Here's Why People Keep Dying On Mount Everest

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

It was once the holy grail of mountaineering: Conquering Mount Everest, that lonely mountain top nestled among the stars, where few human beings have dared to go. Today, it's like standing in line to ride the Matterhorn at Disneyland, only you could die.

Climbing to the top is no longer an accomplishment for just peak athletes who train for years before facing the greatest physical challenge of their lives. Now, people who sign up to climb the world's tallest peak do it mostly so they can brag about how they climbed the world's tallest peak. There is no physical fitness requirement, just a financial fitness requirement. And it isn't any less dangerous than it was back in 1953, when Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay became the first confirmed climbers to reach the summit. (We don't know if two other climbers who vanished while trying to reach the summit in 1924 actually made it or not.)

Climbing Mount Everest is so dangerous that one stretch on the north side is called "rainbow ridge," not because it's all cheerful and unicorn-y but because all the dead bodies are wearing brightly colored climbing gear. And yet people still climb the mountain, because no one ever thinks it will happen to them. So why so many bodies? Everest climbers have died from varied causes, but here are the most common, and why there have been a few spikes.

It isn't just falling

Mount Everest is more than 29,000 feet tall. Knowing that, you might be tempted to believe that the major cause of death on the mountain is falling, but alas, that's only the second most common cause of death. Most people who die on Everest are killed in avalanches. The third most common cause of death on the mountain is exposure or frostbite, which accounts for around 11% of fatalities, followed closely by "acute mountain sickness." Around 27% of Everest fatalities are listed as "other," which could include falling ice, rope accidents, pneumonia, and even drowning.

Also a bit counterintuitive is that more people die on the way down from the summit than on the way up. But route preparation is dangerous, too. A total of 120 people have died while working on the routes, with a handful more dying at base camp, en route to base camp, or during an evacuation. Indeed, you're not safe anywhere on Mount Everest.

Traffic jams

Mount Everest is one of the most remote places on Earth. It's also one of the world's greatest physical challenges: It takes 10 days just to get to base camp in Nepal, six weeks to acclimatize, and another nine days to climb to the top. It's also expensive, with the bottom-dollar figure for a Mount Everest expedition being about $30,000, with an average cost of around $65,000. And yet one of the things that's been killing people on Mount Everest is something most of us wouldn't expect: foot traffic.

Modern Everest is a tourist trap, and on a perfect climbing day, you might encounter hundreds of other climbers, all of whom are trying to get to the exact same spot. So, you have to wait in line. Yes, much like your favorite theme park, Everest has a queue. The difference is, if you stand too long in line at a theme park, the only pain and suffering you'll experience is the endless whining of your children. If you wait too long in line at Mount Everest, you might run out of oxygen and die.

Inexperienced rich people

You can climb Everest from two different base camps: One is located in Nepal, while the other is in Tibet and operated by China, and both nations used to be pretty selective about who got to go up the mountain. In fact, up until 1985, Nepal allowed only one expedition on each route at a time. But Nepal is not a wealthy nation, and a single climbing permit costs $11,000. That represents a significant income for Nepal; in total, the climbing industry is worth about $300 million a year. The Nepalese government issued 381 permits in 2019 (a record number), and had no intention of scaling back that year despite the highest death toll since 2015.

The problem isn't just the number of permits Nepal is issuing, it's who they're issuing those permits to. There are no officially designated physical requirements and no tests you need to pass in order to qualify, so some of the adventure outfits operating in Nepal are less-than-selective about who they'll take to the summit. These are cost-cutting operations, the sort of companies you might turn to if it's always been your dream to climb Mount Everest, but you're only sort of wealthy and/or you're not in especially good shape.

That means more inexperienced climbers on the mountain, which means more danger for everyone. Critics also say that Nepal has a reputation for corruption and lax safety regulations, which doesn't help either.

A tiny, tiny, window of opportunity

You might imagine the best time to visit Everest would be high summer, when you don't have to worry about blizzards and freezing temperatures. But nope, you can only really climb Everest during the month of May, because there's a very short window of time between the winter storm season and the summer monsoon season.

But hey, that's at least balmy spring, right? Also nope, since at base camp, daytime temperatures max out at around 59 degrees Fahrenheit, and at night they drop to freezing. That temperature drops roughly 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit for every 490 feet of elevation, and the summit is 11,429 feet above base camp. (On the flipside, some parts of Everest can be hot in May, up to 90 degrees Fahrenheit, especially broad, snowy expanses that reflect the sun.)

