What Happened To The Bodies At Okinawa?

It's very easy to depersonalize death, especially when it comes to war. One lost life is a tragedy, and 10,000 are a statistic. Even words like "victim" or "casualty" turn a person into an abstraction, or a role, rather than a soul with a family, life, hopes, fears, and loves no different from one's own. So when talking about warfare and soldiers, battles and victories, or big historical events in general, it's important to remember that we're talking about real individuals, not faceless concepts.

World War II, for instance, saw around 60 million people lose their lives, both military and civilian across dozens of countries worldwide. To put things in perspective, that's about one in five people living in the United States in 2024, or half the population of Japan, or almost four times the entire population of the Netherlands, all of which endured the war. The famed Battle of Normandy in 1944 cost over 200,000 lives. The Battle of Stalingrad between Germany and Russia caused an unbelievable 2 million deaths, the highest count of the war. And the Battle of Okinawa — fought between the United States and Japan in 1945 — resulted in over 12,000 American deaths, and up to 220,000 combined Japanese soldier and civilian deaths.

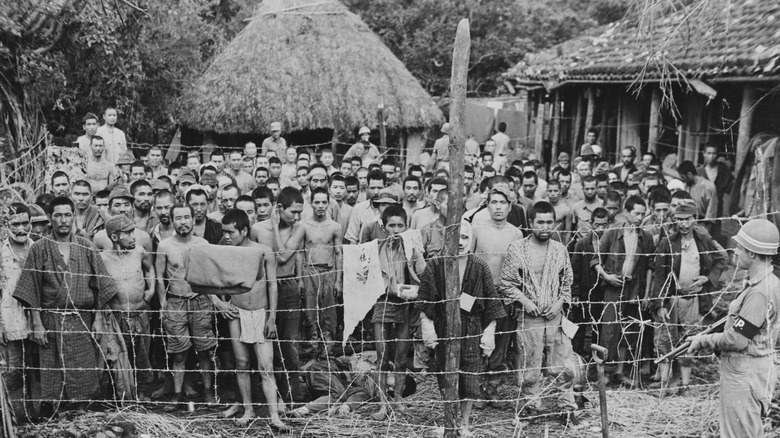

It was the largest amphibious assault of World War II. Some of the dead were buried right then, and some were left where they fell and are still being found today.

A hard-fought, bloody battle

The Battle of Okinawa was the last major conflict of World War II and finished a mere two months before the U.S. dropped the atomic bombs Little Boy and Fat Man on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively. Germany surrendered in May 1945, right in the middle of Okinawa, which lasted from April to June that year. Essentially, Okinawa was the conventional combat capstone to both the war in Pacific and the war as a whole.

But Okinawa was particularly brutal. Japanese soldiers proved savage defenders more than willing to die, even via suicide, to win. Kamikaze rockets, torpedoes, ships, and planes bombarded U.S. vessels. The scene on land, smothered in rain and artillery, was "nothing but mud; shellfire, flooded craters with their silent, pathetic, rotting occupants; knocked-out tanks and amtracs, and discarded equipment — utter desolation," wrote marine Eugene Sledge in his book "With the Old Breed, at Peleliu and Okinawa." Nearly a quarter of a million Japanese soldiers and civilians died over 83 days, and the U.S. suffered one of the costliest battles in its country's history.

In fact, the fighting was so vicious on Okinawa that it left President Truman "rattled," as Joseph Wheelan writes in his book, "Bloody Okinawa: The Last Great Battle of World War II" (per Smithsonian Magazine). "They could see how costly it would be to invade the mainland," Wheelan wrote, "... The island would just be a charred cinder." Okinawa, plus Iwo Jima before it, directly influenced the decision to drop atomic bombs on Japan rather than go through more troop-on-troop battles.

U.S. troops were buried at temporary cemeteries

For U.S. soldiers slogging through Okinawan rain, heat, bullets, and explosions, death was everywhere. Battlefields were full of the "residue" of battle, as one 77th Infantry Division soldier once wrote, including "the bodies of their [Japanese] soldiers, their children, lying torn asunder," per the National WWII Museum. Ghastly as it sounds, front lines were close enough for the living to head out every single day, retrieve what remains they could, and bring them back. These remains were buried at temporary cemeteries further away from combat areas. There were six such cemeteries in total across Okinawa.

After Japan officially surrendered on September 2, 1945, the United States Department of War set about retrieving the soldiers who'd been buried at Okinawa's temporary cemeteries. In total, authorities recovered 10,243 such individuals and sent their remains to Saipan north of Guam in the Pacific Ocean. At that point, next of kin determined whether they wanted the remains sent back to the U.S., or interred at a military cemetery overseas.

