The Untold Truth Of Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman's exalted place in American history is inarguable and unparalleled. In the span of just 11 years, Tubman helped roughly 70 men, women, and children escape the southern slave states for free lives in the North, becoming the most accomplished conductor on the so-called Underground Railroad. Even when her own freedom was secure, she never took her eye off the prize, returning again and again to the pro-slavery South to free African-Americans from bondage. She also served as a Union spy in the Civil War, was active in the women's suffrage movement, and even dedicated her later years to caring for the elderly and indigent.

Born Araminta Ross in Dorchester County, Maryland, in the early 1820s, Tubman is one of those historical figures, like Abraham Lincoln or Frederick Douglass, who really needs no introduction. That said, her reputation as a unique American heroine has experienced a resurgence, partially in response to an effort to put her face on the $20 bill — a move that has apparently been postponed until 2030. And no one deserves the attention more. As Tubman said at a 1896 suffrage convention, "I was conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can't say — I never ran my train off the track, and I never lost a passenger." But let's dig a little bit deeper into this American icon and find out the untold truth of Harriet Tubman.

Harriet Tubman was inspired by her mother

Southern slave owners regularly separated children from their parents, profiting handsomely from what, in effect, amounted to organized and state-sanctioned kidnapping. Harriet Tubman's family was no exception to this rule.

Born to Harriet "Rit" Green and Ben Ross sometime near 1820 on a Maryland plantation owned by the Brodess family, Tubman was one of nine children, and in the course of her turbulent and often violent childhood, three of her sisters were sold off to faraway plantations by the slave owner, Edward Brodess.

When Brodess informed Tubman's mother that her youngest child, Moses, was soon to be sold to a plantation owner in Georgia, Rit refused to cooperate. She fought Brodess off so bravely that he eventually had no choice but to give in and allow mother and son to remain together.

Tubman, who was often beaten by Brodess and other white authority figures on the plantation, witnessed her mother's courageous battle and was inspired by it. In 1849, having married a free man named John Tubman, Harriet (who went by the name "Minty" at the time) decided to escape to Philadelphia. Her brothers joined her on the perilous journey, but they lost their nerve when they saw a newspaper ad offering $300 for their recovery. Tubman accompanied her brothers safely back to Maryland, but having tasted freedom, she wanted nothing less. She followed the North Star and the Underground Railroad to Pennsylvania on her own.

Tubman's head injury impacted her life

As a young girl, Tubman suffered a head injury that would continue to impact her physical and mental health until her death. She received the injury when an enraged slave owner threw a two-pound weight at the head of another slave who'd attempted an escape. Tubman was struck instead and soon after began experiencing bouts of dizziness and pain. She was also prone to seizures and excessive sleepiness. The latter condition, also called "hypersomnia," prompted some people to mistakenly label her lazy. In fact, it was almost certainly a result of that fateful head injury.

It's more difficult to say if Tubman's vivid dreams or her strange visions, which included regular visits from and chats with God, were likewise a result of the same injury, but she was always quick to credit her deep Christian faith with giving her the courage she needed to continually put herself in harm's way for the betterment of others. She was also known to approach her friends for much-needed funds for her trips south, claiming that God sent her. She was rarely refused.

Because she was completely confident that God was on her side and that death would only bring her eternal life, she feared no one and nothing. For Tubman, a slave owner with a gun and a pack of dogs was no match for the divine power of her heavenly Father.

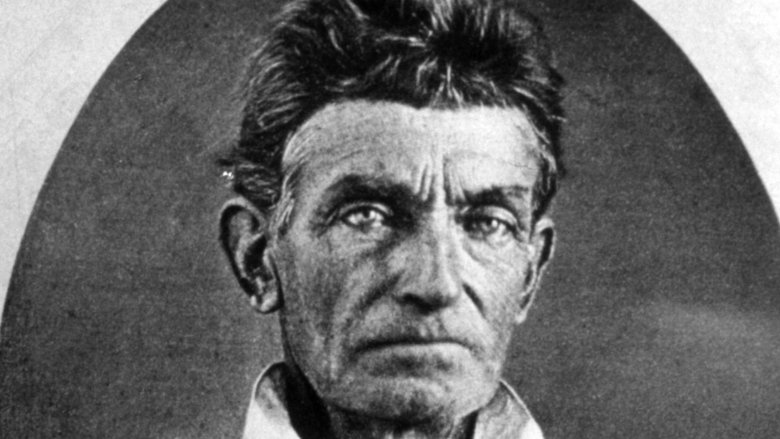

She was buddies with John Brown

Tubman was well-respected and revered by the abolitionist community, whose members considered her not just an ally but a leader and an inspiration. John Brown, who became famous for the botched raid at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, even went so far as to call her "General Tubman."

