Things In Midway You Won't Believe Were True

If there's one thing that can be said for people today, it's that they're used to seeing big-screen productions that tell the story of real events and people ... but take more than a bit of creative license with the truth. Real events tend to be painted with broad strokes by an artist that doesn't have much regard for the truth, and they're hyped up for the sake of making an impressively unbelievable tale, fit for the silver screen.

But here's the thing with Roland Emmerich's Midway: there's a ton of moments that just sort of have audiences shaking their collective heads, there's a ton of things that just seem too insane to be true. But for the most part, it's the sort of accurate that makes people believe truth really is stranger than fiction.

According to Time, this was Hollywood's chance to do a few things. They wanted to tell the story properly, bring a pivotal but often-overlooked battle to the forefront, and make up for the missteps made by the 1976 film based on the same events. Screenwriters used source material that included interviews and oral histories from eyewitnesses, and it makes for a crazy story that's true — even these parts.

Bruno Gaido's showdown with a Japanese bomber

The majority of characters in Midway are based on real people, including Nick Jonas's Bruno Gaido. Remember that incredibly unlikely, insanely mad scene where the USS Enterprise is raided by Japanese bombers, only to have them all miss ... save one, that's been badly damaged and is about to just crash into the ship? Gaido hops into a nearby dive bomber and starts shooting, only to send the bomber careening away at the last minute, at the same time the plane he's in takes a direct hit.

Surely, Hollywood drama, right? It's absolutely true. According to the Naval History and Heritage Command, Gaido really did take a running leap into a parked plane then opened fire on a Japanese bomber intent on crashing into the Enterprise (pictured), just like the movie depicts. The Japanese bomber did actually clip Gaido's plane, slicing off the tail and sending it skidding across the deck.

There is a tad bit of creative license that was taken with this one — the real story of the aftermath of the incident was that Gaido first extinguished a gasoline fire started when the bomber clipped him, then he disappeared. He had been afraid he was going to get reprimanded for leaving his watch position, but instead, he was found, taken in front of Admiral Halsey, and promoted on the spot — just like the film shows.

Torpedo duds

Even the bravest military is going to fail without reliable weapons and equipment, and that makes it all the more shocking that Midway suggests those on the Pacific front were fighting and using torpedoes that didn't exactly work. The film makes several mentions of torpedoes not being tested or reliable, and even showing one scoring a direct hit only to break apart and sink. Unlikely-sounding? Yes. True? Yes.

According to The National Interest, the Mark 14 Torpedo was about as completely useless as it could be. After Pearl Harbor, Admiral Chester Nimitz (portrayed in Midway by eerie lookalike Woody Harrelson) declared open season on all Japanese shipping. The USS Seawolf had a freighter in her sights just a week after Pearl Harbor; seven of her torpedoes missed, one hit, and that one? Didn't explode. When the Tinosa spotted a 19,250-ton tanker called Tonan Maru No. 3, the first four torpedoes hit and did nothing. The next two hit and exploded, crippling the tanker. The next? Nothing. The one after that? Nothing. It took another six torpedoes before one hit and exploded, and by then, the Tonan Maru was calling for help. Two more torpedoes failed to fire, and the American sub left without sinking her prey.

And the military knew it, sending the torpedoes into combat even though they had around a 50 percent failure rate. Just a few months after Pearl Harbor, that had increased to around 80 percent.

