What It Was Like The Day The Music Died

History is full of significant events that have come to define the day they happened on. However, it's easy to forget the grand scheme of things around such incidents. For instance, the day Martin Luther King Jr. died started civil disturbance all over the U.S., and news spread like wildfire on the day of Kobe Bryant's death, shocking fans and colleagues and prompting memorial events and gestures. It can be incredibly fascinating to look into the events surrounding such tragedies, since it provides so much more insight into the incident itself.

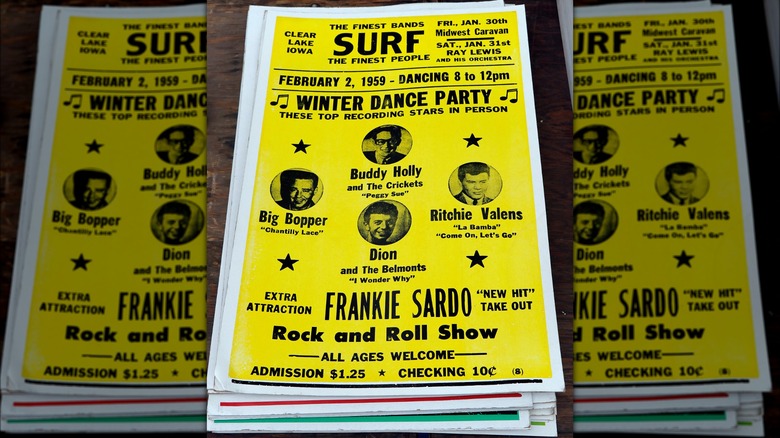

Consider one of the most tragic events in the early days of rock 'n' roll, known as "the Day the Music Died." On February 3, 1959, a plane crashed after taking off from Mason City, Iowa. The accident killed the pilot and the three rock stars aboard — Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. Richardson, aka the Big Bopper. Many people have heard of it, if only because it inspired Don McLean's famous 1971 hit song "American Pie," which was covered by Madonna in 2000.

But what led to the plane crash? How did Holly, Valens, and Richardson end up on the plane in the first place, and what was the world's immediate reaction to their passing? Did other significant events take place that day, only to be forgotten when this tragic accident grabbed a hold of this particular date in the zeitgeist? Let's take a look at what the Day the Music Died was really like.

The plane crashed almost instantly, but no one could reach it until the next day

Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper, and Ritchie Valens boarded a four-seat Beechcraft Bonanza plane piloted by Roger Peterson on February 3, 1959, shortly after their final show at Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa, had wrapped up at midnight. It was a true celebrity moment — rock stars stepping onto a private plane as adoring, hysterical fans looked on in admiration.

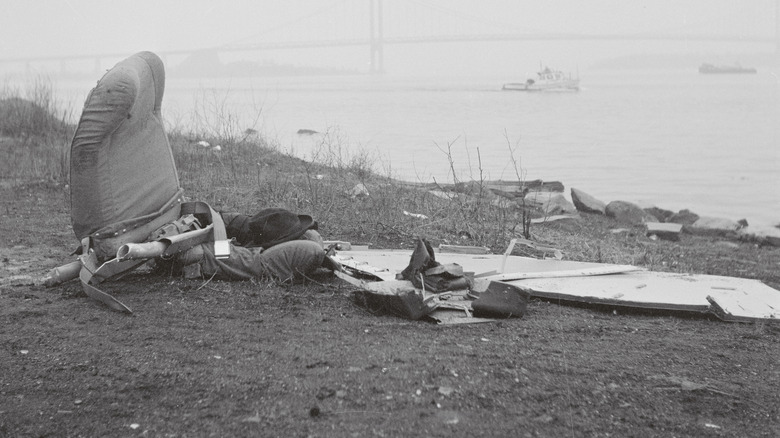

Unfortunately, things went wrong mere moments after the plane took off. After flying roughly five miles, witnesses saw the plane — or rather, its tail light, since the weather was very bad at the time and they were flying in a blizzard — suddenly start losing altitude. Peterson didn't answer radio contact anymore, and it was soon evident that the plane had crashed.

