Animals Discovered Alive After We Thought They Were Extinct

Humanity is the only species that appreciates the sound of a distant ocean in a seashell, and marvels at the origami folds of flowers. Yet, for all our ability to absorb the impossible beauty this planet lays at our doorstep each day, we do a magnificent job of scrubbing it out like janitors would sneaker-scuffs in the gym. Our hustle and bustle has laid waste to millions of plant and animal species that may have held cures for cancer or just tasted good fried. Yet some remain, clinging to life like shipwreck survivors to a raft, and a precious few have even managed to return from the dead after they were believed to have gone extinct.

Some are big, some tiny, some can rotate their heads like Regan in The Exorcist, and others taste of urine and wax. Each of these supposedly extinct animals serves as a reminder that there is a lot of beauty and marvel worth fighting for on Earth, and that no matter the odds, there is always hope.

Coelacanths time-warp from the dinosaur age

To many, coelacanths are the poster children of species we thought were extinct. This Darwinian darling once again graced us with the knowledge of its presence off the coast of South Africa in 1938, a whopping 66 million years after it was thought to have retired. The initial find made headlines worldwide, and with good reason. The coelacanth is a biological time machine, giving scientists the chance to rewind to a time before humans even existed to examine what life was like when Earth was arguably crazier than it is now. Its morphology includes things that may have developed into humanoid features later on, like its uniquely hinged skull, tube-like heart shape, and a nearly vacant, fat-filled brain.

Despite a 400-million-year run, these bony fish are hanging on by a thread. There are less than 10,000 of the two species still in existence, with numbers continually dwindling. Nobody's trying to eat these chaps, but they're getting caught up in fishing nets, and are at risk from climate change.

While perhaps not likely to get a lot of Tinder matches, some might find the coelacanth's robust stature attractive, as they grow up to 6 feet in length, weigh up to 200 pounds, and live around 60 years in the wild. They're not very tasty, with oily, waxy, mucusy, and "uriney" flesh that lends a distinctly foul flavor to each bite. You're probably better off sticking to Brussels sprouts.

The world's biggest bee bumbles back from 'extinction'

This notoriously big bee uses a number of aliases to evade detection. Some know it as Wallace's giant bee. Others call it raja ofu, meaning "king of the bees" in Indonesian, as Indonesia is its only home. However, the official taxonomic classification is Megachile pluto, sounding more like a Smashmouth B-sides album than the name of a rare bee species.

Despite the fact that it's four times bigger than a normal honeybee, you might as well be walking on the Sun if you expect to find a specimen in the wild. Since its original discovery by Alfred Wallace in 1858, it's only been sighted a handful of times, eluding scientists until being rediscovered in 1981. Since then, the all-star species was feared extinct until two specimens popped up on Ebay in 2018, one of which sold for over $9,000. Its official rediscovery came in early 2019 after a five-day expedition, during which a single female was found in a termite nest, where the species typically burrows and nests, 8 feet off the ground.

If you're ever in Indonesia or on Ebay and think you've spotted one, check if it's as big as your thumb with incredibly large mandibles, and listen for its buzzing, which should sound like a low-powered electric razor. You may be looking at a female, which can grow up to 2.5 inches. Males only grow up to about an inch and lack mandibles. Typical males.

The return of the terror skink

This scream of a skink can only be found on the Isle of Pines. You know, that quaint French-owned islet south of Vanuatu claimed by France as part of New Caledonia?

The terror skink enjoys a shroud of vagueness matched only by the dinner plans of indecisive couples. A single specimen was collected by a French botanist around 1872 somewhere on New Caledonia, and the species was officially described some time after. It then proceeded to ghost humanity for over a century, leaving us to wonder about what could have been, and whether invasive rodent species annihilated it. Our concerns lasted until around 2004, when specimens started sliding into our DMs once more. "Hey," it said. "The rat population has dwindled. You up?"

Perhaps due to its terrible dating etiquette, not much is known about the terror skink beyond what we can learn from checking out its uniquely shaped bod. Long, sharp fangs curved like scimitars suggest that this skink has a taste for flesh that would put it near the top of the food chain among the island's highly diverse reptile population. This is unusual for skinks, as many species gravitate toward a more plant-based diet. The terror skink, however, has a reputation to uphold, choosing to sink its chompers into birds, eggs, or larger invertebrates like crabs, spiders, and other lizards.

You won't believe it's shrew

The Nelson's small-eared shrew would make a shrewd hide-and-seek player, as it has been found only twice in scientific history in a very specific hiding spot. The first time we laid eyes on this critter was in 1894, when two men named Edward traveled to southern Mexico and were able to collect a dozen specimens.

Edward Nelson and Edward Goldman simply had to climb 4,800 feet up the San Martín Tuxtla volcano in Veracruz to find them. The shrews were shipped to Washington D.C. to be classified before being stored away in drawers at the Smithsonian. Obviously, Nelson got all the credit. The species, which we could also call "Not Goldman's Shrew," would then skulk back behind the curtain of history for over a century before making a curtain call. Around 2003, a team of intrepid scientists spent four nights laying traps on the slopes of the volcano, eventually nabbing four more Nelsons. The shrew was the only mammal they caught, indicating that despite its limited numbers and endangered status, it's a hardy species capable of surviving a 1794 volcanic eruption that wiped out all vegetation around the volcano.

