What Really Happened During The 1973 Oil Crisis?

Known as the First Oil Crisis, the 1973 oil crisis was one of the first moments of the 20th century when Western countries realized how much of a hold oil had on them. The use of it as leverage was even described as an "oil weapon."

And one of the most remarkable things about the 1973 oil crisis was the unique circumstances in which it took place, circumstances that are likely never to repeat again. Almost 50 years later, "posted oil prices no longer exist" and an oil embargo would have little effect due to the safeguards put into place. And even the Second Oil Crisis of 1978 bore little resemblance to the first, being instigated instead by the Iranian revolution.

But what exactly caused the First Oil Crisis and how did it have such an expansive impact? Although the United States is famous for the images of long lines of cars waiting to fuel up at the gas station, the effect of the oil crisis stretched from Brazil to Japan. Here's what really happened during the 1973 oil crisis.

Supporting Israel during the October War

On October 6, 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a joint attack on Israel, coming in from both the north and the south. Known as the October War or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, the offensive was in retaliation for the Third Arab-Israeli War in 1967, also known as the Six-Day War or the October War, during which Israel had captured and occupied the Egyptian Sinai desert, the Golan Heights in Syria, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, per Al Jazeera.

The attack was coordinated to occur during the Yom Kippur holiday that year, the only day during the year with no radio or television broadcasts in Israel, which is why the armed conflict is known as the Yom Kippur War. The fighting lasted from October 6 to October 25, and because it occurred during the month of Ramadan, the armed conflict is also known as the Ramadan War.

Both the United States and the Soviet Union supplied their respective allies with arms, the United States to Israel and the USSR to Syria and Egypt. And HistoryNet writes that although the U.S. and the USSR were both called by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat to send troops to enforce the ceasefire, armed forces were never explicitly sent over.

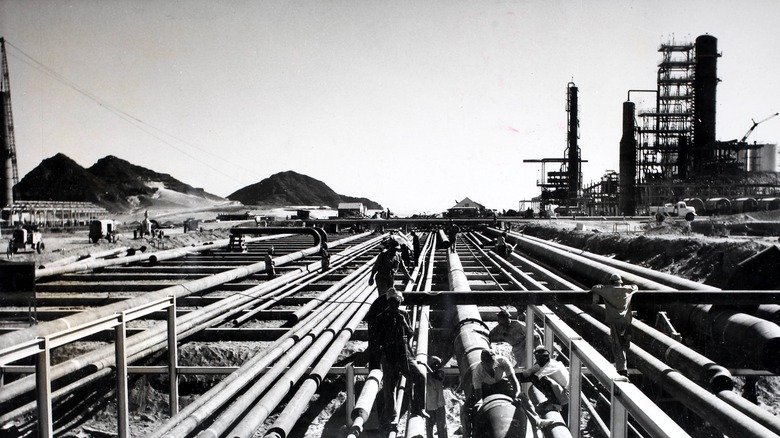

Oil production in Southwest Asia

After the Second World War, oil production in Southwest Asian countries rose substantially. According to the Journal of Economic Perspectives, between 1950 to 1970, the region went from producing 17% of the world's oil to 41%. However, the United States was the largest oil-producing country, and still is as of 2022, and was responsible for producing 25% of the world's crude oil.

Although the United States only imported between 5% to 12% of their oil from Southwest Asia, with some reports claiming the number was as high as 20%, according to "OPEC" by Mohammed E. Ahrari, other countries were heavily dependent on foreign oil imports. Western Europe imported 45% of their oil from Southwest Asian countries and Japan imported up to 88%.

In The Road to America's First Energy Crisis, Jay Hakes writes that between 1967 and 1973, Southwest Asian countries "more than doubled their output to 14.8 million barrels a day." Meanwhile, during this time, oil demand rose in the US by 30%.