The Beechcraft Bonanza was traveling at 170 miles per hour when it hit the ground. Only Peterson remained inside the plane, as the impact and the ensuing flip were so powerful that all three musicians were thrown outside. What's more, the lack of light and extremely bad weather meant that there was no way for a rescue party to access the wreckage before morning, so the bodies had to lie in a field for hours. The tragic details in Holly's autopsy report reveal how violent the crash was. The impact split his skull, crushed his chest, and fractured numerous bones in his body, along with other extensive damage.

Buddy Holly was tired of the road and wanted to do everyone's laundry

Buddy Holly was on the Winter Dance Party tour largely because he needed money, and it was he who made the decision to fly to Minnesota (via Fargo, North Dakota) for their upcoming Minnesota show. The tour was a young man's game — Holly was 22 at the time of his death, the Big Bopper was 28, and Ritchie Valens only 17 years old — but even then, Holly felt the conditions on the road were too much. It was a bad winter, and the bus the tour was using was as cold as it was unreliable, having already broken down on the road. What's more, the distance between their February 2, 1959, concert in Iowa and their upcoming one in Minnesota was 400 miles.

The combination of the barely functioning tour bus and the long travel that lay ahead was unappealing for Holly, and the plane was his solution to avoid it. However, there were other reasons for the decision besides personal comfort. The musicians had been on the road for a while and were having an acute clean-clothes emergency, so Holly's intention was to take everyone's laundry with him and wash it while waiting for the bus travelers.

Waylon Jennings switched places with the Big Bopper at the last minute

In slightly different circumstances, the Big Bopper might have survived the February 3, 1959, accident — or rather, wouldn't have been a part of it at all. This is because he wasn't originally going to be on the plane. Buddy Holly intended to take his own two band members onboard, while the others were going to travel by bus. Bopper's place was originally meant to go to future country superstar Waylon Jennings, who played bass in Holly's band at the time. However, the "Chantilly Lace" singer was feeling under the weather, so Jennings decided to ride the bus to let Bopper in the plane instead.

This moment of kindness might have saved Jennings' life, but it also led to the tragic death of the Big Bopper. What's more, a haunting exchange Jennings had with Holly before the plane departed cast a dark shadow over his survival. "I hope your damned bus freezes up again," Holly joked to Jennings after hearing he'd given up his place in the plane (via the Independent). "Well, I hope your ol' plane crashes," Jennings replied.

Though he lived on and became a highly popular artist in his own right, Jennings' life story was tragic, and he had copious financial issues, health problems, and personal trouble. He also spent years haunted by his words to Holly, harboring survivor's guilt. Jennings died in 2002 at a comparatively young age of 64.

A coin toss sealed Ritchie Valens' fate

Ritchie Valens wasn't supposed to be on Buddy Holly's charter plane on February 3, 1959, but he really, really wanted to. The "La Bamba" singer's star was on the rise, and like everyone else, he was thoroughly fed up with the touring conditions. When he heard of Holly's plane and found out that it was already full, he started negotiating for Tommy Allsup's seat. Ultimately, Holly's guitar player agreed to settle the matter with a coin toss. Valens won and loved it. "That's the first time I've ever won anything in my life," he allegedly said before boarding the plane (via Far Out Magazine).

"[Valens] asked me four or five times could he fly in my place," Allsup described the fateful coin toss (via Rolling Stone). "For some reason, I pulled a half dollar out of my pocket and flipped it. He said 'heads' and it came up heads. So I went out to the station wagon and told Buddy. I said, 'I'm not going. Me and Ritchie flipped a coin. He's going in my place.' Buddy said, 'Cool.'"

Allsup went on to continue his music career after the crash as an artist and a producer, and died in 2017 at 85 years old. He understood how incredibly fortunate he was to avoid the plane crash, but like Waylon Jennings, he also struggled with guilt over the incident.

