Athletes Banned For Life From Their Sports

No one expects sports stars to be perfect angels, but there is a limit to the amount of bad behavior they can get away with. Whether it's getting involved in doping, match-fixing, gambling on games, or behaving in other ways that bring their sports into disrepute, there are plenty of ways athletes can screw up badly enough that fans and official decision-making bodies alike won't stand for it.

Sometimes, this might result in crazy stories of athletes being stripped of their Olympic medals or being dropped by sponsors like Nike. Other times they might face one of the longest suspensions in sports history.

But for some violations, no combination of these punishments is enough to see justice done. In these cases, the guilty athlete is made an example of by being banned from their sport for life. While very occasionally these decisions are rescinded at some point, or the fairness of them is debated even long after the person in question is past playing age (or dead), in general, being banned for life is as permanent a punishment as it is intended to be. It is the ultimate shame on an athlete's legacy. Here are some of the athletes who have been permanently barred from sports ranging from baseball to sumo wrestling to equestrianism.

Jontay Porter fell foul of sports gambling rules

Radical changes in sports betting in recent years mean you can now legally make bets in 38 states. But there are still rules about what you can't do when it comes to betting, especially if you are an athlete.

Jontay Porter of the Toronto Raptors broke several of those rules. An investigation by the NBA in 2024 found that he not only bet on basketball games, he also gave inside information to gamblers, and, worst of all, he faked injuries so bets his acquaintances placed would pay out. Porter was subsequently banned for life from the NBA. Raptors President Masai Ujiri said, "My first reaction is obviously surprise, because none of us, I don't think anybody, saw this coming" (via the AP/CBC).

Ujiri might have been talking about Porter as a person and the unlikelihood he would get involved in this kind of scheme. But he should have seen the problem more generally coming from a mile away. Legal sports gambling is only getting bigger, which means examples like Porter's are "just the tip of the iceberg," Sean McKeever, a professor of philosophy, told Vox. "The corrupting forces are powerful ones. ... And bettors stand to make significant sums if they can extract valuable information and behavior from players and those around them." Professor Andrew Zimbalist, an expert on the economics of sports, told MarketWatch, "...it's really likely it's going to happen a lot more. Everybody, even if they are rich, wants to get richer."

Shoeless Joe Jackson might be innocent

Joseph Jackson, better known by his nickname "Shoeless Joe," escaped poverty growing up in South Carolina at the turn of the century by becoming a baseball phenom. He was playing for local teams by the time he was a teenager, and was signed to the big leagues by the time he was 21. He played for various teams between 1908 and 1915, until he finally landed a spot on the Chicago White Sox. His team won one World Series in 1917 and headed to a second one two years later. Jackson's career looked to be a standout one by any measure. Then he got himself mixed up in the Black Sox Scandal of 1919.

Some of his teammates were accused of throwing the series to the Cincinnati Reds after being paid by gamblers. While several admitted to it, Jackson did not, and his teammates swore they didn't tell him what they were doing. Despite this, Jackson was banned from baseball for life. He went on to try to live anonymously and ran a dry cleaning business.

In 1942, Jackson gave an interview to The Sporting News (via his official website) in which he swore, "Regardless of what anybody says, I was innocent of any wrongdoing. ... If I had been out there booting balls and looking foolish at bat against the Reds, there might have been some grounds for suspicion. I think my record in the 1919 World Series will stand up against that of any other man in that series or any other World Series in all history."

Tonya Harding pleaded guilty before being banned

By the time the first figure skater took the ice at the 1994 Winter Olympics, there had already been more than enough drama between the competitors, thanks to a notorious sports rivalry that took things too far. Six weeks earlier, an unknown man had attacked Nancy Kerrigan with a metal baton, walloping her knee. Amazingly, she was healed enough to skate at the Games, along with fellow Team USA member Tonya Harding. Kerrigan eventually won silver while Harding came eighth.

