The 11 Worst Bridge Disasters In US History And Why They Happened

Infrastructure is easy to take for granted. It's something that everyone relies on all day, every day, but tends be to overlooked until something catastrophic happens. And here's the thing: According to experts, catastrophic things are going to keep happening because the U.S. has the perfect storm of aging infrastructure, a lack of motivation and money to fix it, and an ever-increasing amount of stress on those ever-increasingly compromised structures, including bridges. In 2023, National Geographic spoke with some of the country's top engineers and experts, and they had some startling comments about bridges. Amlan Mukherjee of WAP Sustainability Consulting shared a terrifying thought: "If you have to think in terms of catastrophe, we're already there." (We already know that the destruction of many major mega-buildings would be devastating for the entire nation.)

Estimates suggest that out of the 617,000 bridges in the country — give or take — around 10% of them fall into the category of being significantly compromised. What does that mean? About 178 million times a day, someone crosses one of those dangerous bridges. Are ya feelin' lucky?

And there have been some terrifying instances where we've seen exactly what a catastrophic bridge failure means. If we're lucky, it happens when there's no one around. When we're unlucky? It happened in the middle of rush hour, and some collapses have killed dozens of people. While they're sometimes precipitated by unsafe infrastructure, sometimes, it's the result of a freak accident. Let's talk about some of the worst bridge collapses the U.S. has experienced, and what we've learned from them.

Missouri, 1981: The Hyatt Regency skybridge collapse

Not all bridges cross rivers and roadways, and one of the deadliest bridge collapses in U.S. history actually involved concrete skybridges built across the lobby of a massive Hyatt Regency hotel in Kansas City, Missouri. On July 17, 1981, as couples gathered with plans to laugh and twirl the night away at an event in the hotel lobby, spectators freely took to the second- and fourth-floor skybridges. But as the crowds grew on the skybridges, disaster struck.

Local news crews were already on hand to film the dancing couples that day, when the moorings securing the skybridges in place failed and the structures collapsed on the dancers, killing 114 and injuring more than 200. Rescue workers spent hours recovering bodies and cutting survivors free — sometimes amputating limbs in order to do so — and it was later discovered that the carnage had been easily avoidable. When the bridges were built, the lower one was anchored to the higher one — without taking into consideration that the higher bridge was now supporting twice the weight it had been built for.

Brent Wright spoke with NPR about the disaster: His mother and stepfather were among the dancing couples, and their last moments were filmed by news crews. "It's a really nice thing to know that at least that night they were enjoying themselves and living their lives to the fullest, you know, still newlyweds. Initially, after a tragedy like that, those things are hard to watch."

Alabama, 1993: Big Bayou Canot rail bridge

The 1993 collapse of Alabama's Big Bayou Canot bridge only happened because of a strange set of circumstances, bad weather, and delays. It started with a towboat and six barges that were being piloted along the Mobile River as a spell of bad weather made visibility next to nothing. The towboat pilot ended up getting diverted into the Big Bayou Canot, and in the process of trying to find somewhere to wait out the weather, the towboat pilot collided with the supports of a railway bridge.

The boat didn't collapse the bridge, but it did bend the supports. Still, things were about to get worse, as a train that was supposed to have passed half an hour before had been held up by an air conditioning malfunction. The delayed train crossed the bridge eight minutes after the collision, and the entire structure collapsed into the mud and water.

By the time rescue workers had cleared the wreckage, 47 people were dead, and more than 100 were injured. Among the survivors was then-11-year-old Andrea Chancey, who spoke with the Associated Press (via Alabama) in 2018 and said that she was still dealing with the trauma: "I smell the oil. I see the fire, I hear the screaming." Chancey lost both of her parents in the accident, and as one of the survivors was passed out of a burning passenger car by unseen hands, she was dubbed the "miracle child" in media coverage.