OAPEC & OPEC

The Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) was created on January 9, 1968 by Kuwait, Libya (known as the Kingdom of Libya at the time), and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Within five years, they were joined by Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, Syria, the United Arab Emirates, and the Emirate of Bahrain, now known as the Kingdom of Bahrain. This is not to be confused with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which was created on September 14, 1960 by Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela.

According to "OPEC: The Failing Giant," "an original, explicit purpose of OAPEC was to keep the oil question out of politics" and it was formed in response to the failed 1967 oil embargo that several Southwest Asian countries attempted during the Six-Day War. Meanwhile, OPEC was created to "secure fair and stable prices for petroleum producers." However, it soon became apparent that politics and oil were inextricable.

Cutbacks and embargos

During the October War, OAPEC decided to use oil as a way to influence support. According to "OPEC: The Failing Giant," this was part of a "triple-barreled strategy" of restrictions, which involved not antagonizing countries that were friendly, enticing countries that were neutral, and punishing those who were perceived as "allies of Israel."

Starting on October 17, 1973, OAPEC began imposing its restrictions. One of the resolutions involved cutting oil production "until the Israeli withdrawal from Arab territories occupied since 1967 was complete and the legitimate rights of the Palestinians were restored," Ahrari writes. In addition to cutting oil production by a minimum of 5%, later raising the cutbacks to 25%, an embargo was issued against several countries including the United States, Japan, and the Netherlands. Countries like Belgium and Japan were considered "semiembargoed nations."

OAPEC also wasn't acting alone, but this may not have necessarily been intended to be a coordinated effort. On October 16, OPEC raised the price of oil barrels, which inevitably exacerbated the impact of the production cuts and embargos. But according to "Arab Nationalism, Oil, and the Political Economy of Dependency" by Abbas Alnasrawi, this price increase wasn't a new idea. OPEC and the oil companies had a negotiation scheduled regarding oil prices for October 8, for which OPEC had stated their intention to raise the price from $3 to $5. But when oil companies refused to agree to the price increase, it led OPEC "to set the new price unilaterally" at $5.12 per barrel.

A six-month embargo

The oil embargo lasted from October 1973 to March 1974, though in some countries, like the Netherlands, it continued until July 1974. During the months of the oil embargo, numerous countries felt an impact, but the oil embargo wasn't all-compassing. In "A History of Saudi Arabia," Madawi al-Rasheed writes that the embargo was only "partially enforced" and overall, "the United States suffered a deficit of about 12% of its total supply." And Iran, whose leader Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was a U.S. ally, continued to produce and export oil throughout the embargo, according to NPR.

Ultimately, the embargo can't really be considered a success since neither of the conditions regarding Israel's withdrawal or Palestinian rights were fulfilled. However, numerous countries, including the United States, were affected enough by the embargo that it established the status of OAPEC and OPEC, which had up until then been "virtually ignored." Even Kuwaiti oil minister Abdullatif Al-Hamad was surprised, stating, "You don't realize that on the 16th of October, we got as great a shock as you did. We thought we were pygmies facing giants. Suddenly we found that the giants were ordinary human beings," per Strategic Analysis.

Gas prices skyrocket

Due to the rising prices of oil barrels, prices for gasoline skyrocketed. In the United States, the national average price for gasoline went from 38 cents to 55 cents by June 1974, according to GEO ExPro. Drivers watched as it cost twice as much to fill up the tank of their car than it had during the same time last year. The United Kingdom also saw their gasoline prices double and in Italy, the price "more than tripled." By the end of the oil embargo, OPEC had raised oil prices to almost $12 per barrel.

