The Truth About The Black Sox Scandal Of 1919

"Say it ain't so Joe! Say it ain't so." Whether myth or real, the words spoken by a broken-hearted young boy to his baseball hero rings as the immortal phrase of the 1919 Black Sox Scandal. In many ways, the Black Sox Scandal ushered in a new era in professional baseball. At the dawn of the 1920s, the game was about to take a major transformation: In the winter of 1919, Babe Ruth was traded from the Boston Red Sox to the New York Yankees and by the end of the 1920s, Ruth would become the face and father of baseball, even a century later. According to Baseball Reference, Ruth's ascension with his home-run hitting, the banishment of the spitball, and the improvement of in-game strategies marked the end of the Dead Ball era and the beginning of Baseball's Golden Age.

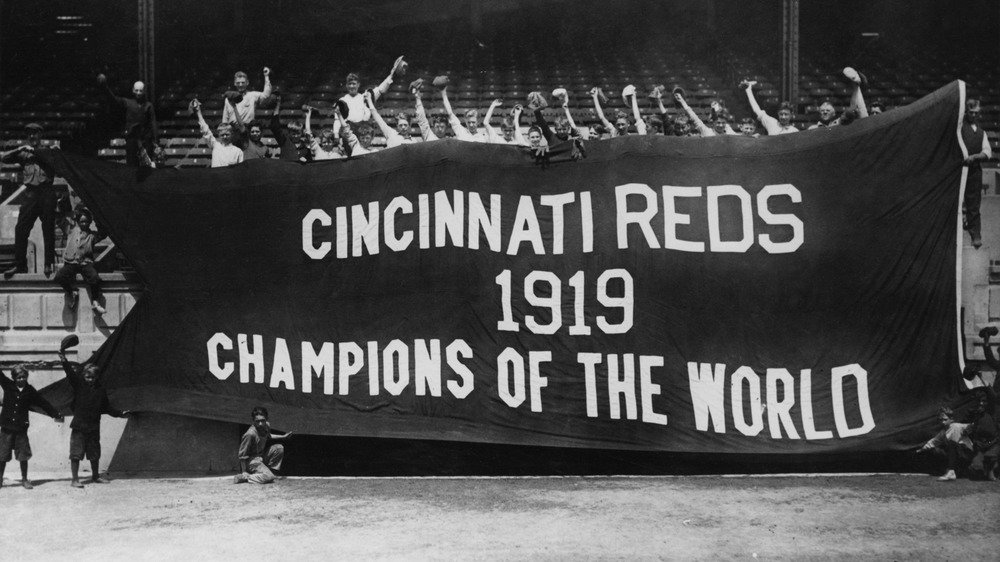

However, at the beginning of this evolution was the 1919 World Series between the Cincinnati Reds and the Chicago White Sox. What was thought was going be an easy series victory for the Sox became a national scandal that rocked the American pastime to its knees. And for eight of the White Sox players, it was the beginning of the end of their careers. The Black Sox Scandal has been immortalized in literature, film, documentaries, and Americana folklore, but what is the real story of the Black Sox Scandal? Here is the truth of the Black Sox Scandal of 1919.

