The Untold Truth Of The Iconic Pan Am Airways

On December 4th, 1991, a giant fell from the sky. Pan Am Airways, the unofficial U.S. flag carrier and, according to Business Insider, the most glamorous, had failed to restructure and would cease operations. For many, it was a shock to see the airline that had pioneered modern aviation disappear, but the collapse had been at least a decade in the making. Political and economic shocks had taken their toll on the airline that prided itself on offering the absolute best service money could buy at 35,000 feet.

Although Pan Am is gone, it left behind a legacy that aviation enthusiasts nostalgically look upon as a time when flying was something more than a simple trip. From the luxurious flying boats of the 1930s to the gourmet meals of the Boeing 747, Pan Am made its passengers feel like they were someone. Here is the untold truth of one of the greatest airlines that ever was.

Pan Am nearly flopped before it started

According to the Pan Am Historical Foundation, Pan Am Airways was the brainchild of four U.S. military officers. By 1927, the nascent airline had won a contract to fly U.S. mail between Miami, Florida and Havana, Cuba. There was just one problem. Pan Am was for all intents and purposes, a shell company with no assets, planes, money, or landing rights in Cuba. If Pan Am could not complete its first mail delivery, which it still was incapable of doing one week before the deadline, the United States Postal Service could revoke the contract.

Pan Am's competitor Juan Trippe (second from right, above), a former airline executive, had secured landing rights in Cuba and a plane to deliver mail, but he did not have a contract. So he negotiated with Pan Am and a third group called Florida Airways to create "Atlantic, Gulf, and Caribbean Airways." Thus, according to the U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission, Pan Am Airways became a subsidiary of the new corporation with Trippe as president. Trippe's government connections ensured that Pan Am had no competition, allowing the new airline to focus on flying its customers to Latin American beach paradises in style. It did not disappoint.

It got its commercial start thanks to Prohibition

Although Pan Am had originally restricted itself to mail and cargo, the airline soon saw an opportunity to break into the growing commercial air market. According to "Empire of the Air," not only did the wealthy desire to travel, but they also wished to drink. The United States had passed Prohibition in 1920, which according to Britannica, did not ban alcohol, but forbade the sale, manufacture, or importation of it.

For wealthy Americans, going abroad was an easy way to skirt the restrictions, and Pan Am was there to help. According to "Empire of the Air," passengers could fly to Cuba from Miami and drink on the beach to their hearts' content for $100 (~$1,600 today). Airline president Juan Trippe spared no expenses to sell the airline's benefits. According to Business Insider, Trippe struck a joint advertising deal with the Cuban Bacardi Rum, inviting Americans to drink and enjoy their "rum in the sun." Because of its links with Bacardi, Pan Am became known as the "cocktail circuit," a reputation it would enjoy for much of its existence as the provider of the best airline service bar none.

Its clippers made the first Transpacific crossing in 1936

Pan Am quickly expanded its operations to cover the Americas. According to "Empire of the Air," the airline went from 118 employees and 9,500 passengers in 1928 to 2,700 employees and nearly 107,000 passengers by 1934. By 1936, the airline was ready to expand into the transpacific market to take tourists to Asia. Those able to afford the tickets got to experience the Clipper, a luxurious flying boat that could land anywhere on water.

Pan Am's Clipper fleet of flying boats is less-known outside of aviation circles, but it was the peak of luxury in the 1930s. Business Insider notes that Pan Am flew to Latin America and Caribbean countries that did not have the facilities and runways to receive landing aircraft. The Clipper, however, could land in their ports, opening the Pacific to American air tourism.

According to the National Air and Space Museum, the Pan Am route to Asia was trailblazing. Flying From San Francisco to Honolulu involved crossing over the ocean with no airport for an emergency landing. Nevertheless, the Hawai'i Clipper left San Francisco's port with seven passengers, including Standard Oil executive Richard Bradley, whose logbook records the 10-day flight. Each passenger paid $799 (~$14,000 today) for this experience, which Bradley described pleasantly for the beautiful views of the Pacific Islands and excellent service on the plane. One of Bradley's fellow passengers was Fred Noonan, who made the headlines in 1937 alongside another famous aviator –- Amelia Earhart.

Fred Noonan worked for Pan Am

Amelia "the Lady Lindy" Earhart became famous as the first woman to fly across the Atlantic from Newfoundland to Northern Ireland. According to PBS, Earhart soon eyed a greater prize – the circumnavigation of the globe "as near its waistline as could be." Accompanying her was navigator Fred Noonan, who according to Fox, had served as navigator for Pan Am's transpacific Clipper fleet. Before GPS, navigation relied on the stars and other celestial bodies, so Noonan's 20 years of expertise were invaluable to Earhart's ambition.