An investigation found the pilot at fault for the crash

Apart from the musicians, the pilot of the plane also died in the February 3, 1959, crash. Roger Peterson was 21 years old, and an investigation by the Civil Aeronautics Board eventually found that he was at fault for the crash. Per the investigators, he didn't have the necessary training to operate in such difficult conditions.

While there were no witnesses to the crash, the investigators found out that Peterson hadn't been accurately informed of the incoming bad weather, and when the snowstorm hit, he suddenly had to pilot the plane without being able to see anything. Since he wasn't able to fly using the plane's instruments alone and couldn't see the horizon, he may have gotten disoriented, which could have led to the crash.

In 2015, a pilot named L.J. Coon attempted to get the National Transportation Safety Board to reopen the investigation to potentially clear Peterson's name, citing passenger unrest, weight distribution issues, and other factors as potential contributors to the crash. "Roger would have flown out and about this airport at night, under multiple different conditions," Coon commented to the Pilot Tribune (via The Guardian). "He had to be very familiar with all directions of this airport in and out." However, the board decided that Coon's input didn't warrant further investigation.

The other tour members didn't find out about the crash until they arrived in Minnesota

In 1959, lines of communication were very different than they are now. There were no mobile phones or internet, so when a group of people were on the road in a freezing bus, they were effectively isolated from the rest of the world. As such, the Winter Dance Party tour members who weren't in the plane didn't actually find out about the tragedy before they were already in Minnesota for their gig later that day, and started wondering where Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper were.

Holly's family members also heard of the crash in a rather unnerving way. The pregnant María Elena Holly was waiting for her musician husband to call her from the road when she found out about the news from television. The traumatic moment has been blamed for her miscarriage shortly after learning of Holly's death. Likewise, Holly's mother utterly broke down when she heard about her son's death on the radio.

The crash prompted a major change in the way authorities handle tragedies

The plane crash that killed Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper also had a surprisingly profound impact on the way such tragedies are reported these days. Holly's next-of-kin, in particular, found out about his death from the media, to their vast horror and grief.

This obviously isn't an ideal way to learn about a loved one's death, and it had some pretty horrific consequences. Holly's wife María Elena Holly, in particular, was pregnant at the time and reportedly lost the baby because of the shock.

Authorities recognized that something had to be done to avoid similar tragedies in the future. As such, airline and media organizations soon began adhering to a new policy: Going forward, the victims' families would have to be notified before making their names public. Administrative wheels turn slow, so this didn't happen until some time after the crash. Still, the origins of the policy very much tie into the events of February 3, 1959.

The Winter Dance Party was a nightmare that went on even after the crash

One thing you might assume to have happened the second the world learned of the plane crash actually didn't take place. In spite of losing three of its popular stars, the Winter Dance Party tour wasn't cancelled, and ended up continuing with a lineup that had been slightly altered for obvious and tragic reasons.

The tour's abysmal traveling and living conditions were a large part of what inspired Buddy Holly to hire the fateful plane in the first place. The combination of long distances between venues, a cruel winter, and a sub-par tour bus was punishing. In fact, Holly's drummer Carl Bunch actually ended up in the hospital after getting frostbite on both of his feet.

What's more, the tour continued even after the February 3 tragedy. Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper weren't the only acts on the roster — the lineup also included Frankie Sardo and Dion and the Belmonts. As such, the remaining musicians had to wrap up the Winter Dance Party tour with a truncated lineup where Waylon Jennings performed vocals during the Buddy Holly set, with other teen-favorite performers such as Frankie Avalon and Fabian flying in to round out the bill. The surviving musicians had to play a concert at the Armory in Moorhead, Minnesota, on the same day the plane crashed, and went on to play a total of 13 venues in as many days.

Buddy Holly had a gun on the plane, which led to the Big Bopper's autopsy in 2007

The most notable events around a particularly strange rumor about February 3, 1959, didn't happen on that day, but the plane crash nevertheless marked the start of a strange sequence of events that ended with the autopsy of J.P. "The Big Bopper" Richardson ... in 2007. Some two months after the crash, it was discovered that Buddy Holly had carried a gun on the plane. Because of this and the sudden nature of the crash, rumors started circulating that there had been gunfire in the plane and pilot Roger Peterson had been shot. People also kept raising their eyebrows over the fact that the Big Bopper's body was found farther away from the plane than the others. This caused some to wonder if he had somehow survived the crash and managed to free himself from the wreckage before succumbing to his injuries.