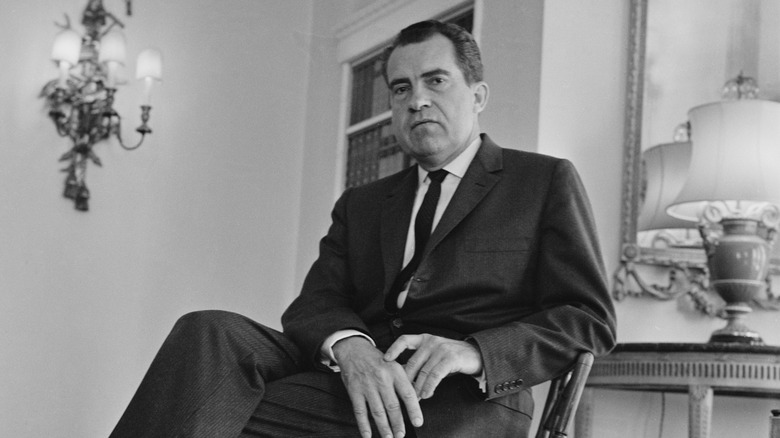

In "Gerald Ford and the Challenges of the 1970s," Yanek Mieczkowski writes that in the United States, the price of gasoline and heating oil went up by 33%. Meanwhile, President Richard Nixon tried to placate the nation, stating that "Scare stories that the American people will soon be paying a dollar for a gallon of gas are just as ridiculous as the stories that say that we will be paying a dollar for a loaf of bread." Needless to say, Nixon was wrong on both counts.

And consumers weren't the only ones feeling the economic shock. According to The New York Times, shares at the New York Stock Exchange lost $97 billion in value in November 1973 alone.

Daylights saving and speed limits

During the 1973 oil crisis, the United States instituted two policies to try to cut down on the use of oil: daylight savings and speed limits. The Emergency Daylight Saving Time Conservation Act of 1973 was signed by President Nixon in December 1973 and went into effect on January 6, 1974, with clocks being set ahead by an hour.

Nixon claimed that being on daylight savings time would "result in the conservation during the winter months of an estimated equivalent of 150,000 barrels of oil a day," per The American Presidency Project. Although this was intended to save on lighting costs, in some parts of the United States this meant that public schools had to begin before sunrise.

Nixon also signed the Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act on January 2, 1974, which imposed a 55 mph speed limit "on all state and interstate highways" across the country. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, Nixon estimated that the new speed limit could save up to 200,000 barrels of oil per day. The federal speed limit remained in effect until December 1995, when it was removed by the National Highway System bill, reports Associated Press.

The Emergency Petroleum Allocation Act

Another bill signed into law by President Nixon was the Emergency Petroleum Allocation Act of 1973 (EPAA). According to Annual Review Energy, with this act, Congress granted the President with the temporary authority to establish "a program of mandatory allocation of crude oil and products" as well as price controls.

These price and allocation controls were meant to address nine objectives, including the protection of public health, the "preservation of an economically sound and competitive petroleum industry," and the preservation of economic efficiency. Ultimately, the regulations ended up "controll[ing] nearly all aspects of the petroleum industry and markets."

The EPAA ended up being "massively dysfunctional," write Robert R. Nordhaus and Sam Kalen in "Energy Follies." "Price controls reduced incentives for conservation and did not provide effective incentives to increase domestic oil production from existing fields, and the allocation system at times made petroleum shortages worse." And yet, in "Energy Use in Transportation Contingency Planning," George Horwich notes that although the EPAA was meant to expire in February 1975, Congress extended the President's authority four times until the EPAA finally expired on September 30, 1981.

