Weird Things You Didn't Know About Helen Of Troy

As legendary beauties go, few are as legendary or as beautiful as the mythic Helen of Troy, whose physical charms were such she embroiled two great nations and multiple gods into fierce war for a literal decade. Helen became the cause of the Trojan War when used as a bargaining chip by three vain goddesses who bribed the mortal prince Paris with Helen's love if he would choose correctly in a divine beauty pageant. From the absurd image of three goddesses showing off to a prince who thinks he's a shepherd came the most famous war in all of Greek myth, which left a city destroyed and a people lost and wandering, and at the heart of it all was Helen of Troy.

But who is this Helen? What is it about That Girl she's worth losing a city over? If all you know about the woman torn between two men and two continents is a war was fought over her, gird your mental loins, because there's a lot of weird stuff you don't know about Helen of Troy.

Helen of Troy wasn't from Troy

If you didn't know anything about Helen of Troy–if you didn't know how she was the most beautiful woman in the world, if you didn't know about her being basically the MacGuffin at the heart of the Trojan War–you could probably assume two things from her name: she was called Helen, and she was from Troy. Well, only one of those things is true. It would actually be more accurate to call her Helen of Sparta (which, to be fair, some people do), because she was born, raised, and married there. As the Encyclopedia Britannica explains, she didn't go to Troy until the Trojan prince Paris took her there (willingly or unwillingly, a subject on which mythology is uncharacteristically ambiguous) as his prize for picking Aphrodite as the winner in a beauty contest.

In fact, her presumed father was the king of Sparta, Tyndareus, and her first (and technically fourth) husband was also the king of Sparta. The poet Stesichorus says Tyndareus once forgot to make a sacrifice to Aphrodite, and as a result, she cursed his daughters so they would be doomed to leave their husbands and marry multiple times, a fate that definitely applied to his step-daughter Helen as well as his biological daughters Timandra and Clytemnestra. (The latter not only left her husband but in fact stabbed him to death in the bathtub.)

Helen of Troy was born from an egg

Tyndareus was only Helen's "presumed" father because, as was true of so many notable people in Greek myth, her father was actually Zeus. Although Tyndareus raised Helen as his own, he probably suspected something was up because Helen (and her sister Clytemnestra and two of her brothers) hatched from a giant egg, which is pretty rare for human births.

In the most common version of the Helen story, her mother was Leda. If you've seen any art showing a woman getting very cozy with a swan, that's Leda. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, Leda was a princess of Aetolia who married Tyndareus and then one day a swan flew into her arms to escape a pursuing eagle. This swan turned out to be Zeus in disguise, and he used all his avian charms to seduce Leda and before she knew it, she was laying two enormous eggs full of four babies from two different fathers: the semi-divine Helen and Pollux, children of Zeus, and the fully human children of Tyndareus, Clytemnestra and Castor (the combination of children and eggs varies). Even ignoring the egg part, you may wonder how a woman can have quadruplets from two different fathers, but the ancient Greeks didn't know about gametes and such and believed in a process known as telegony, which meant a child could kind of have two fathers.

Helen of Troy might have been born from a slightly different egg

While the story of Leda, the swan, and the giant human eggs is probably the best known version of Helen's birth, it's not the only one, nor is it likely the earliest one. The good news, for simplicity's sake, is pretty much every version features people turning into birds and babies coming out of giant eggs.

The mostly lost epic poem Cypria records Helen's mother was actually Nemesis, the goddess of righteous retribution. Zeus wanted to get with her, but she was like "nah" and turned into a goose and flew away, but Zeus was like "yes, actually" and also turned into a goose and chased her and, well, you know. Zeus gets what he wants. Nemesis laid an egg that was then transferred to Leda, who hatched it and raised the divine baby she found inside, like the highest-stakes Kinder Surprise of all time.

Because of the similarity of Helen's Greek name (Helene) to the word for "moon" (Selene), Helen was often associated with the moon. In fact, one follower of Pythagoras (yes, the triangle guy) suggested Helen was in fact born on a moon colony but her egg dropped to Earth where she was hatched. While this would explain her unearthly beauty, the argument against this is, of course, moon people are fifteen times larger than Earth people.

