The Bombings Of Hiroshima And Nagasaki Were Worse Than You Thought

By 1945, World War II had been dragging on for years. Even worse, there was no end in sight — Japan had sworn they would fight to the last man standing. Casualties continued to rise, and according to History, General Douglas MacArthur and other Allied leaders were looking at a plan that involved more bombing, a large-scale invasion, and estimated casualties of another million.

There was no course of action that wasn't extreme, and it was US President Harry Truman who decided to use the newly developed weapons that would — he hoped — put America front and center when it came to deciding the outcome of the war.

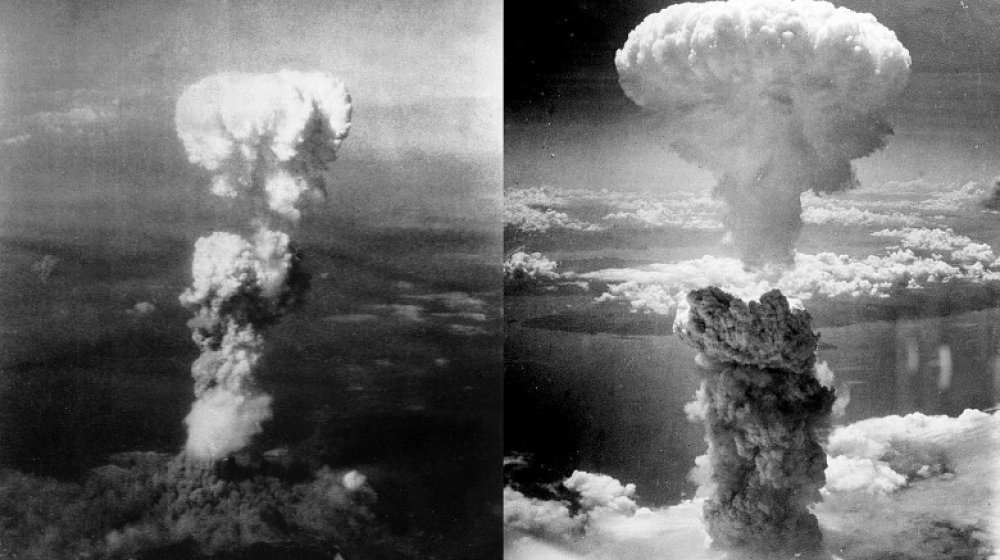

The first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, destroying 90 percent of the city and instantly killing 80,000 people. Three days later, another bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, killing another 40,000. Tens of thousands would die in the following months and years because of radiation sickness, and on August 15, Japan surrendered. Those are terrible numbers, but that's just the beginning.

The sight of Hiroshima from the Enola Gay was horrifying

The first atomic bomb was dropped by an 11-member crew of a B-29 bomber called the "Enola Gay," named for the mother of pilot Col. Paul Tibbets. According to navigator Theodore Van Kirk (via The Guardian), "You couldn't be in the 509th and not know something was up. [...] They told us that the weapon we were going to drop would destroy an entire city." Words like "atomic" never came up.

The Enola Gay's tail gunner was then-Tech Sgt. George Robert Caron, and he used the camera he'd been given to take photos of the explosion, and document what he saw. His recollections (via Business Insider) are chilling. "[The mushroom cloud] was white on the outside and it was sort of a purplish black towards the interior, and it had a fiery red core, and it just kept boiling up. [...] I could see the city [...] and it was being covered with this low, bubbling mass. It looks like bubbling molasses, let's say, spreading out and running up into the foothills, just covering the whole city."

That's when they turned around so everyone else could see what was going on. That, too, is when copilot Robert A. Lewis wrote on the back of an old War Department form: "I honestly have the feeling of groping for words to explain this or I might say, my God, what have we done?"

