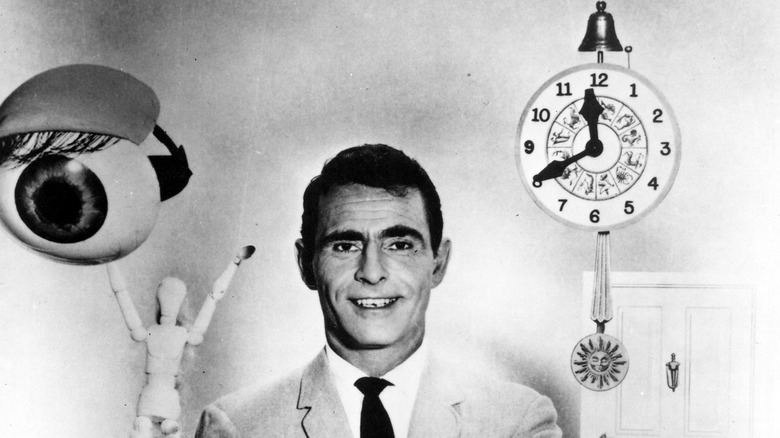

The Tragic 1975 Death Of Rod Serling Explained

Rod Serling, the man who'd created the legendary "Twilight Zone" television series, lay in bed staring death in the face. The garish yellow and green walls of the hospital room at the Strong Memorial Hospital in Rochester, N.Y., contrasted with the small figure under the white hospital sheets who was slowly succumbing to the inevitable.

He'd faced death before, as a U.S. Army paratrooper fighting the Japanese in the Philippine jungles during World War II. He had a limp for the rest of his life after getting hit by shrapnel. "I was convinced I wasn't going to come back," he said after the war (via "Rod Serling: His Life, Work, and Imagination"). But this was different. He wasn't 18, he was 50 and had just undergone a 10-hour-long heart surgery during which he suffered his third heart attack in a little more than a month. Unlike many of the unforgettable episodes of his famed television show, there would be no surprise ending for Serling. He died on June 28, 1975.

Health issues

Rod Serling was born December 25, 1924, in Syracuse, New York but grew up an hour south in Binghamton in a Jewish family. He was athletic in his youth, briefly took up boxing, and had considered a career in athletics before he decided to pursue writing. He was tough, having survived the brutal Philippines campaign during World War II. But a family history of heart problems, his bad habits, and an intensive work schedule all added up to an early death for the famed television writer and presenter.

His father died of a heart attack at age 52, while Serling was still overseas in the U.S. Army at the end of the war in September 1945. Serling was also a heavy smoker with a three- to four-pack-a-day habit. This is demonstrated in reruns of "The Twilight Zone" in which Serling introduces each episode of the science fiction anthology series with an ever-present cigarette. Additionally, the show that helped immortalize Serling also pushed him closer to the grave. "It's been a back-breaking, torturous schedule, and both my health and my point of view have suffered irreparably as a result of it," he wrote to CBS executives during the 2nd season of "The Twilight Zone."

Open-heart surgery

By 1975, Rod Serling had all but given up his television career. He was much happier teaching creative writing at Ithaca College in upstate New York. "There was a time when I wanted to reform television," he said in 1970 (via The New York Times). "Now I accept it for what it is. So long as I don't write beneath myself or pander my work, I'm not doing anyone a disservice."

That May, he was exercising on his treadmill when he had a heart attack, which was described in the press as a "minor myocardial infarction." The next month, he was back in the hospital in Syracuse with chest pains. He had suffered a second heart attack while at his vacation house in New York's Finger Lakes. Serling was still a household name and the press followed his health crisis, closely reporting his status from his first hospitalization to his last. As Serling lay in the hospital, he put down his thoughts on the tediousness of being bedridden. "The days are infinitely longer in the hospital, not only in chronology and in time passing but also in the actuality of the event," he said (via "As I Knew Him: My Dad, Rod Serling"). "They start early and last a long time."

Death and funeral

As Rod Serling headed to his end, the six-time Emmy-award-winning writer's earlier fears of death faded. "What I do have is the terrible awareness of how little time there is to accomplish so many of the things that you want to accomplish," he said. The doctors did their best to keep him alive, but it wasn't enough. The 50-year-old left a wife, Carol, and two daughters, Anne and Jodi, behind. They had his body cremated and on a summer day in July, they and about 200 others celebrated Serling's life at Sage Chapel on the Cornell University campus. Per the Associated Press, a Unitarian pastor at the ceremony talked about Serling's "wisdom, tempered with fallibility, and feisty courage, laced with wit."

Serling didn't think his work would be remembered much less admired. "I've pretty much spewed out all I have to say, none of which has been particularly monumental, nothing that will stand the test of time," he said not long before his death. He hoped that when people heard his name, they would at least recall that he had been a writer. They remember much, much more than that of the brilliant creative force whose work still resonates today.