The 1917 Champion White Sox

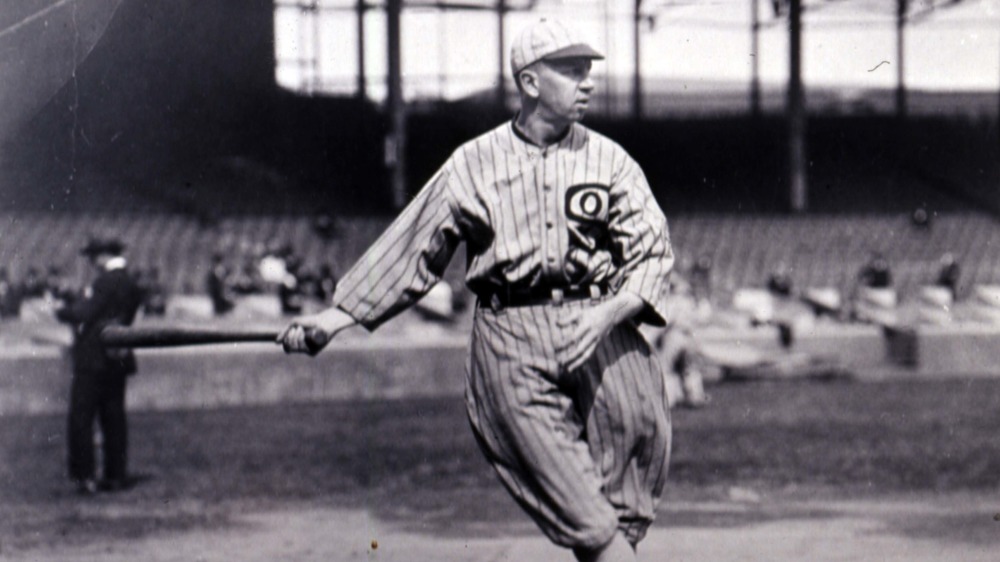

Two years prior to their appearance in the 1919 Worlds Series, the Chicago White Sox were celebrating a World Series championship. The team had spent the early 1910s building up a strong ball club that boasted four different Hall of Fame players: second baseman Eddie Collins, catcher Ray Schalk, and pitchers Red Faber and Ed Walsh, according to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR). Despite the talent, the team's championship chances skyrocketed during the 1915 season when they traded for Cleveland Indians star outfielder, "Shoeless" Joe Jackson.

Jackson had spent the 1910s developing into one of the best hitters in baseball before being traded. That being said, Jackson struggled during the 1915 season after the trade, and Chicago lost out of the pennant. The next year, Jackson and the rest of the team rebounded and battled the Babe Ruth-led Boston Red Sox for the American League pennant. Boston took the 1916 pennant and won the World Series.

In 1917, all the chips were aligned for the White Sox. According to Bleacher Report, the Sox led the majors in runs scored (656), stolen bases (219), on-base average (.323), and earned run average or ERA (2.16). Jackson and fellow outfield Happy Felsch were the standout players at the plate. In the World Series against the New York Giants, Eddie Collins' .409 batting average and Red Faber's three victories led Chicago to their first World Series title since 1906. Despite the championship, a storm was rising in Chicago's dugout.

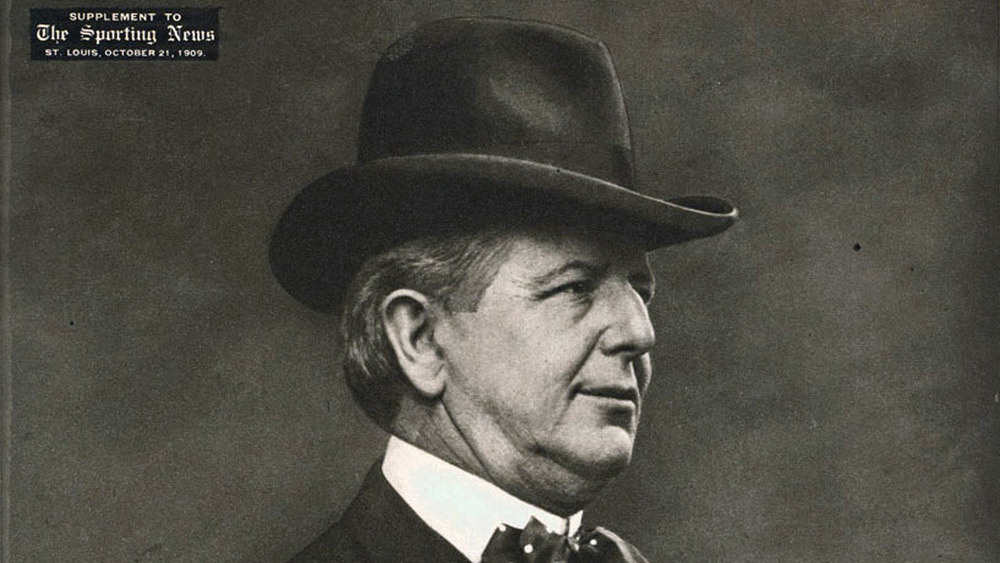

No One Liked White Sox owner Charles Comiskey

While the joys of winning can a lot of times cure many ill feelings, that was not the case for the White Sox. It is not shocking for players to feud with management. However, the relationship between many White Sox players and owner Charles Comiskey was very sour.