The raid, which took place on October 16, 1859, was intended to be a crucial strike against slavery. Brown hoped that by recruiting a number of young men to his cause and sneaking into the industrialized Virginia town, he might not only be able to capture the town's ammunition stores but ignite a rebellion. Even though the raid itself didn't go as planned, Brown did by many measures succeed. His willingness to take up arms in defense of human rights, as well as his martyr's death by hanging, drew attention to the abolitionist cause and lit a fire under Americans on both sides of the debate. It probably also helped elect Abraham Lincoln, whose candidacy, prior to the Harpers Ferry raid, seemed destined to fail.

Tubman was quick to champion Brown, whom she described as the best white man who'd ever lived. She even had a prophetic vision of him prior to their meeting. Like Tubman, Brown considered himself a soldier in God's army. In 1856, he told his son, Jason, "I have only a short time to live — only one death to die, and I will die fighting for this cause."

Harriet Tubman and the Combahee River Raid

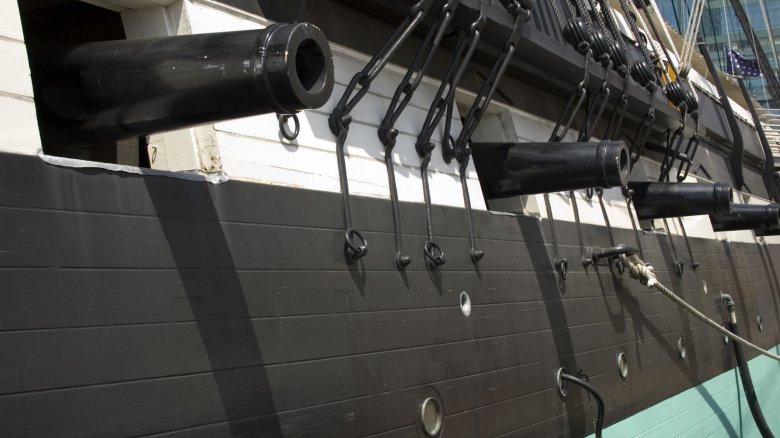

On her own, Tubman freed at least 70 slaves. With the help of Union soldiers, that number increased a hundred fold in one day. In June 1863, Tubman, along with the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers (an infantry regiment of free blacks) and the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, boarded three Navy gunboats in the dark of night, and under the leadership of Colonel James Montgomery, headed up South Carolina's Combahee River with the intention of disabling Confederate river mines, as well as destroying key supply centers in the area. Thanks to Tubman, the operation's main scout, the raid came off without a hitch.

Perhaps most damaging to the Confederate side was the sight of 756 slaves abandoning their posts in the middle of the raid and joining Tubman, Montgomery, and the two regiments on their ships. The men and women fled in such great numbers that their white owners could do nothing but stand by helplessly and watch.

According to Tubman, many slaves grabbed whatever they could on their way to the ship, including pigs, pears, and steaming rice pots. Tubman and Montgomery laughed with joy at the scene. Later, the majority of the newly freed men joined the Union ranks, and Tubman added "first woman to lead a successful raid in the Civil War" to her already impressive list of accomplishments.

She believed in the power of prayer

Tubman was a deeply devout Christian, and she prayed constantly, both as a slave and as a free woman. She even claimed that God visited her at least once a day, and during such visits, he often instructed her to borrow money from her friends in order to fund her difficult journeys south to free members of her family and other slaves hungering for a new life.

Prior to her escape from slavery and when it appeared her owner, Edward Brodess, might sell her because she was often sickly, she first prayed he would change his ways and free her. Then, when Brodess only continued to be a cruel and heartless man, she prayed he would die. Shortly thereafter, he did die of an apparent heart attack, making Tubman worry about her own power and intentions. She even wished retroactively that she could continue to pray for Brodess' soul.

Brodess' will stipulated that all of the slaves on the plantation would, at the very least, not be sold out of the state of Maryland. Most of Tubman's fellow slaves seemed either happy with this arrangement or resigned to their fate, but she never stopped longing for freedom, and eventually she got it, very much convinced that God and prayer helped get her there. When she did finally reach the North, she changed her name from Araminta to Harriet, most likely to honor both her mother and a sister who was sold away from the family.

