What Pre-American Hawaii Was Really Like

To many Americans living on the continent and to tourists around the world, Hawaii is first and foremost a popular and perennial vacation destination. The state's eight major islands lure thousands of people each year with the promise of gorgeous, sprawling beaches, endless luaus, coral reefs teeming with wildlife, and the many rewards of the so-called aloha lifestyle.

But before it was tourist haven, before it had bragging rights as birthplace of Barack Obama, before it was declared America's 50th state, Hawaii was a wild and unspoiled volcanic archipelago that managed to remain wild and unspoiled for millions of years, largely because the islands are located nearly 2,000 miles from the nearest continent. According to HawaiiHistory.org, the first Hawaiian islands began arising from the depths of the Pacific Ocean roughly 30 million years ago, a result of the Pacific Plate moving in a northwesterly direction over a hot spot at the breakneck speed of 32 miles per million years.

It wasn't until Polynesian sailors came upon the islands that Hawaii saw its first human inhabitant, and it would take several hundred more years for the Western world to catch on. By the time it did, Hawaiians were a proud people with strong traditions, intricate systems of governance, and a language and culture all their own. What was pre-American Hawaii really like? To find out, read on.

A race of little people

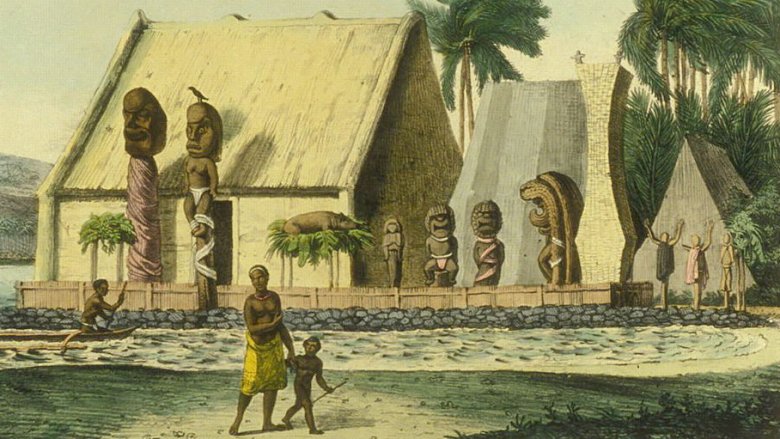

According to legend, the Hawaiians who inhabited the island prior to the Polynesians were a race of little people who, despite their small stature, were incredibly productive. When the Polynesians first arrived in Hawaii — somewhere between 1 and 600 AD — they found evidence that someone had been there before them. Such evidence, according to Ancient Origins, consisted of temples, roads, dams, and fish ponds, some of which can still be seen today.

Folklore suggests that these ancient men and women were so exacting that if a project they'd started in the morning wasn't finished by nightfall, they would abandon it entirely.

Many scholars believe that Hawaii's earliest human inhabitants came from the Marquesas Islands, and that they were the craftspeople behind the island's most storied and impressive ruins. One such theory posits that the Tahitians, who arrived in Hawaii around 1000 AD, weren't impressed by the islands' native populace, slapping their predecessors with the insulting nickname the "manahune," which means "the lowly people" or "people of low social status." Allegedly, that scorned race moved from the lowlands to the mountains. An 1820 census even lists 65 members of the tribe.

Over time, the spelling of the term "manahune" has morphed, and so has its meaning. Today, "menehune" now refers to a race of tiny perfectionists who live deep in the islands' forests, out of sight of human eyes.

Pre-American Hawaii was colonized by ancient seafarers

Hawaii's first known inhabitants were Polynesians, who discovered the volcanic chain sometime before 600 AD, and over the course of generations, began colonizing the place. This was no small feat, the discovering or the colonizing. The Polynesians who stumbled on Hawaii had, according to Lonely Planet, most likely come from thousands of miles away, and they did so without the help of compasses, metal, wheels, or clay.