So even in "ideal" conditions, the weather is going to suck. And just because you book your ascent during that narrow window doesn't necessarily mean you're going to be safe: In recent years, there have been a rash of what are called "blue sky" deaths on the summit of Mount Everest. Why? Because everyone wants to climb Everest when the sky is blue, and in the 2019 season, the weather window was especially narrow.

Once you reach 25,000 feet, you're already dying

No matter how hard you train or how physically fit you are, once you reach a certain elevation, you're dying, and you still have more than 4,000 feet to go. At that point, you're racing against your own mortality. "Once you get to about 25,000 feet, your body just can't metabolize the oxygen," Outside magazine editor Grayson Schaffer told NPR. "Your muscles start to break down. You start to have fluid that builds up around your lungs and your brain. Your brain starts to swell. You start to lose cognition."

That last 4,000 feet, in fact, is called "the death zone," because it's where a lot of climbers lose their lives due to heart attacks, strokes, and altitude sickness. Fluid can accumulate in the lungs, leading to altitude pulmonary edema, which causes a cough that's sometimes so severe it can crack a rib. The low oxygen levels can also lead to transient blindness or hemorrhage in the blood vessels of the eyes. And the whole experience is so physically taxing that one study found Everest climbers typically lose between 10 and 20 pounds. Even triathletes die there.

When you can barely help yourself, there's no way you can help others

Just to recap, when you reach the death zone, you're physically and mentally messed up. Hopefully, you're not so messed up that you can't finish the climb, and hopefully, you can get to the top and back down again before you become super extra-ultra messed up.

So that's okay, but everyone around you is also very much in the same situation as you, and some people do deteriorate to that state of super extra-ultra messed up. That leaves everyone on Everest with a difficult dilemma. Should you help someone who clearly won't survive without assistance, and in doing so jeopardize your own life? Or should you keep going, reach the summit, and hopefully live to brag about it? Because that's often what it comes down to: Help yourself and survive, or help others and maybe die along with them.

Once you're in the death zone, there's actually very little you can do to help a fellow climber in distress since you're unlikely to have the physical capacity to care for yourself and another person. It's not callousness that abandons people to die on Everest, it's just that abandoning people to die is often the only option.

Summit fever can kill you and others

It doesn't take a mountaineer to understand that impaired judgment and high altitudes are not a great combination. But add ego and a sticker price that's comparable to a brand new luxury SUV, and you've got all the ingredients for death and despair.

There is a phenomenon called "summit fever" that exerts a frighteningly fierce control over many Everest climbers. It is partially caused by impaired judgment, but it also has to do with fear of failure and "I just dropped $65,000 on this trip and I'll be darned if I'm not going all the way to the top" syndrome. People who have spent years preparing for Everest (or weeks bragging to their friends about how they're going to the summit, even though they can't be bothered to go to the gym) may not be ready to face defeat, even when it's obvious to everyone around them that they're not going to make it. People on Everest sometimes put the summit ahead of everything, including their own lives and the lives of others.

People who have summit fever can get so wrapped up in the quest to reach the top of the mountain that it becomes a part of their identity. That means they stop considering alternatives that don't align with that goal — alternatives like turning around when they run out of oxygen, or abandoning their push for the summit because they're just not physically capable of getting there.

Good old-fashioned falling to your death

Falls are common on Mount Everest, even for experienced climbers. In 2012, a Sherpa died after failing to clip his safety harness to one of the aluminum ladders that bridge large gaps in the ice, and in 2016, another Sherpa fell to his death while working on a route 500 feet below the summit. In 2017, Indian climber Ravi Kumar made it to the summit only to die after a 650-foot fall into a crevasse. So that's just a gentle reminder — no matter how skilled you are, no matter how far you've come, Everest might still get the last word.

Green Boots may have been a victim of summit fever

The most famous body on Mount Everest is called Green Boots, who most people believe was once a climber named Tsewang Paljor, although no positive identification was ever made. Green Boots got his nickname from the brightly colored pair of hiking boots he was wearing, which climbers had to step over on their way to the summit. For a long time, Green Boots served as an elevation marker, helping climbers know how far into the death zone they were and how much further they would have to go.

In 2014, someone moved Green Boots. It's still a mystery as to who did it and why, although it seems likely that the good Samaritan thought the guy should finally rest in peace rather than spending eternity as a landmark.

Green Boots, if he is indeed Tsewang Paljor, is an example of someone who may have succumbed to summit fever: Paljor pressed on to the summit despite being warned against it by his deputy team leader, who predicted bad weather. Paljor and his companion made it to the summit, but a blizzard struck during their descent, and they never made it back to camp.