Earhart, Noonan, and two others attempted their first circumnavigation of the globe beginning from Oakland, California. The team made it to Honolulu but had to call off the endeavor after technical problems grounded their plane. The determined Earhart made a second attempt in 1937 from Miami eastward, this time just with Noonan.

Earhart and Noonan, per History, made it all the way to New Guinea, an incredible feat for the time. But unfortunately, as they approached the U.S. territory of Howland Island, Earhart failed to sight the island. The coast guard on the ground tried signaling but lost contact. Earhart presumably attempted a water landing but was never seen again. Two brilliant aviation careers ended that day, and the pair's disappearance is still an unsolved mystery, as neither their plane nor their bodies were ever definitively found.

Charles Lindbergh was a board member

Charles Lindbergh, according to History, found fame as the first man to complete a transatlantic flight from New York to Paris solo in his plane "The Spirit of St. Louis" in 1927. Lindbergh involved himself in business ventures thereafter. According to former Pan Am pilot Ed Spellacy (via the Pan Am Historical Foundation), the U.S. government refused his services because of his research collaboration with the German Luftwaffe, despite offers to bring German jet engine technology to America. So he went to Pan Am president Juan Trippe, with whom he had worked before, and asked for a job there.

Trippe, for unknown reasons, rejected Lindbergh's job request and refused to hire him to a board position until after the war was over. Then, Lindbergh finally got a coveted Pan Am board position and was an advisor to the president. Despite his wealth, fame, and position within the company, Lindbergh always flew economy incognito. He did, however, use his rank to visit cockpits and chat with the pilots. In one amusing incident, a flight attendant called him "some nut downstairs" claiming to be Charles Lindbergh. But when he showed his ID, the embarrassed flight attendant let him in.

Spellacy recalled Lindbergh as a humble man and "a delight in the cockpit." He traded stories and discussed routes and mechanical issues with the pilots when not in his seat. "In short, he was a really nice guy."

The food was great

Airline food today is generally terrible. The Atlantic even ran a piece noting the general consensus of disgust at airline food. But Pan Am was different. Its cabin service included gourmet food for all passengers, from economy to first class. Professor Elizabeth Zanoni's research (via Culinary Historians of NY) has confirmed what many have seen in pictures or heard from older relatives: Aircraft dining from the 1940s-1970s was quite the experience. First class passengers were served multi-course meals (including caviar and steak) with real silverware, glasses, and china, paired with cocktails and expensive wines. Meat was cut and served in the aisle, having been cooked either in the airport kitchen or in the aircraft itself.

The nostalgia site Everything Pan Am hosts a number of menus that attest to the food's quality. A 1940 Clipper flight to Jamaica (first class only) offered chicken broiled and served with wine sauce and Del Monico potatoes, or chicken a la Reine from Jamaica's famous Myrtle Bank hotel. A '50s first class menu offered beef bourgeois, two wines, four cocktails, and dessert liqueurs. Economy passengers, according to former stewardess Laurie Wilfert (via Glamour) also had personalized meal service. One example included a four-course meal of veal, cream of tomato soup, salad, and dessert. Wine was available for an extra charge. But it came at a price. As Vox notes, flying back then was much more expensive.

Pan Am pioneered the rewards programs

Pan Am was known for pampering its first class customers, but it extended similar benefits to its business passengers too. According to Jennifer Coutts-Clay, Pan Am's former general manager of product design and development (via Travel and Leisure Magazine), the airline developed a business class frequent flier program called the "Clipper Class," named after the iconic flying boats of the 1930s. But it was not a mileage program as many are today. Instead, frequent fliers paid $1,000 per year (~$3,000 today) for personalized vacation packages, hotel accommodations, and most importantly, a global travel service that Pan Am passengers could use in case of an emergency. In the pre-internet age, this last service would have been invaluable, since even small mishaps could ruin a vacation.

The Clipper Class had another feature that made Pan Am special at the time. Members had a direct say in the running and management of the airline. Members were invited to social events with airline executives, sat on Pan Am's business and development committees, and gave direct input to Pan Am's marketing executives to improve the airline. Although Clay-Coutts notes that airlines preserve these practices in some form, Pan Am's status as the world's premier airline made membership in the Clipper Class something more. It meant you were "somebody."

It had a 'Fearful Fliers' program

According to the BBC, fear of flying (aka "aerophobia") is classified as a medical condition characterized by a crippling fear of airplanes that may affect as much as one-third of the U.S. population. Pan Am figured that if it could help aerophobes overcome their fears, they would surely patronize the airline that had opened to them the world of flight.

