Things Harry Potter Gets Wrong About Mythical Beings

The Harry Potter novels and movies are full of magical creatures, and while there are a few that seem to have sprung fully formed from the mind of J.K. Rowling, most of them are drawn from folklore and mythology throughout the world. In fact, Rowling has even said that whenever she planned to introduce a new subject into Harry's Care of Magical Creatures lesson or Newt Scamander's world-traveling adventures in search of fantastic beasts, she dove into research to make sure she got things right.

For the most part, that research paid off, tying Harry and his world even more closely to the folklore that inspired it. Other times, though ... not so much. In fact, in some instances, Rowling got her creatures so wrong that it actually had real-world implications. From snakes that are just too big to plants that are nowhere near scary enough, here are the things Harry Potter got wrong about its mythical beings.

Fluffy is way easier to beat than his mythical counterpart

One of the first major mythological creatures that Harry, Ron, and Hermione encounter in their adventures is Fluffy, the gigantic, three-headed dog who guards the Sorcerer's Stone. In the end, Fluffy turns out to be pretty lousy at the whole guard dog job because he (they?) immediately falls asleep whenever there's music playing, but to be fair, that's not exactly his fault. He's not the one who decided to put a legendary artifact behind a bunch of whimsical traps that could literally be defeated by a trio of slightly above-average children.

Anyway, while Fluffy isn't the same creature, he's pretty clearly inspired by Cerberus, the gigantic. three-headed dog who guards the entrance to the underworld in Greek mythology. On the whole, Cerberus is about as effective at keeping people out of Hades as Fluffy is at keeping people out of the third-floor corridor. The myths are full of stories of people just bopping down to the afterlife. He isn't, however, susceptible to the same lullaby weakness. Or at least, that's not the tactic his opponent uses in the most prominent example of someone defeating him.

As students of mythology may already know, subduing and capturing Cerberus without using a sword was the last of the famous 12 Labors of Hercules, and it didn't go down with a gentle melody from a harp. Instead, according to Apollodorus of Athens — the possibly-not-real figure who compiled all these myths back in the first century CE — Herc just beat Cerberus with a rock and then put him in a chokehold until the dog passed out, which is especially impressive when you consider that he had at least three necks. The poet Pindar wrote that Cerberus actually had 100 heads, while Euripides wrote that Cerberus actually had three heads and three bodies. Euripides ... buddy ... that's just three dogs.

Harry Potter pays too much attention to unicorn blood

We get a brief glimpse of a truly magical creature in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone when Harry has to serve detention in the Forbidden Forest and catches Voldemort (uh, spoiler warning?) drinking the blood of a slain unicorn. According to Firenze the centaur, killing a unicorn leaves an indelible stain on one's soul, but the trade-off is that drinking its blood will keep you alive, even if you're hovering on the verge of death.

If you know anything about the history of dubious and allegedly magical cures, it won't surprise you to know that people in the past actually did believe that unicorns were real and possessed of mystical healing properties. What might come as a surprise, however, is that this was a common belief as recently as the 1700s, and that it wasn't the blood that people were interested in. It was, of course, the horns.

Powdered unicorn horn was sold by hucksters and con men in the 17th and 18th centuries as a cure-all for stuff like smallpox, one of the deadliest diseases on Earth. Obviously, it didn't work, and smallpox continued to be a problem until it was officially declared eradicated in 1980 thanks to vaccines, which are a handy thing to have around since unicorns don't technically exist. As for the powder, it could've been virtually anything, but the closest it ever came to being authentic was when it was made from the horns of narwhals, which — if you didn't know that narwhals were real and unicorns weren't — would've been pretty darn convincing.

Are goblins actually nice?

Even before Harry gets to Hogwarts in the first book, he encounters goblins — the gold-loving, vaguely sinister beings who run Gringotts Bank. Of course, these guys have since joined the ranks of fantastical creatures who've drawn heavy criticism for bearing a striking similarity to anti-Semitic stereotypes, and folks, there's a heck of a case to be made there. At least Star Trek's Ferengi and Star Wars' Watto didn't literally run banks.