Failing to medal was only the beginning of Harding's problems, though. Soon, the conspiracy to take Kerrigan out of Olympic contention by men connected to Harding, including her ex-husband, was discovered. Harding was also charged, and while prosecutors believed she was heavily involved in the plot, they agreed to a plea bargain in which she only admitted to hindering prosecution. Part of the deal required her to resign her membership in the United States Figure Skating Association, although this point would become moot since the association ended up banning her for life.

Since then Harding has told her version of the story in multiple formats, including in the Oscar-winning biopic "I, Tonya." She married, had a child, and tried to stay anonymous, although she found that almost impossible. At one point she took up boxing and fought in six professional bouts. She says she has apologized to Kerrigan many times, although the latter disputes this.

Lance Armstrong took doping to new levels

Lance Armstrong was infamously a participant in and ringleader of one of the biggest doping scandals ever to hit the sports world. This forever stained his impressive legacy of winning a record seven Tour de France titles and a bronze medal at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney. Considering he also beat an advanced case of testicular cancer in the middle of his career, his abilities seemed superhuman.

Turns out, they were. Armstrong was constantly accused of doping during his career but always denied it. It was only in 2012, after several former teammates admitted to doping and the close of a federal investigation into the accusations, that Armstrong was banned for life from cycling events. He was also stripped of his Tour de France titles and his Olympic medal. In 2013, in a sit-down with Oprah Winfrey, Armstrong finally confessed to his years of juicing.

Armstrong's punishment wasn't just a lifetime ban from cycling, but various temporary and permanent bans from many other sports as well. For example, he was told he couldn't participate in a 2012 marathon and a 2013 swim meet because they were run by organizations that were signatories of the World Anti-Doping Agency code. This also kept him from continuing to compete in many of the triathlons he'd entered before his ban became official. Some of his bans on entering lower-level competitions were lifted in 2016, however, his lifetime ban from cycling remained firmly in place.

Wakanoho Toshinori was disciplined for marijuana use

Sumo wrestler Wakanohō Toshinori was born Soslan Gagloev in Russia and started his sports career as a talented young wrestler. However, he couldn't keep himself below the 264 lb. weight limit needed to compete in the Olympics, so his father encouraged him to try sumo wrestling instead. By 17, Wakanohō was rich and famous in Japan. By 20, he was in disgrace and taking the sport down with him.

In 2008, Wakanohō was arrested for drug possession. He was caught with marijuana, which might sound tame by U.S. standards but was a serious crime in Japan. He was quickly banned from sumo for life, the first wrestler to be barred for drug use. All sumo wrestlers were subsequently drug tested, resulting in another two being banned for marijuana use just a month after Wakanohō was. Adding to the drama, Wakanohō then claimed he had been paid to throw sumo matches and that many others were involved in match-fixing as well.

After being thrown out of the Japanese sumo world and now going by his birth name, Gagloev tried to make it in American football, playing at Webber International before transferring to the University of South Florida, and eventually trying out for the NFL. He was unsuccessful, however, and eventually returned to sumo — outside Japan, at least — competing in bouts organized by the International Sumo League.

Foekje Dillema faced cruel questions

In 1999, the International Association of Athletics Federations named Dutch track and field athlete Foekje Dillema the Female Athlete of the Century. This was an especially meaningful honor for the runner, who was then in her 70s. She'd won four medals at the 1948 Summer Olympics in London, but only two years later her career was over. A secretive physical examination was conducted by the Dutch governing body of her sport and she was banned for life. Why? It's impossible to know since no details or results have ever been released. Another version of the story is that Dillema was banned because she refused to submit to the gynecological exam.

What we do know is that Dillema was assigned female at birth, raised as a girl, and presented as a woman her whole life. A genetic test of DNA from her clothing after she died and published in the journal of the British Association of Sport and Medicine found she "had a 46,XX/46,XY mosaic condition with a rare origin ... leading to hyperandrogenism from her puberty." In other words, sex and genetics are more complicated than most people think. But according to Dr. Kamlesh Madan, "She was definitely a woman and she should never have been expelled by the Athletics Union. No way" (via UPI).