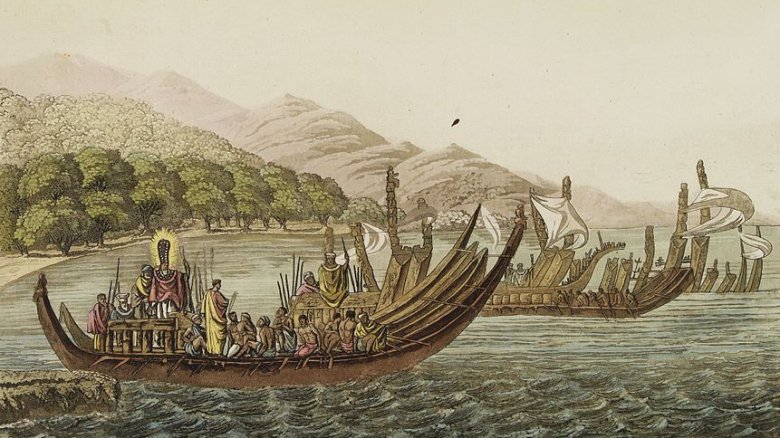

According to PBS, they crowded into 50-feet-long double-hulled canoes and sailed with the help of the stars and by closely observing ocean swells and bird flight paths. The second wave of colonizers arrived around 1000 AD, and they hailed from Tahiti, 2,400 miles from Hawaii as the crow flies. The Tahitians reportedly subdued the already settled populace and conquered the islands for themselves, giving rise to what would become a rigid class system and a relatively sophisticated form of government in which the ali'i, or chief class, reigned supreme, and the mokupuni, or regular people, had to do their bidding.

The Polynesians stopped arriving in Hawaii around 1300 AD. In fact, they stopped taking long, oceanic voyages entirely. The reason for this cessation has long been a mystery, but Australian scholars (via Australian Geographic) suggest that the Polynesians had been taking advantage of favorable wind patterns at work in the Pacific for hundreds of years and that when those patterns changed, they no longer had the wind at their back.

Pre-American Hawaii had a strict social structure

Prior to contact with Western civilization, Hawaiian society was incredibly stratified. Everyone in Hawaiian society had a defined role to play based on the circumstances of their birth. At the top, according to HawaiiHistory.org, was the mo'i, or king, who belonged to the ali'i, the chiefly class. The king had a number of privileges that went with his rank. For example, he collected taxes and headed up religious rites and festivals. He also led armies into battle.

Other members of the ali'i, who were said to have descended from the gods, were the children of people whom the mo'i considered superior. Some earned their way into the class by being exceptionally strong or skilled. Others married into it. Regardless, the mo'i had the final say.

Next in the hierarchy were the kahuna, a rank made up of priests and craftsmen whose skills were much sought after. Think "canoe builders" and "medicine men." The other 99 percent were called the maka'ainana. These were the common people who farmed, fished, payed taxes to the mo'i, and served in his army. They were allowed to keep only a third of their goods and pay. The rest went to the ali'i. At the very bottom of the ladder were the kauwa, or "outcasts." Sadly, the kauwa were often prisoners of war. After their capture, they were either enslaved, given the most thankless and difficult of the farm labor, or used in human sacrifice.

To kapu (or not kapu)

For hundreds of years, ancient Hawaiians lived by a very strict code of religious laws called kapu. Kapu governed nearly all aspects of daily behavior, and it was based on the strict stratification of Hawaiian society. The rules, laws, and mores of kapu depended on men and women remaining within their birth-based station in life, and these guidelines were supposedly handed down by the gods (akua) and the spirits of the ancestors (aumakua). Kapu dictated, among other things, what the specific genders could eat, what body parts of a chief a common person could come in contact with, and what color of feathers certain people could wear. Those who violated kapu were often sentenced to death.