The thing is, they don't exactly match up with the folkloric goblins, either. Nowadays, thanks their appearances in the works of J.R.R. Tolkien and their status as a go-to, low-level monster in Dungeons & Dragons, the word "goblin" is mostly associated with diminutive, inherently evil monsters who are slightly easier to beat up than orcs but a little more challenging than kobolds. Originally, however, the word was more like "fairy" or "pixie," a catch-all term for any small magical being that could be friendly or mischievous depending on the story being told. In fact, rather than the opportunistic bankers we see in Harry Potter, one of the earliest uses of the term refers to a purely benevolent being.

The Gesta Romanorum, a collection of folktales dating to the late 13th century, contains the appropriately titled story of "The Benevolent Goblin." When parched travelers in a particular area announced "I thirst" — quoting Jesus on the Cross, since, like a lot of medieval literature, this one likes to mix Christianity and the supernatural — a friendly goblin would emerge, offering the traveler a drink from a golden chalice. Unfortunately, word got out, and an evil knight showed up and stole the chalice, ruining it for everyone. But hey, considering that goblins wanting their artifacts back winds up being a major plot point by the end of the Harry Potter series, maybe that's the origin story for why goblins and wizards don't get along.

The basilisk is an itty bitty boy

The basilisk is a legendary animal that dates back to ancient Greece, but in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, one shows up as the key figure in what's probably the most well-crafted whodunnit where the answer is "a giant snake that none of us have ever seen before."

Rowling's basilisk is almost exactly like the mythological one, in that both of them are snakes that have the power to turn their victims to stone simply by looking at them. There is one big difference, though, in a very literal sense. The basilisk in Chamber of Secrets is huge, a 60-foot monster whose gigantic venomous fangs can be used in a pinch as a good-sized stabbin' dagger. Not so with the mythical one. Pliny the Elder, the Human Wikipedia of Ancient Rome, described the basilisk as being "not more than twelve fingers in length," presumably because a snake with super powers is already pretty scary without being huge.

It could be even more off-model, though. The term "basilisk" is often conflated with another mythical creature with petrifying eyes and a similar origin: the cockatrice. A crazy creature that even shows up in the Bible, the cockatrice has the body of a dragon with the head and wings of a rooster, and it's about the same size as a large dog. The big snake is more thematically resonant to Harry Potter, but c'mon, we all know it would be rad to see little Daniel Radcliffe trying to fight a big ol' chicken with dinosaur legs.