David Sharp froze to death as more than 40 climbers passed him by

The most controversial death on Mount Everest was that of British mountaineer David Sharp, who was in fine physical condition and yet still succumbed to the elements. Sharp froze to death, and his death was particularly controversial because as many as 40 different climbers passed by without stopping to help.

The public reacted to Sharp's death with outrage, although many climbers defended the actions of the other people who were on the mountain that day. Incapacitated climbers in the death zone basically can't be rescued, and Sharp was already near death from severe frostbite. One of the climbers who received the brunt of the criticism was double amputee Mark Inglis, who was himself suffering from severe frostbite and had to be partially carried down the mountain by his Sherpas — and yet, the public was outraged that he hadn't stopped to help.

Sharp was climbing Everest solo, with insufficient oxygen, no Sherpa companions, and no radio. That didn't make him any less worthy of help, but it does explain why he was dying alone. Still, Sharp's death is seen by many as one of Everest's most shameful moments, an example of how in the death zone it's frequently every climber for himself.

Sergei Arsentiev died when he went back up the mountain after a successful climb

Francys Arsentiev wanted to be the first woman to climb to the summit without the use of supplemental oxygen. She did actually achieve her goal, but her condition deteriorated rapidly on the way down. At some point during the descent, she was separated from her husband, Sergei, who assumed she had gone on ahead of him. When Sergei got to camp, he realized that Francys wasn't there and immediately went back up the mountain with medicine and oxygen.

It is unlikely he ever found her. Francys was just four hours from the summit when two climbers found her near death and stopped to help, giving up their own bid for the peak. They were ultimately unable to save her, and they had to leave her to die. Sergei died, too. His body was found one year after his wife's death, and it looked like he'd fallen while trying to come to her aid.

Marco Siffredi died while snowboarding down Everest

Most people who die on Everest aren't being deliberately reckless. Abnormal behavior is usually due to poor judgment caused by the high altitudes and diminished oxygen levels they experience once they're inside the death zone. And then there was Marco Siffredi, who was actually being deliberately and unfathomably reckless, and died while snowboarding down Mount Everest.

Now you kind of have to admire the steel cahones that would compel someone to do this. The guy had actually already snowboarded down Everest, it just wasn't on the particular part of the mountain he'd been hoping to snowboard down because there wasn't enough snow there in May 2001. So he returned the following year in September, again summited the mountain, and off he went — never to be seen or heard from again. Later that day, Sherpas claimed to have seen a man snowboarding down the mountain, but when they investigated, they could not find any tracks.

There was a lot of fresh powder the day Siffredi disappeared, so the prevailing theory is that an avalanche killed him. His body was never recovered.

The high altitude causes confusion and potential brain damage

People at high altitudes risk developing High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE), an incompletely understood condition characterized by fatigue, confusion, and difficulty coordinating movements. Current theories blame either high blood pressure within the skull or cellular damage from low oxygen levels. Between 0.5% and 1% of people ascending over 4,000 meters will develop some degree of HACE; there are no patterns in age and sex, but epidemiologists note a greater risk among young men, who are more likely to keep climbing despite warning signs. Rapid ascent without sufficient adjustment periods and a history of HACE or altitude sickness are key risk factors.

Initially, HACE may be confused with exhaustion, low blood sugar, dehydration, or other common ailments. As it progresses, it shares some symptoms with mental illness, as patients become disoriented, have trouble speaking, and may struggle to remain awake. Early recognition is key, as HACE can lead to permanent brain damage, coma, and/or death within 24 hours. The primary treatment is cautious but rapid descent, preferably to under 1,000 meters above sea level.

The fourth woman to summit was the first woman to die there

In a world that has too often ceded leadership positions by men to default, some women take sexism as a challenge: Junko Tabei brought a female face to Japanese alpinism, climbing the nation's tallest peaks despite her 4-foot, 9-inch height, while Lhakpa Sherpa has made it up Everest 10 times, the female record. But sadder milestones also await some climbers, as in the case of Hannelore Schmatz. The fourth recorded woman to summit the world's highest peak was also the first of her gender known to die on the peak.

In 1979, Schmatz and her husband Gerhard, both experienced mountaineers who had summitted challenging Himalayan peaks before, decided to tackle Everest; at 50, Gerhard would be the oldest person recorded to summit at that point. (Hannelore was a spring-chickeny 39.) On the day they planned to summit, the couple were in separate groups. Gerhard summited without complications but noticed that conditions were poor, warning Hannelore via radio. Hannelore and her group chose to proceed, with Hannelore reportedly annoyed at the suggestion she cancel the summit attempt.