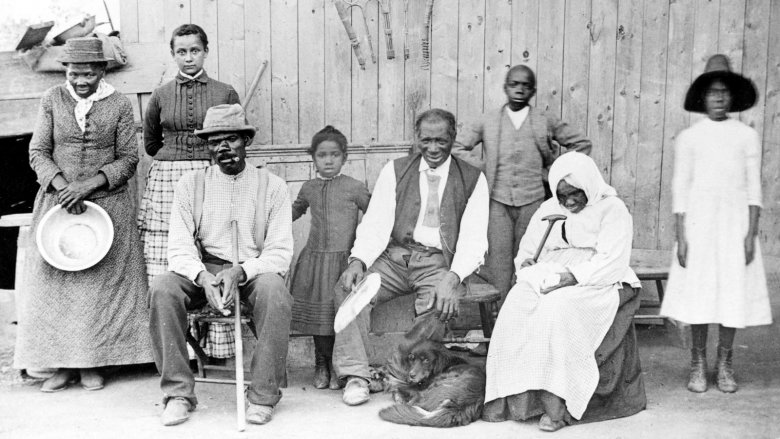

Fighting for her family

While she was still a slave, Harriet Tubman — then referred by her birth name, Araminta Ross — married a free man named John Tubman. Not much is known about him beyond the fact that he seemed to view Tubman's longing for freedom as unrealistic and naive. He laughed at her dreams, both the sleeping and waking ones, and according to Tubman's first biographer, Sarah Hopkins Bradford, he even helped slave catchers try to find her and bring her back to servitude. In 1849, five years after their wedding, he refused to join Tubman when she finally left enslaved Maryland for free Pennsylvania.

Many of the trips Tubman took back to the pro-slavery South were for her family, and by the time slavery was outlawed, she'd succeeded in bringing almost all to safety, including her mother and father. Tubman returned at least once to attempt to convince John Tubman to join her in Philadelphia, but by that time, he'd remarried and was even less interested in her efforts than before. That didn't stop Tubman from fashioning a family of her own. In 1869, 20 years after she became free, Tubman married a Civil War veteran named Nelson Davis, and together they adopted a daughter, Gertie, in 1874.

Harriet Tubman knew how to game the system

Tubman took a little under 20 trips south to help fugitive slaves escape to freedom, and every excursion was a resounding success. No one was injured, and no one was lost. This was due in part, of course, to the brilliant and clandestine workings of the Underground Railroad, but much of the credit goes to Tubman as well. You don't get that kind of track record without doing your homework, and Tubman was not only fearless but cunning. She made sure to always began her trips in the winter, when most people would be shut up inside and not on the lookout for slaves, and she was also careful to arrive at plantations on a Saturday night. Given that slaves often had Sundays off, this all but guaranteed their masters wouldn't notice their absence until Monday morning. Missing and fugitive slave notices wouldn't appear in newspapers until Tubman and fellow travelers were well on their way, throwing slave catchers and their ruthless teams of dogs and vigilantes off the trail.

Other methods Tubman used to increase the chance of a trip's success included taking the master's horse (thereby limiting his ability to come after them), sedating babies so they wouldn't cry and alert slave owners to the escape, and remaining armed at all times so that, in the event a fugitive grew unsure about the journey, she had the power to convince them to stay the course.

Tubman's Canada connection

In 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law, stipulating that slaves caught in the North had to be returned to the South where they would again be enslaved. Tubman had been accustomed to ending her journeys in Philadelphia. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, though, stopping in New England was no longer a viable option, and she took it upon herself to reroute the railroad all the way into Canada, where slavery was outlawed and the legislation couldn't reach.

She settled on the town of St. Catharines, Ontario, as her final destination because it was an abolitionist stronghold. She and her family soon made a peaceful life for themselves there, joining the Salem Chapel, an Episcopal church run by African-Americans, and participating in local community life, until the breakout of the Civil War effectively put an end to the Fugitive Slave Law.

Tubman left Canada to become a spy and for the Union side. Thereafter, Tubman and her family lived in Auburn, New York, where she cared for her elderly parents until their deaths.

She fell victim to a conman

Harriet Tubman was undoubtedly brilliant, but even she at times let her guard down, usually when she was trying to help a family member or the less fortunate. And in 1873, she fell victim to a scam that took in countless New Englanders hoping to make an easy buck.