California, 1989: Cypress Street Viaduct collapse

When a devastating earthquake hit Oakland in 1989, the majority of deaths happened on the Cypress Street viaduct. The quake was a 7.1 on the Richter scale, and resulted in a bridge failure so catastrophic that it took 90 hours for the last survivor to be rescued. In the end, accounts vary as to how many people were killed. Some sources say 35 died on the bridge, with others say the death toll was 42.

The bridge had been built in a way that was supposed to help reduce traffic. There were two levels to the little-over-one-mile bridge, which consisted of five lanes on both levels and passed over more ground-level traffic. However, it would later be determined that it simply hadn't been built to withstand the stress of a major earthquake.

The Oakland Tribune photographer Michael Macor went to document the scene, and he described it years later to the San Francisco Chronicle. He drove through a city reeling from the earthquake, saying, "I still wasn't prepared to see what I was about to see around the corner. ... It looked like a movie set. It didn't look real at all." The top deck collapsed onto the lower one, leaving rescuers — and the nearby community — to build makeshift ladders in an attempt to reach survivors. One — Chris Mitchell — told KPIX News that he was trapped between the bridges: "I just happened to be in between two crossmembers, and there was enough space for me to live."

Colorado, 1904: Eden train wreck

Newspaper reports from the August 11, 1904 edition of The Colorado Transcript are harrowing stuff. They covered a bridge failure and subsequent train wreck that had happened a few days prior, and it was reported that of the 125 passengers, between 80 and 100 were assumed dead. They painted a grisly picture: Other trains — one filled with doctors and rescue workers, the other with coffins — were dispatched to the scene, where a collapsed bridge had plunged a train into the muddy, rushing creek below the river. The scene was so chaotic and the river was running so violently that several train cars were missing and presumed to have ended up somewhere downstream.

The creek bed was an arroyo — an area that was dry most of the time, but flooded with storms. Following the collapse, an investigation confirmed that the bridge had been built with a standard form of construction and that it had been in service for years. Exactly what happened remains conjecture.

It's believed that a wave hit the train as it crossed over the bridge, and that wave may or may not have also been carrying the remains of a bridge that had broken free and collapsed upstream. Floodwaters carried the train cars away with them, drowning most inside. The fireman, David Mayfield, survived to recall (via Structure), "I scarcely know how it happened, as I was dazed in the mud on the bank of the creek. It all happened so quickly — and, my God, it is so terrible."

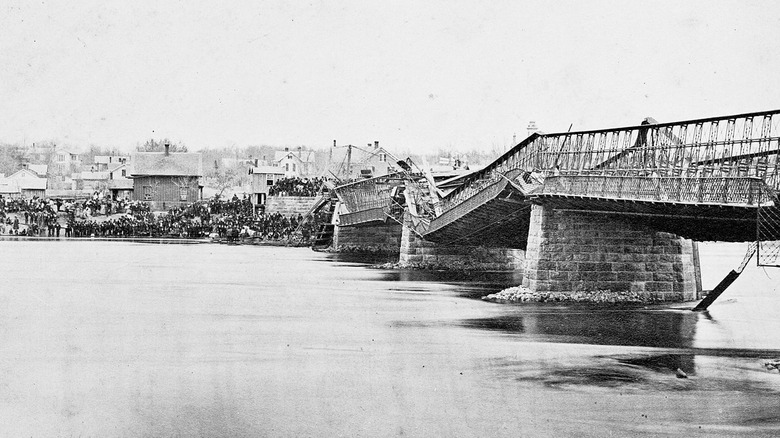

Ohio, 1876: The Ashtabula train disaster

Two engines. Around 160 people. A blinding blizzard, a failing bridge, and a deadly 70-foot plunge to the ground below. Those are the main players in the Ashtabula train disaster, and it's awful stuff. The engines — the Socrates and the Columbia — were pulling a train from Buffalo, New York, to Cleveland, Ohio, on December 29, 1876. The lead engine Socrates had just made it across the bridge spanning the Ashtabula River when the bridge collapsed. Nearly everyone on board was killed, but one survivor told of an awful sight.

