How Rod Serling's World War II Military Service Fueled The Twilight Zone

"Submitted for your approval: one Rod Serling, homo sapien, who from the shattering grip of war's burn and bluster returned to his fellow man, only to find himself snared within visions of an unreal society torn into fraudulence by its battlefield twin, in a wreck carried on a stretcher to a realm of truth and sense that can only be described as... The Twilight Zone."

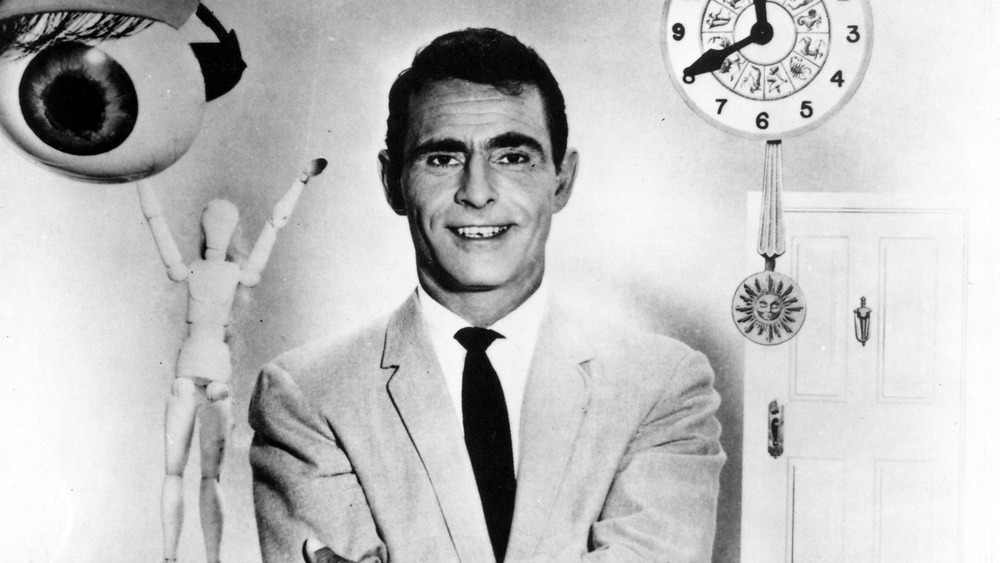

Yes, in Rod Serling's own gumshoe voice, jaw askew, cigarette in hand, we can imagine him author the origin of his groundbreaking, multi-generation-defining TV series, The Twilight Zone: war. When TZ first aired in 1959, it was a series truly ahead of its time. Cousin to the dread-filled cosmic horror of Lovecraftian fiction, with more than a dash of McCarthyism paranoia about "the other," it presaged entire generations of genre-defying speculative fiction, including series such as Black Mirror. During its original, five-year run, writer and creator Rod Serling took people on an anthologized journey of unnerving, uncanny morality tales that often focused on universal themes such as humanity's folly, vanity, ignorance, and arrogance.

Stories such as "Time Enough at Last" stand out in memory (where a man surrounded by books loses his glasses), as does "Eye of the Beholder," where a women's facial reconstructive surgery leaves her "ugly" to a society of pig-looking people (per Thrilllist). Other, military-themed episodes such as "A Quality of Mercy," "The Purple Testament," and "In Praise of Pip" reveal Serling's past and the origins of the series itself.

Crafted from war-time scars and trauma

Before creating The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling worked on numerous TV shows in the early 1950s that led to his rise to prominence, as Britannica explains. He quickly became a prolific and respected writer, garnering two Emmys (1955's Patterns and 1957's Requiem for a Heavyweight) and selling 90 scripts as a freelancer. Eventually, though, Serling became tired of the constraints and sanitization of network television under CBS, especially because he wanted to focus on "controversial" topics like race relations and labor unions. So, he decided to shift his ideas to a playground where such things were permissible — sci-fi — and wrote, produced, and of course narrated, The Twilight Zone. In The Vintage News Serling's daughter quoted him as saying, "An alien can say what a Republican or Democrat couldn't."

And what better venue to explore warfare and the human predilection for self-destruction? For Serling, this was a very personal topic, as he had served in World War II before turning to writing. In the 511th's demolition platoon, Serling's squad leader said that the future writer "didn't have the wits or aggressiveness required for combat," despite Serling's temper and former training as a boxer, as Military states. By the time Serling was discharged, however, he had earned the Purple Heart, Bronze Star, and Philippine Liberation Medal. Along with these honors, Serling took his trauma home with him, as well as a lifetime of PTSD-wrought nightmares and flashbacks.

Inspired by a death senseless even among the senselessness of war

Rod Serling's wartime service proved to be a fundamental source of his writing, which we can see in The Twilight Zone, where characters invariably try to make sense of a senseless, freakish world. Writing was, for him, a method of inviting social discussion and an act of self-therapy. As Serling said, "I was bitter about everything and at loose ends when I got out of the service. I think I turned to writing to get it off my chest."

One event, though, left Serling stricken above all others. It was an event so surreal and bizarre as to be perfectly suited for one of his scripts, and it happened during Serling's first deployment at the Battle of Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. From October 23 to 26, 1944, as Britannica recounts, combat raged on the island of Leyte, largely considered a hopeless suicide mission, but it wasn't the combat itself that left Serling broken.

The National World War II Museum describes how, during downtime between bullets and bombs, Serling's friend, Private Melvin Levy, decided to watch the Air Force's ammunition drops come in. Serling and Levy were joking about where the drops would land when a crate fell from the sky and decapitated Levy. This freak accident shocked Serling, and he took the wound home with him along with two physical injuries. One of them, in the knee, would plague Rod Serling his entire life as surely as the memory of his friend.