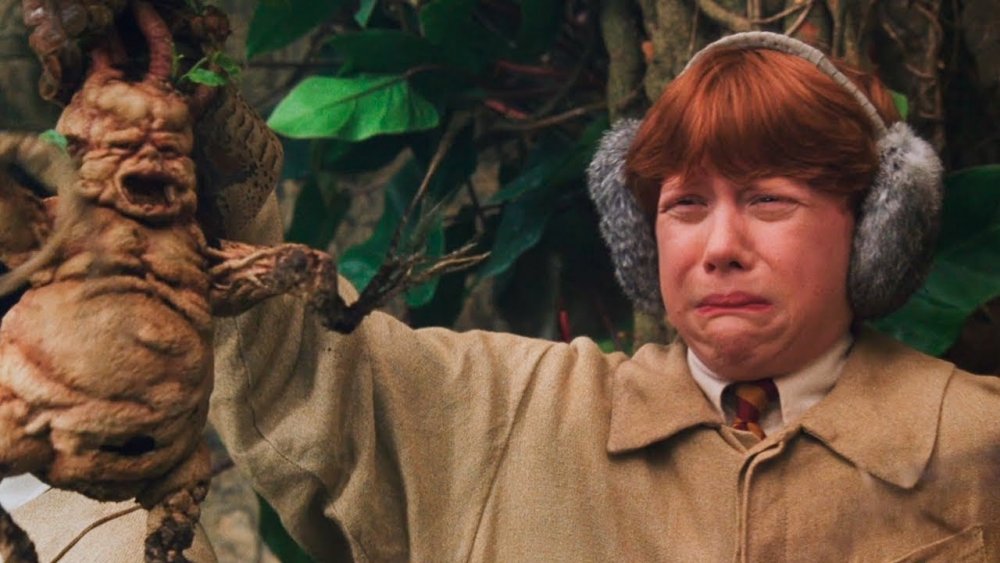

The mythical mandrake is way scarier than the plants in Harry Potter

While it features prominently in Harry's herbology class in Chamber of Secrets, the mandrake plant isn't a made-up magical bit of flora. It's 100 percent real, and while it's not a sentient being with a cry that can strike you dead where you stand, the fact that its roots usually have a vaguely humanoid shape that gives it a weird resemblance to a baby has cemented its prominent place in folklore.

Harry Potter, of course, leans pretty heavily on the more magical side of things, with a particular emphasis on the mandrake's medicinal properties. In the book, it's the main ingredient for curing petrification, but ironically enough, the real-life mandrake, if ingested, can often result in death due to asphyxiation. It has, however, been historically used as an anesthetic to knock people out for surgeries, and it's also the kind of very powerful hallucinogen that might make you wake up talking about seeing a giant snake even if you've never been to Hogwarts.

As for how it differs from folklore, well, Harry Potter gets the part about the deadly cry right, but there's also a tradition about how uprooting a mandrake will condemn the uprooter's immortal soul to Hell. Considering that Professor Sprout's very first assignment with mandrake is uprooting and re-potting it, she might actually beat Snape in the competition for the teacher who presents the most undeniable danger to the students.

So what's up with that ghoul?

If you were going to list the locations in the Harry Potter series by how welcoming and comforting they are, the top entry on your list would likely be the Burrow, the Weasley family's improbably towering home. It's full of whimsical, magical things like the clock that tells you where every member of the very large family is at any given time, the pesky gnomes out in the garden, the friendly ghoul rattling the pipes up in ... wait a second. A ghoul?

Ghouls have their origins in Middle Eastern folklore — the name is from the Arabic word "ghul," which is often translated as "demon" but literally means "to seize" — and were introduced to European audiences with the translation of One Thousand and One Nights into French in 1704. Notably, that version doesn't include friendly pipe-rattling, instead focusing on how ghouls are terrifying creatures who dwell in desolate places and cemeteries, where they feast on corpses, drink blood, and occasionally lure children to their doom.

Molly Weasley is generally depicted as a good mother who only wants the best for her family, but keeping a flesh-eating super-zombie around is probably not a great way to raise children, even if you have four or five spares in case you lose one. Then again, this is the same family that let a mass murderer live in their youngest son's bedroom for a solid decade without knowing it. They're still better than the Dursleys, but maybe not as much as we thought.

The truth about kappa

As you might expect from the author and the setting, we rarely see magical creatures in the Harry Potter books that aren't drawn from European folklore. That might actually be a good thing, though, because Rowling tends to go a little further off-script with those. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban has a perfect example that's worth mentioning, if only because it may or may not have been intentional.

The creature in question is the kappa, which is never actually seen and only spoken of briefly during a Defense Against the Dark Arts class. It's the subject of a homework assignment that Snape angrily criticizes while he's filling in for Remus Lupin, telling students that they got it all wrong, insisting that the kappa is commonly found in Mongolia. Kappa, however, are Japanese — like, distinctly and definitively a part of Japanese folklore — and it turns out that Mongolia and Japan are two different places. We looked at a map, it's wild. The thing is, this might have been Rowling's way of showing readers that Snape wasn't actually qualified for the coveted position of teaching DADA.