The all-encompassing power of kapu began to dwindle as more and more Westerners arrived on the island, bringing with them their own sets of values and a culture based less on social stratification and more on pursuit of pleasure and financial gain. Islanders noticed, for instance, that British explorers lived in hourly violation of kapu and lived to tell the tale. According to The Journal of Polynesian Society, Liholiho (also known as Kamehameha II), son to one of Hawaii's most powerful and beloved kings, King Kamehameha the Great, effectively blew up the system in 1819 by eating in public with a woman, a taboo under kapu.

Things didn't end so well for Captain Cook

Like the Polynesians before him, Captain James Cook is said to have discovered the Hawaiian islands by accident. In 1778, his crew came to Waimea Bay on the island of Kauai at the time of a makahiki, a period of peace and prosperity, and they were treated well by the natives. It didn't hurt that Cook and his men, having come from Tahiti, were somewhat well-versed in island hospitality. The British sailors greeted the Hawaiians with gifts, and the island women returned the favor with, according to the Coffee Times, three days' worth of sexual favors.

A second encounter ten months later on the Big Island went swimmingly, too, probably because Cook again arrived during makahiki. The third time, though, was most definitely not the charm. Cook tried to set sail for the north in early February, but had to return to shore shortly thereafter because of bad weather. Makahiki was over by then, and tensions arose when a Hawaiian man was seen with a pair of pilfered iron tongs. The British pursued, firing muskets, and the Hawaiians threw stones. The conflict escalated a few days later when a British ship went missing. At some point, during a conference on the beach, a shot was fired from one of Cook's vessels, striking an island chief. Confusion ensued, and the Brits were mobbed by the chief's angry subjects. Cook was killed in the fray.

Pre-American Hawaii was a hub for sandalwood and fur trading

Sandalwood and fur might, at first glance, seem to have very little in common, but the two commodities were inextricably linked in the history of pre-American Hawaii. Captain James Cook was the first white man to step ashore in Hawaii — he did so in 1778 — and Americans and continental Europeans soon followed. And so did the fur trade.

As Harold Whitman Bradley writes in The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, the islands' ready supply of salt made them a natural stop on the fur traders' journey from New England and the Pacific Northwest to China. The salt was useful in curing animal hides. Plus, China wanted sandalwood used for making furniture and incense. Fur traders got rich, trading the wood for oriental silk and porcelain, and by selling the porcelain and silk in the states at bonkers profits.

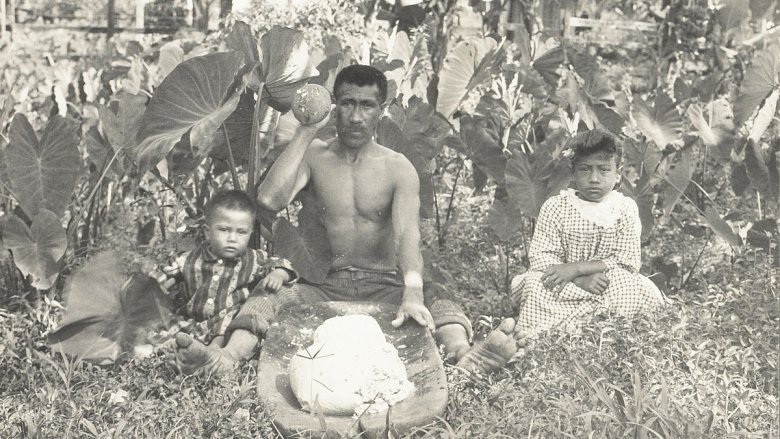

It seemed for a while to be a win-win-win, but it wasn't long before, according to Keola Magazine, Hawaiians began suffering the consequences of the sandalwood boom. Native sandalwood cutters were exploited as cheap labor and began dying from harsh conditions and overwork. The sandalwood forests dwindled, meaning workers had to go further and further up the mountains to find trees to cut. At one point, Hawaiian parents started pulling sandalwood trees from the ground, to save their children from the sad fate of being a sandalwood cutter, and Americans eventually started raising cattle where sandalwood once grew.