J.E. Burchell escaped the wreckage, and was later quoted (via Cleveland) as saying, "[It was a] terrible, but picturesque sight. It was a heart-rending scene. The mangled, bleeding bodies writhed in the terrible tortures around them. Some died with prayer and some with shriekings of woe on their lips."

Around 80 people died, and nearly 50 of the recovered bodies were mangled beyond recognition. The collapse led to a massive investigation to try to determine why the 11-year-old bridge had suddenly and catastrophically failed, and whether or not similar bridges were in danger. It was eventually ruled that there had been defects present in the bridge from the time of construction, and inspections that had been carried out had every chance to catch the problems. It remains one of the deadliest train accidents in history.

Illinois, 1873: The Truesdell bridge tragedy

The Truesdell Bridge tragedy is kind of the ultimate irony. When it was built, the bridge was designed and approved by a city that was sick and tired of wooden bridges collapsing and getting washed away by flood waters. In 1868, they approved new plans, in spite of the fact that alarm bells had already been raised by those who thought this new design was actually a pretty bad idea.

It was. Four years after it was built, it collapsed — and media coverage referred to Lucius Truesdell's bridge design as The Patent Wholesale Drowning Machine. When it went down, the iron bars folded in on themselves, trapping people underwater in an iron cage. And there were a lot of them, mostly women and children walking in a baptismal procession from the church to the river. One survivor, Gertie Wadsworth, later recalled (via the Associated Press), "You could look down and see their faces. They couldn't get to the surface because all that iron was on top of them. It's frightening to look down, but to look up and to see daylight, to be only 12 inches from air?"

Several other Truesdell-designed bridges had collapsed in the previous years, and it was widely condemned from the beginning. Engineers pointed out that the bridge's foundation was way too lightly built to support the actual bridge, and investigations into the incident generally agreed. Truesdell, meanwhile, continued to defend his bridge and the design. Of the 200-odd people who were on the bridge, 46 died.

Maryland, 2024: The Francis Scott Key Bridge

It's a little terrifying to think about how much we're really at the mercy of technology, but that's exactly what Edward Tenner — a disaster expert, historian, and author of "Why Things Bite Back" — does all day. After the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore, Maryland, he told The Washington Post, "This might have been a case where there were just an unlikely series of failures. ... [But], given the potential for damage like this, there should have been more redundancy. There shouldn't have been one point of failure that could lead to a catastrophe."

And that's what was pretty immediately reported: A shockingly massive cargo ship called the Dali lost power, collided with a bridge pier, and sent the entire thing crashing into the water below. Amid the finger-pointing that inevitably followed, one of the things that was widely condemned was the inability of infrastructure to keep up with implementing security measures to guard against collisions of cargo ships of seemingly ever-increasing size.

Casualties included six construction workers who were on the bridge at the time of the collapse, and it was also very quickly reported that it was going to have devastating, far-reaching impacts on the U.S. economy. It shut down a key access point into the East Coast, and — coupled with other difficulties in key waterways like the Panama Canal — it was quickly predicted that long-term impacts were going to be felt nationwide.

West Virginia, 1967: Point Pleasant's Silver Bridge collapse

Of all of the deadliest bridge disasters in world history, it's West Virginia's Silver Bridge that has perhaps the strangest history. It was located in Point Pleasant, and yes, that's where the bizarre cryptid known as Mothman is said to reside. But first, the bridge. When it opened in 1928, it was a huge deal: It connected West Virginia and Gallipolis, Ohio, with a pretty revolutionary structure. Fast forward to 1967, and the bridge collapsed and killed 46 people. An eyewitness described the scene, saying (via Popular Mechanics), "It didn't just fall into the river. It sort of slithered like a snake, then it buckled and cars began falling off sideways."