According to Carol Lawson, writing in the NY Times in 1978, the "Fearful Flyers" program was the brainchild of Pan Am pilot Truman Cummings. His 2-week course charged $100 dollars/person to overcome their fear of flying. Lawson described the program as a combination of group therapy and religious revival. Participants confronted their fears rather than dulling them with alcohol or drugs, took part in deep breathing exercises, and engaged in positive thinking. As Cummings said, the "procedures [were] corny, evangelistic or whatever—but they [worked]."

Lawson's story backs Cumming's assertions, at least for her group. On the short Pan Am-sponsored "graduation flight" from New York to Atlantic City, Cummings kept the cockpit door open and allowed passengers to enter and observe him, giving them a sense of security. It worked. The passengers, although tense on the initial flight, relaxed and enjoyed the return. Lawson, although she still did not like flying, no longer found it a terror.

Pan Am had legendary flight attendants

One of the keys to Pan Am's success was the airline's legendary flight crew, especially its stewardesses (as they were known at the time). According to You Magazine, Pan Am stewardesses were recruited from educated, ambitious women with a zest for adventure. Applicants had to speak at least one foreign language and have a college degree, "symmetrical features, clear skin, height between five foot three inches and five foot nine, and be trim." There were girdle checks and "weigh-ins" at regular intervals.

Despite the requirements, former stewardesses Laurie Wilfert (via Glamour), recalled her days fondly. From the Italian-designed iconic blue uniform, to "being treated like royalty," it seems that life really was that great for the 3-5% of women that made the final cut. Former stewardess Susan Davis (via CBS) described it as a "sorority" she hadn't realized she needed. Pan Am flight attendants regularly enjoyed high pay and ample vacation time during layovers around the world.

Because of their reputation, Pan Am stewardesses were often the objects of male passengers' attention. According to former stewardesses interviewed in the documentary "Come Fly with Me," men often took off their wedding rings when trying to pick them up. The stewardesses even had a name for the most insistent –- "stewbums."

Pilots were so respected that a conman impersonated one

Steven Spielberg's "Catch Me If You Can" tells the life of Frank Abagnale, Jr. (above), who lived a life of crime writing bad checks. Among his stunts was the impersonation of a Pan Am pilot. According to "Come Fly with Me," Pan Am pilots were akin to celebrities, the male counterparts to the blue-clad stewardesses. Abagnale, at least according to his interview in "Come Fly with Me," saw a Pan Am flight crew outside the Commodore Hotel in NYC and claimed to have been "so impressed" with them (and probably smitten, too) that he decided he wanted that life as well. So he successfully impersonated a pilot for two years, somehow obtaining a uniform and an ID card.

Abagnale claimed that the Pan Am uniform allowed him to cash bad checks. Since Pan Am pilots had "that kind of status," the tellers paid attention to him, not the bad check. Without the uniform, he would have been "laughed out of the bank" for such a clearly-fake check. Abagnale was able to travel for free as a Pan Am employee as a "deadhead." Sometimes, however, the pilots would offer him the plane controls. Not knowing how to fly it, according to History Collection, he put the plane on autopilot.

Seem too good to be true? According to Esquire, the story itself is Abagnale's biggest con of all.

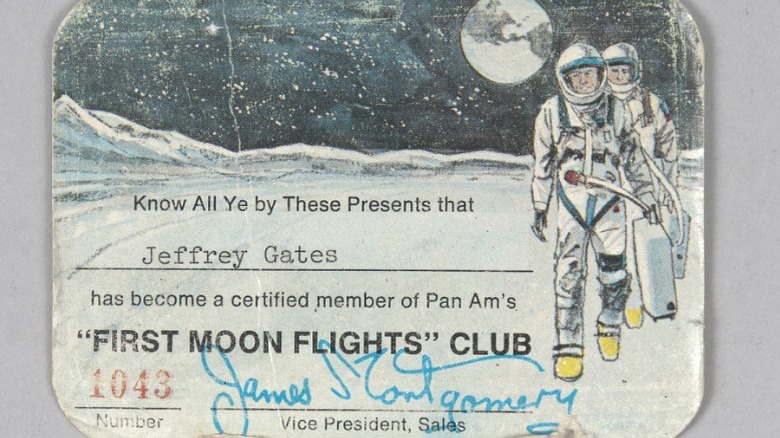

Pan Am offered space flights ... sort of

According to the Air and Space Museum, an Austrian travel agency allegedly requested a Pan Am ticket to the moon for one of its customers. The documentary "Come Fly with Me" gives a different story, attributing the idea to a couple of drunk employees who were working on Christmas. Regardless, the airline created a list of people interested in commercial space travel and sent them "tickets to the moon" for an amount that "was not fully resolved," but probably would be "out of this world." The "tickets" consisted of a small membership card for the "First Moon Flights Club," which counted President Ronald Reagan, journalist Walter Cronkite, and, according to former Pan Am communications VP Jeff Kreindler, a man that wanted a one-way ticket to get rid of his ex-wife.