Considered one of the world's most endangered species due to its pickiness in living quarters, the sum of humanity's knowledge of this shrew amounts to little more than "sooty brown fur, about four inches long, and a larger, flatter skull than other shrews."

A rare petrel stationed in New Zealand

The New Zealand storm petrel was believed to be extinct for over 100 years before a chance sighting in January 2003, followed by photographic evidence later that year. Professional bird photographer Bryan Thomas happened to be on assignment off the coast of Little Barrier Island when he snapped the photos that would convince many that the nocturnal species was back from the dead.

The first true confirmation came in an odd fashion, when in 2005 a bird landed on a fishing boat in stormy weather. The fisherman, who just happened to be an ex-New Zealand Wildlife Service officer, quickly recognized the bird was distinctive and boxed it up.

Despite a renewed effort to study and track the species, the New Zealand storm petrel remains relatively aloof to scientists. It's small, about the size of a sparrow, and lives the majority of its life at sea, except for during sexy time. The New Zealand Herald describes a more recent breakthrough in the study of the species, when scientists were first able to track down a petrel nest and egg. Just about a square inch in size, it was described as "white with a fine dusting of pink spots concentrated on one end." A rather festive touch from this mysterious, definitely-not-extinct avian.

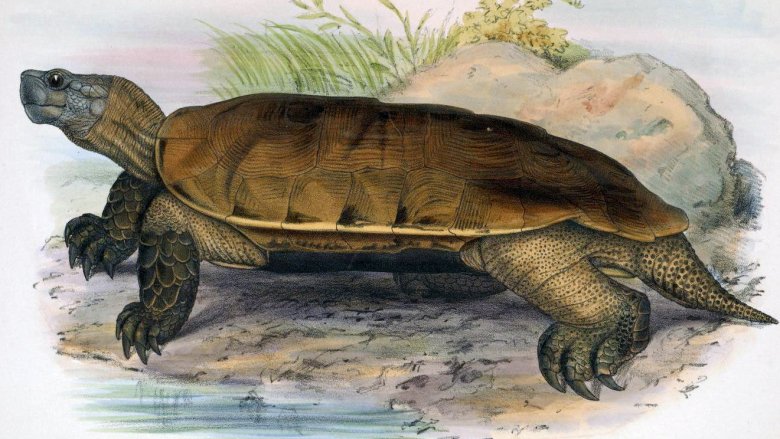

Turtle power in the Arakan forest

The Arakan forest turtle is an extremely rare breed, and one of the world's most endangered with only a handful in captivity and likely not many more in the forests of Myanmar and Bangladesh they call home. These lethargic loafers had been AWOL since a 1908 sighting by a British military officer, but then they started showing up in Asian food markets in 1994. While this specific breed was not commercially hunted, locals had no qualms about chowing down on them as "medical cures" for things like infertility, weakness, poverty, or lack of happiness. There are probably better ways to find happiness than eating turtles, but animal consumption for wellness is a widely practiced tradition deeply ingrained in some cultures.

While the hero in a half-shell just wants to hide in leaves and streams to eat worms and fish, the threat of human consumption coupled with a long mating cycle that produces just one egg per year has made the road to abundance increasingly difficult. Its inability to wield sword or bow staff has also proven critical to its lack of self-defense. However, recent years have seen conservation areas mandated, slightly increasing their numbers in the wild, and organizations such as the Turtle Conservancy and Zoo Atlanta have had success in hatching more, keeping the dream alive for these footlong shell-backed reptiles.

Tree lobsters refuse to go extinct

The Lord Howe stick insect was missing for quite some time, and lord how it was missed. Tree lobsters, as they're known colloquially, occur only in the Lord Howe Island Group, about 370 miles off the eastern coast of Australia. Once used as fishing bait, the population was thought to have been eradicated when the SS Makambo ran aground in 1918, introducing voracious black rats that resulted in the extinction of many of the island's animals. The problem got worse when officials tried to address it by introducing Tasmanian masked owls, a disastrous double-down on carnivorism.

Things took a surprising turn in 2001, when 24 of these surprisingly fast 5-inch bugs were rediscovered 100 feet up under a single Melaleuca shrub on Ball's Pyramid, a sea stack straight out of a fantasy novel.

Scientists were able to find two breeding pairs, one of which was sent to a private breeder, and the other to the Melbourne Zoo, which has since led to initial success in repopulating the species. By 2016, the zoo had hatched around 13,000 tree lobsters, and had also sent eggs to zoos in England, Toronto, and San Diego to establish insurance colonies. If all goes well, plans to repopulate Lord Howe island will be put into place once rat populations have been eradicated.

New Guinea highland wild dogs make a curtain call

The New Guinea highland wild dog is one of the most rare and primitive canine species in the world, and until 2016, was thought to have taken the high road and left the planet.

