The Lethal Byford Dolphin Accident Of 1983 Explained

A scary fact of life is that anyone can die in a freak accident. However, few people are ever likely to be in a situation that could result in a death as freaky as that suffered by four of the five men killed on an oil rig in the North Sea in November 1983: explosive decompression.

Since humans tend to be perversely fascinated by the macabre, the Byford Dolphin accident is infamous for the sudden and terrible way the victims died, but there is so much more to the story than that. The reality is a painful tale of corporate greed, a decades-long cover-up, and families who were just as much victims as the men who were killed that day. While the horrible way these men died will always be the most well-known part of the story, out of respect for them, it should be understood in its proper context, as just one part of a much larger tragedy.

The following article includes descriptions of traumatic injury and death. Some images of the Byford Dolphin accident may be upsetting to view, and while we haven't included those images here, Grunge advises caution if you're searching for related information.

The pioneer divers of the North Sea oil boom

While it was known that there was oil and gas located under the North Sea as far back as the 1800s, it was not until 1964 that technological advances and changes in legislation made drilling for it possible. The early decades from 1965-1990, when the industry was new, are known as the "pioneer period." And much like other pioneers in history, those early oil rig workers found themselves in many dangerous situations.

The dangers became apparent almost from day one. In 1965, the first year companies attempted to drill in the area, a British Petroleum oil rig called the Sea Gem (pictured) collapsed. Of the 32 men on board, 13 died and another five were injured. The disaster led to some safety improvements, although they were so basic it seems unbelievable they had not been in place from the very beginning — things like regular inspections of oil rigs and organized chains of command on board the rigs. The fact that such important regulations had been overlooked was indicative of the way the oil workers would be treated in the pioneer period. As oil became more valuable, especially during the oil crisis of the 1970s, human life was cheap as long as companies made money.

In that 35-year period, 56 men were confirmed dead while working on oil rigs in the North Sea. While the majority were British, they came from four other countries as well, including eight American fatalities.

Before the accident

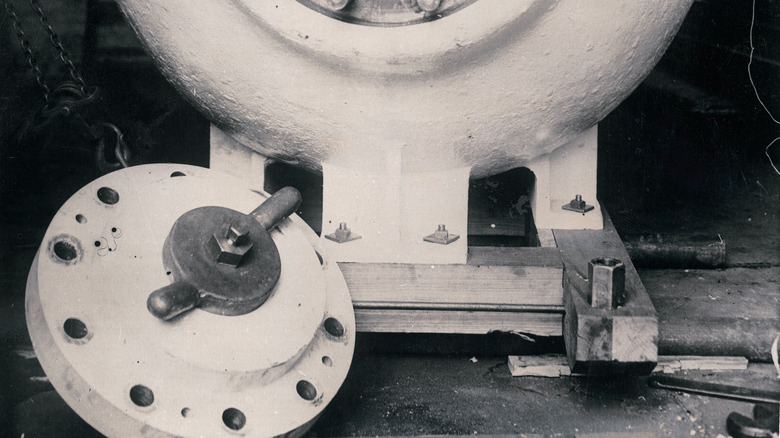

The Byford Dolphin was a mobile oil rig that was built in 1974. In 1983, it was located in the North East Frigg Oil Field in the North Sea, a section that was under Norwegian oversight, although the divers onboard were British and Norwegian, working for a French company. As saturation divers, their jobs involved entering a diving bell and being lowered into the sea, before entering the water in their dive suits to do whatever work was required. When finished, they would reenter the diving bell, which would then be attached to a decompression chamber on the rig.

On the day of the accident, November 5, 1983, there were six men involved in this task. It later became clear that these men had been worked to their limit over the past several months. Between August 15 and November 5, more than one-third of their dive shifts had gone over the eight-hour limit that was supposed to be enforced. This was not uncommon. There was no formal diver safety authority looking out for the men working in the North Sea from 1965 to 1978, and even once the Petroleum Directorate took on this responsibility, it had a reputation for being hands-off and pro-corporation, rather than actually looking out for the workers.