Gasoline rationing in the United States

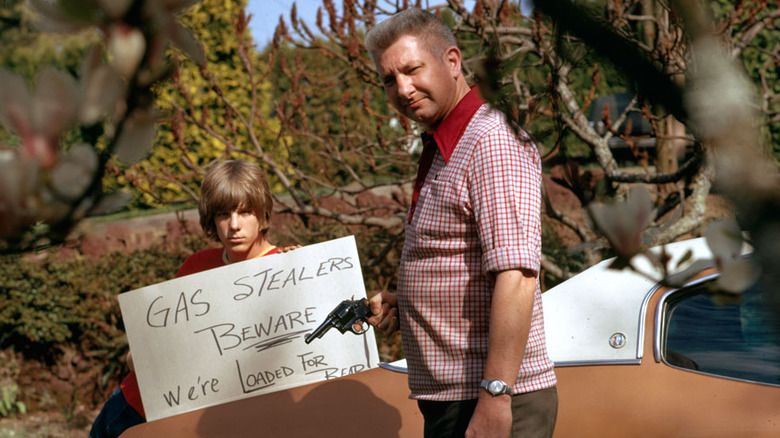

In addition to high gasoline prices, it also became difficult to get gasoline. NPR writes that gas stations often had lines of drivers that went around the block. In an attempt to avoid the lines, some drivers would go to refill the tank in the early hours of the morning. The Baltimore Sun reports that some lines would be up to 5 miles long.

Gas stations used a color-coded flag system to let drivers know if they had gas; green if they had it, red if they were out, and yellow "if rationing was in effect." According to Smithsonian Magazine, some gas stations "illegally sold to regular customers only." Overall, tensions started running high and some gas station owners began carrying guns in response to fights breaking out more. In states where the oil shortage was most acute, gasoline was rationed through license plate numbers: "Drivers whose license plates had an odd number could purchase gas on the odd-numbered days of the month and those whose plates had an even number could purchase gas on the even days of the month."

On December 28, 1973, the Federal Energy Office announced that gasoline rationing coupons were to be printed. Between January 25 and March 20, 1974, almost five billion coupons were printed. But according to the National Postal Museum, due to the conclusion of the oil crisis in March 1974, the coupons were never used.

State-specific solutions

Some states in the United States tried their own unique solutions to try to cut back on oil use. In Alaska, parking lots were only plowed halfway to force people to carpool and in Oregon, all the hot water in state buildings was shut off.

Christmas lights also became a symbol of the fuel crisis, with different cities responding in various ways ranging from not using lights at all to hanging them up unlit. However, according to The New York Times, there wasn't any uniform enforcement. In California, for example, although the city of Los Angeles chose to forgo holiday lighting, Disneyland remained illuminated, with a spokesman saying, "We don't want to disappoint thousands of visitors."

A campaign known as "Don't Be Fuelish" was used in many advertisements and public service announcements, using the phrase to remind people in the United States to conserve the use of fuel.

Considering the seizure of oil fields

During the middle of the 1973 gas crisis, the United States reportedly gave "serious consideration" to sending troops to seize oil fields in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Abu Dhabi. The Washington Post reports that a declassified British intelligence memorandum dated December 13, 1973, explores the possibility of an American seizure of the oil fields, stating that "we believe the American preference would be for a rapid operation conducted by themselves."

The document goes on to estimate the amount of force necessary for the occupation and, according to Al Jazeera, noted that the occupation would have to last up to 10 years.

However, it's unclear if the United States would have actually gone through with such a seizure. In "Oil Powers," Victor McFarland writes that Secretary of State Henry Kissinger reportedly told his staffers on one occasion, "I know what would have happened in the 19th century. But we can't do it. The idea that a Bedouin kingdom could hold up Western Europe and the United States would have been absolutely inconceivable. They would have landed, they would have divided up the oil fields, and they would have solved the problem. That obviously we cannot do." But on another occasion, Kissinger complained, "Can't we overthrow one of the sheiks just to show that we can do it?"

Japan and foreign oil

Another country that was severely affected by the 1973 oil crisis was Japan, which, unlike the United States, imported the majority of its oil. In "Energy Security in Japan," Vlado Vivoda writes that it's been suggested that "no nation was more profoundly affected by the 1973 oil crisis than Japan." With oil prices quadrupling and operating under a semi-embargo, Japan felt the harshest effects of OAPEC and OPEC's restrictions.

