Things About The OJ Simpson Case That Still Don't Make Sense

In the mid-'90s, the entire world was captivated by the morbid spectacle of what came to be known as the "Trial of the Century" — the murder trial of O.J. Simpson, the beloved Hall of Fame NFL running back, movie star, and pitchman whose good looks, genial manner, and innate charisma had given him a fruitful career long after his retirement from the gridiron. The crime he was accused of was exceedingly brutal — the stabbing deaths of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ronald Goldman. His behavior in its aftermath, maintaining innocence while acting for all the world like a guilty man, was as puzzling as the murders were shocking. His trial, the first such high-profile proceedings to be nationally televised, made for a riveting national drama in 1994 and 1995.

The broad details of the case are well-known: Simpson, represented by a "dream team" of celebrity attorneys, was acquitted after the year-long trial but was subsequently found liable in a civil trial and ordered to pay $33 million to Goldman's family. Three decades later, though, there are still a slew of details about the case that don't make any sense to the general public — and while some of these can be explained somewhat adequately with the benefit of hindsight, many others are simply confounding.

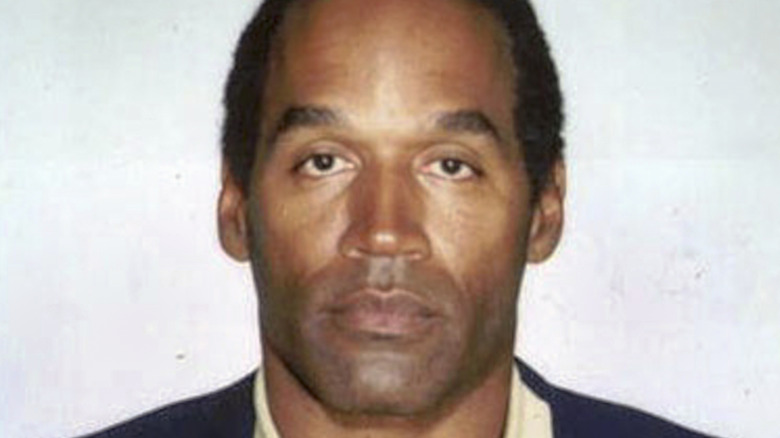

O.J. Simpson wasn't arrested right away

The murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman occurred sometime between 10:00 p.m. and 11:00 p.m. on June 12, 1994; shortly after 11:00 that night, O.J. Simpson got into a waiting limo, which was taking him to Los Angeles International Airport to board a flight to Chicago. The bodies of his ex-wife and Goldman were discovered shortly after midnight, and by noon on June 13, O.J. Simpson was back in Los Angeles, where he was questioned by police — but not arrested. In fact, he wasn't arrested until four days later, on June 17 — even though police had noted the presence of bloodstains on his white Ford Bronco and had discovered a glove on his property that seemed to match one found near the bodies.

To an outside observer, it might seem ludicrous not to place O.J. under arrest — but the reason for this is probably the most obvious one, as explained by UCLA law professor Peter Arenella in an analysis of the case by PBS. "The problem ... was Mr. Simpson's celebrity status," he explained. "His celebrity status explains why he wasn't arrested very early on in the case when the average defendant, given the blood evidence, would have been arrested immediately ... the detectives handled him not like a criminal suspect, but like a celebrity."

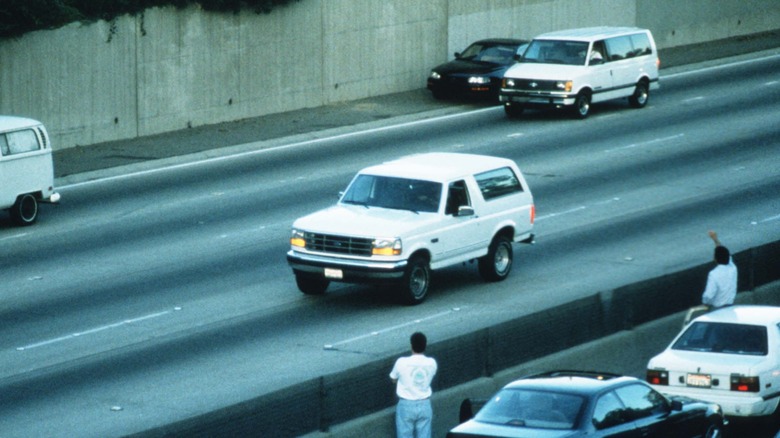

The Ford Bronco police chase

In the early afternoon of June 17, the police announced that O.J. Simpson was indeed a suspect in the murders, and that they were actively seeking to bring him in. For a few tense hours, it actually appeared as though one of the most beloved figures in U.S. sports history might go on the lam from the authorities — until about 6 p.m., when Simpson himself called 911 to report his whereabouts. Those whereabouts: in the back seat of a white Ford Bronco belonging to his friend Al Cowlings, heading at a leisurely speed down the freeway, a gun to his head and Cowlings behind the wheel.