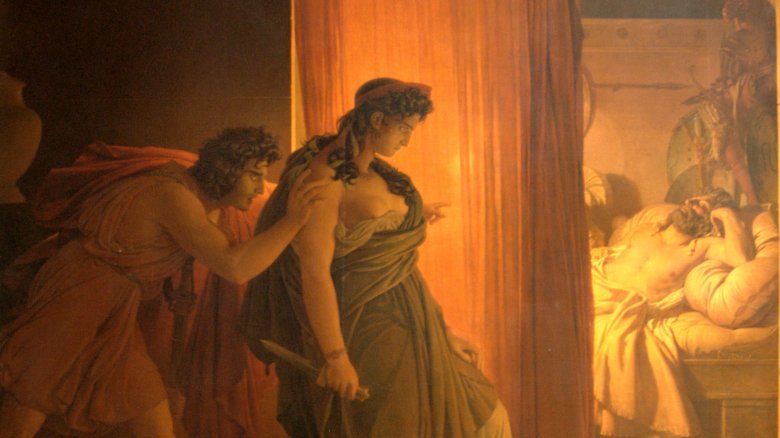

Helen of Troy wasn't the only famous member of her family

Helen's egg siblings were famous in their own right (her non-egg step-sisters are pretty negligible, however). As the Encyclopedia Britannica says, her sister Clytemnestra married Agamemnon, the richest king in Greece and the commander of the Greek forces at Troy (and also the brother of Helen's husband, Menelaus). Their relationship was not super great, though: Clytemnestra got so mad when Agamemnon sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia (long story) that while he was away at war for 10 years, she hooked up with a guy named Aegisthus and plotted Agamemnon's murder when he returned home (the aforementioned bathtub stabbing). But you know how it goes: Clytemnestra was subsequently revenge-murdered by her children Orestes and Electra and then the kids were pursued by the demonic Furies until Apollo and Athena instituted an all-new concept of non-vengeance-based justice. It was a whole thing.

Helen's brothers Castor and Pollux, known as the Dioscuri ("sons of Zeus"), were twins with different dads who were really good at sports, sailing, and horses. They took part in a lot of Greek myth's most famous adventures, including the search for the Golden Fleece and the Calydonian Boar hunt. When the mortal Castor was murdered, Pollux elected to share his immortality with his brother, so they took turns being dead. Probably the more famous fate of these twins to a modern audience, however, is they were placed in the sky as the constellation Gemini.

Helen of Troy was kidnapped by Theseus as a dare

While the Athenian hero Theseus is best known for traversing the Labyrinth and slaying the Minotaur, the dude had a long life filled with adventures. Some of the wildest of these come as a result of his friendship with Perithous, the youthful King of the Lapiths, which could best be described as an escalating series of dares.

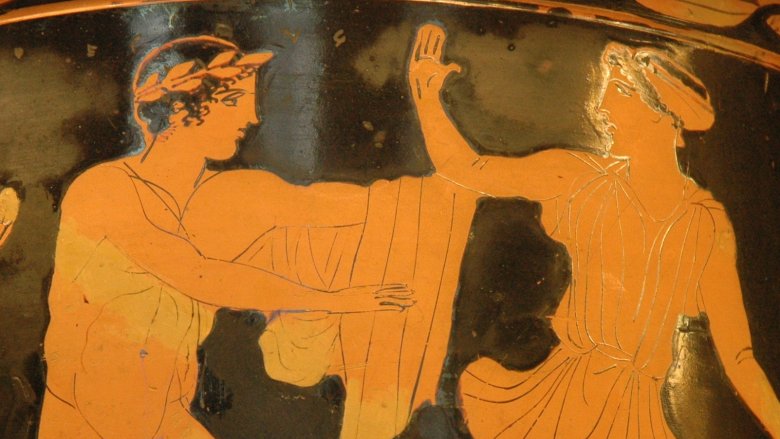

According to the mythographer Pseudo-Apollodorus, after killing a bunch of centaurs that got way too drunk at a wedding, Theseus and Pirithous decided it would be cool if they both married daughters of Zeus. Theseus determined to marry Helen, an actual child at the time, and Pirithous swore to marry Persephone, the literal queen of Hell. Both of these goals involved kidnappings, and both were monstrously bad ideas.