It was later found to be the fault of a single iron bar that had corroded, snapped, and started a chain reaction that devastated the area. Understandably, the entire area struggled with grief, loss, and that age-old question: "Why?" And here's where things get weird.

Mothman sightings had started just the previous year, with countless people convinced that they had not — as local wildlife experts insisted — seen a sandhill crane, but a mysterious, winged monster. John A. Keel's book, "The Mothman Prophecies," suggested that the appearance of the Mothman was a sort of otherworldly herald, warning of imminent disaster. Keel claimed that there were other warnings issued, too, and with the Silver Bridge tragedy as so-called proof, the Mothman mythos was firmly cemented into one of the U.S.'s favorite cryptids. Go figure.

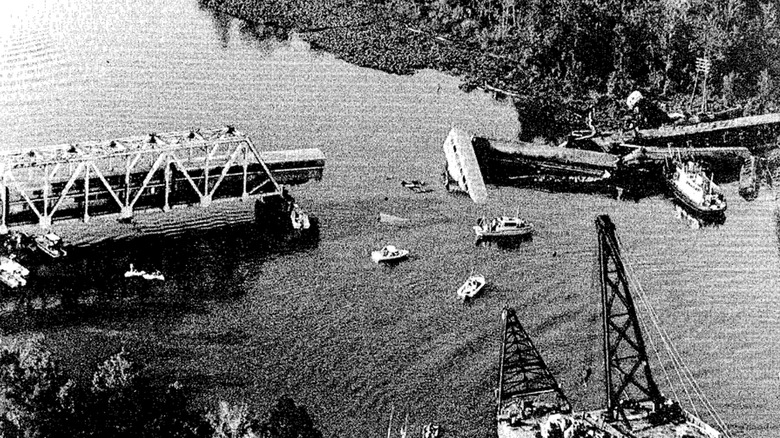

Florida, 1980: The Sunshine Skyway collapse

The collapse of Baltimore's Francis Scott Key Bridge made headlines in 2024, including in the Tampa Bay Times, which also reported on the eerie similarity between the Maryland disaster and one that claimed the lives of 35 people in 1980. That's when the Sunshine Skyway Bridge was hit by a cargo ship that had gotten disoriented in bad weather.

The bridge collapsed, and one of those interviewed at the time was a paramedic named Jay Hirsch. He crossed the bridge as it happened, recalling, "It thought at first it was thunder. Then something hit the bridge so hard it knocked my car out of its lane. I kept going till I got across. When I looked back, I saw it. My God, the bridge had gone down." Among the vehicles that didn't make it off was a Greyhound bus, and in 2020, the Tampa Bay Times interviewed some of the rescue workers that had been on-site that day. Bizarrely, two of them were bridge inspectors for the Department of Transportation, and they had been on their way to inspect the bridge that day.

Instead, they found themselves helping to recover the bodies of the drowned. Michael Betz and Robert Raiola pulled people from their bus seats and swam with them to the surface several times. There were no survivors. Decades later, Raiola said he was still haunted by one thing he saw in the wreckage: a diaper bag.