For the rest of that evening, local and national news covered the unfolding drama as Simpson, threatening suicide, slowly made his way toward his Brentwood estate. The chase was watched by millions of people — people who had to wonder, months later, how Simpson could possibly plead not guilty to the crimes when his actions on that surreal day seemed to so clearly broadcast his guilt. Years after the fact, in an interview for Fox TV shot in 2006 but not aired until 2018, Simpson explained himself by saying that he had watched all of the considerable public goodwill he had amassed over the years suddenly disappear, and that when his ex-wife and her friend were killed, "it's almost like they killed me — who I was, was attacked and murdered, also."

Why was the trial's venue changed?

It has long been thought that, at the behest of District Attorney Gil Garcetti and the prosecution team, O.J. Simpson's murder trial was moved from Santa Monica, where the crime took place, to downtown Los Angeles, and for a pretty specific reason: to avoid the appearance of bias, as Santa Monica is predominantly white. Indeed, Simpson ended up with a jury predominantly composed of eight Black jurors — but according to William Hodgman, one of the lead prosecutors on the case, the notion that the prosecution was trying to avoid having their famous, Black client tried in front of a mostly white jury is a misconception.

Speaking with PBS, Hodgman explained that at that time, most major cases in the entirety of Los Angeles County — including most of the murder cases — were being tried downtown, and by filing charges against Simpson there rather than in Santa Monica, the prosecution was basically just cutting to the chase. "We could have very well filed the case in Santa Monica," he said. "But by practically filing the case where we knew it was going to end up ... It was the practical awareness that the case was going to be tried here, so let's not beat around the bush." Hodgman lamented that "some people felt that that was pandering to the Black community by [filing the case downtown]. It had nothing to do with that at all."

The prosecution took a long time to present their case

Prosecutors Marcia Clark and Christopher Darden ran point on the trial, and to attorneys monitoring the case, it quickly became apparent that they may not have had the most focused strategy. They opened not with the physical evidence against O.J. Simpson — the blood in his Ford Bronco that was found to be a mixture of his and the victims', the glove found on his property, and hair and footprint evidence found at the crime scene — but on Simpson's alleged history of domestic violence against his ex-wife. It was an opening volley that foreshadowed a troubling tendency by the prosecution to get lost on tangents, belabor relatively trivial points, and fail to clarify their most important ones — tendencies that Judge Lance Ito failed to rein in time and again.

Unfortunately, as pointed out by author and attorney Scott Turow during a conversation with PBS, the prosecution's seeming inability to focus caused the trial to drag on far longer than it should have — over a year, making it the longest criminal trial in California history. "They took six months to present the evidence against O.J. Simpson," Turow said. "And when it takes you six months to make your case, the jury is going to be left with either one of two impressions: Either your evidence is overwhelming, or ... you're laboring day by day to make it appear to be better than it is. And unfortunately in this case, it was the latter impression that the jury got left with."

Putting Mark Fuhrman on the stand

Ordinarily, the testimony of the first cops to arrive on the scene of a murder would be invaluable — but the prosecutors in the O.J. Simpson trial made a grave error in relying on the testimony of Mark Fuhrman, who was the kind of witness for whom the word "problematic" was invented. Fuhrman was called to testify largely about the evidence collected at the scene; crucially, he was the one who found the bloody glove on Simpson's property. During his testimony for the prosecution, he performed well — but when he came under a blistering cross-examination by the legendary attorney F. Lee Bailey, things fell apart quickly.

At one point, Bailey asked Fuhrman whether he had ever used the N-word, with Fuhrman replying that he had not. Unbeknownst to him, Simpson's defense had receipts: hours of interviews between Fuhrman and an aspiring screenwriter, during which Fuhrman spewed racial slurs, condoned excessive force and falsifying reports, and boasted that it would be no sweat for a cop to get away with murder. Fuhrman was now facing perjury charges, and suddenly, the defense's assertion that Fuhrman had planted the glove on Simpson's property didn't seem so far-fetched. When he was later recalled to the stand to testify about whether he ever planted evidence, he invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination in response to all queries. Speaking with PBS, prosecutor William Hodgson acknowledged that his team knew Fuhrman was problematic — but inexplicably chose to take their chances.