Reach the top she did, but on the way down, she became exhausted, making the fateful decision to overnight before continuing her descent. Hannelore succumbed during the next day's hike, asking her guide for water and then dying where she sat. Her corpse remained seated on the mountain, her face worn away by icy winds, until it was blown over the edge some years later.

Your body will likely remain on the mountain

If you die on Mount Everest, that's very likely where your body will remain. It is both extremely expensive and extremely dangerous to try to recover remains from the mountain; for example, a Nepalese guide and a policeman fell to their deaths in a 1984 attempt to recover the body of German climber Hannelore Schmatz, who had perished in 1979. This reluctance to throw the living at the dead and the price tag north of $100,000 means that some 200-plus bodies are somewhere on Mount Everest, where the cold means the bodies can remain preserved indefinitely.

Everest attempts have about a one-in-100 death rate, with the yearly rates varying with conditions on the mountain; notably, the descent directly after summiting claims more lives than summit attempts themselves. Some bodies can be recognized by their features and recorded gear, while some cannot be conclusively identified. The corpses, often in distinctive, colorful climbing gear designed to remain visible, now serve as landmarks for those making their own attempts to summit.

Doing it once is no guarantee of future success

You may hear summiting Everest described as a "once in a lifetime" event, but it's not so for the most avid thrillseekers and the Nepalese people whose cultures and livelihoods are tied to the mountain. Unfortunately, having successfully reached the top of the mountain and returned doesn't guarantee success or survival in future attempts, as illustrated in the sad tale of Sherpa Babu Chiri.

Babu Chiri was, by all accounts, an incredible mountaineer. To some of his fellow climbers, he was known by the nickname "Karma," which would seem unlucky for anyone, but especially someone who regularly courted danger. Chiri summited Everest 10 times in his 35 years, notching effectively superhuman feats like reaching the summit from base camp in under 17 hours, surviving a night at the peak, and summiting twice in one month. He was planning a truly bonkers feat of athleticism, going over the top from the Tibet side to the Nepal side and then turning around and reversing his route, when he died on a routine-for-him climb, falling into a crevasse while trying to take a picture. His wife and six children received condolences from the king of Nepal, who acknowledged Chibi's loss as one affecting the whole nation.

Even approaching Everest is challenging

Mount Everest is hostile to life, but the area around it is no picnic for people not acclimated to the conditions, and even those who have tried to adapt may succumb. Alexander Kellas, a British mountaineer and researcher working on the effects of high altitude on the body, died on the approach to the great mountain, a mere day before he would have arrived within view of it.

By 1920, Kellas had made eight expeditions to the Himalayas and had published an opinion that an ascent of Everest was probably possible for a very healthy and well-trained adult man. He had successfully climbed peaks in the Himalayas before and hoped to be the mountaineer to crack Everest, joining a reconnaissance trek in 1921. He brought supplemental oxygen equipment with him, planning to experiment with it as they ascended. In May, the group set out from Darjeeling in British India, from which they would need a month of overland high-altitude travel to reach Everest. During their route through Tibet, they all became ill with gastrointestinal trouble. Kellas was the sickest, but he remained so cheerful throughout the ordeal that his death surprised his fellow travelers, who named a peak they passed for him.

Three years later, two of the men with Kellas on this trip, George Mallory and Sandy Irvine, would be among the first Westerners to die attempting to summit Everest. Kellas' name was written alongside theirs on a memorial on the mountain.

Germs are there waiting for you

Mount Everest, high above the world in distant Nepal, may feel far removed from the world for many people, but the constant arrival of hundreds of coughing, sneezing, and defecating visitors means that any disease that affects the rest of the world eventually reaches base camp. In 2019, an unusually severe flu outbreak tore through the population of base camp, with dozens evacuated to Kathmandu by helicopter.

In 2021, COVID landed in base camp, dashing many climbers' dreams of summiting, even as the government of Nepal dismissed initial reports that the virus that shut the planet down had managed to reach the ceiling of the world. Given communal dining and a climate that rewards staying in with the others, instead of going out in the (freezing) fresh air, the spread of respiratory viruses like COVID and the flu is pretty much inevitable.