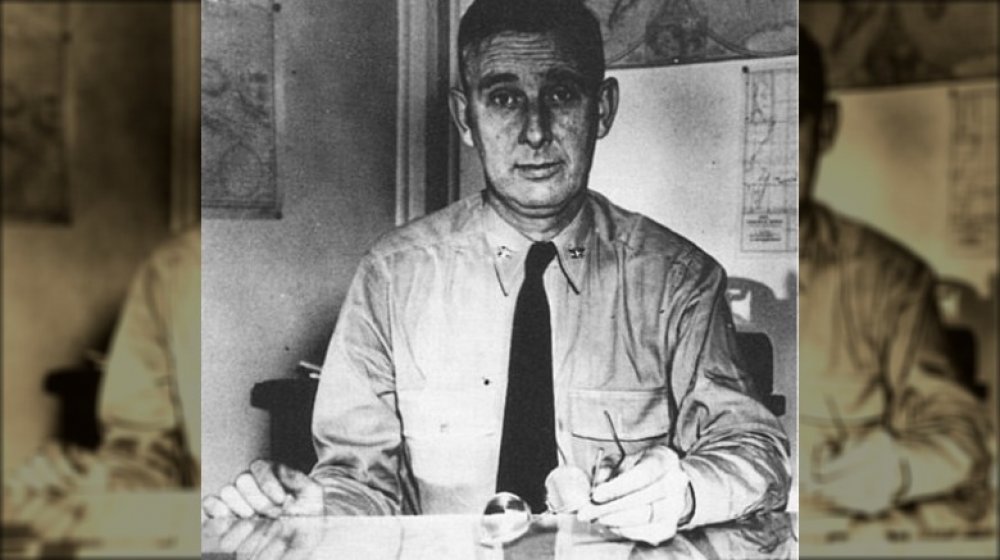

Rochefort and his fuzzy slippers helped win Midway

Midway's Joseph Rochefort (Brennan Brown) is portrayed as a quiet, soft-spoken, brilliant intelligence analyst who's just a little eccentric. That's a huge change from the way he was portrayed in the 1976 film about Midway, where Hal Holbrook turned him into a careless, loud, cigar-puffing joker. Even though the real Rochefort (pictured) consulted on the earlier film, it was the latter one that got him right — down to the slippers and smoking jacket. According to Joe Rochefort's War: The Odyssey of the Codebreaker Who Outwitted Yamamoto at Midway, there was a very practical reason for the smoking jacket and the slippers. The office they were working out of was cold and damp, and everyone wanted to stay warm.

He really was a brilliant analyst, and he was the one who realized Japanese forces had turned their sights to Midway. According to History, he did have the tendency to bypass proper channels to get information into the hands of the person he knew he could count on: Edwin Layton. The real Layton and Rochefort were long-time friends, too, even having spent three years studying language and culture in Japan together.

And, just like in the film, Washington, D.C. doubted Rochefort's prediction Japan was planning on attacking Midway. He did arrange to have a sub send out a false message Midway was running out of water due to evaporator malfunction and sure enough, when Japan relayed the message "AF" was low on water, they had their confirmation.

Playing chicken with the ocean at Midway

Midway is, without a doubt, a visually stunning movie that puts audiences right in the cockpit of World War II dive-bombers. And it seems insane, that pilots would literally dive through a rain of fire to try to hit and sink massive ships. But they did.

The Douglas SBD Dauntless dive-bomber (pictured in the film) was the plane known as "Slow But Deadly," says The National Interest. Remember, they were flying at a time when aircraft were still pretty bare-bones, and in the mid-1930s, both the Navy and the Marines were beginning to appreciate the death-defying practice of dive-bombing as the best way to accurately aim, and they were building aircraft suited to it. The Dauntless had things like split flaps and dive brakes, and allowed pilots to dive at an 80-degree angle at speeds nearing 300 mph. Dives usually started at around 12,000 feet, and the effects could be devastating.

They turned the tide at Midway, when — taking advantage of a sky momentarily clear of Japanese fights — Commander Clarence McClusky (Luke Evans) led just a handful of dive-bombers against the Japanese fleet, mortally damaging three of the four carriers in around five minutes.

The daring determination of the Doolittle Raid during Midway

The Doolittle Raid is treated as something of an aside in Midway, a daring mission happening alongside the main action. We see Jimmy Doolittle (Aaron Eckhart) and his men — knowing they're taking off from a carrier and heading into enemy territory with no guarantees they were carrying enough fuel to get them to safety — heading out to launch some serious retaliation on Tokyo. Eckhart's Doolittle makes it into Japanese-held China and meets up with allies happy to see the Americans who struck a blow to their oppressors.