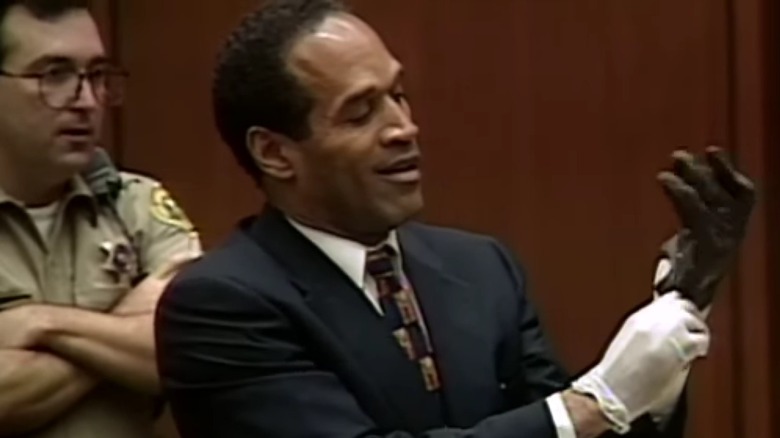

When O.J. Simpson tried on the gloves in court

Even more inexplicable was the trial's single most dramatic moment: a courtroom demonstration masterminded by prosecutor Christopher Darden, who pretty much bet the house on the bloody gloves found at the crime scene and at O.J. Simpson's estate being the smoking gun. Following Mark Fuhrman's testimony regarding the gloves, the prosecutors asked Simpson to get up from the defense table and put the gloves on — what happened next would go down in legal history as perhaps the biggest mistake any prosecuting attorney has ever made.

As Judge Lance Ito instructed Simpson to move toward the jury, Simpson visibly — and rather dramatically — struggled with them. Speaking with Law & Crime, Dan Abrams, a Court TV reporter at the time, summed up the demonstration. "No one could believe that [the prosecutors] were actually going to do it since it was such an enormous risk," he said. "We assumed if they were moving forward with it they must know that it's going to fit ... but the exasperation on the face of Chris Darden told us everything we needed to know. Disaster." To say that the demonstration backfired would be an egregious understatement; not only did the jury get a made-for-TV moment that further cast doubt on Fuhrman's testimony, but the Simpson's team was handed a killer punchline for defense attorney Johnnie Cochran's closing argument: "If it doesn't fit, you must acquit."

Why was the famous Bronco chase not introduced as evidence?

Among the mountain of circumstantial evidence to be presented by the prosecution, one would think that O.J. Simpson's long, tense journey in his Ford Bronco on the day of his arrest would be the most compelling to be heard by the jury; after all, innocent men don't often run from the police or threaten to kill themselves, and as the defense slowly, methodically planted the seeds of reasonable doubt in the minds of the jury, the Bronco chase might have at least plucked up a few before they had the chance to fully bloom. It might have, that is, if not for one small problem: It was never introduced into evidence at all.

It wasn't just the fact of the low-speed chase that the jury didn't get the chance to consider; there was also the small matter of the $8,750 in cash, fake beard, and passport that were found in the vehicle after Simpson's arrest — items that obviously indicated that despite Simpson's dramatic suicide threats, he may have been planning to flee the country. Incredibly, although the prosecution mulled over the possibility of presenting it, they simply chose not to, with District Attorney Gil Garcetti telling the Los Angeles Times that "the evidence that has been presented to the jury by both sides is sufficient ... We're paring this rebuttal evidence down to the absolute minimum."

Key witnesses weren't called to the stand

Incredibly, the prosecution's failure to present compelling information to the jury extended beyond evidence. A pair of witnesses, both of whom were willing to testify, were passed over by prosecutor Marcia Clark: Jill Shively, who nearly got into a car accident with Simpson as he was allegedly speeding away from the scene of the crime; and Skip Junis, who spotted Simpson at Los Angeles International Airport disposing of something he was carrying in one of his travel bags.

In the case of Shively, Clark declined to have her testify after she appeared on the tabloid TV show "Hard Copy," having sold her story for $5,000; she said that Simpson, like "a madman gone insane," was screaming through the streets at a high rate of speed and blazed through a red light as she watched. A livid Clark dropped plans to put her on the stand, feeling she had blown her own credibility with her actions. As for Junis, he would later tell "Inside Edition" (via Yahoo! News) that he had no earthly idea why he wasn't called to testify. "It haunts you that I may have seen him you know discard crucial evidence," he said. "I called the defense and prosecution, if they had only known they could have searched the waste."

Cops faced allegations of evidence tampering

To this day, it is not known whether Mark Fuhrman or any other investigators actually planted any of the evidence against O.J. Simpson; given the seemingly open-and-shut nature of the case, it doesn't make much sense on the surface for them to have done so. But a great deal of defense testimony was dedicated to poking holes in the physical evidence, such as a bloody sock that a defense expert testified was likely not being worn when it came into contact with blood — and the defense's strong implications that evidence may have been planted was certainly not helped by Mark Fuhrman's pleading the fifth when confronted directly about the possibility.

