People Who Died On The Titanic (But Could Have Changed The World)

Nothing in life is a given, and many of us are happy just sort of wandering through, day after day, in an ignorant haze. Tomorrow is going to be there, because it always has been before, and why should anything change? But fortunately, the world is also filled with people who aren't content, who try to make every day the day that they change the world. When something like the sinking of the Titanic takes hundreds of lives in a heartbeat, it changes the world, too, by taking those that could have really, really made a difference.

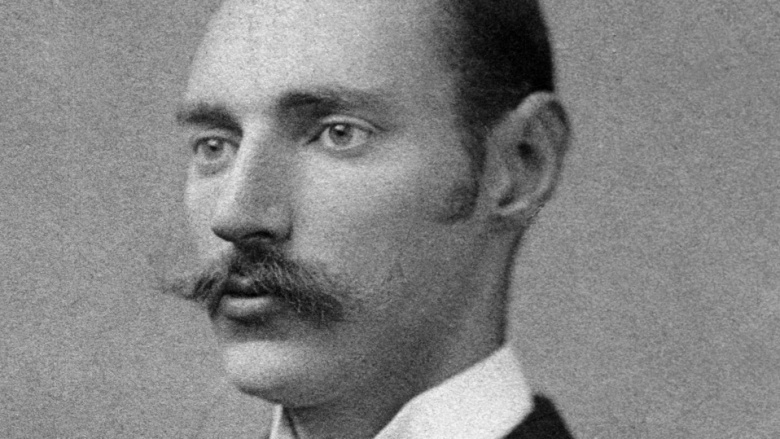

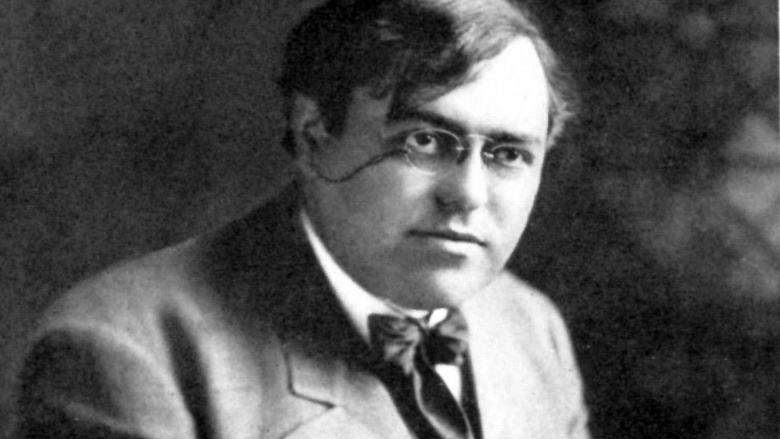

Major Archibald Butt

You know you've made something of your life when the president of the United States not only gives your eulogy but describes you as a younger brother. President William Howard Taft wrote that once he heard about the Titanic disaster, he knew that his old friend had been lost, because there was no way he would have done anything other than remain on deck and help others around him. "... he would feel himself charged, with responsibility for rescue of others," he wrote.

Maj. Archibald Butt wasn't just one of Taft's military aides — he served as the personal aide to President Theodore Roosevelt, too. When Taft and Roosevelt came to proper and presidential blows over policy disagreements, Butt was caught in the middle of their squabbling. It was in the midst of this uneasy political climate that Butt, who undoubtedly had enough of both of them, not only refused to pick a side but decided that this was the perfect time for a vacation to Europe. At Taft's urging, Butt set off on an indefinite vacation and, also at Taft's urging, scheduled some slow, seafaring voyages in hopes that the calm ocean waves and brisk sea air would help him feel a bit more like himself.

The vacation was supposed to last six weeks, but because Butt was more dedicated to his job than most are, he agreed to pay a diplomatic visit to the Vatican and Pope Pius X, while supposedly not working. No one knows just what the visit was for, but the Pope did give him a letter to give to the president on his return.

Butt was on the last leg of his journey when he set off on the ill-fated Titanic — according to one witness, he was last seen in the smoking room with Francis Millet. That was after he had helped get passengers into the lifeboats, and another remembered overhearing him tell one man that "women will be attended to first, or I'll break every ... bone in your body." The pope's letter to the president was never recovered, and neither were Butt's remains.

Benjamin Guggenheim

Yep, he was one of those Guggenheims. Today, the name is more closely associated with art than with their original endeavors, such as mining. Meyer Guggenheim, a Swiss immigrant who first bought two Colorado copper mines in the 1880s, built a mining empire from the ground up and passed it on to his sons. One of those sons, Benjamin, was working full time in the family business by the time he was 20, and he later helped develop and found the International Steam Pump Company.