After her death in 2007, Dillema's personal best record in the 200m, which had been invalidated after her ban, was finally reinstated.

Ángel Matos let his anger get the better of him

You expect to see some pretty violent kicking when watching an Olympic taekwondo match. The problem for Cuban competitor Ángel Matos, however, was that those moves should only be directed at your opponent, not the referee. Matos was winning the bronze medal match at the 2008 Games in Beijing when he appeared injured. The referee believed Matos exceeded the allowed minute of injury time and disqualified him, meaning his medal dreams at that Olympics were over. In a rage, he ran at the ref and kicked him in the head. He was dragged away by security, and the spectators who had witnessed the incident also heard the announcement just minutes later that Matos was banned for life from the sport.

"It's something I still regret until this very day because I didn't want my sports career to end this way," Matos told the Havana Times in 2018. Beijing was his third Olympics, and he'd won gold in the 2000 Games in Sydney. But while Matos might take responsibility for what he did, he also made claims of match-fixing against others involved. "They tried to buy me off that day so that I would lose the fight. My trainer and I were both offered money and we refused. That's why I still say that they bought the referee off, because ever since the match began, he bothered me."

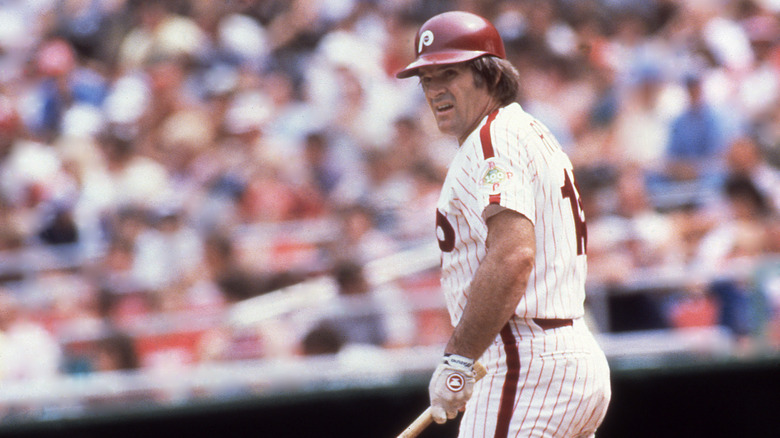

Pete Rose did bet on baseball

After the Black Sox scandal during the 1919 World Series, Major League Baseball made it an official rule that baseball players could not bet on baseball games, especially ones they themselves played in. This was not an obscure rule or one that fell by the wayside in the ensuing decades. So when it was revealed that record-breaking hitter Pete Rose was doing exactly that while both playing and managing the Cincinnati Reds in the mid-1980s, there was no way he could avoid the prescribed punishment of a lifetime ban.

The event was so notorious it became known as "the Banning of Pete Rose." The official document involved was even auctioned off at Christie's in 2021, where it went for $150,000. To save face, Rose agreed to the banning as long as MLB didn't state that they had officially determined he bet on baseball, just other sports.

Despite his achievements as a player, due to changes made to the rules in 1991, Rose is also not eligible to be included in the Hall of Fame because of his ban. He has tried to be reinstated several times. Now that sports gambling rules have been relaxed across much of the U.S., his lifetime ban was again being discussed in 2023, however, the commissioner made clear the ban was there to stay, regardless.

Aleksandrina Naydenova fixed her tennis matches

While it's the athletes at the top of their game that get the most attention when they are suspended or banned, less talented players can face serious consequences for their actions as well. Take Bulgarian tennis player Aleksandrina Naydenova. Her career-high WTA singles ranking was just 218, which she achieved in 2019. We'll never know if she could have achieved a higher place than that because it was the same year she was banned for life for match-fixing.