Adding to their exhaustion, diving that long for that often does horrible things to the human body, and at the time, workers on oil rigs were expected to just suck it up and deal with the effects of decompression sickness.

The event

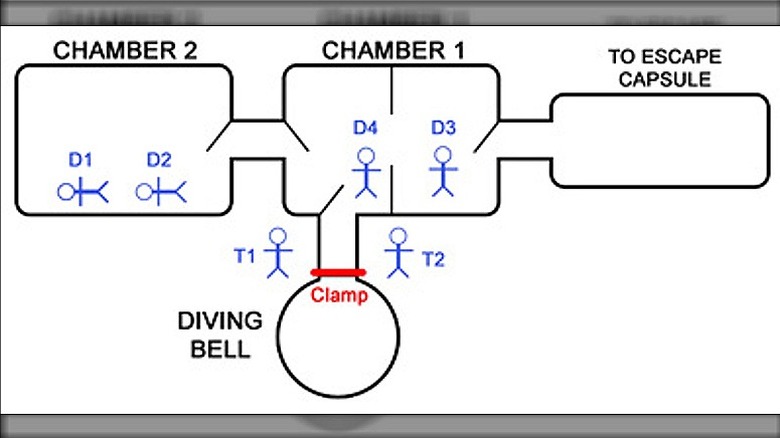

At 4 a.m. on November 5, 1983, two divers, Bjørn Bergersen and Truls Hellevik (D3 and D4 on the above diagram) reentered the diving bell after being in the sea for 2.5 hours. Decompression takes a while, so two other divers, Edwin Coward and Roy Lucas, who had been in the water previously, were resting in another section (D1 and D2). Outside of the decompression chamber, on the oil rig itself, were the two dive tenders, William Crammond and Martin Saunders (T1 and T2).

In an instant, four of the men were dead. Somehow, the clamp separating the decompression chamber from the regular atmosphere came undone, either by being moved too early by one of the dive tenders or by mechanical failure. The sudden and extreme change in pressure immediately killed the four men inside. Of the two men outside, Saunders was injured, and for a time, Crammond could not be found. It turned out that the explosive pressure shot him away from the chamber, and he was discovered suffering from fatal injuries after others on the rig went searching for him. Sadly, Crammond would die before reaching a hospital.

Two and a half decades later, Clare Lucas, the daughter of diver Roy Lucas, told Yorkshire Live, "Talking to people who saw it is virtually impossible because they have been so traumatized by it and can't speak about it."

The results of the explosive decompression were horrific

The four men who died inside the chambers were autopsied by the same group of pathologists. The paper they produced on their findings is a very difficult read, and the autopsy photos are nightmare-inducing. While the effects of explosive decompression on the human body are horrific, the only good news is that it's clear the four men all died instantly, so they would not have suffered. (This cannot be said for the dive tender William Crammond, who was hit by the diving bell and survived this blunt force trauma for a period of time before succumbing to those injuries, although his body was not sent to this group for autopsy.)

Three of the four divers had the same injuries to their bodies, namely, it was clear that the sudden change in pressure literally boiled their blood. The pathologists could tell this due to the large amounts of fat found in their bloodstreams and major organs. It was the fourth diver, however, whose death somehow managed to be even worse. It's believed he was closing a door between two sections of the decompression chamber when the event occurred, and the force pushed his body out through the opening — one far smaller than a body would normally be able to fit through. Parts of his body were found yards in every direction on the Byford Dolphin, and the pathologists note that they received his mutilated remains in several plastic bags.

The original report blamed human error

In the immediate aftermath of the accident, it became clear that one of the dead men was going to be blamed for the tragedy. A January 15, 1984, article in The Observer revealed a nut on the clamp was loosened, but it cited the opinion of a Norwegian official that this was not a mechanical error. The official said, "Since the nut was unscrewed, someone must have done it." However, the article also noted that the inquiry into the accident had not even started yet, so this assumption was premature at best and extremely unfair to a man who was no longer around to defend himself.