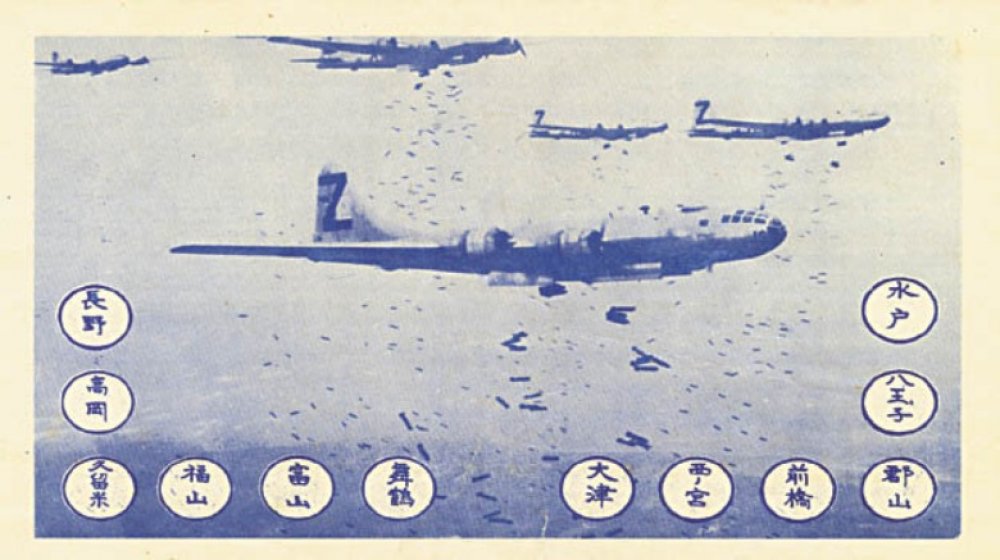

There were warning leaflets, but most people didn't see them

Before Allied bombers actually bombed cities, they would drop something else — warning leaflets. According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, it was common practice throughout the war, and it was done before — at least — the bombing of Hiroshima. The leaflets were more properly called LeMay Leaflets, and warned civilians that they lived in a city with military or industrial targets, and they should absolutely get out of town before the imminent firestorm. It's unclear how many leaflets were dropped, and the historical record is iffy on the details. However, one survivor interviewed by Time had a distinct memory of them.

Sachiko Matsuo survived Nagasaki and was just 1.3 km from the hypocenter when the bomb hit. She said: "American B-29 bombers dropped leaflets all over the city, warning us that Nagasaki would 'fall to ashes' on August 8. The leaflets were confiscated immediately by the kenpei (Imperial Japanese Army). My father somehow got a hold of one, and believed what it said. He built us a little barrack up along the Iwayasan (mountain) to hide out in.

The 8th came and went, and in spite of protests from some in her family, they stayed one more day — after her father reminded them, "The US is a day behind, remember?" Had more leaflets made their way into the hands of citizens like her father, the final death toll may have looked different.

The initial blast was just the beginning

It's the mushroom cloud that's perhaps the most popular images of the immediate consequences of the bomb, but those who were on the ground say it was just one part of it. Shinji Mikamo's stories — compiled by his daughter, Aikko, and shared by the BBC — told of things much more horrifying. "Suddenly, I was facing a gigantic fireball. It was at least five times bigger and 10 times brighter than the sun. It was hurtling directly towards me, a powerful flame that was a remarkable pale yellow, almost the color of white."

Then there was the noise, and the sensation that he had been doused with boiling water. He found himself buried in the rubble of his house, saved by his father, Fukuichi, and when they finally started walking through the remains of their city, he described storm-force winds that swept through the rubble. That photo? That's not the Hiroshima bomb, that's the firestorm cloud that followed hours later.

And then, CNN says, it started to rain. It wasn't the sort of rain that could extinguish the fiery tornadoes, though, it was the sort of rain that was black and radioactive. It was sticky, too, and even when people finally had the chance to try to wash it from their blistered and burned bodies, they couldn't.