Naydenova was not the only one involved, however. In fact, she was one small part of the biggest match-fixing ring tennis had ever seen, organized by a man named Grigor Sargsyan and involving at least 180 players from 35 countries. Players would receive texts before their matches telling them how well — or not — to perform. The same information would be sent to the gamblers involved in the ring, allowing them to make bets they had no chance of losing.

In 2020, an investigation found that Naydenova was involved in at least 12 match-fixing incidents over a four-year period. Her temporary ban from any official tennis competition was made permanent, and she was also fined $150,000.

George H. Morris did unspeakable things

Most athletes who receive lifetime bans do so during their careers; after all, what is the point of banning someone who is no longer competing? But sometimes, the behavior involved is so bad that the ban is more a statement that the sport wants nothing to do with that person than an actual way to keep them from participating in competitions. This was what happened with the then-81-year-old equestrian George H. Morris in 2019.

Morris was a legend of the sport, having won a silver medal in show jumping at the 1960 Olympics and later coaching both the U.S. and Brazilian Olympic equestrian teams. Two of the most prestigious awards given out by the United States Horse Jumping Association were named in honor of him. However, it is alleged that during his many decades at the top of the sport, it was an open secret that he was abusing underage boys.

After some of his accusers came forward, the U.S. Center for SafeSport launched an exhaustive investigation, during which both Morris and his accusers were allowed to tell their sides and present evidence. After the lifetime ban was handed down in 2019, the chief executive of the Center for SafeSport released a statement (via The New York Times) saying, in part, "No matter how big a figure is in their sport, or how old the allegations, nobody is above accountability."

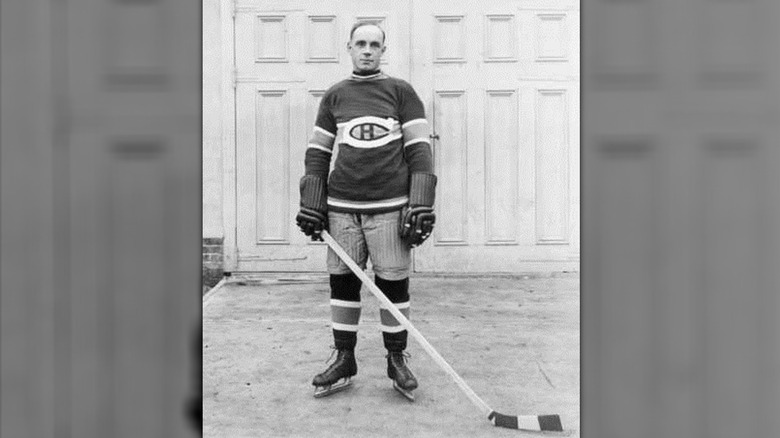

Billy Coutu was eventually allowed to return to the NHL

The honor, as it were, of being the only NHL player ever banned for life goes to Billy Coutu. He'd been playing in the league since it began and had been captain of the Montreal Canadiens. He was also a notable hothead, even in a sport where on-ice brawls are expected.

Before the 1926-27 season he'd been traded to the Boston Bruins, who ended up making it to the Stanley Cup Final that year. It had been considered a particularly fine year for the NHL, which now had 10 teams. But on April 13, 1927, not only was Coutu about to lose the finals in Game 4 with his team, but by the next day, he would be banned for life from his league. Amazingly, this ban had nothing to do with the fight that broke out during the game itself and required police to break it up. After the game was over, Coutu, along with the Bruins' manager and several other players, jumped one of the referees in a hallway. The reason Coutu was the only one to receive a lifetime ban, however, was that when another referee tried to stop the assault, Coutu attacked him too.

The ban was only enforced for two years. Coutu was eventually allowed to play and coach in the minor leagues and then given permission to return to the NHL, although he never played in another major league game.