If the police believed Simpson was guilty, though, then why manufacture evidence against him? Speaking with PBS, Simpson defense attorney Shawn Chapman Holley put forth a plausible hypothesis. "[The police] helped the evidence along. I don't think that they thought he was innocent, and that they were trying to frame him," she said. "I think they thought he was guilty, and they were trying to make their case a little more airtight. What they weren't counting on [was Simpson's] defense team ...being able to find where they framed him and the mistakes that they made."

The prosecution didn't emphasize the DNA evidence

For all of the tangents explored and ill-advised areas of inquiry O.J. Simpson's prosecutors became sidetracked with, it's fair to say that perhaps their strongest card was one that went severely underplayed: the DNA evidence. Forensic scientist Gary Sims tesified that the blood samples found in OJ. Simpson's Bronco were a match for O.J. Simpson, Nicole Brown Simpson, and Ronald Goldman — whom O.J. had never met before the night of the murders, making this evidence particularly compelling. During her closing argument, Marcia Clark did mention the presence of Goldman's blood in the Bronco — amid a storm of information, much of which was completely unrelated to that evidence.

Prosecutor William Hodgman expressed in his chat with PBS that the team had been confident, perhaps overly so, in the jury being able to follow them as they painstakingly painted a picture involving myriad evidence, both physical and circumstantial, over the course of the grueling trial. Indeed, during Christopher Darden's closing argument, he simply repeated many of the dizzying array of details Clark had already hammered the exhausted jurors with, failing to drive home her point about the crucial DNA evidence.

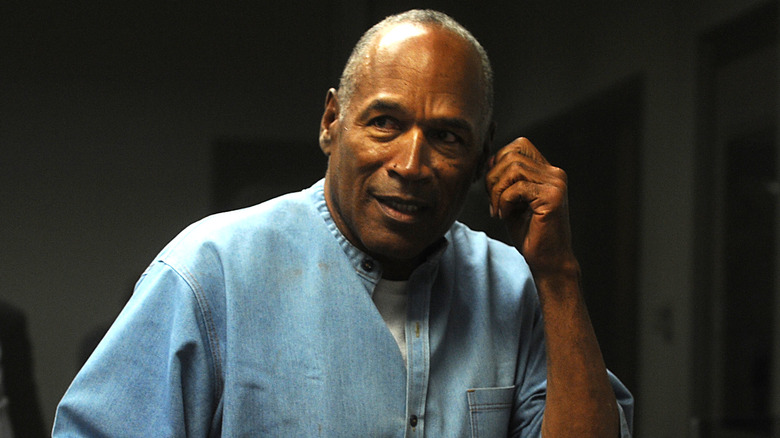

O.J. Simpson was acquitted

Today, it's safe to say that most impartial observers believe that there is, at the very least, a fair chance that O.J. Simpson is guilty of the murders of his ex-wife and her friend. How, then, was he acquitted? While the trial's outcome obviously hinged on a variety of factors, the legal experts who spoke with PBS for their analysis of the case seemed to agree that, somewhat fittingly, a football analogy might best explain Simpson's acquittal: The determined, experienced defense came ready to play. The overconfident, inexperienced prosecution did not — and Simpson's "Dream Team" was essentially able to game a flawed system.

One member of that team, though, doesn't see it that way. Alan Dershowitz, one of Simpson's attorneys, opined during his sitdown with PBS that the Simpson case was one in which the system actually worked too well for the comfort of those watching the trial unfold on their TV screens. "The public doesn't like the system," he said. "The public much prefers the old system ... in which the prosecution really doesn't have to prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt; the prosecution really doesn't have to abide by the Constitution; the prosecution really doesn't have to play fair with all the evidence. The public saw the system working, and they didn't like it."

Why did O.J. Simpson write a hypothetical confession?

So, consider: What if O.J. Simpson is indeed innocent? It's certainly not beyond the realm of possibility, and it's tough to say what any one of us would do if we suddenly found ourselves accused of a horrifying crime we did not commit. There is one thing, though, that it's safe to say not many of us would do — write a book about how we would have committed the crime we were falsely accused of, if, you know, we had actually done it. This, though, is exactly what Simpson did; in 2007, he announced a book originally titled "If I Did It, This is How It Happened."

Simpson's Fox TV interview, recorded shortly before the book's planned release but not aired until a dozen years later, featured his first-person account of just how it might have happened — a "hypothetical confession" that, at many points, seems anything but hypothetical. The book's release was blocked, and in a stunning twist, a bankruptcy court awarded its copyright to the family of Ronald Goldman, who published it under the title "If I Did It: Confessions of the Killer," with a preface by Goldman's sister Kim. Simpson's stated reason for writing the book was to provide financial security for his and Nicole's children — but now, any proceeds will go to satisfy the Goldmans' civil judgment against him.