If you're curious about what they actually are, kappa are river spirits that resemble humanoid turtles — picture Leonardo and Michelangelo's uglier cousins — that prey on travelers. The trick is that they have bowl-shaped depressions on top of their heads that hold water, and if the water spills, they become powerless, making them one of the few monsters that can be defeated by politeness. If you bow to them, they'll bow back, the water spills, and you can get away without the kappa stealing your shirikodama, a nonexistent organ inside your anus. No, really. Snape never mentions the thing about stealing your butthole, either, but it's definitely in there.

Boggarts aren't so scary

Introduced in Prisoner of Azkaban, the boggarts are easily one of the coolest ideas to show up in the Potter series. They're all-purpose monsters from your childhood nightmares, formless creatures that take the shape of what you're most afraid of, hiding under the bed or in the closet. It's a great way of taking an idea so familiar to its younger audience and making it a part of the magical world.

Honestly, "boggart" is as good a name as any since its modern usage, like "boogeyman," is a generic term for any malevolent spirit causing trouble around the house. Historically, though, a boggart was a specific creature from British mythology. According to 1851's Dialect and Folk-lore of Northamptonshire, one boggart was described as "a squat hairy man, strong as a six-year-old horse, and with arms almost as long as tacklepoles." That's a pretty definitive shape, but maybe the person doing the describing was just really afraid of Waluigi. And really, who isn't?

House elves are mythical beings that want their freedom

If you're mostly familiar with elves as Santa's singing, toymaking helpers or Tolkien's beautiful, immortals, here's something that might blow your mind. From a folkloric standpoint, J.K. Rowling's elves might actually be the most accurate additions to the wizarding world.

Rowling's elves are direct descendants from Die Wichtelmänner, one of the famous fairy tales collected in the 1800s, which is probably better known to English-speaking audiences as The Elves and the Shoemaker. It's a familiar story, but in case you don't know it, it's about a poor shoemaker who's down to his last scrap of cash who's helped by a pair of elves who cheerfully craft a fine pair of shoes that save his business. They continue to work for him for a while until, flush with cash, the shoemaker and his wife buy the elves some fine sets of miniature clothing, leaving them out as a thank you present. The elves get the clothes, and they stop making shoes because they finally have something of their own.

So yeah, in the original story, the elves are just straight-up buck naked the entire time, which is often left out for the obvious reason that nobody wants to read a story to or make a fanciful cartoon for children about two elves who are just hangin' their broomstick and bludgers out while doing some leather-working. Needless to say, Rowling left that bit out too, dressing her unclothed elves in tea towels and pillowcases. The other big difference? In the original story, the elves are happy to be freed, and they're never depicted as being extremely stoked about remaining as what are essentially slaves.

The Harry Potter series should leave skin-walkers alone

Referring to skin-walkers as "mythical beings" isn't really accurate, for the same reason that referring to, say, Jesus of Nazareth as a "mythical being" wouldn't be accurate, either. After all, skin-walkers are a part of an existing, active belief system. And in this case, they're a part of the Navajo belief system, which isn't well-understood by outsiders. Especially, it turns out, by J.K. Rowling.

In 2016, Rowling expanded her wizarding world to North America through projects like Pottermore that dove into the bits of Harry's world that weren't really covered in the books. There were plenty of things that didn't really make sense in there. For example, there's one wizarding school for the entire United States, which has five times the population of Great Britain and is made up of several distinct regions that, historically, haven't always gotten along or even been part of the same country? Okay, sure. But the most problematic by far was her treatment of Native traditions. In a section on North American magic from the 14th to 17th centuries, Rowling wrote that skin-walkers didn't exist, and they were just lies spread around to discredit wizards. Yikes, Jo.

Unsurprisingly, there was an immediate push back against this from Native writers. They criticized the skin-walker section as an extremely appropriative dismissal of a real-world belief held by actual people, and they also took aim at Rowling's tactic of lumping all of the indigenous cultures of North America into a single, easily dismissed whole. It wasn't a great look to begin with, but the fact that this was one of the few things that was classified as being made-up nonsense in a world where goblins, elves, magic wands, and plenty of other pieces of European folklore were enshrined as canon made it especially rough.