Strange And Mysterious Details You Might Not Know About The Terracotta Warriors

If folks unfamiliar with China recognize anything from the nation's history, it'd likely be the Great Wall followed by the Forbidden City with a dash of Terracotta Army thrown into the mix. But while the Forbidden City dates to the early 15th century and is actually a walled palace complex, the Great Wall and Terracotta Army go back much further — all the way to the third century B.C.E. Back then, Emperor Qin Shi Huang fused together pieces of previously built walls to form the one long mega-wall we know today. And before he died he started work on another colossal project that went unfinished: His own tomb and his ranks of terracotta warriors.

Emperor Qin Shi Huang came to power at the end of China's Warring States Period (481 B.C.E. to 221 B.C.E.), a long span of vies for territorial dominance that resulted in the Qin dynasty coming out on top. The regime fused China's seven states into one state government and oversaw the development of a standard writing system across the country, the building of roads and canals, and eventually the finalization of the Great Wall to delineate imperial rule. One of the Qin emperor's most impressive and puzzling projects set about building a massive tomb complex to carry his servants into the afterlife, full of infantry and cavalry, courtiers and government officers, entertainers and concubines, a replica landscape of local rivers, and more. Even now, though, about 2,000 years later, the complex and its famed Terracotta Army remain a mystery in many ways, and the structure is far from fully excavated.

Substitutes for human sacrifice

Out of all the questions about Emperor Qin Shi Huang's Terracotta Army, folks might be wondering why the emperor went through the trouble of commissioning thousands of clay warriors to begin with. After all, the mega-project took almost 40 years to get to its current unfinished point and employed an unbelievable 720,000 workers. The emperor had the means and resources to do so, however, and wanted to demonstrate his power and renown. But above all else, he essentially wanted to recreate his earthly empire in the afterlife: soldiers, horses, musicians, as well as acrobats, and even sexual partners. Though all the workers died during construction or were intentionally murdered to keep the site's secrets, the emperor at least used clay warriors rather than actual dead ones.

If Emperor Qin Shi Huang had followed traditions laid out by earlier Shang and Zhou dynasties he would have slaughtered real people for use in his tomb complex, including warriors, adjutants, enslaved, etc. The Penn Museum, for instance, describes specific Shang-era customs like laying sacrificial tomb occupants in a row and turning their heads toward an inner tomb chamber. Either out of a sense of sympathy or, more likely, not wanting to lose so many soldiers and other resources after unifying China, the emperor opted for sacrificial substitutes in the form of clay warriors. How he expected these warriors would animate and operate in the afterlife is unknown.

Hidden from the historical record

The discovery of the Terracotta Army would have come as an overwhelming shock. After all, the whole complex lay undisturbed, underground, and unknown for some 2,000 years before 1974. As the story goes, farmers at the time in Shaanxi, China were digging for wells during a drought. A few crossbow-wielding figures had been found in the region before then, but no one expected to stumble across a 20-square-mile tomb site containing some 8,000 total clay figures, a pyramid for Emperor Qin Shi Huang's actual burial location, remnants of stables, administrative buildings, a palace, and more.

It would be reasonable to expect that such an enormous project would produce an equally enormous written footprint in China's historical record. There are materials to purchase and transport, folks to oversee such purchases and workers, some way to organize the whole project and communicate about it over distance, and so forth. This is especially true because Qin rule — a short but highly influential era from 221 B.C.E. to 206 B.C.E. — gave China a unified and standardized written script. And yet, we have minimal written mentions of the Qin emperor's tomb and no explanations of the project itself. This could be because construction of the tomb complex was kept secret or because subsequent political unrest wiped such records out. We do have a Qin "mausoleum" mentioned during the Han dynasty (202 B.C.E, – 220 C.E.), but it doesn't include any specifics or references to terracotta warriors.