Again, absolutely true. National Geographic says the mission was so secret that FDR wasn't even informed about it at first, and the entirety of the Army Air Corps' 17th Bombardment Group volunteered to fly alongside Doolittle (pictured, fifth from left). Included in their training was repeated practice of a phrase in Chinese, one that translated to "I am an American."

The plan was to take off around 300 miles from Japan's shores, but — as in the film — they were forced to take off much, much earlier. The fleet was spotted when they were 700 miles out, and according to Naval History and Heritage Command, the early launch may have saved the mission. Japanese commanders knew the short range of American fighters and weren't expecting a long-range launch — and weren't ready for it. The 16 B-25s hit targets in five Japanese cities, and 15 went on to crash in China, while one made it to Vladivostok.

Japan's retaliation on the Chinese people

The Doolittle Raid was organized as retaliation for Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, and in Midway, audiences get just a small glimpse of the consequences. Chinese allies are escorting Doolittle out of the remote, rural countryside he parachuted into, and they're strafed by Japanese planes. He asks what the target it, and they simply respond that they are.

That was just a glimpse of the atrocities that followed. In retribution for the attack on Tokyo and the aid villagers and missionaries gave to the pilots, Japan killed somewhere around 250,000 Chinese. According to the Smithsonian, most Japanese allies didn't even know about it, and the extent of the payback wasn't fully known until documents were recently rediscovered at DePaul University.

Doolittle hit Tokyo on April 18, 1942, and by June, the killing started. One American priest would write, "They shot any man, woman, child, cow, hog, or just about anything that moved ... None of the humans shot were buried either, but were left to lay on the ground to rot..." There were 28 towns in the region that the Americans landed in, and only three towns survived. As in the film, small thank-you gifts airmen gave those who helped them were used to target families and individuals for torture, and even as Japanese troops withdrew, their Unit 731 — specializing in bacteriological warfare — spread typhoid, cholera, plague, and anthrax in their wake.

An admiral sidelined at Midway by a rash

It's an odd little detail, at first: Admiral Halsey (Dennis Quaid) complains of a rash. It quickly gets worse, and Halsey is ordered to step down and head to the hospital. Even those with a passing knowledge of World War II's Pacific Theater have heard of Rear Admiral William F. "Bull" Halsey, so... what gives? Was he really sidelined by a rash?

Yes. According to the US Naval Institute, it was just one of a handful of incidents where illness impacted command. (To give an idea of how important that moment, Admiral Halsey, and Midway all were in military history, others on the list include Alexander the Great and Napoleon.) That rash was a severe case of psoriasis, and it was so bad it was interfering with his ability to make decisions.

One small difference — in the film, it's said to be shingles. What's the difference between the two? According to Healthline, shingles can spread from person-to-person, while psoriasis isn't contagious, isn't curable, and will regularly flare up in people who have it.

Richard Best's unlikely dive-bombing success at Midway

Ed Skrein's hot-shot pilot Dick Best seems like the fictional hero written in to make a movie more interesting and give it a central character, but he was very real and every bit as good as he's shown to be onscreen.

Screenwriter Wes Tooke first read about him in a book by historian Barrett Tillman, who wrote that if the Olympics ever decided to include dive-bombing, he'd take the gold (via Time). When he died in 2001 at the age of 91, press reports (via Arlington Cemetery) lauded him — and his squadron — for turning the tide of the battle. Skrein's Best scores several critical hits on several different carriers, and it seems like the unlikely skills of a fictional (or at least fictionalized) character. But according to the Smithsonian, it's true — Best and Dusty Kleiss were the only pilots to score multiple hits on different carriers during the battle for Midway.

Best's career ended just as it's shown onscreen. After breathing caustic soda from a faulty oxygen canister, his tuberculosis flared up. He was awarded the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and was inducted into the Naval Aviation Hall of Fame.

Repairing the USS Yorktown in time for Midway

When audiences see the USS Yorktown after the Battle of Coral Sea, she's in dismal state. She's in dry dock, gaping holes in her deck, with crews that are dwarfed by the sheer size of the damage they're trying to fix. But in the film, she's back on the water and sailing in to save the day just hours afterwards. Unlikely? Yes. But also true.