He died on Titanic only a few years later, and his story is a terrifyingly arbitrary fluke of fate. Originally scheduled to return to the U.S. on the Lusitania (via the New York Times), he was first given the option to take Lusitania's replacement ship, the Carmania, when his original ride went in for repairs. Instead, he opted to be a part of history and take Titanic's maiden voyage. Guggenheim certainly became a part of history, though absolutely not in the way that he intended. He was immortalized as part of Titanic legend, when he and his valet dressed in their finest and declared they were spending their final hours as they had lived — like gentlemen.

One of his daughters, Peggy Guggenheim, became the driving force behind Venice's Guggenheim art museum. As for Benjamin himself, who knows what other contributions he would have made not only to the mining industry but to the charitable causes his family was so well-known for embracing. As it was, his will specified that $115,000 was to be given to charity (while the rest went to his immediate family). In today's money? That's around $3 million.

Daniel Warner Marvin

Daniel Warner Marvin was only 18 years old when he died onboard Titanic. Young, for sure, but old enough that he already had set his sights on becoming an engineer and contributing to his family's film legacy.

The Marvin family didn't work in front of the camera but behind it. His father was the co-founder of the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company and, according to various sources, Marvin was on his way to becoming an engineer in his own right, following in his father's footsteps. The Marvin family not only threw down with Thomas Edison over camera patents but developed an entirely different camera to get around patent restrictions and open up the film industry. Countless early filmmakers partnered with the company to get their movies made, and Marvin's (re-staged) wedding was among the first to be filmed (though that precedent the world could have done without).

He and his young bride were returning to the states after a three-week honeymoon when Titanic sank. After carrying his pregnant wife to the lifeboats, he told her, "It's alright, little girl. You go. I'll stay." His daughter was born a few months later, and his widow destroyed almost all the footage of their wedding. His family's company? They're still going, now known as Biograph.

John Jacob Astor IV

John Jacob Astor IV was the scandalous and controversial heir to the Astor family, and if the only thing you're really familiar with is his building of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, that's a shame. His great-grandfather (and namesake) established the first monopoly in America after first coming to the country carrying only a few flutes (handmade by his brother) and $25. From heading out into North America's unexplored frontier to securing furs for his blossoming empire, he became one of the country's biggest names and richest men? Not a bad deal.

The elder Astor built on his fortune by investing in New York real estate, and that's where John Jacob Astor IV comes in. Not only was he responsible for part of the Waldorf-Astoria (and several other landmark hotels in the area), he was a pretty brilliant jack-of-all-trades. He wrote science fiction novels, invented things like wind turbine engines and, at the time of his death, was the richest man in the world. Just how much he was worth is tough to pin down, but one estimate suggests that he had the equivalent of $58.7 billion in today's money.

The scandalous and controversial part happened when Astor IV divorced his first wife and married another woman, who was a year younger than his own son. They were in the midst of the fallout from that particular media outrage when they decided to head to Europe for some rest and relaxation — unfortunately, they chose to return home on Titanic. The Astors were among those that didn't take the crash seriously at first, hanging out in the gym, chatting, and even cutting open an "extra" life preserver to see what was inside.

His young wife, Madeleine, survived to give birth to their son (and named him John Jacob), while Astor's body was recovered on April 22 and buried in New York.

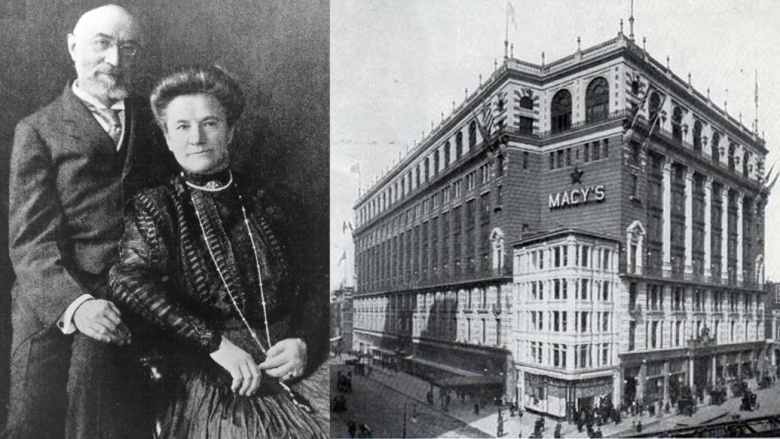

Isidor and Ida Straus

Every so often, you read about someone who makes you believe in the better things in life again, like true love, decency, and self-sacrifice. That's exactly what the story of Isidor and Ida Straus is filled with. The couple wasn't just incredibly wealthy — they were major charitable donors who gave away a huge amount of their fortune to causes across their adopted city of New York.