In 2007, the Big Bopper's son, Jay Richardson, had finally had enough of the whispering. He commissioned forensic anthropologist Dr. Bill Bass to examine his father's body to find out whether there was anything truth to the rumors of his father still moving on his own accord after the crash — or taking a bullet, for that matter. Bass' findings were conclusive on both fronts. "There was no indication of foul play," he told CBC. "There are fractures from head to toe. Massive fractures ... [He] died immediately."

There was another, much worse plane crash that day

The Day the Music Died is etched in memories as the date of Buddy Holly's, Ritchie Valens', and the Big Bopper's deaths. However, there was also another plane crash on February 3, 1959 ... and it was a much worse one when it comes to sheer loss of human life. At 11:56 p.m., American Airlines Flight 320 from Chicago to New York City was approaching the La Guardia Airport when the plane flew too low and crashed on the East River before hitting the runway. The accident happened because of a combination of bad weather, the crew's inexperience with the Lockheed L-188 Electra plane type, and altimeter issues.

Because of darkness, heavy wind and rain, and the fast-moving river, locating survivors was difficult, and rescuers were only able to save eight people from the wreckage. Sixty-five people died.

While it wasn't one of the deadliest plane crashes in history, the American Airlines Flight 320 crash is objectively on a completely different scale than the crash of the musicians' four-seater plane. However, due to the latter crash's cultural relevance, it's not hard to guess which one is easier to find if you google plane crashes that happened on this particular day in history.

The Day the Music Died overshadowed another notable death

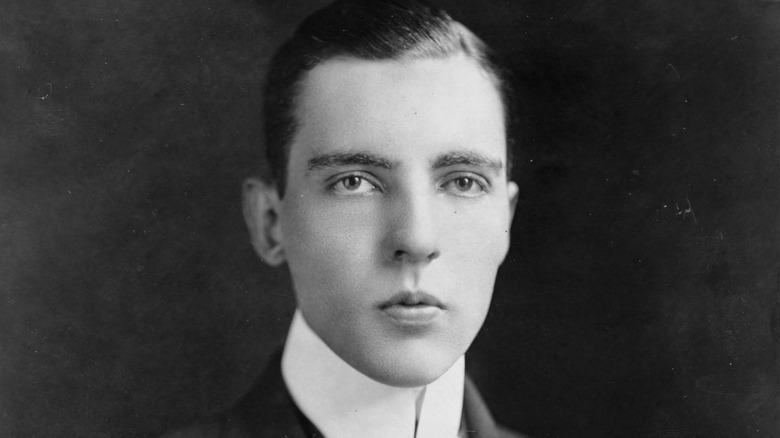

February 3, 1959, saw more than its fair share of tragedy, though not all of it was as dramatic as the deaths of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper or the American Airlines Flight 320 plane crash. This was also the day Vincent Astor died of a heart attack, aged 67.

While the name might not ring a bell, Astor's status and achievements might. Vincent Astor was part of the Astor family, who were the very first millionaires in the United States, and massive movers and shakers in New York City's more powerful circles. Former prominent family members include John Jacob Astor and William Backhouse Astor, who built the family's fortunes to around $50 million circa 1875 — well over $1.4 billion, adjusted for inflation. Other members of the family have been involved in politics, inventions, and writing, though the family's financial backbone has long been real estate.

Vincent Astor kept his eye on the ball when it came to real estate and other business, but he was also a notable philanthropist who supported various social reforms, created the Vincent Astor Foundation to award grants to do-gooder institutions, and gave several good real estate deals for the city's housing projects. His passing on the Day the Music Died kicked off the next phase in the family's story ... which unfortunately started with a fight over his will between his wife and his half-brother.