To the public, Comiskey was Santa Claus. According to The Dead Ball Era, Comiskey allowed local organizations to use his field, Comiskey Park, free of charge, invited hundreds to his estate in Wisconsin, tithed his revenue to the Red Cross during World War I, and paid for the college tuitions of the sons of pitcher Ed Walsh and catcher Billy Sullivan.

However, with his own team, Comiskey was more Scrooge than Santa. While other teams cared for the players' uniforms, Comiskey cut down on the laundry bill, forcing players to play in dirty uniforms or clean it themselves. He gave the team $3 daily for lunch while other teams gave $4, and after promising a bonus for winning the 1917 pennant, instead of cash, he gave the team cheap champagne.

However, as discussed in ESPN's docuseries, "Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame...," Comiskey seemed to have enough cash for well-educated players on his team. While Happy Felsch and Shoeless Joe Jackson were underpaid, captain Eddie Collins was the second-highest-paid player in the American League (AL) at $15,000. Collins was a college graduate, while Felsch had only a sixth-grade education, and Jackson had none.

Chicago: The Land of Gangsters

Before Prohibition was put into effect in January 1920, and well before the rise of Al Capone, Chicago was already the land of gangsters. According to Chicago Gang History, the first gangs did not spring up until the 1830s, and they did not develop real power until after the Civil War. According to The Culture Trip, pre-Prohibition Chicago gang activity was so rampant, neighborhoods in the city earned nicknames such as "Little Hell" and "Satan's Mile."

The Black Hand and Sam Cardinella's gang called 'Il Diavolo' (The Devil) were the most dangerous in the city. The Black Hand relied on targeting business owners for payment at their own risk, though they were far less organized than future Chicago gangs. Cardinella's Devils was to thank for that, as his gang helped build the template for future gangsters in the city to follow.

By the time the 1919 World Series came around, gambling and baseball were as connected as peanuts and cracker jacks. According to Secret Base's parody article on the Black Sox Scandal, there were also allegations that there were at least five more World Series that might have been fixed — two of those being the 1917 World Series, which was won by Chicago, and 1918 World Series between the Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs.

While a comedy feature, the article does illustrate the fact that professional baseball had a gambling issue in the early 20th century, and Chicago was at the center of both pastimes.

The 1919 White Sox season and rising anger

After a disappointing 1918 that saw them drop below .500, the 1919 White Sox rebounded to an 88-win season and the AL pennant. And, like in previous years, the players were frustrated by Charles Comisky's cheapness. According to the University of Missouri-Kansas City, two of the team's stars, Shoeless Joe Jackson and third baseman Buck Weaver, made only $6,000 in salary. By comparison, according to SABR, the Detroit Tigers' star outfield Ty Cobb, a player who Jackson was compared to as his equal or close to his equal, was the highest-paid player at $20,000.

Aside from Jackson and Weaver, other players on the roster seemed to be underpaid based on their performances. Eddie Cicotte and Lefty Williams, the top two pitchers on Chicago, earned less than both Jackson and Weaver (Cicotte $5,000 and Williams $3,000). Cicotte had the most grievance in this regard as, according to Eliot Asinof's 1963 book, Eight Men Out, in 1917, Cicotte was allegedly promised a $10,000 bonus if he won 30 games. On pace to 30, Cicotte was benched for a few weeks and ended the season with 29 wins.

While this story has been contested, what has been accepted was Cicotte's financial troubles. Cicotte was the primary breadwinner of his family and had bought a farm in Michigan with high mortgage payments. All this anger finally boiled over when the World Series came around, and the players decided to make money they felt they had earned.

The fix is set

Anger and feeling unappreciated by their owner, the White Sox entered the 1919 World Series as heavy favorites against the Cincinnati Reds. However, unbeknownst to the public, players on the team had met with gangsters in Chicago to discuss the seemingly impossible: throwing the World Series. History reports that while baseball historians have debated the source of the fix, White Sox first baseman Chick Gandil and gambler Joseph "Sport" Sullivan had met weeks before the series to discuss preliminary plans.

