OIF began in 2003). In a tight election, going to war with only 52% support -– support that would evaporate if the conflict went badly –- was political suicide. The attacks, however, allowed Bush to invade Iraq without torpedoing his reelection chances in 2004, where he carried the day thanks to concerns about terrorism.

The FBI might not be at your local church or mosque

The FBI came under fire in 2023 for spying on Traditionalist Catholics on the grounds of fighting potential terrorism and violent domestic extremism. Despite the outrage, the practice was not new. Muslims faced the same FBI spying and entrapment schemes in mosques after 9/11. Without 9/11, the spying would probably have been considered intolerable. After 9/11, however, people probably tolerated it because the targets were Muslims, like the 9/11 hijackers. But it set the precedent for spying on everyone else in the name of security.

In one particularly egregious case, the FBI planted an informant in a California mosque in the mid-2000s. He collected congregants' personal information, recorded individuals who had not been charged or suspected of a crime, and passed intel to the bureau. He also attempted to entrap a handful of congregants into terror plots, despite FBI assurances the bureau was building bridges between Muslims and law enforcement. Imam Yassir Fazaga sued the FBI on First Amendment grounds, arguing the bureau targeted his congregants for practicing their religion.

The FBI motioned to dismiss, arguing that the lawsuit would reveal state secrets, and won in district court. Following an appeal and a Supreme Court ruling in the FBI's favor that opened the path to dismissal on the state secrets privilege, the case is in the Ninth circuit, almost two decades after the spying occurred.

There would be no Patriot Day

Following 9/11, a congressional joint resolution and President George W. Bush designated September 11 as Patriot Day in commemoration of the attacks. Patriot Day is not a federal holiday. Schools and offices are not closed. Instead, it is more of a day for Americans to reflect, remember, and honor those who died. This starts with all flags being lowered to half-mast at 8:46 a.m. EST, when the first tower was struck, followed by a moment of silence for the dead.

In 2009, President Barack Obama renamed the day "Patriot Day and National Day of Service and Remembrance" through presidential proclamation. He urged Americans to use the day not just to mourn but also to go out and live as patriots — not just waving the flag but going out and living the values that made America great and got it through the time following the attacks. Most frequently, this is through volunteer work and lifting up one's fellow citizens in a show of unity that transcends other social divisions such as race and religion. A handful of states, including Michigan and Florida, have followed the federal lead and designated it as a state holiday.

Patriot Day is a separate holiday from Patriots' Day, which marks the beginning of the American Revolution in 1775 with the battles of Lexington and Concord.