According to the New Guinea Highland Wild Dog Foundation, the first dog seen in over 50 years actually found us, following a researcher who was looking for evidence of the breed. Considered an apex predator of New Guinea, this species is known to natives as "Anging Penyani," or "dog that sings," and it is considered the foundational breed of what would become the rare but internet famous New Guinea singing dog, a genetic variant bred in captivity that is known for its unique and adorable vocal stylings. They howl with range matching Mariah Carey and Pavarotti, trilling and hitting notes that share sonic similarities with birds and humpback whales. The highland wild dogs are also related to Shiba Inus, giving the species even more memelord credibility.

The species is a variant of the gray wolf, diverging in evolution in the Late Pleistocene era, and also shares DNA with Australian dingos, giving you an idea just how much of an OG this canid is. Despite its proud lineage and confirmed sightings in the wild, virtually nothing is known about the species, which is considered something of a missing link in the genetic history of canines.

Return of 'extinct' parrot a caws for celebration

To many birdwatchers, the Australian night parrot is considered the Holy Grail. Finding it will rank you in rare company among ornithologists, perhaps netting you a sweet discount at your local Birdwatcher Supply store and the knowledge that you've laid eyes on one of the rarest birds in the world. The bird is so seldom seen that ornithologists who have spent decades searching for it haven't found it, or have risked their careers to photograph it.

This golden snitch of a bird was first described in 1861 by John Gould. From 1912 to 1979, nobody could find it, and since then it's only been seen a handful of times, including the most recent sighting in 2017 near Lake Disappointment.

Despite the mythical aura surrounding it, there's really not much to write home about when it comes to the night parrot. It's nocturnal, hence the name, and is essentially just a pudgy green ball mixed with bits of brown that prefers to hop around on the ground rather than use its wings. If you want to see it in flight, you've got to scare it, perhaps with a viewing of The Exorcist, which will cause it to emit its decidedly odd startled croak before lifting off. Otherwise it'll just putter around in tall grass scavenging for grass seeds and herbs.

The musk deer of Kashmir

Imagine being so seductive that people are willing to kill just for a chance to get a piece of you. This is the reality that the Kashmir musk deer must live with, playing the starring role in the animal kingdom's version of Fatal Attraction. Rediscovered in 2009 after disappearing since 1949, the deer species is native to Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, and India, where it makes its home in steep rocky outcrops with dense foliage, far away from screaming audiences and rabid fans.

Adding to its elusive nature, it's generally only spotted in early morning. With a soft, smooth, uber-pettable coat, the deer looks like it could make for a great plush doll to give to your niece for her birthday. Gazing into its big brown doe eyes, you just want to nuzzle your face right up to it and give it a big kiss ... until you see its fangs. Despite their otherwise cuddly appearance, males have razor sharp fangs used to do battle with other males during mating season.

It would be nice if they could also use them to maul poachers, who take them for their meat and seductive musky scent, traditionally believed to be an aphrodisiac. Capable of producing one of nature's most penetrating, lingering odors, the musk gland demand is so high that six of seven musk-producing species of deer are classified as endangered.

So good tarsier

Thought to have been extinct since 1921, the first glimmer of hope for the pygmy tarsier came in 2000, when scientists trapping rats in Indonesia accidentally trapped and killed one. While it wasn't an ideal start, a team managed to capture a few live ones eight years later on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.

Described as a cross between Gremlins and Furbies, these form sweet little couples which stay together for up to 15 months, spending their days lounging in trees and their nights hunting insects. At 4 inches long fully grown, and 2 ounces in weight, they are pocket-sized and undeniably adorable little carnivores, often preferring to communicate with one another through touch. Despite having the dimensions of a Kit-Kat bar, pygmy tarsiers pack a lot of unique features into their frames, ranging from cute to somewhat unnerving.

Each of their fingers has fingernails, and they love to use those glamorous fingers for communication. On the slightly creepier end of the spectrum, they can rotate their heads about 180 degrees both ways, an adaptation that helps their giant, fixed-socket eyeballs see insects to nibble. They also have some of the best night vision in the animal kingdom, meaning even when you can't see them, they can see you.

The adder we can't subtract

You won't find the Albany adder in New York, or almost anywhere else for that matter. One of the most threatened species still in existence, this South African snake has been recorded 12 times since its discovery in 1937. Actually, according to National Geographic, 13 times if you count the one they found that had been hit by a car, which would make a "snaker's dozen."

Tiny, venomous, and incredibly rare, it took a team of conservationists on an expedition weeks to find one, confirming the species still existed just one month before it would have been officially classified "extinct." They knew they had it when they spotted a 6-inch female slithering across a road, recognizing its bright patterning, constant look of surprise, and total lack of concern for automotive traffic.

This diminutive breed has never logged a human bite as far as anyone knows, preferring to seek out geckos, skinks, and small rodents. Nevertheless, though it's venom is presumed to be non-lethal and to maybe induce mild pain and swelling, the fact that it has venom at all makes the adder less likely to receive sympathy from the public. Combine that with a shrinking habitat and conservationists have their work cut out for them.