Gandil said he was at first skeptical if an entire series could be thrown but was convinced and brought along some of his teammates. These were White Sox pitchers Eddie Cicotte and Claude "Lefty" Williams, shortstop Charles "Swede" Risberg, outfielders Oscar "Happy" Felsch and "Shoeless" Joe Jackson, infielder Fred McMullin, and third baseman Buck Weaver, though Weaver eventually pulled out and never accepted any money.

Interestingly enough, according to the New York Times, Charles Comiskey became aware of the plot following Game One, but without much evidence and not wishing to eat to the cost of exposing the players, Comiskey stayed quiet. Sportswriters and baseball officials suspected as well, because betting odds for the White Sox dropped considerably from an overwhelming favorite to an underdog right before the series. Gamblers knew Chicago was a bad pick.

After the fix was exposed the following season, the media attempted to portray the players as victims of gamblers and attempted to scapegoat immigrants and Jewish citizens as the true perpetrators.

The 1919 World Series

The White Sox clinched the AL pennant a week before the World Series. Between those seven days, Chicago's odds for winning the series went from 5-1 favors to 8-5 underdogs, according to Clear Buck. With their aces Eddie Cicotte and Lefty Williams both in on the plan, the White Sox immediately lost the first two games of a best-of-nine series (postwar interest led baseball to add an extra two games from the traditional best-of-seven). Cicotte began Game One by hitting the first batter he faced, indicating that the fix was in. The White Sox lost the game 9-1. In the next game, Lefty Williams walked six batters and the Cincinnati Reds took a commanding 2-0 series lead. Following the game, White Sox catcher Ray Schalk got into a confrontation with his pitcher in the locker room.

Still, with both games being in Cincinnati, it made sense for the Reds to take both games. And following a shutout by rookie Dickey Kerr, the Sox were only a game back from tying the series. However, the next two pitchers for Chicago was Cicotte and Williams, both of whom lost their games. Chicago won Game Six, again with Kerr on the mound, and then Cicotte won the next game to put the series at 4-3. In Game Eight, Williams once again took the mound and surrendered four hits and four runs in just five batters he faced before being pulled for another pitcher. Cincinnati rolled to a victory and World Series championship.

Reporters investigate the fix into the 1920 season

If gangster movies teach one anything, it is that schemes tend to go awry when people cannot keep their mouths shut. It might have been possible for the scheme to be hidden and fans look at the series as just a Reds' upset or the Sox's choking, but people in the fix started to drop hints to reporters covering the series. According to SABR, Chicago sportswriter Hugh Fullerton spoke to former pitcher and gambler Bill Burns, who was involved in the scheme on the eve of the series. Fullerton expected a Chicago victory, but Burns said with confidence the Reds were "a sure thing," creating suspicion for the writer.

According to Chicagology, Fullerton, in December of 1919, less than two months after the World Series, wrote in The New York World, "Big League Baseball Being Run For Gamblers, With Ballplayers in the Deal?"

ESPN's "Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame..." says that famed sportswriter Grantland Rice was told about the fix by a friend but remained silent. He was not the only one, as AL President Ban Johnson and former Chicago Cubs owner Charles Wegman heard that the series was fixed. Wegman did not believe that the series could be fixed, and Ban Johnson also dismissed the warnings.

The rumors and articles continued into the 1920 season. Chicago once again had a standout team, and in the final week of the season, it was battling for the pennant once again. Then the levees finally broke.

The fix is discovered and the trial

In September of 1920, a grand jury was convened to investigate allegations of gamblers in baseball. During the investigation, the previous year's World Series was investigated, and what was once unsubstantiated rumors became actual evidence. On September 28, Eddie Cicotte, Lefty Williams, Joe Jackson, and Happy Felsch confessed to a grand jury that they accepted money to throw the 1919 World Series. Charles Comiskey suspended the seven players on his roster (Chick Gandil was already suspended on a contract dispute) in the middle of a pennant race. The Cleveland Indians would win the AL pennant over the Sox.

