What Happened To The Bodies From Iwo Jima?

Even those who don't know Iwo Jima by name will likely recognize the battle's Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of U.S. troops raising a flag on a hilltop. The image, while captivating, doesn't even begin to tell the story of the Battle of Iwo Jima and those who died there. Other World War II battles might have been deadlier, like the Battle of Stalingrad when 2 million people died. Other battles might stand out more in memory, like the Battle of Normandy. But Iwo Jima stands out not just for its iconic photo, but because of the ultimate senselessness of the conflict.

Unlike the subsequent Battle of Okinawa, a savage battle where far more civilians died than soldiers, Iwo Jima pit soldier against soldier — Japanese vs. American. About 70,000 marines made an amphibious landing on the tiny island and faced off against about 21,000 members of the Japanese imperial army. In the end, about 7,000 U.S. men died and 25,000 were wounded. On the Japanese side, only about 200 men survived. While records often use euphemisms like "casualties" to describe such people, it's important to note that we're talking individuals no different from anyone alive today.

Ultimately, those U.S. troops who fell were interred at temporary cemeteries before being exhumed later and sent to their final resting places — those who could be collected and identified, that is. Japanese troops suffered a much harsher fate. While some were placed in temporary cemeteries like their American counterparts, many are still missing on Iwo Jima to this day.

Savage fighting on 'Sulfur Island'

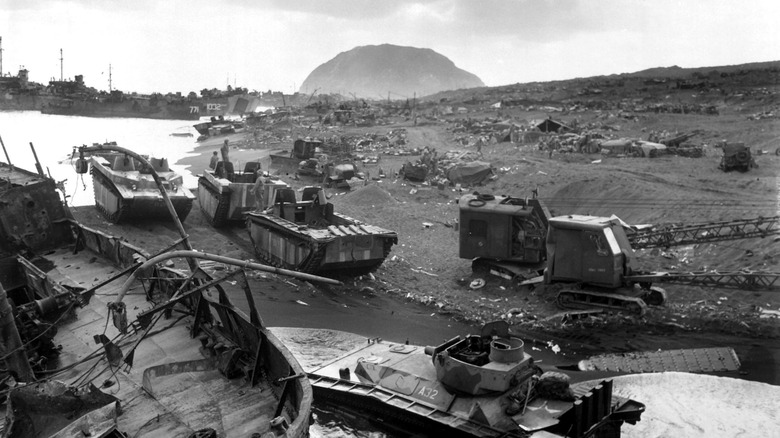

On foot, the tiny speck of Iwo Jima — aka "Sulfur Island," located about 750 miles south of Tokyo, Japan in the Pacific Ocean — would take only about two hours to walk across. But for the American troops who landed on the island, it cost them about 800 lives per square mile across a messy bed of soft, shifting sand and volcanic ash. Starting on February 19, 1945 and ending March 26, combat was ruthless and bloody. U.S. Army and Navy officials believed that it was worth it, thinking Iwo Jima would make a good staging point for the Pacific. In the end, the island was used for nothing more than emergency airfields.

When American troops landed on Iwo Jima, Japanese General Tadamichi Kuribayashi decided against meeting the U.S.' "storm landing" head-on. Rather, he opted for a guerilla strategy and receded into the island's inner recesses and caves. This is partially why the fighting on Iwo Jima was so difficult, and why the Japanese troops were killed almost to a man. On top of this, bombers shelled the island for three days before any marine ever stepped foot on it.

The brutality of the fighting on Iwo Jima, plus the subsequent viciousness during the prolonged Battle of Okinawa — which saw almost a quarter-of-a-million soldiers and civilians killed — was a big part of why U.S. President Truman opted for dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, rather than engage in conventional land battles.

U.S. marines were interred in temporary cemeteries

Even after a three-day-long naval bombardment, Iwo Jima wasn't easy for U.S. marines to take. Japanese troops saturated beaches with artillery shells and machine gun fire even as U.S. troops, vehicles, and supplies sunk into the island's soft surface. Some marines were injured and taken out of combat back to ships. Some died and their bodies were retrieved. Some were just gone. As veteran Dick Verner describes on the D. Clarke Evans Photography website, he once saw dead stacked "five high maybe 100 yards long."