More people survived both explosions than you might think

History estimates that somewhere around 260,000 people survived the atomic bombs, between both Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Some — like Tsutomu Yamaguchi (pictured) — survived them both. He was 29 in 1945, and an employee of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. Just a few miles from the bomb's hypocenter, he was badly burned and his eardrums ruptured. He found a few other survivors, spent the night in an air raid shelter and the next day, he headed to the train station. After swimming through a river clogged with the dead, he got on a train... and headed home to Nagasaki.

He was treated by a doctor — a former classmate who didn't recognize him beneath the burns — and shockingly, he headed to work on August 9. He was in the middle of briefing the company director on the events of Hiroshima when the second bomb hit. His family, too, survived, as his wife had gone out to buy burn cream for him and hadn't been at their home when it was turned to rubble.

Perhaps most surprisingly, he wasn't alone. It's thought that around 165 people survived both the bombing at Hiroshima and at Nagasaki, and they're called the "nijyuu hibakusha," which means "the twice-bombed person."

Aftermath: Shinji Mikamo

It was a hot and humid day, Shinji Mikamo remembered (via the BBC), and after the bomb dropped, he was pulled from the remains of his home by his father, Fukuichi. Shinji was badly burned: "My skin hung off my body in pieces like ragged clothes," he remembered. He could see the flesh underneath, and it was a bizarre yellow color that reminded him of a particular cake his mother liked to make.

After they collected themselves, they headed off to search for shelter. What they saw as they walked through the ruins that had once been their home, then across a bridge... it was horrific. Shinji remembered: "My feet were charred and clumsy. Every step or so, I would unintentionally hit an arm or a leg and hear the person below me wince in pain. I felt like a vulture. Crossing that bridge, and leaving all those wounded people behind to die."

They grew weaker and weaker, finally able to do nothing but crawl. Fukuichi ignored his son's pleas — he just wanted to die — and they kept going. Even as the cold cruelty of some made Fukuichi say, "We are in hell right now. No wonder we see demons," others were kind. Eventually, they were separated, and Shinji alone was evacuated by the army — when he was strong enough he went searching for his father, but never found out what happened to him.

