What It Was Like The Day Benito Mussolini Died

When it comes to World War II dictators, most people are probably going to think about Adolf Hitler — and for good reason, considering the terrible things he did. That said, Hitler was far from the only dictator causing trouble for the world at large; there's also Benito Mussolini, the closest thing to the father of fascism, to consider.

The leader of the Blackshirts movement — essentially the Italian fascist party — Mussolini rose to prominence through a combination of favorable circumstances (offering the people the comfort of order and stability in a time of turbulence) and sheer charisma, a factor that allowed him to keep power by building a cult of personality. Propaganda posters emblazoned with his face declared him "Il DUCE" (derived from the Latin for "chief" and, yes, written in capital letters) and made him appear almost superhumanly powerful.

But no amount of popularity could save him from persistent social problems. Or the fact he'd sided with Hitler. As World War II approached its end, Mussolini's own fame was his undoing, as he was recognized while trying to escape, then summarily executed on April 28, 1945. It was far from a pretty end for the Italian dictator — one that proved to be a cause of celebration for many, or a far-off world event for others, depending on circumstance. Here's a look at what was going on when Benito Mussolini died.

Mussolini reportedly died as a coward

Exact accounts of Benito Mussolini's death are something of a controversial topic, especially when it comes to specific details. However, most people do agree that he fled from Milan as it became clear the war wasn't favoring the Axis powers, heading north toward Switzerland. Despite a German Luftwaffe disguise, he was easily recognized, then taken to a small town near Lake Como. There, he was executed by machine gun fire, with communist partisan Walter Audisio claiming to be the executioner.

Whether or not Audisio fired those shots has become a matter of debate, but he did give quite the account of the incident. According to him, the execution wasn't the cleanest thing in the world — a machine gun and pistol both jammed before he got his hands on a different, working machine gun — but once those problems were ironed out, Audisio later boasted, "I had the impression of shooting not a man but an inferior being" (via The New York Times). He also went on to say that, in his eyes, at the very least, Mussolini died a coward. Per The Sydney Morning Herald, Mussolini spent his last day terribly anxious, and spent his last moments trying to bargain with his captors, reportedly even claiming, "Save my life and I will give you an empire." Obviously, those pleas — and those of his mistress, Claretta Petacci — fell on deaf ears, and apparently, his last words were cries of "No, no," directed at the men intent on killing him.

The people of Milan were ready to be rid of Mussolini

Despite the cult of personality that Benito Mussolini was able to cultivate in the early years of his rule, by the closing days of World War II, it should suffice to say that he wasn't experiencing quite the same level of popularity. Granted, the news of Mussolini's death didn't spread immediately, but the reactions given by the people of Milan tell enough of a story.

Before dawn on April 29, shortly after Mussolini's execution, his body was dumped into the then-infamous Piazzale Loreto, where fascists had displayed the bodies of dead partisans only eight months prior. Now, it was Mussolini's body — along with 14 other fascists and Claretta Petacci — out on display. And the public could make their rage known. As The New York Times put it (via the National WWII Museum), "The man who once boasted that he was going to restore the glories of ancient Rome is now a corpse in a public square in Milan, with a howling mob cursing and kicking and spitting on his remains." The angry mob beat Mussolini's dead body, threw food at it, and eventually took the corpses to a nearby gas station, where they could be strung up by their feet in a grotesque display. One woman even unveiled a pistol and fired at the body, yelling out, "Five shots for my five assassinated sons!" (via History).

The display only came to an end later that afternoon, when American soldiers collected the bodies and found Mussolini beaten beyond recognition.

Allied nations celebrated Mussolini's death

Honestly, it's probably not all that surprising to hear that people in Allied nations were pleased with the news that the infamous fascist leader of Italy was dead. It seems par for the course.

That said, media outlets did have something of a field day with presenting that news to the public. The New York Times came up with the bold headline, "A fitting end to a wretched life" (via The National WWII Museum), and Universal News opened their TV report on that day with the startling, all-caps declaration "MUSSOLINI EXECUTED." That same report then goes on with equally colorful language, exclaiming, "Bombastic Mussolini ... comes to his end in the gutter — a fitting climax to a life of treachery and double cross," before weaving together a quick story of how his grand dreams of conquest were ultimately ruined by allying with Adolf Hitler.

The string of startling news reports on Mussolini's death didn't necessarily end on that day, though. On the contrary, the next couple days were a flurry of activity for The New York Times, with a reporter so eager to transmit exclusive photos of Mussolini's body surrounded by people in the Piazzale Loreto that he drove 125 miles through a blizzard just to do so. And for seemingly good reason — the paper's night editor claimed, "I think that next to the Iwo Jima flag-raising, this is the second-best picture of the year."

Adolf Hitler was getting married

By late April 1945, the tides of World War II were swinging rather notably in favor of the Allied forces. Which does align quite well with the fact that Benito Mussolini was in the middle of fleeing his country when he was captured and executed. Bearing that in mind, it might sound a little weird that his ally, Adolf Hitler, was getting married on the exact same day that Mussolini was viciously gunned down, but the context might clear that up.