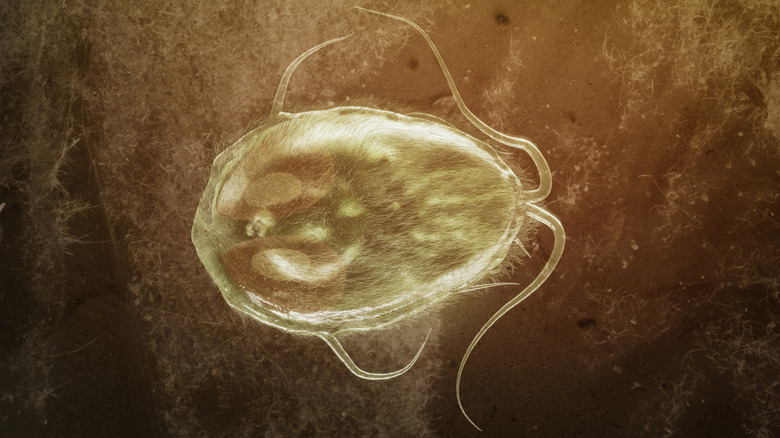

Additionally, diarrheal illnesses are a serious threat. Diarrhea is a common complaint at base camp, and while some can surely be explained by travel, new foods, stress, etc., transmissible infections are also a critical factor. Nepal generally does not enjoy excellent sanitation, much less in the extreme and remote areas around Mount Everest, and diarrhea is a major cause of death among the population of Nepal. Studies of water supplies at base camp have found contamination of water sources with organisms transmitted in human feces. More travelers necessarily means more feces, and so as more people visit Everest, more of them will catch and transmit pathogens unless and until stronger measures to control infections are taken.

Avalanches

Like quicksand, invisible ink, and secret passageways, avalanches are a feature of life prominent in cartoons that most Westerners will seldom seriously confront. The snowy slopes of the Himalayas, however, are one of the places where avalanches pose a distinct threat, with the sudden slides of snow and ice sweeping away any climbers unlucky enough to be in their path. (Fortunately, yodeling is not a serious risk factor; few noises are loud enough to destabilize a mass of snow.) Everest also sees a specific, similar-but-distinct phenomenon called a serac, in which chunks of glacier break from the main body and fall down the mountain, sometimes repeating their fall on subsequent days as the sun partly melts them.

Conditions vary year to year on Mount Everest, and with them the risk of avalanches. In general terms, heavy snow and high winds are the danger signs, as these can deposit snow on steep or unstable surfaces from which a mass is more likely to slide as a unit, overload previously stable snowpacks below, and turn individual snowflakes into fused ice crystals.

The 2014 and especially 2015 climbing seasons were particularly bad years for avalanches on Everest, with 16 guides dying in a single event in 2014 that closed the mountain for the rest of the season. The 2015 avalanches were triggered by a strong earthquake in April that battered Nepal; 22 people died at base camp, and the mountain was again closed after a strong aftershock in May.

Medical care is good – considering

The area around Mount Everest Base Camp does have medical professionals, hard-working and well-trained staff who provide the best care possible under the circumstances. However, the cold, altitude, remoteness, and terrain are certainly intense circumstances to overcome, and care simply cannot reach the expectations of more hospitable areas. Supplies come in on yaks, so if something goes wrong with the yak, you might not get what you need; helicopters can provide support in emergencies, weather permitting. All power is solar, so sudden cloud cover can cut off the juice without much warning. Limited running water means that even hygiene itself must be subject to triage. Even the buildings themselves may be impermanent, as some installations themselves lie on slowly shifting glaciers.

In many cases, injured or sick people must be sent to better-equipped facilities at lower altitudes after diagnosis and stabilization. One benefit of the influx of outside tourists into the high Himalayas is that the medical professionals who come to treat them also treat the support staff and local population, who because of the area's remoteness and Nepal's relative poverty, may otherwise struggle to access medical care.

Blizzards

With both timing and maneuvering ability critical for survival of Everest's dangers, a blizzard represents a threat just as severe as falls and low oxygen. Reduced visibility and dangerous winds can stall progress even as falling and blowing snow makes climbers colder and walkways more treacherous. And if a blizzard pins explorers down in one spot for too long, it can mean the premature end of a journey and a life.

The most famous blizzard to hit Everest during a recent-ish climbing season was in 1996, recounted in John Krakauer's disaster-lit classic "Into Thin Air." (Krakauer got lucky in more than just book sales: He avoided the worst of the conditions and summited shortly before the disaster struck.) Adventure tourism had drawn more people to Everest, and the Nepalese government had increased the number of available permits, resulting in overextended guides, too many inexperienced climbers, and crowding on the mountain that slowed teams' advances as they waited behind other groups.

When a blizzard walloped the mountain and those on it the night of May 10, it hit the underprepared and straggling groups on the mountain like an angry fist. Some people were trapped near the summit; others, descending, couldn't find their way forward to the nearest camp. Eight people died, mostly of hypothermia, but with at least one simply disappearing on the mountain, and some survivors required amputations due to frostbite. This was the deadliest recorded day on Everest at the time, surpassed eventually by events in 2014.