Theseus took the child Helen from Sparta and left her in the care of his mother while he and Pirithous went down to the Underworld for Persephone. Obviously, the two idiot boy kings got trapped in the Underworld for a while in a magical snake chair (Theseus was eventually rescued–minus some thigh meat–by Heracles; Pirithous wasn't so lucky); meanwhile, Castor and Pollux led an invading force against Athens, not only reclaiming their sister Helen, but also taking Theseus' mother back to Sparta with them as a slave for good measure.

The kings of Greece had to promise not to kill Helen of Troy's husband

When Helen was actually old enough to get married, Tyndareus found himself with a pretty serious problem: how do you choose a husband for the most beautiful woman in the world? According to Pseudo-Apollodorus, the potential suitors were pretty notable names if you're familiar with the story of the Trojan War: Diomedes, both Ajaxes, Philoctetes, Patroclus, of course Menelaus, and many more. Tyndareus was rightly worried showing preference to one of these kings over the others could lead to literal violence with armies and all. The good news for Tyndareus, though, was one of the suitors present was Odysseus, the smartest guy in Greece, who knew he didn't stand a chance in this contest and was actually more interested in marrying Penelope, who was more his intellectual equal (you may have heard of her).

Odysseus suggested a compromise that came to be known as the Oath of Tyndareus: once Helen's dad made his pick, every king present would swear a blood oath to throw his military might into avenging the chosen one if anything should happen to him. This agreement made, Tyndareus chose Menelaus as his son-in-law and heir and helped Odysseus win the hand of Penelope.

It was this oath that led to one thousand ships being launched to get Helen back for Menelaus once Paris made off with her.

Helen of Troy might have actually been Helen of Egypt

So even if Helen of Troy wasn't from Troy, she definitely at least went there, right? Like, that was the whole point of a 10-year war in which many of the leading lights of Greece and Troy became a feast for crows. Well, uh, maybe not. According to a number of authors, including perhaps most notably the tragedian Euripides, the Helen who went to Troy was actually a hologram made of clouds, while the real Helen was taken to Egypt by Hermes, where she lived out the entirety of the war.

In Euripides' play Helen, the titular Spartan queen receives word her husband Menelaus has drowned while returning from Troy, leaving her open to the advances of the king of Egypt. At that point, however, a stranger washes up on shore who, as luck would have it, turns out to be Menelaus. The two reunite and explain to each other the various hologram-related shenanigans that got them to this point before coming up with a plan to trick the king of Egypt and escape back to Sparta, with Helen's beefy god-brothers Castor and Pollux showing up ex machina to stop the Egyptian king from murdering his sister who helped them.

This version of events sounds buck wild, but the historian Herodotus claimed he interviewed Egyptian priests who could confirm Helen was definitely there, so who can say, really?

Whose side was Helen of Troy on?

One thing the various authors of myths couldn't seem to agree on is where Helen's loyalties lay. If she was, in fact, kidnapped against her will by Paris, it seems clear she would be hoping the invading Greeks would win the war, so she could return to Menelaus and their daughter, Hermione. If, instead, she was in love (whether naturally or through the influence of Aphrodite) with Paris, it seems reasonable she would want to stay in high-walled Ilium with her new beau. Each version has its own supporters.

In the Greek epic the Odyssey, Homer tells how Helen tried to expose the trick of the Trojan Horse by circling it and doing impersonations of each of the Greek kings' wives in order to fool them into replying and exposing themselves. It almost worked, too, but the clever Odysseus figured out what she was doing and clamped shut the mouths that needed clamping.

The Roman author Virgil, however, says Helen remained true to the Greeks. In book six of his epic the Aeneid, the ghost of Deiphobus–a prince of Troy and Helen's third husband after his brother Paris was killed–tells how Helen went out into the city pretending to perform a religious rite just so she could signal to the Greeks inside the Horse. For whatever reason, neither author wanted to claim Helen for their side.

Helen of Troy might have been lynched by cosplayers

According to various sources (including the comedian Aristophanes), Menelaus raised a sword to his unfaithful wife when storming the conquered Troy, only to be moved to mercy when she flashed him her, you know, beautiful bosom. At any rate, in arguably the most mainstream version of the story, Helen and Menelaus reunite and reconcile, returning to Sparta (where Odysseus' son Telemachus encounters them while looking for news of his father in the Odyssey). They live together and die together and are buried together, happily.