According to Britannica, the trial of the eight White Sox players began in the summer of 1921. They were charged with conspiring to defraud the public, conspiring to defraud Sox pitcher Ray Schalk, conspiring to commit a confidence game, conspiring to injure the business of the AL, and conspiring to injure the business of Comiskey, as reported by Famous Trials. The prosecution's case immediately took a big hit when the grand jury confessions of the four players went missing. It is believed they were stolen.

While some players confessed or accepted the money, fan-favorite Buck Weaver, according to Clear Buck, met with Comiskey to proclaim his innocence and attempted to separate his trial from the rest. Jackson claimed he was tricked into the scheme, attempted to give back the $5,000, and his attorney took advantage of his illiteracy when he signed the confession.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis becomes baseball's first commissioner

As the eight players fought to stay out of jail, baseball sought to move past the scandal. Officials and owners in baseball feared that fans would lose faith in the game. To combat this, the AL and National League (NL) presidents agreed to name a commissioner of organized baseball in order to clean up the game.

They decided on one of the most respected judges in the country, Kenesaw Mountain Landis. According to Britannica, Landis' name first hit the spotlight in 1907 when he fined the Standard Oil Company more than $29 million for granting unlawful freight rebates. While the decision was overturned on appeals, Landis earned the reputation for being a people's judge and harsh against corruption.

Landis became a favorite in baseball when, in January 1915, a third professional baseball league called the Federal League fought the American and National leagues by filing suit claiming the leagues violated the Clayton Anti-Trust Act. According to SABR, the judge did not rule on the decision, even after the AL and NL ignored the Federal League's pleas of allowing their champion to compete in the 1915 World Series. Landis waited out the leagues and allowed a fair deal to be reached between the three. With this, Landis' reputation grew further as hero in baseball. So when it came time to find someone to clean the sport and regain the trust of fans, Landis was chosen as the commissioner on Nov. 12, 1920.

The verdict and Landis bans the eight players

On Aug. 2, 1921, after less than three hours of jury deliberation, the seven players and two of the gamblers were acquitted of all charges against them. The case of eighth player, Fred McMullin, did not go to trial, according to ESPN. Hundreds of fans cheered their heroes as they exited the courthouse as free men. And, in what had to be a moment of satisfaction for the players, owner Charles Comiskey was dismissed by the judge while testifying for being defensive and angering the judge, according to Encylopedia. The next day, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis dropped a metaphoric mountain on the heads of all eight men.

As the players celebrated the verdict, Landis issued this statement.

"Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ballgame; no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ballgame; no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are planned and discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball."

Just like that, the eight players were banned for life. Landis had done what he was brought into baseball to do — clean up the game by getting rid of anyone he felt was tainting it. Author and journalist Nick Acocella said of Landis that "he never really did an investigation. He just waited till the trial was over and suspended them for life."

The Legacy of the Black Sox

The eight players were the first of many who would be banned by Kenesaw Mountain Landis. He was put in the sport to clean up the game, and he had no issue with flexing his power. According to MLB, the same year he banned the Black Sox, he banned New York Giants outfielder Benny Kauff for theft and receiving stolen property. And the next year, he banned another Giants player, pitcher Phil Douglas, for suggesting leaving his team so they would lose the pennant. Landis would also suspend Babe Ruth and Bob Meusel for barnstorming without permission after the 1921 World Series.

After 24 years as commissioner, Landis died in 1944.

The reputation of Charles Comiskey, according to Britannica, was left tarnished for turning a blind eye to the fix. Also, despite having one of the largest team salaries in all of baseball in the 1919 season, Comiskey's cheapness is seen as the catalyst for the fix.

Seven of the dubbed "Black Sox" left the city and began new lives. However, Buck Weaver stayed in Chicago for the remainder of his life and filed for reinstatement multiple times. In 1989, the Black Sox's name came up when baseball's all-time hits leader, Pete Rose, was banned for gambling on games he played and managed in, according to History. Rose, like Shoeless Joe Jackson, would be a Hall of Famer if not for the banishment. The Black Sox legacy is the final moment for baseball's early days.