The scam was perpetrated by a charming African-American man who went by a number of aliases, including Stevenson, Johnson, and Harris. The man's modus operandi went a little like this: He traveled to a small town, found a trusted citizen, and told that citizen that he'd recently discovered a trunk of Confederate gold bars buried in an undisclosed location above the Mason-Dixon line. Then the conman got the aforementioned trusted citizen to appeal to his friends and family, asking them to invest in the scheme. The trickster got to Tubman through her brother, John Stewart, who was sure that, between all of his sister's connections in the village of St. Catharines, Ontario, they would for sure be able to raise the $2,000 the conman was demanding as a buy-in.

Tubman eventually raised the funds and headed out into the countryside with the conman and his cronies to find the trunk. The men led her to a spot of woods where a box sat waiting. Tubman demanded to see the contents of the box before she would hand over the cash. The men beat her, tied her to a post, and took the money, leaving her injured and humiliated.

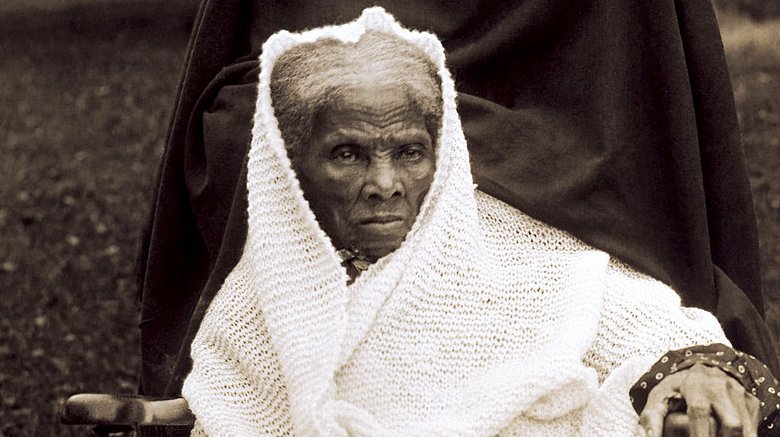

Tubman wasn't big into retirement

You might think that someone who managed to bring roughly 70 slaves to freedom (not counting the 756 she helped liberate as part of a Civil War raid on Confederate forces in South Carolina) would spend her twilight years with her feet up, contemplating her legacy and resting on her laurels. Not so with Harriet Tubman, who at the end of her life added elder care to her long list of passions and causes, which already included abolitionism and women's suffrage.

At age 74, Tubman, who'd gone from being a conductor on the Underground Railroad to a caretaker of her elderly parents, purchased a 25-acre tract of land in Auburn, New York, in order to build what would become the Tubman Home for Aged and Indigent Negroes. She bought the land in 1896, and with the help of the African Episcopal Methodist Zion Church, she saw it begin housing and treating patients in 1908.

Five years later, Tubman died there herself in a room named after John Brown.

Harriet Tubman's biblical nickname

Tubman was nicknamed "Moses" thanks to her efforts to free her people from slavery. Like the biblical figure, Tubman's life's work was bringing men, women, and children to freedom. And the nickname did double-duty. It not only honored her courage and selflessness in the face of danger, it also helped shroud her identity while she guided slaves through the Underground Railroad. Slave catchers might get word that a person named Moses was hard at work, helping fugitive slaves escape, but they might not put two and two together to realize that Moses was indeed Harriet Tubman.

Song played a large part in her work. Slaves signaled to each other that Tubman was on her way by singing old time spirituals like "Steal Away," "Go Down, Moses," and "I Looked Over Jordan." The hymns spread like a fire from field to field, plantation to plantation, alerting people to the fact that it was time to prepare for the journey. And many historians believe that it was Tubman who inspired the classic hymn, "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot."

So what if she didn't part an ocean? She certainly moved mountains.

The mystery of Margaret

In 1859, Tubman made a journey to Maryland to pick up Margaret, a girl she claimed was her niece but whom some historians believe was actually Tubman's daughter. According to the biography Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom by Catherine Clinton, Tubman's decision to retrieve Margaret was not in line with many of her other rescue attempts. For one thing, when Tubman came for the light-skinned girl, Margaret was apparently living the comfortable life of a free young woman. Why would Tubman make such a point of freeing someone who was, for all intents and purposes, already free? Margaret seemed to wonder that same thing. She sometimes described Tubman's actions as "kidnapping."

Margaret also had a twin brother who was living with her at the time of Tubman's arrival. It's odd that the notoriously meticulous Tubman would make no attempt to free the boy as well. Margaret's daughter, Alice, later said that Tubman realized that her taking Margaret away from the only home she'd ever known was wrong, but that Tubman wanted very much to mother the girl. Alice even went so far as to suggest that Margaret might've been Tubman's biological daughter, noting a resemblance between the two women.