The geographer Pausanias, however, records a completely different version of events told by the inhabitants of the island of Rhodes. According to him, the Rhodians say after Menelaus' death, Helen was driven out of Sparta by Menelaus' sons (who were not also Helen's sons) and made her way to the home of a friend on Rhodes. What Helen didn't know is this "friend" blamed her for the death of her husband, who died on the first day of the Trojan War. The Rhodian queen waited until Helen was bathing and then sent out a bunch of her handmaidens dressed up as the Greek revenge-demons the Furies. These maids, apparently wearing fake bat wings, dog masks, and snake wigs, grabbed Helen from the water and strung her up from a tree, where she really died, not a hologram.

Helen of Troy was worshiped as a goddess

Due to a combination of the facts Helen was a demigod daughter of Zeus married to a legendary king, and she probably originated as a goddess who got "demoted" to demigod status as her story got refined over the years, Helen of Troy was worshiped in various spots around Greece and in various ways.

One of the major shrines to Helen was shared with her husband, Menelaus. According to the University of Warwick, the Menelaion was located just east of Sparta in an area known as Therapne. Though it came to be regarded as the burial place for the legendary couple, some suggest the shrine was originally dedicated to Helen alone, where she was worshiped as a fertility goddess, only for the Menelaus-related elements to be added later. Elsewhere in the region of Sparta, Helen's cult was associated with women's gymnastics and choral dancing.

Pausanias tells how the Rhodians worshiped Helen as a fertility goddess known as Helena Dendritis (Helen of the Trees), with her shrine naturally being the tree where she was hanged. He further says in a temple on the acropolis of Sparta hang bits of eggshell, tied with ribbon, which people believed to be part of the egg from which Helen and her egg-siblings were hatched. He says he went to Sparta to see these eggs for himself, so put that one in the "true" column.

How do you paint the most beautiful woman who ever lived?

If you've ever engaged in any type of creative endeavor–be it a sculpture, song, or amusing historiographical listicle–you've probably felt pressure to recreate the perfect image in your head, to do justice to the spirit of the person, place, or theme that inspired you. Imagine, then, the immense pressure to paint a portrait of the most beautiful woman who ever lived. That was the task facing the legendary Greek painter Zeuxis when he was commissioned to envision Helen of Troy in paint to decorate a temple of Hera.

You might have heard of Zeuxis if you know the story about the painting contest where one guy painted grapes so realistic birds tried to eat them, but then he asked his rival to pull the curtain off his painting, only to find out the curtain was the painting and so he lost the contest because the first painting fooled a bird, but the second painting fooled a great painter? Zeuxis was the grape guy.

According to the College Art Association's review of a book about him, Zeuxis' reaction to his assignment was to say perfection isn't found in nature, so he would find no single suitable model for Helen of Troy. Instead, he recruited five different maidens, whose best features he combined into a single figure like some kind of erotic Voltron. The scene of Zeuxis picking his models became a popular artistic motif itself in modern times.

Helen of Troy goes metric

In 1604, English playwright Christopher Marlowe penned a line about Helen of Troy more famous than anything Homer ever conceived of. Doctor Faustus sees a demon assuming the form of the legendary beauty and says, "Was this the face that launched a thousand ships?" The line has its basis in Lucian of Samosata's satirical Dialogues of the Dead, but it's one of those things that's so entrenched in culture few people know its origin apart from it being a thing you say about Helen of Troy.

The line also became the basis of one of the most famous goofs drawn from that common well of comedy, the metric system. As the Back of the Cereal Box blog recounts, the idea of a metric unit of beauty based on Helen of Troy is often attributed to Isaac Asimov, apparently in one of his more whimsical moods, though mathematician W. A. H. Rushton sometimes gets the credit. The idea is if a Helen is the amount of beauty necessary to launch 1,000 ships, then this is a unit that could be broken down in a decimal fashion, and thus a milliHelen would be the amount of beauty necessary to launch one ship. Now you have an empirical measurement by which you can compliment your nerdy loved ones. Use it wisely.