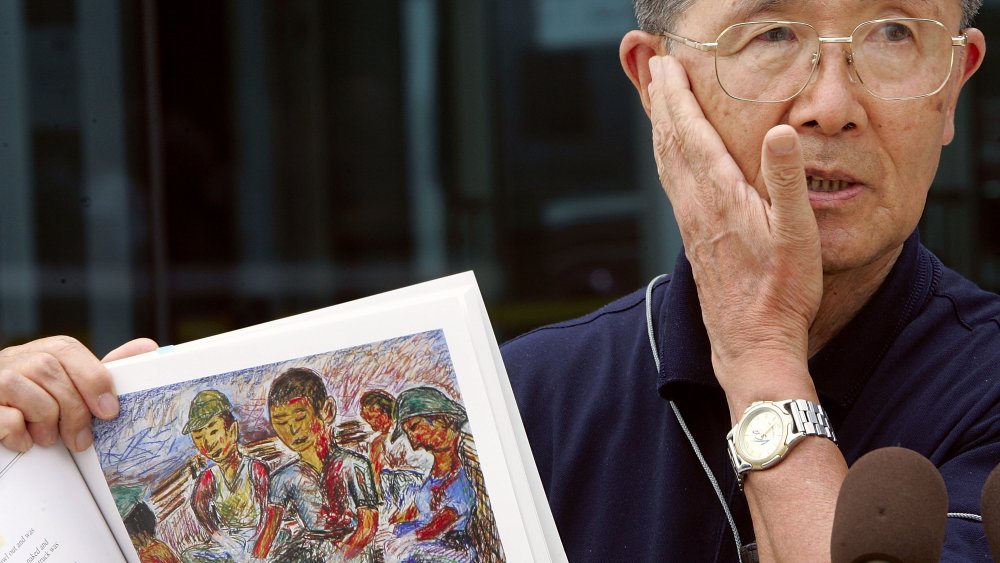

There was no pain: Sumiteru Taniguchi

Sumiteru Taniguchi (pictured, left) was 16 when the bomb hit Nagasaki, and he had been out delivering mail when he was thrown off his bike (via The Washington Post). His injuries were unthinkable: "The skin of my left arm, from the shoulder to the tip of my fingers, was dripping like rags. I put my hand to my back, but there was no clothing. I could feel something slimy. [...] I didn't feel any pain and there was no blood. But all my energy seemed to vanish." It was days before he was taken to a Japanese military hospital; months later, the US Strategic Bombing Survey filmed him being treated. The footage was so terrible it was buried for decades.

When Susan Southard recorded his story for her book Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War, she wrote (via National Geographic) that he spent three years laying on his stomach as his back healed. It was years of agony — bedsores developed so deep that doctors could see his heart beating in his chest.

He was released in 1949, and went on to speak publicly about the importance of nonproliferation of nuclear arms. When he appeared in front of the UN in 2010, he showed them a graphic photo of his injuries, saying, "I am not a guinea pig, nor am I an exhibit. But you who are here today, please don't turn your eyes away from me. Please look at me again." He died in 2017, at 88-years-old.

Left to dispose of the dead: Yoshiro Yamawaki

Survivors weren't just left to try to figure out how to continue to survive, they searched for their loved ones, too. Sometimes they found them, and sometimes, they were left alone to try to properly, respectfully dispose of their remains. Yoshiro Yamawaki and his twin brother survived the bombing of Nagasaki, and when they went to try to find their father, what they found instead was, in his own words (via the South China Morning Post), "our father's corpse, swollen and scorched. [...] To this day, I will never forget the moment I saw my father's remains, no matter how hard I try. I pray that no one should ever have to experience what I did at the age of 11."

The brothers knew that it was up to them to make sure their father was laid to rest, and they attempted to cremate him. When they returned the next morning, though, intending on collecting his ashes, they found (via Time): "Only his wrists, ankles, and part of his gut were burnt properly. The rest of his body lay raw and decomposed."

Now wanting to leave him, it was an older brother that suggested they observe a Japanese funerary tradition where they took a piece of his skull. "[...] however, the skull cracked open like plaster and his half-cremated brain spilled out. My brothers and I screamed and ran away, leaving our father behind. We abandoned him, in the worst state possible."

Water... please

Testimonies are filled with descriptions of burn victims pleading for water, and some — like Inosuke Hayasaki — stopped to help them. He recalled (via Time): "I decided to look for a water source. Luckily, I found a futon nearby engulfed in flames. I tore a piece of it off, dipped it in the rice paddy nearby, and wrang it over the burn victims' mouths. There were about 40 of them. I went back and forth [...] Among them was my dear friend Yamada. [...] I placed my hand on his chest. His skin slid right off, exposing his flesh. I was mortified. 'Water...' he murmured. I wrang the water over his mouth. Five minutes later, he was dead."

After the bombing, it didn't take long for warnings to be passed by word-of-mouth. Survivors were told not to drink water, or give other victims water, because it would kill those who were begging for a drink. According to Dr. Hiroo Dohy of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital (via Peace Seeds), that was because drinking water could increase blood flow. For wounded burn victims, that was potentially deadly.

For those like Inosuke Hayasaki — those who tried to help the other victims — that's left lingering doubts. "I cannot help but think that I killed those burn victims. What if I hadn't given them water? Would many of them have lived? I think about this every day."

There were so many orphans... the yakuza saw potential

According to Newsweek, around 2,000 children had been evacuated from Hiroshima ahead of the bombing. Evacuees were of a specific age group — 6- to 11-years-old — and when they returned, most realized very quickly that they were orphans. Some died within months of returning to the ruined city. According to one — Shoso Kawamoto — some were so hungry "they died with stones in their mouths." That was in spite of the efforts of some locals, who set up stalls the orphaned children could visit for food. But there wasn't enough food to go around, and the smaller, younger children were left with whatever scraps they could find.