At first, the whole thing seemed like a publicity stunt. But as Stanley Kubrick's 1968 film "2001: A Space Odyssey" showed, if anyone could pull it off it was Pan Am. Although it stopped accepting new club members in 1971, the airline promised until its dying day that it would redeem the vouchers for actual space tickets. Unfortunately, the management did not count on a series of political and financial disasters that would be its death knell.

Pan Am did not fly domestic in the lower 48

For all its reputation and fame, Pan Am never flew domestically outside of Alaska and Hawai'i. Its luxurious brand only worked for long-haul international flights. According to the World Airline Historical Society, the airline had wanted to break into the domestic travel market in the lower 48, but Pan Am faced a major obstacle in the U.S. government and the Civil Aeronautics Board. According to Business Insider, Pan Am's dominance of international travel was primarily a result of the CAD giving the airline the lion's share of the routes. But fearing that Pan Am would monopolize all U.S. air travel, the CAD barred the airline from the domestic market.

As the Journal of Commerce notes, under regulation, this arrangement suited Pan Am. A lack of international airports in the U.S. interior allowed domestic airlines to provide Pan Am's international network with a steady stream of customers. But once the CAD began granting international routes from places such as Dallas to lower-cost competitors such as Delta, Continental, and American Airlines, Pan Am faced unexpected competition. The CAD forbade Pan Am from operating at these new international terminals, necessitating a domestic network to funnel passengers into its JFK and San Francisco hubs, without relying on other airlines. But Pan Am's chances were dashed when an unexpected political crisis hit in 1973.

The 747 and the 1973 Oil Crisis started Pan Am's decline

According to the World Airline Historical Society, Pan Am experienced its golden years in the 1960s, when affordable jet travel opened international tourism to America's middle class. Large jetliners such as the Boeing 747 allowed larger numbers of passengers. Juan Trippe, Pan Am president and founder, ordered 25 before they had even been built. These state-of-the-art aircraft, according to the Pan Am Historical Foundation, introduced a slew of new technologies, a separate upper deck for first class, and four engines.

The 747's 1969 debut was underwhelming. The new aircraft's operating costs eclipsed its profitability because Pan Am had purchased them expecting international air travel to grow at the unrealistic rate of 15% per year. Instead, it collapsed as fuel prices shot up in light of the 1973 Oil Crisis.

According to the NY Times, Pan Am's fleet of long-haul aircraft was dependent on large quantities of Arab oil. So when the price of oil increased, ticket prices increased. In response, Americans traveled less internationally. Since Pan Am had no domestic network to compensate, the airline posted massive losses, exacerbated by increased competition. The Civil Aeronautics Board had been awarding other American airlines increasing numbers of international routes that Pan Am had originally dominated. The competition increased steadily until the industry's total deregulation in 1978.

Deregulation and Lockerbie

During the area of airline regulation, the Civil Aeronautics Board had allowed Pan Am to fly internationally with little competition. But in 1978, Congress passed and President Jimmy Carter signed the Airline Deregulation Act. The federal government no longer fixed airline fares or restricted route access, whether domestic or international.

Deregulation allowed Pan Am to enter the domestic market. According to the Airways Magazine, the airline purchased low-cost carrier National to feed Pan Am's international flights. But the merger was rife with problems. National had operated on much lower costs, including lower salaries. So Pan Am had to raise them even though National's relatively low profits did not justify it. And National's domestic network was too small to feed Pan Am. According to The NY Times, Pan Am's international flights had to be consistently 70% full to turn any profit. If the domestic network did not provide the passengers, Pan Am was not profitable.

In the end, Pan Am overpaid for nothing. Faced with millions in quarterly operating losses, the airline sold the assets that had made it successful -– its prized Pacific routes along with its iconic Park Avenue headquarters. Once the Lockerbie Bombing of Fight 103 occurred, that was it. Pan Am's image never recovered. According to Aviation Law (via Kreindler LLP) and Business Insider, the airline faced a $500 million lawsuit for negligence and was losing $3 million a day. Pan Am folded in 1991. The last vestiges of the Golden Age of Aviation were over.