Those marines who could be collected were buried in one of three temporary cemeteries split up by marine division. Photos from the time show the 3rd and 4th Division marines interred in organized, neat rows with headstones marked by numbers. Other photos show servicemen walking around such cemeteries even as combat raged in the distance. Yet other photos show a stone enclosure and arched entryway around the 5th Marine Division cemetery — we've even got rare footage of the opening ceremony for this cemetery (above). All such individuals were eventually repatriated to various places in the U.S., like Arlington National Cemetery.

Not all of those who died and were recovered went to these temporary cemeteries, however. Some were buried at sea in a standing, "parade rest" position. Some, like the photographer who took the iconic flag-raising photo, are still thought missing on the island, perhaps in one of its many caves.

Japanese soldiers were lost or buried in caves

As bad it was on Iwo Jima for U.S. Marines, Japanese soldiers faced even more horrifying circumstances, and their bodies suffered even worse fates. As mentioned, many Japanese soldiers retreated into Iwo Jima's interior, often into its caves. Those caves wound up being traps as U.S. soldiers came through with flamethrowers spewing fire into cave mouths, thereby burning those inside to death or asphyxiating them as the fire consumed all the cave's oxygen. Or, they used explosives to detonate cave entrances and bury those inside alive. Such caves, for all intents and purposes, wound up being mass graves, even to this day.

Those Japanese soldiers who could be identified and collected, however, were placed in temporary graves around Iwo Jima much like the U.S. did their own troops. When marines stumbled across these locations they referred to them as "enemy cemeteries." The task of rounding up deceased Japanese soldiers gets more difficult considering just how many soldiers died by suicide. Many corpses are headless, as their owners followed precepts laid out by Japan's World War II General Hideki Tojo. "Live and suffer not the humiliation of being a prisoner of war," the phrase went. Rather than be captured, many soldiers simply put a grenade to their head and pulled the pile. The bones of such individuals, as well as those who died in caves or otherwise have never been identified, amounted to a staggering 12,000 Japanese troops — more than half of their entire force.

Ongoing recovery efforts of the dead

The search for the bodies of the remaining Japanese soldiers on Iwo Jima is ongoing, albeit slow and piecemeal. Recovery efforts didn't begin in earnest until 1968, when control of Iwo Jima passed back to Japan from the U.S. By then trenches had filled up and Iwo Jima's jungles had gotten overgrown. Nonetheless, author Sohei Sakai on Kodansha asks why there isn't more of a concerted effort to collect and put the bones of the dead on Iwo Jima to final rest and blames lackluster efforts on the part of the Japanese government.

The Japanese government conducted radar searches from 2012 to 2013, and then excavations from 2014 to 2017 of 1,800 potential locations, with limited success. One of the most promising recovery zones — under Iwo Jima's airstrip — remains untouched. Other recovery efforts are spearheaded by relatives or friends of the deceased, many of whom are elderly and require help.

And yet, bones have cropped up over the years. Most notably, two mass graves were discovered in 2010 containing up to 2,000 of the 12,000 total unrecovered soldiers. "Many of the remains were little more than grains of sand," dig site supervisor Kazuo Takenoshita said on NBC News. "They were often piled two to three deep. One soldier's head would be resting on another's feet."

Memorializing the dead

Taken all in all, those deceased soldiers — either U.S. or Japanese — who made it back to their home countries could be counted among the lucky. While we don't know precisely which cemeteries this or that soldier went to, we know that final resting places are a matter discussed between militaries and the loved ones of the deceased. Some military cemeteries like Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia don't charge fees for internment of the dead, which could prove very helpful for family members. Arlington would also prove a fitting resting place because it contains the Iwo Jima Memorial, a statue of the famed flag-raising photo we discussed earlier (above).

And yet, many U.S. marines take the entirety of war-torn Iwo Jima to be a WWII memorial. As the U.S. Naval Institute says, "The entire island is a shrine." The wreckage of the battle remains everywhere on the island, from decayed ammunition to entire tanks, mess kits to lost ships off shore. Marines treat the island like a kind of pilgrimage site, or even holy site, to honor the dead on both sides. On the United States Marine Corps official site, Lt. Evan C. Clark described American and Japanese veterans from the conflict meeting on Iwo Jima 40 years after the battle ended. They "came together in friendship to honor the sacrifices of those who fought bravely and honorably," and a plaque was raised in honor of the event. We can only hope that such gestures are enough for those who still remain on Iwo Jima.