On the night of April 28, Hitler began dictating his will, having no intention of living long enough to witness defeat. In that will, he made mention of his longtime girlfriend, Eva Braun, whom he'd refused to marry in order to retain his female supporters: "After many years of true friendship [she] came ... of her own free will, in order to share my fate. She will go to her death with me at her own wish as my wife" (via The Washington Post). And in the middle of the night, that marriage happened. The wedding party itself only consisted of a few people, including a local registrar who was woken and shuttled to Hitler's bunker to conduct the ceremony, though he'd never even met the Führer. Both Hitler and Braun affirmed that they were of pure Aryan origin — a requirement for Nazi weddings — and the small group did hold a short celebration, complete with champagne.

Not that the marriage lasted long, though; they were both dead by suicide about 36 hours later.

One Nazi officer actually tried to surrender

The main trend you can see about this particular point in time is the fact it was rather clear that the Axis powers had no chance of winning the war. German and Italian officers could apparently see defeat on the horizon, and as a result of that, one Nazi official — Heinrich Himmler — actually tried to surrender to the Allies.

And Himmler wasn't some low-ranking officer in the Nazi hierarchy. On the contrary, he was actually the leader of the infamous SS and largely responsible for the formation of the Gestapo, otherwise known as the Nazi secret police. Beyond that, he's been heavily credited for the implementation of the "Final Solution," or the mass murder of European Jews. But after an assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler in mid-1944, Himmler began to consider peace treaties with the Western Allies, and a year later, in April 1945, he opened the door for negotiations (which ultimately fell through). But the situation became dire enough that on April 28 or 29, he reached out to the vice president of the Swedish Red Cross with an offer of surrender intended for the commander-in-chief of the Allied forces — future president Dwight D. Eisenhower. What exactly happened to that transmission is a bit murky, but at some point in those two days, Hitler got wind of Himmler's attempt to surrender. Not exactly pleased, he ordered that Himmler be arrested and stripped of his position, and Himmler himself tried to flee.

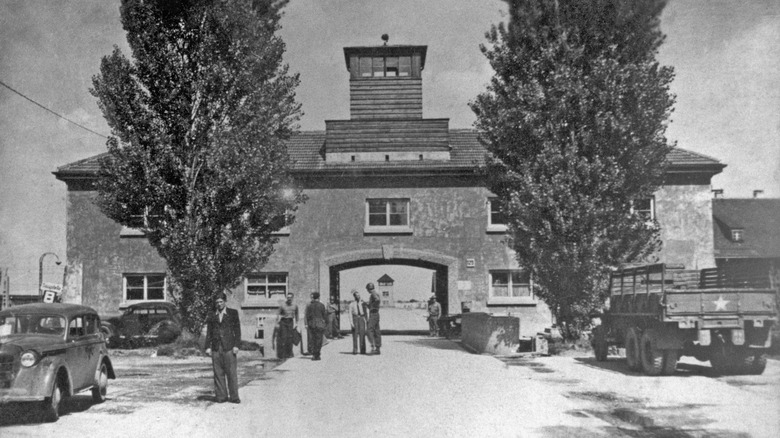

Conditions at Dachau deteriorated in horrific fashion

When it comes to Nazi concentration camps, Dachau comes in among the most infamous. Located just north of Munich, Dachau was the first regular concentration camp established in Germany, holding thousands of prisoners from 1933 to 1945, including prisoners of war, political prisoners, German Jews, and plenty of others ostracized for being different.

As the end of World War II loomed, the state of Dachau deteriorated as it was filled with prisoners transported from all around Germany, but also as rumors began to fly regarding the approach of Allied armies. They weren't all good rumors, though. As positive as liberation sounds, the reality was that many prisoners feared how the Nazis would react. Would they all be relocated — a move that could easily kill those in poor physical condition? Would they all be killed by SS officers, just so that they'd be denied freedom?

Those questions were warranted, because SS officers were, in fact, panicking. Leaders took to burning any and all documentation, forcing prisoners to help with the process, and even forbid anyone to move corpses to mass graves; in other words, bodies just piled up all around the camp. In fact, all the fears of the prisoners came true, as officers marched 7,000 of them to another concentration camp — a death march that probably killed about 1,000 people.

As Allied forces liberated camps throughout April 1945, they eventually arrived at Dachau on April 29, finally bringing a sense of relief to the inmates.

The public was processing the horrors of the Holocaust

Through the power of hindsight, most people today have a good grasp on the extent of the horrors inflicted during the Holocaust. At the time, though, the public at large didn't have the same level of understanding, and that didn't really change until late April 1945.

The numbers tell a pretty interesting story. While there had already been coverage of the atrocities committed by the Nazi party, a poll conducted in November 1944 showed that only about 76% of Americans believed there were any murders happening in those concentration camps. (Just for reference, that other 24% either didn't know what to think of the reports or believed they were entirely incorrect.) Of that 76%, under a quarter thought the death toll numbered over 1 million. In comparison, another poll conducted in May 1945 showed that over 90% believed the stories were true, and, on average, more people believed the death toll to be over 1 million.