Warriors with unique faces

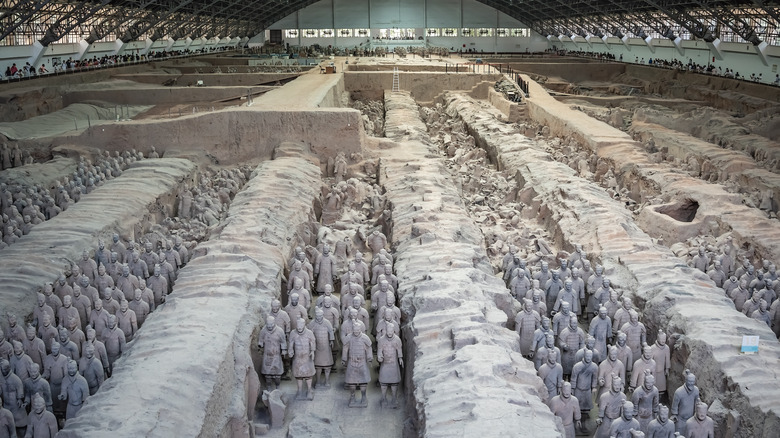

Looking at the endless rows of terracotta warriors at Emperor Qin Shi Huang's tomb from a distance, you'd be forgiven for thinking they're all the same diecast model. A closer look, though, reveals that each soldier has a different face and other adornments like hairstyles, hats, moustaches, shoes, ears, and so forth. That's 2,000 different faces excavated and restored so far out of a likely 8,000 total. While this is far less than the emperor's actual army of an estimated 500,000, it's more than enough to strain the limits of the production and artistry of the time. This is why it looks like some kind of early assembly-line production process is to thank for crafting the horde's base figures.

Chinese craftsmen used molds for certain parts of the warriors' bodies and then added layers of clay on top of them to make each figure distinct. Most of the warriors' hands, for instance, are identical and come from the same mold. The warriors' heads, meanwhile, come from eight separate molds. After craftsmen added each character's unique features, they lacquered each warrior to create a base for paint and then applied certain patterns and colors that indicated soldier ranks. These hues were typically bright, but of course have long-faded by now and left only small traces. Once a clay warrior was finished, it was fired and hardened into its final terracotta form.

[Featured image by thierrytutin via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 2.0 DEED]

Clay hands, bronze weapons

Even though the terracotta warriors were made from clay, their weapons weren't. Nowadays, visitors to Emperor Qin Shi Huang's tomb will see row upon row of weaponless warriors with their hands raised in a loose, fist-like posture, as if poised to grip something. That's because the warriors held actual bronze weapons at one point, like swords, axes, and spears. These weren't standard army weapons — they were made specifically for the emperor's tomb, and none of them showed signs of use in combat. In total, archaeologists have unearthed over 40,000 such weapons at the Terracotta Army dig site, which stayed well-preserved thanks to a particular chrome plating technique. Some weapons, however, were stolen by bandits in the years following the death of the emperor and subsequent collapse of Qin rule.

Archaeologists didn't just find a trove of bronze weapons — they unearthed bronze chariots, as well. Terracotta drivers mount these bronze chariots while bronze horses pull them. Other horses at the site are made from clay, like the warriors themselves. Much like the rest of the figures at the site, these cavalry sets were meant to imitate real components of Emperor Qin Shi Huang's army. On that note, in addition to military figures, the site also contains bronze birds surrounded by terracotta musicians playing instruments. It definitely seems like the emperor was hoping for a little rest and relaxation in the afterlife to go along with warfare and protection.

[Featured image by Difference engine via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED]

Rivers of flowing mercury

While Emperor Qin Shi Huang's tomb complex lay untouched for about 2,000 years, it's been open and available for archaeological work since its discovery in 1974. Yet researchers have excavated less than 1% of the whole complex. Yes, archaeology tends to work slowly to preserve historical artifacts, but given the popularity of the Terracotta Army, 1% still might seem strangely low. There's a sound reason for why work on the site has gone slowly: mercury.

First century B.C.E. Chinese historian Sima Qian — writing about a century after the Qin emperor's death — mentioned rivers of mercury in his tomb. It's the kind of claim that sounds hyperbolic or even absurd. But 2005 tests of the area revealed the strong presence of mercury, and it does look like the bottom of the tomb complex has channels dug into it in the shape of the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers. This is why excavation has gone extra slowly and cautiously on top of typical archaeological protocol regarding the preservation of historical relics.

On that note, those involved in the dig are concerned with honoring the past and not in a hurry to proceed. Smithsonian Magazine quotes former director of the Museum of Qin Terra-Cotta Warriors and Horses Wu Yongqi as saying, "I have a dream that one day science can develop so that we can tell what is here without disturbing the emperor, who has slept here for 2,000 years."