The region was a whaler's paradise

Prior to becoming the 50th state, Hawaii was a land of untapped, or at least unexploited, riches. And that includes creatures swimming around in the sea. According to Keola Magazine, whales were one of the islands' greatest sources of pride and identity. Unfortunately, whalers from New England began moving to the islands in great numbers in the early 1800s in order to take advantage of the endless appetite for lamp and heating oil. They were also hoping to capitalize on the demand for whale bone corsets, umbrellas, and buggy whips. Whalers in search of a fortune flocked to the islands, to Oahu and Lahaina in particular, and in doing so, they changed Hawaiian culture, often for ill.

Whalers wanted fun, and they wanted women, so gambling and prostitution flourished. They also craved foods that were known to them, and that meant that native Hawaiians had to switch their crops and fishing habits. Shortly after the whalers arrived, Christian missionaries began docking in Hawaiian ports, and men of the cloth did their best to show the whalers the error of their ways. The missionaries got shot at for their trouble. A fort was built to try to protect local populations from the whalers' violent actions. Then the fort was demolished, and workers used bricks from its downed walls to build a jail — also for sinning whalers.

Finally, in 1859, oil was discovered in Pennsylvania, and whaling became a thing of the past.

On a mission from God

At the same time whalers were discovering Hawaii — right around 1820 — missionaries from America began arriving on the islands to convert the natives to Christianity. It didn't hurt the missionaries' cause that kapu, the ancient Hawaiian system of religious practices and social norms, had been effectively abolished the year before. Men of the cloth and women of God arrived on the scene and filled a vacuum, convincing many native Hawaiians that Jesus Christ was more powerful than all of their gods combined.

According to "Civilizers or Conquerors: The First Missionaries in Hawaii," the Christians (read "white Protestants") who sailed to Hawaii at the beginning of the 19th century were incredibly effective in their efforts to sway native islanders to their cause. By promising to protect Hawaiians from an unruly and often violent invasion of whalers, they assembled congregations in no time, and soon even King Kamehameha the Great was worshiping in one of their churches.

The legacy of the Christian missionaries in Hawaii is a checkered one. Their arrival almost certainly helped strip power from native chiefs and kings and spurred the effort to claim Hawaii for the United States, but they also succeeded in making Hawaiian a written language and, according to Marinalife, they opened up what's now the oldest functioning American high school west of the Rockies.

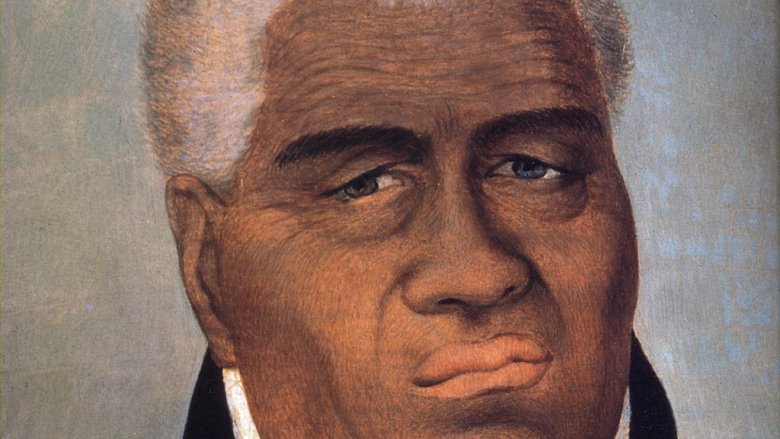

A great king claims his throne

In the centuries prior to Western influence, Hawaii's main islands were ruled by countless chiefs and kings, among whom conflict raged almost constantly. One of those kings, King Kamehameha the Great, stands out, both for his intelligence and his single-minded determination to unify the archipelago under one government.

And the government, of course, was his.