A fairly notable shift, and one that might be attributed to events that also occurred in late April. As U.S. forces began liberating camps, American soldiers finally came face to face with the horrors of the Holocaust. That included Dwight D. Eisenhower, who requested on April 19 that members of Congress and journalists be taken to the camps for the express reason of showing the public what he had just seen. Journalists arrived over the next few days, and it likely didn't take much longer for the public to see those horrors themselves.

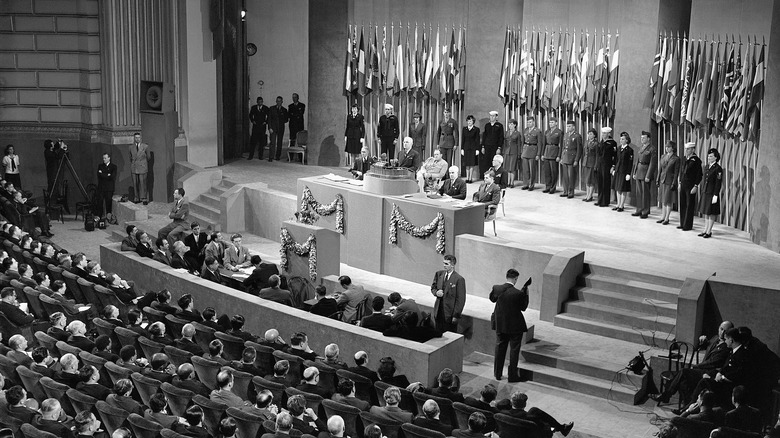

The United Nations was in the works

The idea of a worldwide peacekeeping organization was far from a new concept around the end of World War II. Rather, the idea had been around for a long time; the 1919 League of Nations isn't even the first example of that. And while it proved fairly ineffectual, those failures did provide an outline for a more successful organization.

The outbreak of World War II spawned a widespread desire for that successful peacekeeping organization, with many nations discussing just what that would look like. Various charters and negotiations took place during the war, and at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, leaders set an official date to charter a new entity: the United Nations. The starting time and place? April 25, 1945, in San Francisco, California.

So in late April, 850 delegates representing 50 different countries arrived at the San Francisco Conference (also known as the United Nations Conference on International Organization) with the goal of setting all the groundwork for the United Nations. Those talks included plenty of debate over how to use military power and a way to ensure equal influence for all nations, regardless of relative size. Said debates led to the creation of the Security Council (the executive body of the U.N.), a General Assembly in which all nations would be equally represented, and the International Court of Justice, meant to deal with international law. The Charter wouldn't be fully completed until June 25, but by April 28, delegates were already busy designing the U.N.

Soviet forces were devastating Berlin

For more context as to what was happening in Germany at the close of the war, then you need look no further than the Battle of Berlin. Generally considered the last major offensive of the European theater, the Battle of Berlin saw Soviet armies force their way into the city between April 20 and May 2. The conflict caused some 100,000 Soviet casualties, and an unrecorded number of German casualties. It is widely considered one of the deadliest battles of World War II.

But the truly devastating part of the battle doesn't come from the statistics. See, the Soviet army was racing to capture Berlin, and the feverish rush led to truly barbaric acts inflicted on the people of Berlin, whom the Soviets had stopped seeing as human beings. They brought tanks into the city streets and fired at buildings with little care for civilian casualties. Berliners hid in cellars, hoping to save themselves from the artillery, but that wasn't enough, as Soviet soldiers took to tossing grenades in, hoping to kill soldiers and not caring if civilians were caught in the crossfire. Some people tried hanging white flags in their windows, despite fearing reprisals from SS officials, and others desperately hoped that the Americans would arrive, if only to drive the Red Army away.

Then, there were the women of Berlin, who had further fears. While the first Soviet soldiers were, apparently, relatively professional, the same couldn't be said of later arrivals. A reported 100,000 Berlin women were raped, and stories have survived of them preparing to leap from windows just to get away.

The Bavarian Freedom Action

Late April 1945 was a busy point in time when it comes to World War II history; a lot of very important stuff happened right around the same time. And while a lot of those events have been well documented and committed to the collective memory, there's one event that's largely been forgotten: the Bavarian Freedom Action.

Here's the story: in Munich, a German commander named Rupprecht Gerngross began putting together a small resistance group known as Freiheitsaktion Bayern. Retaining only those loyal to the resistance — and sending away any ardent Nazi supporters — he worked with like-minded individuals to gather up a sizable store of weapons and form ties with a local militia. Then, on April 28, Gerngross and his rebels acted, taking over the local radio station and successfully transmitting a message, urging the people to fight back against the Nazis and wave white flags as a show of surrender to the approaching American forces. The message even reached Dachau, with escaped prisoners and other locals joining in on the rebellion.

Unfortunately, the effort was short lived, with SS officials from the Dachau concentration camp moving in to suppress the rebellion, killing a number of the resistance fighters. Nonetheless, this uprising is still considered one of the only successful ones carried out against the Nazi regime. Plus, it's largely credited with sparing the city of Munich (pictured) from complete destruction, as German forces decided against defending it through battle, allowing the American forces to arrive relatively unopposed.