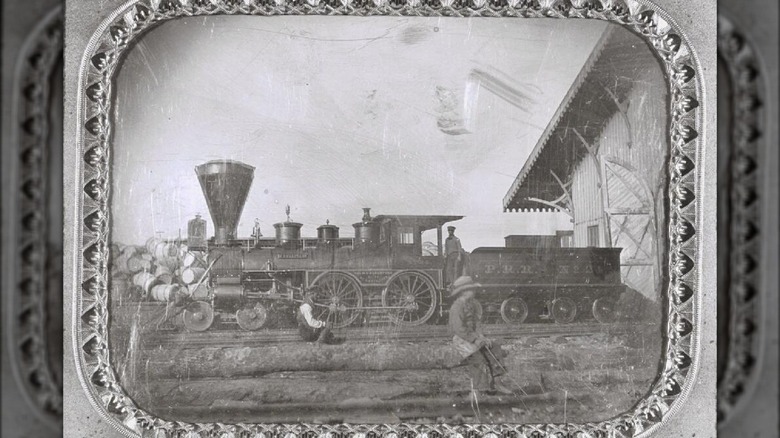

Missouri, 1855: The Gasconade Bridge disaster

There are plenty of occasions when taking shortcuts might be perfectly acceptable. When building a bridge? Not so much — but that's exactly what happened in the lead-in to the collapse of Missouri's Gasconade Bridge. In a nutshell, the Pacific Railroad had taken on the task of connecting St. Louis and the Pacific Coast. There were all kinds of delays, and corners got cut ahead of an inaugural, celebratory train journey that would carry 600 people from St. Louis to Jefferson City. There were two bridges that the train would cross, and one was erected hurriedly as a temporary measure.

The bridge collapsed under the weight of that celebratory train (pictured), although one small mercy was that only 31 out of 600 people died in the wreck. Hundreds more were injured, and one St. Louis paper published this somewhat fanciful description of the scene (via Structure): "Immediately after the accident, the heavens grew dark and black, as though the night had come. ... hoarse thunder bellowed its cruel mocking's at the woe beneath. It seemed as if the elements were holding high carnival over the scene of slaughter."

The backlash was swift, and although the exact details were never agreed upon, it seems as though the train's speed, coupled with uneven weight distribution and rushed construction, all came together to end in tragedy. On the plus side, the disaster went a long way in pushing through requirements to have trained engineers overseeing future construction.

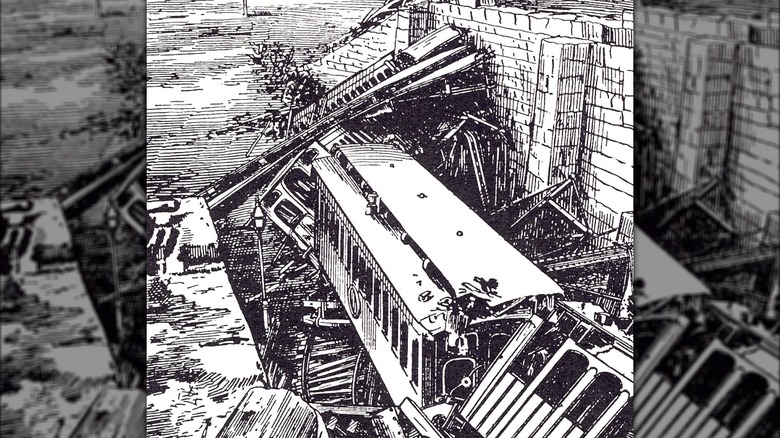

Massachusetts, 1887: The Bussey Bridge disaster

A description of the Bussey Bridge disaster comes (via Structure) from the engineer who drove the train. He testified that as he approached the bridge, "there was no appearance whatever of danger." An engineer with 30 years of experience, he saw no signs that, within moments, dozens of people would be dead. "However, as I cast a glance at the train behind, I saw the first car swing inward and topple over as though about to fall, and while I still looked, amazed and bewildered, the second and third cars tipped over in similar positions, and all finally jumped the track."

When inspectors from MIT were sent to the scene, they chalked the bridge collapse up to a few things: faulty materials, bad welding that had finally broken under the strain, a design that was destined to fail, and a complete lack of oversight. The investigation was also quick to point out that recommendations for upgrades had been made in 1881, then were completely disregarded.

Part of the problem wasn't just the bridge's construction, but also a strange part of the design that hid vital components requiring regular safety inspections. It was only once the bridge had collapsed — killing 23 people and injuring hundreds — that those hidden components were found to be wildly defective: The Boston Globe wrote, "Bad in contract, bad in make, bad in testing, and very bad in general." Click here to read more about the most dangerous railways in the world.