According to the National Park Service, Kamehameha seemed destined for greatness. Born Pai'ea in the 1750s to a Kohala chieftan and the daughter of a Kona chief, the boy who would eventually be king was sent away from home to live in relative seclusion for the first five years of his life, presumably to protect him from harm. He then trained alongside his father and, later, his uncle. As a young man, he was known for his cunning and his war-like demeanor. He was also known for his long-standing feud with his cousin, Kiawala'o, the presumed heir to the throne of the Big Island.

After the death of Kiawala'o's father, Kalani'opu'u, Kamehameha and Kiawala'o waged an incredibly violent and protracted civil war for the right to rule the island. Kamehameha, ruthless and armed with Western guns and cannons, eventually triumphed in 1790. He brought all the islands under his rule in short order, and even though the battle for power was bloody, his reign was, for the most part, peaceful and prosperous.

Pre-American Hawaii was a very sweet place

Hawaii's economy saw a number of fluctuations after Captain James Cook and his crew discovered the islands in the late 1700s. First, there was the fur trade and the sandalwood boom. Then came whaling. When the whaling industry went under, Christian missionaries working to save souls on the islands quickly changed course and began buying up land for another cash crop: sugar cane. Hawaii's climate was perfect for growing the sweet stuff, and the God-fearing businessmen went planting so much sugar cane they had trouble finding enough men to cut it.

According to the Grove Farm Sugar Plantation Museum, one of Hawaii's oldest sugar cane plantations, Hawaiian sugar cane farmers benefited not only from Hawaii's wet climate but from the American Civil War, which ravaged Southern crops and made a market for island ones. Eventually, Hawaii would support what many called "the Big Five" sugar cane growers — Castle & Cooke, Alexander & Baldwin, C. Brewer & Company, American Factors, and Theo H. Davis & Co. — and the heads of these firms didn't stop at sugar production. They became savvy politicians, managing in a relatively short amount of time to take power away from native Hawaiians and put it in the hands of the islands' white minority population.

As Time puts it, the Big Five, "by virtue of interlocking directorates and interlocking marriages, controlled wholesale and retail business, agriculture, banks, land, shipping, society — everything."

The first and only female queen of Hawaii

While white Western men — Christian missionaries-turned-millionaire sugar cane producers — worked privately to deprive native Hawaiians of power, Queen Liliʻuokalani was working just as hard to hold on to her people's traditions. According to Smithsonian.com, Liliʻuokalani was born Lydia Kamakaeha in 1838 to a high-class family, and when King Kamehameha V died without naming a successor, the Hawaiian legislature nominated Lydia's brother, David Kalakaua to the post. Then David died in 1891, and Lydia, now Liliʻuokalani, assumed the throne, making her the first woman in recorded Hawaiian history to do so.

Her time at the top was severely limited, however, by the backdoor dealings of Hawaii's most powerful men, white settlers who'd made a fortune producing sugar cane and pineapples. Sanford Dole had succeeded in nearly monopolizing the growing of pineapples on the island, and he was determined to push Liliʻuokalani to the sidelines. He eventually succeeded in having her arrested for treason and in convincing the U.S. to annex the islands. Liliʻuokalani, a gifted songwriter and a heroine to her people — and the wife of an American — ceded her throne in 1893.

Hanging ten

Before anyone had heard of moondoggies and beach blanket bingo, Hawaiians were sliding on the waves on makeshift surf boards made of balsa wood. They didn't call what they were doing "surfing," though. They called it "wave sliding," and Hawaiian Olympic swimmer and champion waveslider Duke Kahanamoku (pictured above), who grew up in the years before Hawaii became a state, was the unofficial ambassador of the sport.

According to Surfer Today, Kahanamoku is considered the father of modern surfing. He was born in 1890 and made a name for himself first as a swimmer, taking the gold and silver medals in the Stockholm Olympic Games in 1912. Two years later, he was the uncontested hero of the Freshwater Beach surfing exhibition in Sydney, Australia. Handsome, charismatic, and multi-talented — out of water, he was a brilliant ukulele player and an amateur historian — he inspired a whole new generation to hang ten.