The Japan Times reports that as companies "scrambled to secure fuel and petroleum-related materials," consumers rushed to stock up on "toilet paper and detergent," operating under the assumption that if oil supplies were disrupted, then daily necessities would also be scarce. And compared to the United States, which saw a 4.7% drop in GDP, and Europe, which saw only a 2.5% drop, Japan saw a 7% drop in GDP due to the oil crisis.

The oil crisis had such an effect on Japan that it immediately started to diversify its energy sources and reduce its dependence on oil, investing instead in natural gas and nuclear. However, although in 2010 Japan was only using oil for 43.7% of its energy supply, Southwest Asian oil still accounted for more than 80% of oil imports.

Western Europe and foreign oil

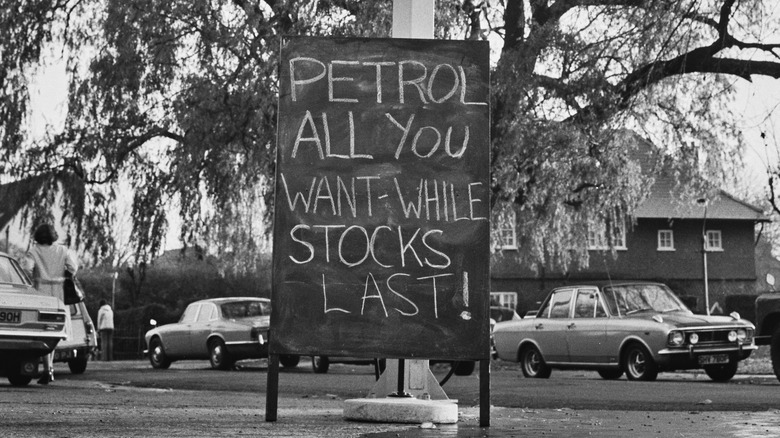

Countries in Western Europe similarly saw a severe impact during the oil crisis, impacted by both the high prices as well as the embargo. According to The Conversation, Sweden instituted rations for heating oil during the wintertime and in the Netherlands, "excessive electricity use" was punished with a prison sentence.

Targetting the Netherlands was also critical not only because of their pro-Israel stance but because of the position the Netherlands occupied within the petroleum industry in Europe. Not only was the Netherlands the birthplace of Royal Dutch Shell, also known as Shell plc, but Rotterdam was "a crucial switch-point in the whole circuit of the processing and distribution of oil in Western Europe," according to "The Netherlands and the Oil Crisis."

In "The Politics of the Global Oil Industry," Toyin Falola and Ann Genova write that the effects were "less dramatic" in places like the United Kingdom and France because the governments "made special deals" with Southwest Asian countries to make sure that there was a continuous supply of oil. Meanwhile, many European countries prohibited driving on Sundays, according to "European Banks and the Rise of International Finance" by Carlo Edoardo Altamura, and Germany implemented governmental control of energy supplies.

Legacy of the oil crisis

Although the flow of oil resumed after OAPEC lifted the embargos, the oil prices set by OPEC continued to remain long after the oil crisis had concluded. According to Resources, prices continued to rise until they stabilized around $50 per barrel. During the 1978 Iranian Revolution, they doubled to $100 per barrel and it would take until the mid-1980s for the price of oil to drop back down to $30 per barrel.

But ultimately, there wasn't as much of a limited supply of oil during the oil crisis as has often been portrayed. The Journal of Economic Perspectives writes that the oil crisis was "actually was driven by increased demand for oil rather than reductions in oil supply." While the oil embargo was meant as a sanction against the U.S. providing Israel with arms, the increased oil prices and reduced productions were "motivated by the cumulative effects of the dollar devaluation, unanticipated U.S. inflation, and high demand for oil fueled by strong economic growth."

The oil crisis also brought on a change in attitude towards energy conservation and alternative energy, including renewable energy like solar and wind. Although this enthusiasm would fade as oil prices fell during the 1980s, energy-efficient standards such as wall installation, double-glazed windows, and programmable thermostats would remain.