Perhaps it's because they remembered what it was like to have nothing — after crossing the Atlantic from Germany, they settled in Georgia and, with Confederate currency becoming worthless by the end of the Civil War, they went bankrupt. The Strauses insisted on settling all their outstanding debts before moving to New York (something that few people bothered doing). There, Isidor found work with R.H. Macy & Co., eventually becoming a congressman, as well as company owner. Even as he walked through the massive department store that he owned, oversaw, and ran, staff remembered him as someone who not only knew everyone's name but felt responsible for their well-being and took an interest in their lives and the lives of their families. Straus and his partners set up the first Mutual Aid Society for employees, made sure they were given a hot meal every day, and that they had life and burial insurance. Sounds bizarre in today's world, doesn't it?

In turn, they had dedicated employees who were moved to tears with the news of their deaths on the Titanic. Even though Ida famously had a place in the lifeboats, she refused to leave her husband and chose to die at his side. She gave her place and her coat to her maid. While Ida's body was never recovered, Isidor's body was, and he was buried amid tributes and mourning that moved the whole city.

Henry Forbes Julian

Sifting through the details of the life of Henry Forbes Julian is like reading a textbook written by someone way, way smarter than you could ever hope to be.

The Irish-born, English-educated metallurgist was also an African explorer, who was one of a handful of European men to first see Victoria Falls (and, undoubtedly, countless other sights throughout the heart of Africa). He traveled extensively through Mexico and Europe too, documenting archaeological artifacts and previously unexplored territory, all while doing what he went there to do — pioneering new techniques in metallurgy and mining. While working as an engineer and consultant on mines in Africa, he was also writing ground-breaking treatises and applying for patents.

During his travels, he'd made the trip across the Atlantic at least 13 times. By the time he got on the Titanic, the crossing was fairly everyday for him and, according to a message to his sister-in-law, he wasn't all that blown away by the added amenities on Titanic. In letters to his wife (who had decided to stay behind), he spoke of Titanic's luxuries in rather glowing terms (apparently, a cabin that was basically a bedroom had won him over) and also told her that he had already known a good number of the staff from his previous trips across the Atlantic. His body was never found.

Quigg Edmond Baxter

The unlikely named Quigg Edmond Baxter spent his post-school years playing football and then hockey for the Montreal Shamrocks Hockey Club. Hockey being what hockey is, he only lasted a single season before getting hit in the face with a stick so hard, he lost half his eyesight. Hockey players being as badass as hockey players are, he started coaching and playing amateur hockey in Europe instead of retiring like a sane person. Baxter ended up being one of the driving forces behind organizing the first international hockey tournament in Paris and was on his way back home when he boarded the Titanic.

As he was perhaps the most typically Canadian hockey player ever, he had not only his mother and sister with him but also a 24-year-old cabaret singer traveling under an assumed name. When he got his mother, sister, and would-be bride safely onto the lifeboats, he handed over a silver flask and sent them on their way. His body was never recovered, and that has got to be the most hockey-player way to die ever.

W.T. Stead

There's nothing about the life and accomplishments of W.T. Stead that isn't amazing, starting with how he could read both Latin and English when he was 5 years old. Oh, and he almost single-handedly pioneered the idea of investigative journalism.

The son of a minister, he took his steadfast morals to the streets and, more importantly, to the pages of London newspapers. In 1885, he rocked polite London society with a four-part series called "The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon," where he exposed London's seedy underbelly and its world of child prostitution. Not content to just repeat what he'd heard, Stead went undercover to "purchase" a 13-year-old girl, then published all the details on just how easy it was, and who was involved. He was actually arrested and imprisoned after the story ran, but his work ultimately led to a change in English law.

Stead believed that journalism should have an end goal, and that it wasn't just about bringing news to the masses. It was for inciting people to change the world for the better, a tool for social reform, and a way for people to shape their own government, calling out injustice and unfairness when they saw it. His work had such a large-scale impact that he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize more than once, and word on the street was that he was going to win it in 1912. That was, of course, the year he died on the Titanic, and his body (like so many others) was never found. One can't help but wonder what he would make of today's journalism, what changes he would suggest, and what choice, unprintable words he'd have for the Daily Mail.