Nonetheless, William Crammond, the dive tender and a 32-year-old father of two, was assigned blame. Not only would the Crammonds not receive any compensation for the loss of William, but they were told he was at fault for mistakenly starting to unscrew the clamp between the diving bell and the compression chamber before it was safe to do so. This took a devastating toll on his family. His wife, Ruth Crammond, felt such enormous pain over the accusation that she wouldn't discuss what happened with her children for decades. She even fled her home in Scotland, telling BBC News, "I felt ashamed, I felt that people were crossing the road so they didn't have to talk to me, so I moved to England."

A new union fought to get justice for the Byford Dolphin victims for decades

While the Byford Dolphin accident would result in some changes to safety regulations on oil rigs in the North Sea, by the 1990s, it was clear to many divers working in that sector that no one was looking out for them. They formed the Nordsjødykker Alliansen or the North Sea Divers Alliance (NSDA).

The new union's goal was to get some form of justice for the men who had died or been injured working in the North Sea oil fields. Accidents like the Byford Dolphin happened in an area overseen by Norway, but even when the victims were citizens of that country, they almost never received the compensation they were entitled to. For any foreigner or their families, it was virtually impossible to qualify. This remained the case even after the union managed to get the Norwegian government to give financial compensation to about 200 divers or their families in 2004. In 2008, the NSDA's spokesman told The Times of London, "To apply for compensation you need a Norwegian identity number but most of the relatives of foreign divers were never given these."

While the Byford Dolphin accident was not the only tragedy the NSDA sought justice for, it was the most infamous incident. Eventually, the Norwegian government admitted they were morally and politically to blame for the deaths, but denied any legal responsibility. This was not good enough for the NSDA or the families.

Equipment failure was to blame but was covered up

It was not until the North Sea Divers Alliance managed to get ahold of the original report on the Byford Dolphin accident that they could prove the investigation had been little more than a cover-up that had resulted in an innocent man being assigned the blame for his own death and that of four others for two decades. In reality, it had been clear to inspectors from the beginning that this accident was due to equipment failure. The union tracked down the family members of the victims and let them know the truth.

They were shocked and angry. William Crammond's widow Ruth told BBC News, "Just six weeks ago, I found out that if a certain bit of equipment had been installed the accident would never have happened." Victim Roy Lucas' daughter Clare did not mince words when she told The Times of London, "I would go so far as to say that the Norwegian Government murdered my father because they knew that they were diving with an unsafe decompression chamber."

In 2008, despite the evidence being on their side, the families lost a court case seeking financial compensation in Norway. "I am angry and sad at the decision but I am not going to give up," Ruth Crammond told the Dunfermline Press. "All I am looking for is an apology and the truth to come out and clear Bill."

The victims' families finally received compensation in 2009

It took 26 years and several court cases before the loved ones the five Byford Dolphin victims left behind received compensation from the Norwegian government.

As Roy Lucas' daughter Clare made clear when speaking to Yorkshire Live, financial compensation mattered, because the country had profited hugely off the blood of the Byford Dolphin victims and the many others who died while working in the North Sea oil fields: "The Norwegian government turned a convenient blind eye to the activities of the diving company, who seemed willing to destroy the lives of divers and their families, all to provide the Norwegian government with a massive source of income." And she explained to BBC News why it was personal, saying, "These guys had no respect for human life; they were motivated by greed. My mum got no financial help for me and my brother and sister from the Norwegian government." The spokesman for the NSDA admitted one of the reasons he couldn't see finally getting the families compensation as a victory is how much they had suffered over the years, especially knowing how much difference the financial assistance would have made to them at the time.

However, money can only go so far toward making up for the injustice that these families suffered. Clare's brother Stephen Lucas told the U.K. newspaper the Journal (via the Commercial Diver Network), "We've never even received an apology and that's disgusting."