According to the US Navy, the Yorktown (pictured, in Pearl Harbor's dry dock) returned to Pearl Harbor with an open hull, leaking oil, and sporting enough damage it was estimated that — best case scenario — it would be 90 days before she was operational again. A 551-pound bomb had sliced through the deck and detonated 50 feet into the ship, destroying six compartments, lighting systems on three decks, radar, refrigeration, and rupturing fuel-oil compartments. Her hull was cracked, elevators non-functional, and she had left 10 miles of oil and fuel in her wake.

When she returned to Pearl Harbor, plans for Midway were already underway. Admiral Nimitz gave them three days to get the Yorktown back in the water ... and they did it. Around 1,400 workers labored for 72 hours straight on repairs that were so intensive the island was subjected to a series of blackouts to funnel electricity to the repair docks and — as requested — Yorktown left for Midway where she was torpedoed, capsized, and sunk after launching the aircraft that sank one of Japan's carriers (via ThoughtCo.)

Filming Midway under fire

It's played as a bit of an incredulous moment: John Ford is on Midway, ordering his camera crew to film bits and pieces around the island. Then, Japanese planes strafe the island, and he orders them to keep filming — even though he's been injured.

All true.

According to Naval History and Heritage Command, Ford (pictured) was up in the air with a scout mission when he first spotted Japanese aircraft. They returned to the island with no conflict, and the next morning, he was out on the island's power station, watching, when the attack came. Ford was filming through the entire thing, and did, indeed, get a shoulder full of shrapnel mid-battle, says the US Naval Institute. His footage was released as The Battle of Midway in 1942, and he not only got an Academy Award for it, but received a Purple Heart for his wounds. He was particularly impressed with the Marines he was surrounded by during the battle. Averaging between the ages of 18 and 22, he had this to say about them: "They were the calmest people I have ever seen... I figured then, 'Well, if these kids are American kids, I mean this war is practically won.'"

Japan's deadly mistake and delay at Midway

In Midway, American planes have a crucial advantage: time, chaos, and confusion stemming from an armaments change-over by the Japanese military. And that happened.

According to the Smithsonian, the Japanese air fleet was originally equipped with torpedoes, geared for fighting American carriers. Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo gave the order to have everything re-equipped for an attack on Midway, and that meant swapping torpedoes for bombs. The switch was in mid-completion when they got word American ships had been spotted by scouts, and suddenly that meant they needed to swap back to torpedoes again.

What followed was more than chaos: Japanese aircraft were slow to get into the air, and ordnance was left scattered across the decks of the carriers (like the Mikuma, pictured, photographed from the deck of the Enterprise just before sinking). All that ordnance was highly explosive, and added fuel to the fire American dive-bombers started dropping.

Bruno Gaido's terrifying death after Midway

Audiences know going into a war movie that characters we get to know and love are going to die in terrible ways, that's just a fact of war. In Midway, we see gunner Bruno Gaido and pilot Frank O'Flaherty ditching their plane in the open water, making it into a lifeboat and eventually spotting a ship. It turns out to be Japanese, and they're pulled aboard. Refusing to give any information, Gaido is tied to an anchor and shoved overboard. Their captors turn to O'Flaherty, and his fate is clear.

Gaido and O'Flaherty did ditch their plane, and were pulled aboard the IJN Makigumo, says Naval History and Heritage Command. It's not clear what happened when they were on board, and while Japan long claimed to have gotten information from them, it's believed they were tortured and revealed phony — but completely believable — intel. When they were deemed no longer useful, they were tied to weights and thrown overboard — a fate not discovered until well after the war, and since no officers were ever directly linked to their deaths, there was never any prosecution for war crimes.

Gaido was still considered MIA in 1943, when his Distinguished Flying Cross was given to his father. The elder Gaido told The Milwaukee Journal (via Find a Grave), "I don't give up hope. Bruno is still alive, maybe on a little island. He always had a lot of courage and could fight."