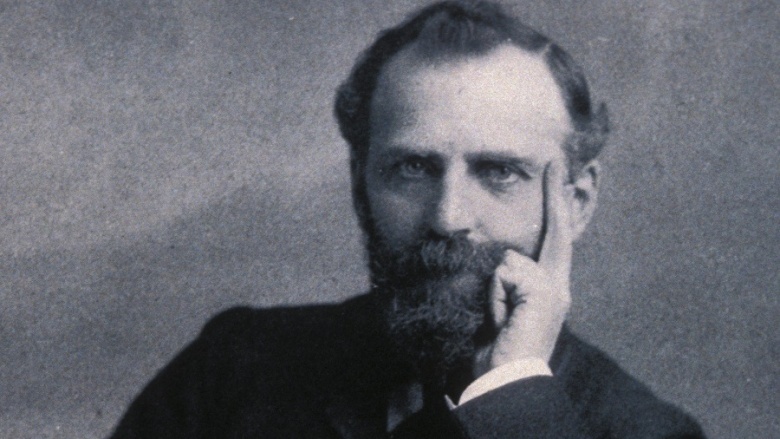

Francis Davis Millet

Francis Millet started out as a drummer boy and surgeon's assistant in the Civil War and later became a reporter and editor for the Boston Courier. It was his skill as an artist that got him the most recognition though, and by the time he devoted himself full-time to his artistic career, he was winning awards and recognition across Europe. Even as he acted as a war correspondent in the Russo-Turkish and Spanish-American Wars, he painted, observed, wrote, and collected.

That experience, along with the countless artifacts he brought home with him, led to him creating some of the most detailed and accurate murals and paintings of the time. His work is in London's Tate Gallery and New York City's Met, along with government buildings and churches across the country. His research notes, writings, and stories are in a collection in the Smithsonian, along with clothing and other artifacts he amassed during his travels to the Orient, Alaska, and Panama. He helped found Boston's School of the Museum of Fine Arts, and he was working as the head of a fine arts school in Rome when he headed to New York aboard Titanic.

Millet wrote perhaps the most epic description of the ship's passengers in a letter to a friend, saying, "Queer lot of people on this ship. There are a number of obnoxious, ostentatious American women, the scourge of any place they infest and worse on shipboard than anywhere." That alone makes us want to read more of his work.

His remains were later recovered, and he shares a memorial with his good friend, Maj. Archibald Butt.

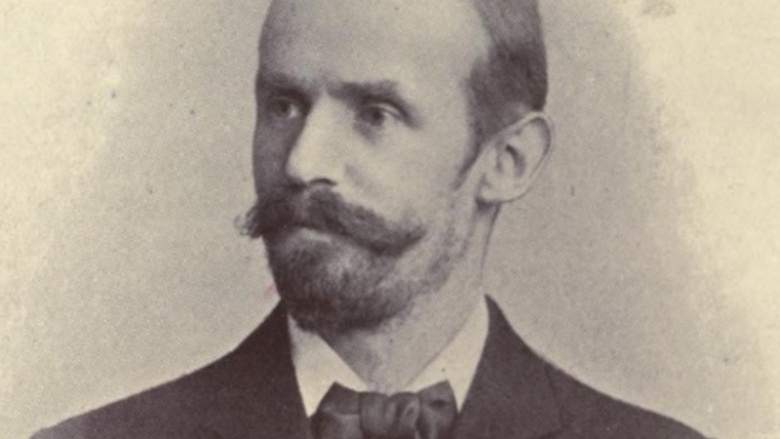

Jacques Heath Futrelle

You've heard of Agatha Christie, right? Jacques Futrelle's work is often credited with being her inspiration — before he died aboard Titanic, he wrote more than 40 stories about a detective called Professor Augustus S.F.X Van Dusen who, like Sherlock Holmes, was renowned for thinking around corners and unraveling even the most bizarre of mysteries.

Futrelle already had massive success stateside, and in 1912, he and his wife not only headed to Europe to negotiate the European release of his work but signed a handful contracts that would make any writer today willing to sell their soul. The contracts were worth thousands and, in order to celebrate his newfound global success, they booked passage back home on the most luxurious ship they could find – Titanic.

As the Titanic was sinking, Futrelle's wife got into one of the lifeboats, only leaving him because he promised to get into the next one. He never did, however, and witness reports say he was last seen standing on the deck with John Jacob Astor IV. After his death, his wife released two more stories that had been sitting, unpublished, when he died. She also issued a strange, heartbreaking lament (especially given his profession) — on the night before they left Southampton on the ill-fated ship, they had been having dinner and drinks with friends. She found herself wishing that he had gotten drunk, as they might have missed the boat then. She said that he never did drink enough. And thus marks the one and only time excessive drinking might've done a family, and the world, some good.