Official death tolls for U.S. troops from Okinawa reached about 12,500 — 7,500 marines and 5,000 sailors. Given the number of bodies recovered, this means that over 2,000 soldiers never made it to the U.S.' temporary cemeteries at all. And since the U.S. originally deployed a staggering 184,000 troops to Okinawa to begin with, this also means that a full 7% of U.S. soldiers on the islands never went home.

Okinawan civilians were left where they fell

The Battle of Okinawa might have been the final major battle of World War II, but it was the first and last battle of the war fought within Japan's national borders. Okinawa itself had only recently been absorbed into Japan in 1875 during Japan's Meiji Era (1868 to 1912). Before then, Okinawans were their own people and their own, mixed ethnic group in their own kingdom — the Ryukyu Kingdom — for over 400 years. And when the U.S. attacked Okinawa, all of its history and civilians got caught in the crossfire.

Many more Okinawan civilians died during the Battle of Okinawa than Japanese soldiers — up to 150,000 civilians vs. more than 70,000 soldiers. Locals could do nothing but flee south through active battlefields until there was nowhere left to run. "We saw dead bodies," PBS quotes survivor Shige Nakahodo, "crying and screaming people, and a person who was begging to be shot to death. It was total chaos."

Japanese soldiers fell to the ground as locals fled to caves. Fearing being tortured or murdered by Americans, some locals died by suicide. And yet, it fell to these same locals to gather the dead after the war ended. They built monuments around Okinawa as they burned the deceased until the Japanese government intervened in 1955. Uncollected remains were gathered together in Naha, Okinawa's capital, but its ossuary proved too small. The bones were then moved to Itoman, south of Naha, where they remain as part of a memorial complex. Despite cleanup efforts, about 2,800 people Japanese people remain lost to this day.

Mutilating and disgracing the dead

Not all of those who died during the Battle of Okinawa were moved to temporary cemeteries on the U.S. side, or collected and burned on the Japanese side. Numerous sources provide glimpses into the worst possible outcome for many of the deceased on both sides, particularly those Japanese mutilated and dismembered by American soldiers after death. As an article on the Journal of Military Ethics writes, we're talking about war crimes — and this doesn't even take into account the rampant rape and burning alive of Okinawan civilians by American troops.

Teeth, skulls, and ears were the U.S. military's most commonly collected form of "war trophies" and were carried around and put on display. U.S. media described Japanese people as "yellow vermin" and "living, snarling rats," as Rare Historical Photos cites. According to a piece in The Pacific Historical Review, "abuse of [Japanese] remains carried with it no moral stigma." Life Magazine's May 22, 1944 picture of the week featured a young U.S. woman gazing at a Japanese skull on her desk sent to her by her Navy boyfriend because he had "promised her a J**," as Rare Historical Photos also cites. This shows that war trophies collected at Okinawa were not the first of their kind.

Other dead, as the South China Morning Post describes, weren't left where they'd fallen. Survivor Kiyoshi Uehara, for instance, describes one Okinawan mother and father refusing to leave the corpse of their 7-year-old daughter behind. They tied her to their own bodies and carried her around for days.

Recovering those left behind

As described above, many of the dead who fell at Okinawa — on both U.S. and Japanese sides — are still there. Remains continue to be found to this day, largely thanks to active search efforts. 2021 saw eight individuals found in a cave in Okinawa's south. An Okinawan official said on The Asahi Shimbun, "In the past seven to eight years, the remains of one to three people are typically found at a single location. Finding more than five remains is unusual." And yet, more recently in 2023 the remains of 46 women and one child were discovered together.

The non-profit Kuentai-USA, a joint Japanese-American venture, remains devoted to uncovering and repatriating those still unaccounted for in Okinawa and other Pacific islands. Formed in 2014, they've found 16,000 soldiers in the Philippines, 800 in Saipan, and have turned their attention to Okinawa. The organization even has a giant list of named, still-missing U.S. servicemen. At the same time, in 2021 the Japanese Ministry of Defense announced a plan to build a new U.S. military base on Okinawan soil where people are still digging for World War II's remains. As of 2021 public protest halted the plans for the time being, although the clock is ticking. Even if new construction didn't threaten the remains of those dead and left, these remains are still almost 80 years old and decomposing. As Kuentai-USA says, "If the remains are not repatriated sooner, there would be nothing to identify when the remains are all disappeared."