Kawamoto, says DPA International, was one of the lucky ones. He found a home with a foster family, but many weren't nearly as fortunate. After the bombing, Kawamoto says that he saw many of the young orphan girls sold the the Yakuza, where they were forced into a life of prostitution.

The Yakuza saw an opportunity, and he says they moved into Hiroshima in the wake of the bomb. Orphans less fortunate than he was had two choices: starve, or work for the Yakuza — and many did what they needed to in order to survive.

Survivors of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki faced incredible discrimination

Those who survived the dropping of the atomic bombs are called hibakusha — and for a long time, they faced almost unthinkable discrimination. Take Hiroko Tanaka. She survived Hiroshima, but when it came time for her to apply for official government status as a hibakusha, she waited five decades. (Holding an official hibakusha designation comes with certain important benefits, like access to government subsidies for health care, says The Japan Times.) Her husband explains why she waited (via The Independent): "She kept her status hidden from me. At the time, there were all sorts of rumors. People in Tokyo said, 'Don't marry someone from Hiroshima, you will be contaminated.'"

Many hibakusha have similar stories. When Nagasaki survivor Katsuko Kanamori left the remains of her home and moved to Gifu, she quickly learned to make up stories about her past. The Japan Times says that when it came to everything from seeking employment to marriage, no one wanted a hibakusha — they were afraid the radiation was contagious.

Shoso Kawamoto found that out in one of the most heartbreaking ways possible (via The Conversation). He was 23 when he met and fell in love with a girl he wanted to marry, but he held a hibakusha designation. His fiancee's family forbid the marriage — devastated, he left the city, and vowed never to marry.

Censorship and secrecy delayed treatment for survivors

When the bombs were dropped, little was known about what the consequences would be for survivors. According to research done by Claremont Graduate University Professor of History Janet Farrell Brodie (via The Conversation), censorship by occupying US forces made things even more difficult for those trying to treat survivors.

Brodie says that while the US publicized information about the bombs' destructive power, they kept other things — like the effects of radiation — quiet. She found that even as medical personnel struggled to treat patients and document illnesses, officials seized everything from medical case notes to biopsy slides, photographs, and film. That information — information that may have been useful if it was shared among the medical community — was then sent back to the States, where it was classified. They even went as far as restricting any criticism of American activities in Japan, and completely denied there were any lasting effects from the radiation.

Some survivors waited a long time for help. Do-oh Mineko survived Nagasaki, and by 1949, her injuries were still unhealed, and her hair still fell out as soon as it grew in. That was when the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission showed up on her doorstep (via Politico) and promised to help. She was taken to a US facility, photographed, and sent home. The ABCC was operating with strict orders not to provide medical treatment, only document for further study. She was so ashamed of her injuries, she remained a shut-in for years.

No... the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki didn't end the war

We've heard again and again that the dropping of the atomic bombs is what led to Japan's surrender, but some historians say it's just not true. According to Gregg Herken, emeritus professor of US diplomatic history for the University of California (via The Washington Post), new research into Japanese records show it's more complicated than that. On August 8, the Soviet Union entered the war against Japan. They'd previously honored a nonaggression pact with the country, and Japan still hoped the Soviets would act as something of an intermediary between themselves and the Allies. With a Soviet attack, though, things changed... and Japan surrendered.

The Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs points out that yes, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the proving ground for atomic weapons, but the US had actually bombed 68 Japanese cities in 1945. When it comes to casualties, Hiroshima is second. Compare that to the March 10, 1945 bombing of Tokyo, when bombers dropped cluster bombs and napalm on the city. Around 105,400 people were killed, and a fifth of the city was reduced to ruin (via The Tampa Bay Times). At the end of the day, atomic bombs were just more bombs, while the Soviet Union's entry into the fray was different. The Carnegie Council puts it this way: "The Soviet declaration of war was decisive; Hiroshima was not."

Have decades of historians been wrong? Was it really all unnecessary?